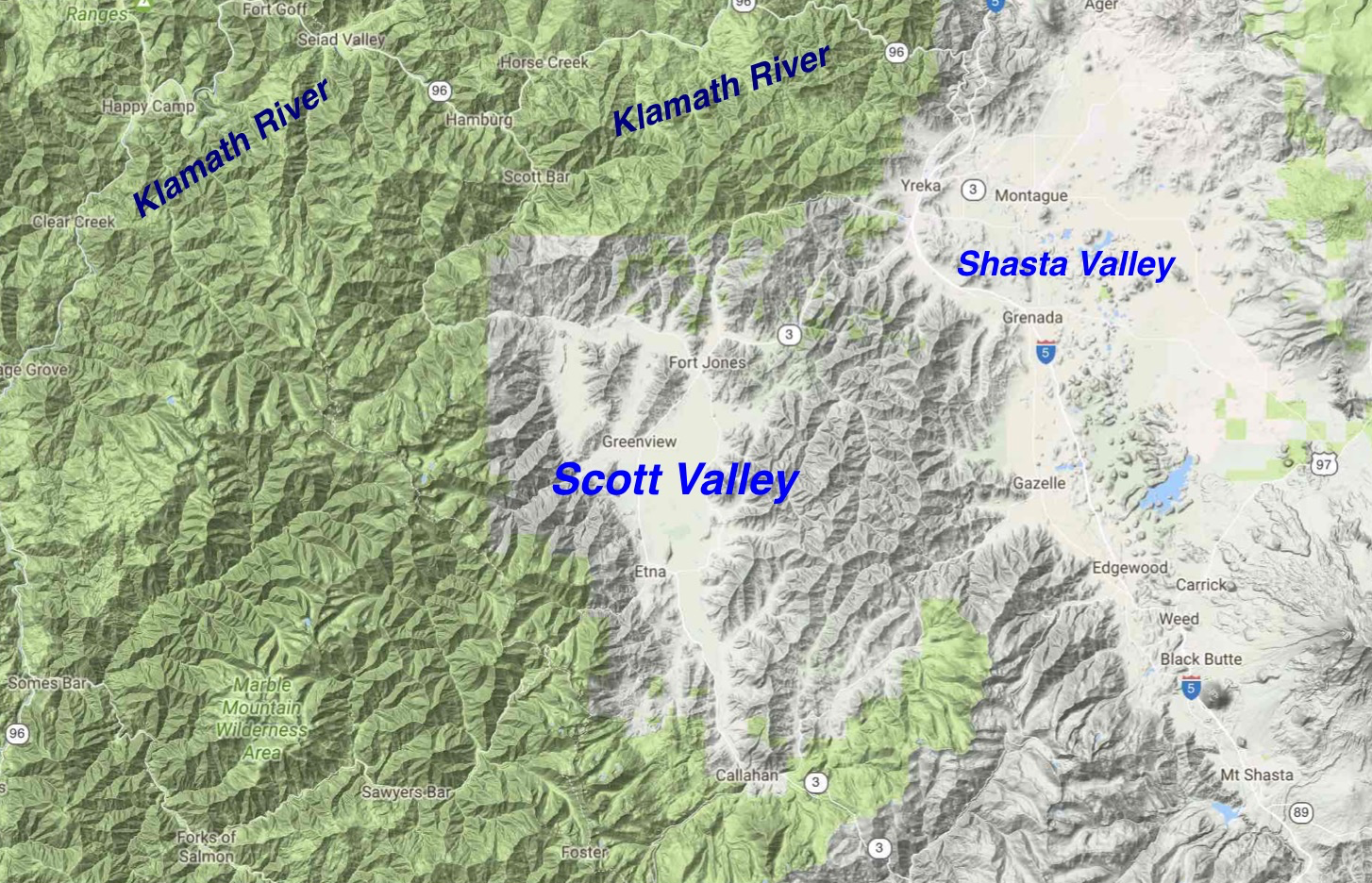

On July 1, 2021, staff from the State Water Resources Control Board (State Board) held a public Zoom meeting to provide information and solicit input on potential actions that could be implemented to address low flows in the Scott River and Shasta River watersheds (Figure 1) during the ongoing drought. The Scott and Shasta rivers are major salmon and steelhead producing tributaries of the Klamath River. The State Board’s July 1 workshop sought input and options prior to taking action.

CSPA is providing comments through this three-part series. Part 1 was the introduction with a description of the general problems and solutions. Part 2 provided specific comments on the Scott River. This is Part 3 on the Shasta River.

The Shasta River Problem

The Shasta River, like the Scott River, has a chronic streamflow problem that occurs in summer and fall of most years. Only in very wet years, do flows sustain the needs of ranchers and fish for water. In most dry years, nearly all the water in the watershed goes to agriculture, while the lower river and most major tributaries run virtually dry (Parks Creek, Little Shasta River, Yreka Creek). Salmon and steelhead survive during dry years only in the middle reaches of the mainstem Shasta River and in adjoining large springs fed by Mt. Shasta’s snow fields or leakage from Lake Shastina reservoir.

At the locations in the watershed that are watered by springs, large portions of the spring-fed flow are diverted for agriculture or other human use (e.g., bottled water, domestic use, cities, etc.). Pasture irrigation, hay production, and stock watering are the major uses. Much of the upper mainstem’s water supply (both spring-fed and snowmelt) is stored in Lake Shastina and metered out over the summer for downstream use through a large canal and ditch irrigation system. Big Springs, the dominant source of spring water to the middle and lower river, is diverted or pumped to irrigation ditch systems from several small diversion dams and multiple small distribution systems.

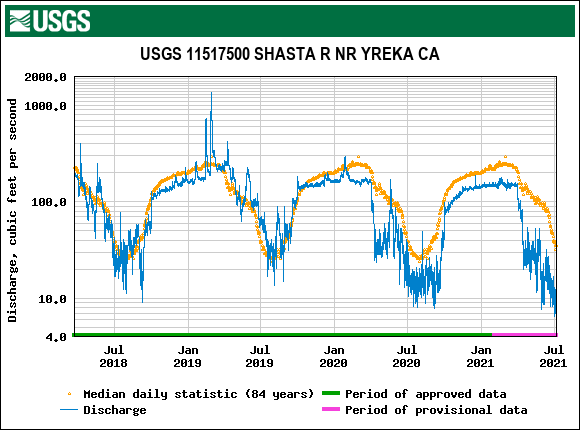

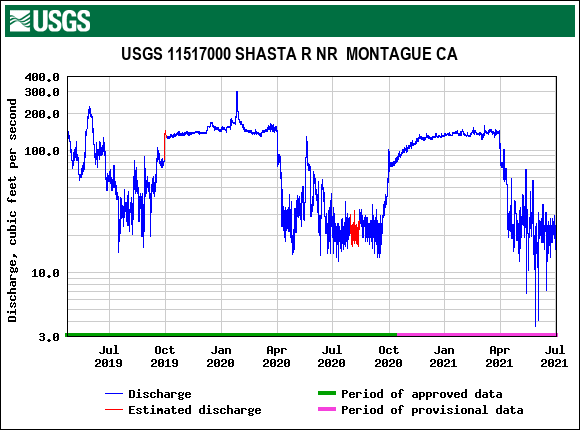

Most salmon and steelhead spawning and rearing occurs in the middle reaches of the river below Lake Shastina and in the reach near Big Springs, where spring-fed cold-water provides high quality spawning and rearing habitat. The inputs of spring water in summer of drier years like 2021 are virtually gone by the time river water reaches Yreka (Figure 2) from the above mentioned extraction systems. The base flow of approximately 150 cfs before the April 1 start of the irrigation season falls to 10-20 cfs or lower by summer. Flow recovers after the irrigation season ends on October 1. Most of the irrigation diversions in the mainstem Shasta River are located in the 10-20 miles downstream of the inflow from Big Springs, as is evident by at the streamflow gage near Montague (Figure 3).

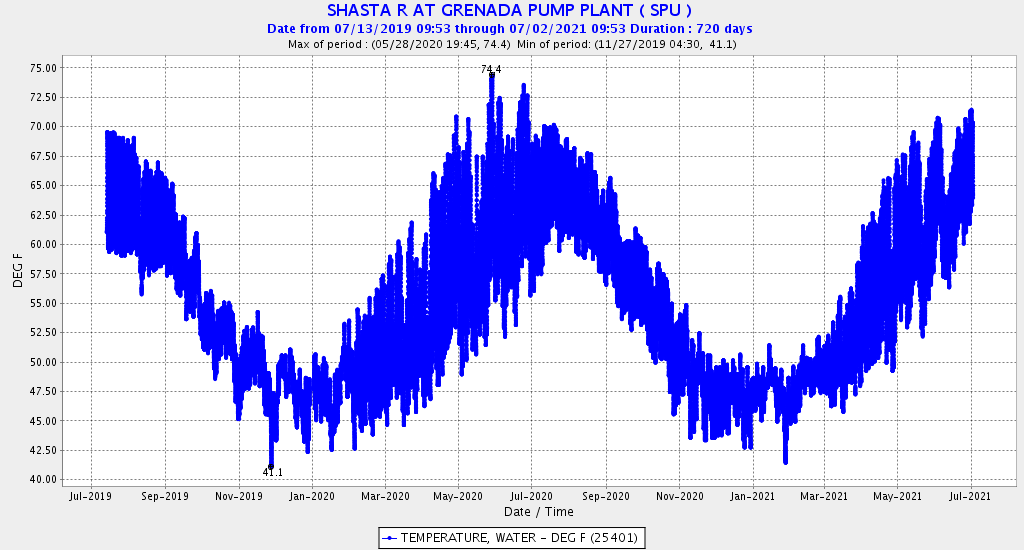

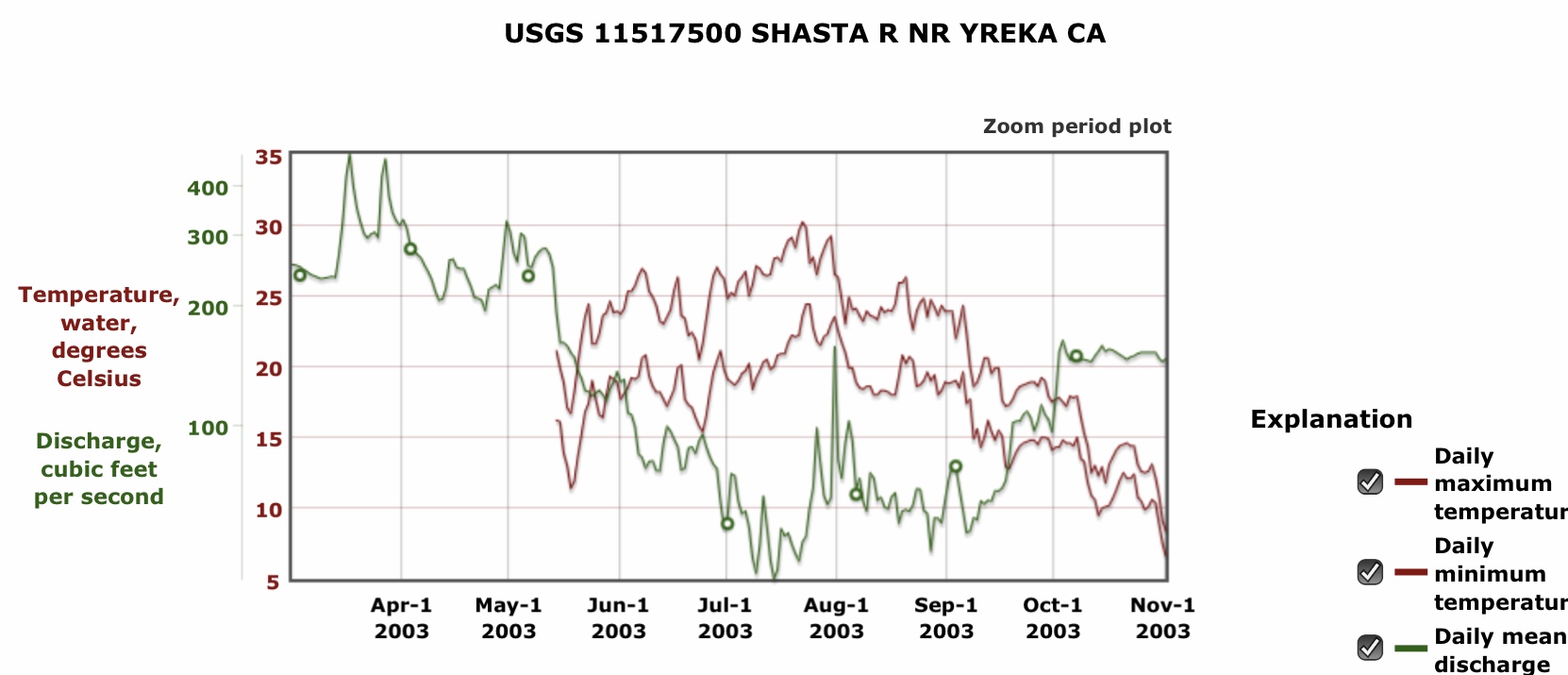

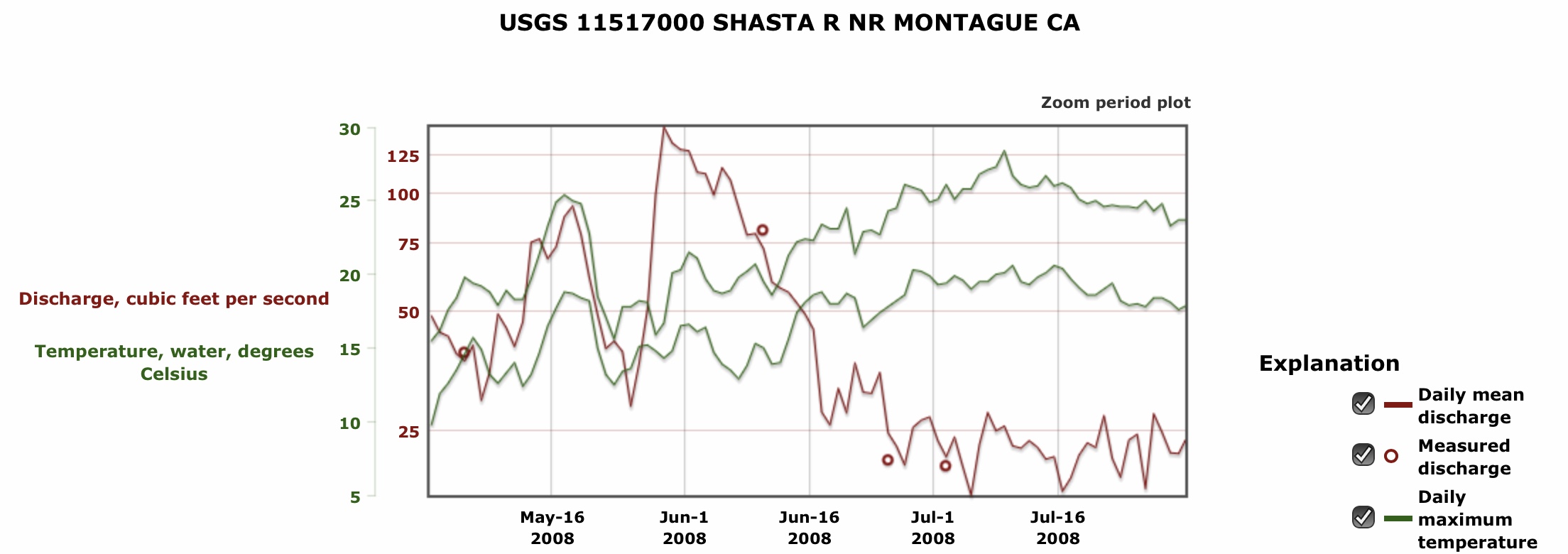

Lower flows lead to high water temperatures in the lower river (>65ºF, Figure 4) that limit fish habitat, survival, and smolt production. Unlike the Scott River, dewatering and stranding are not a primary factor in the middle river’s spring-fed refuge. Rather, the problem is high water temperature between Grenada and the Shasta River’s mouth at the Klamath River. Historical water temperature records at the Yreka gage (Figure 5) indicate that the lower river is virtually uninhabitable in summer with water temperatures 20-25ºC because of low streamflows. Historical data from the Montague gage indicate tolerable water temperatures (<20ºC) when streamflows are >50 cfs (Figure 6). Such flows and water temperatures would at least provide minimum requirements for migrating adult fall run Chinook salmon in late summer.

Solution Option for the Shasta River

CDFW’s recommended minimum instream flows of 50 cfs (about a third of the base flow) is a reasonable measure that would maintain a modicum of over-summer rearing habitat in the spring-fed middle reach of the Shasta River and provide the opportunity for the late-summer salmon migration. The major objective is to protect the many spring inputs in middle reach of the river, where most over-summer rearing of salmon and steelhead occurs, through summer season. This can be accomplished by cutting back diversions and groundwater pumping in the Big Springs area, and by minimizing warm, polluted irrigation return water.

Figure 1. The Scott River and Shasta River Valleys in northern California west of Yreka, CA (Yreka is located in the Shasta River Valley). The Scott and Shasta Rivers flow north into the Klamath River, which runs west to the ocean. The Salmon River watershed is immediately west of the Scott River watershed. The upper Trinity River watershed is immediately to the south of the Scott River watershed.

Figure 2. Shasta River daily-average streamflows at Yreka gage 2018-2021 and historical average. Note very low flows in April 1 to October 1 irrigation season in 2020 and 2021. Base flow from large springs is approximately 150 cfs. Lower flows are from surface and groundwater extraction.

Figure 3. Streamflow in Shasta River at Montague gage 2019-2021. Note distinct reductions in April 1 to October 1 permitted irrigation season.

Figure 4. Water temperature of Shasta River at Grenada 2019-2021. Note water temperature increase at beginning of irrigation season on April 1 and decrease at end near October 1.

Figure 5. Streamflow and water temperature (min-max) of Shasta River near Yreka CA, March-October 2003.

Figure 6. Streamflow and water temperature (min-max) of Shasta River near Montague CA, May-July 2008.