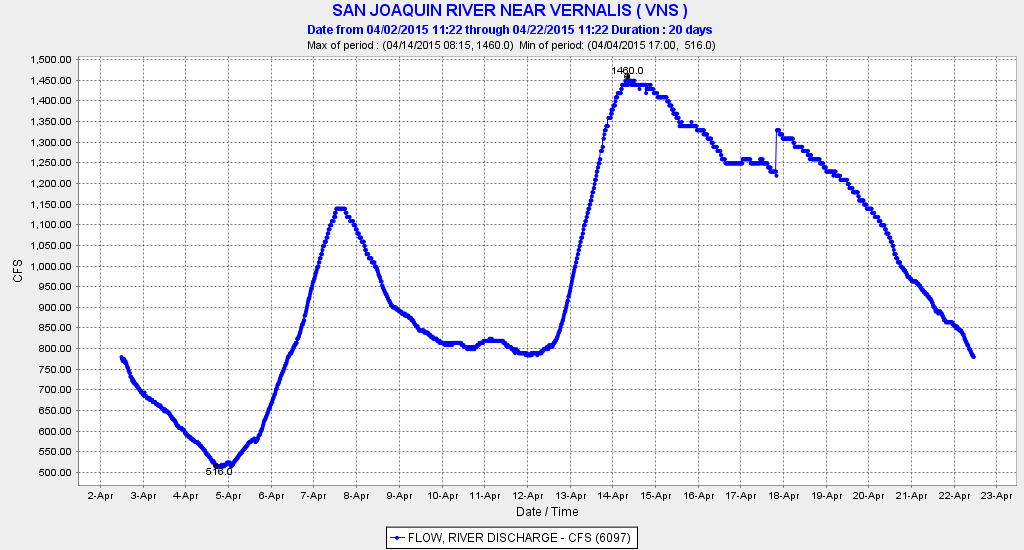

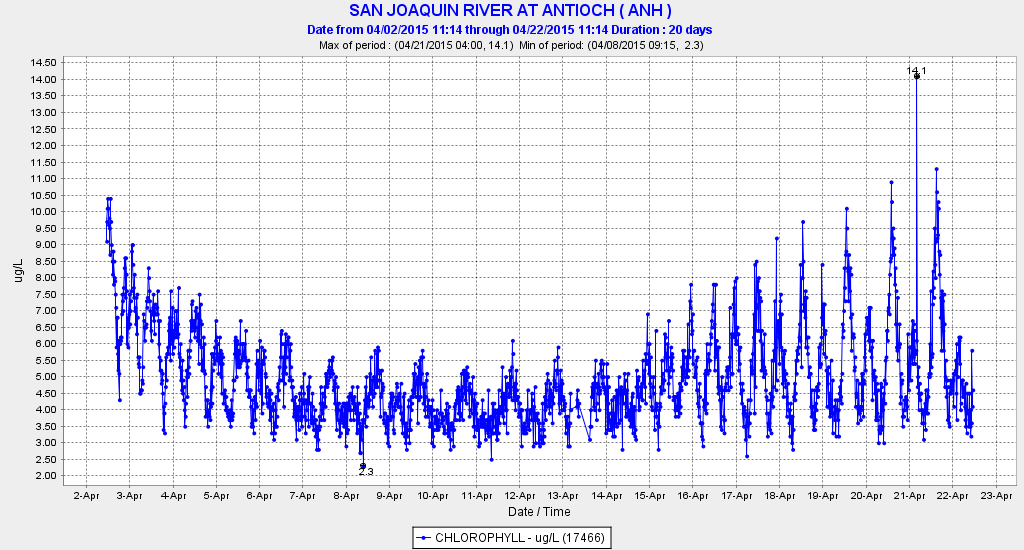

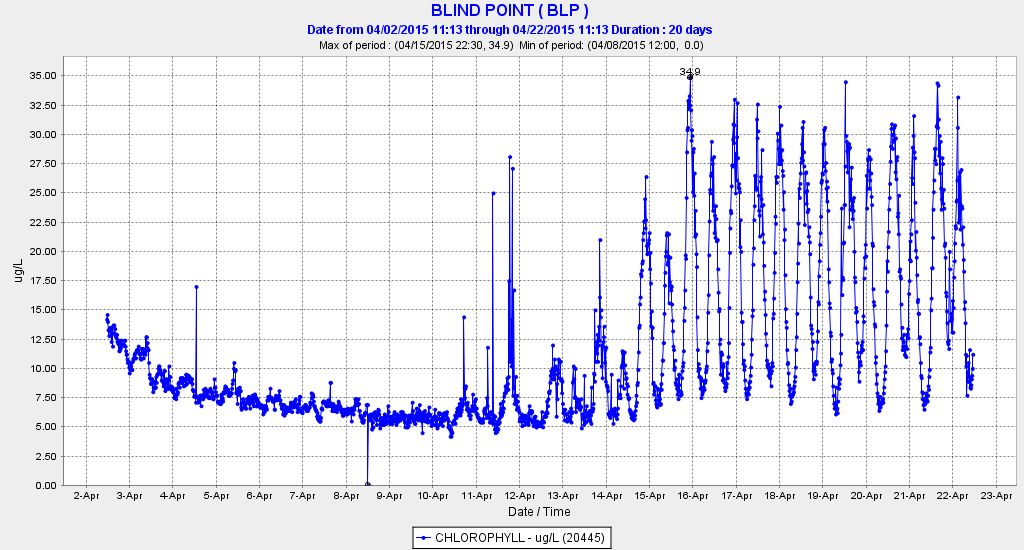

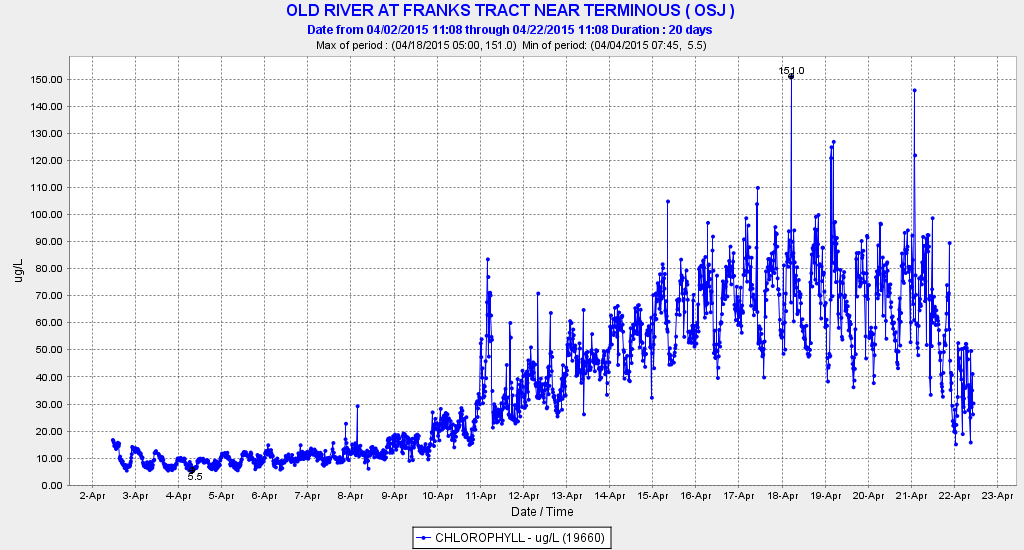

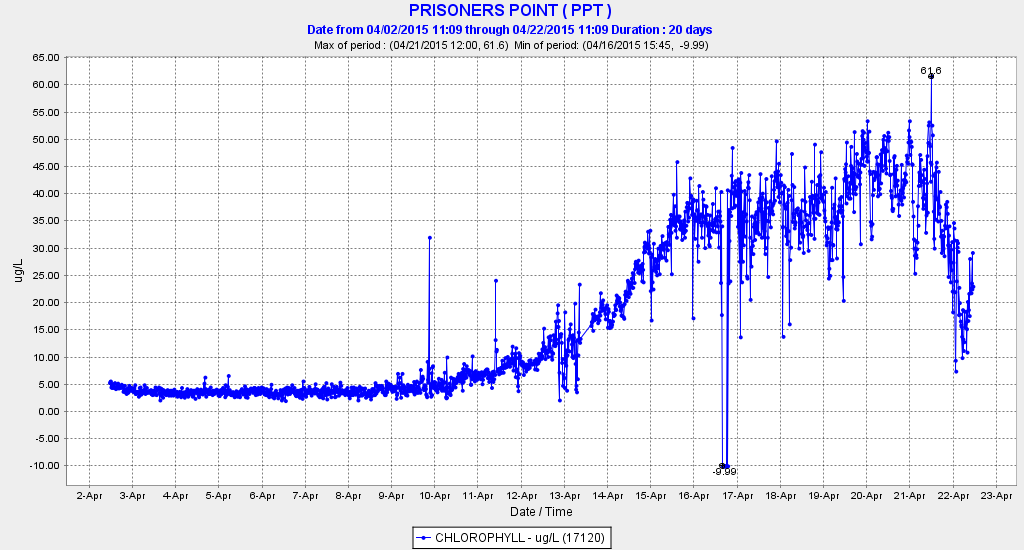

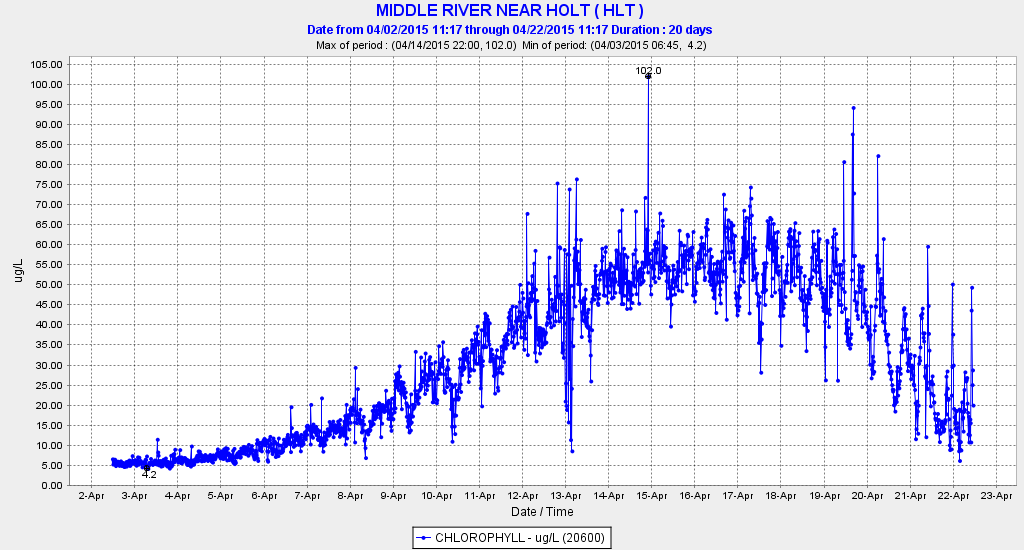

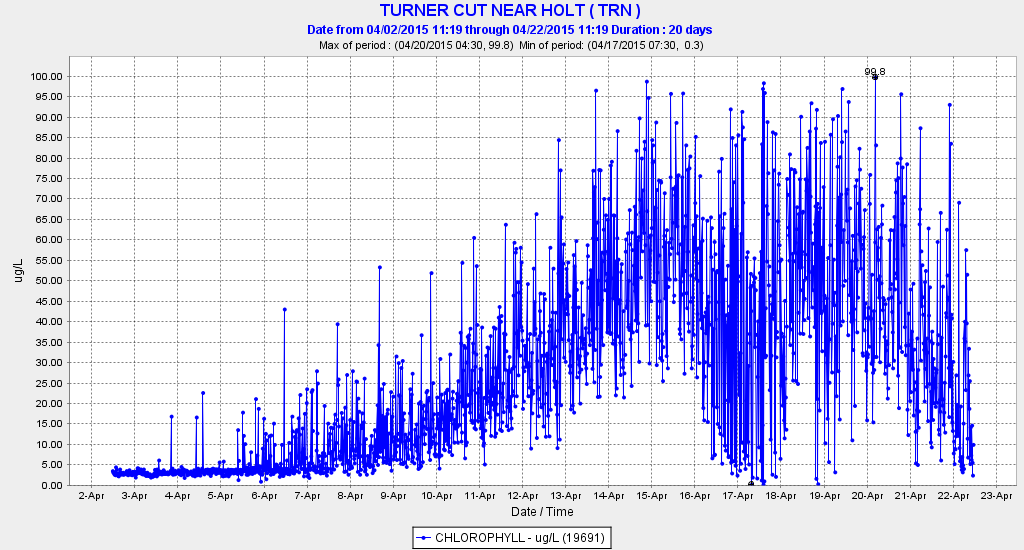

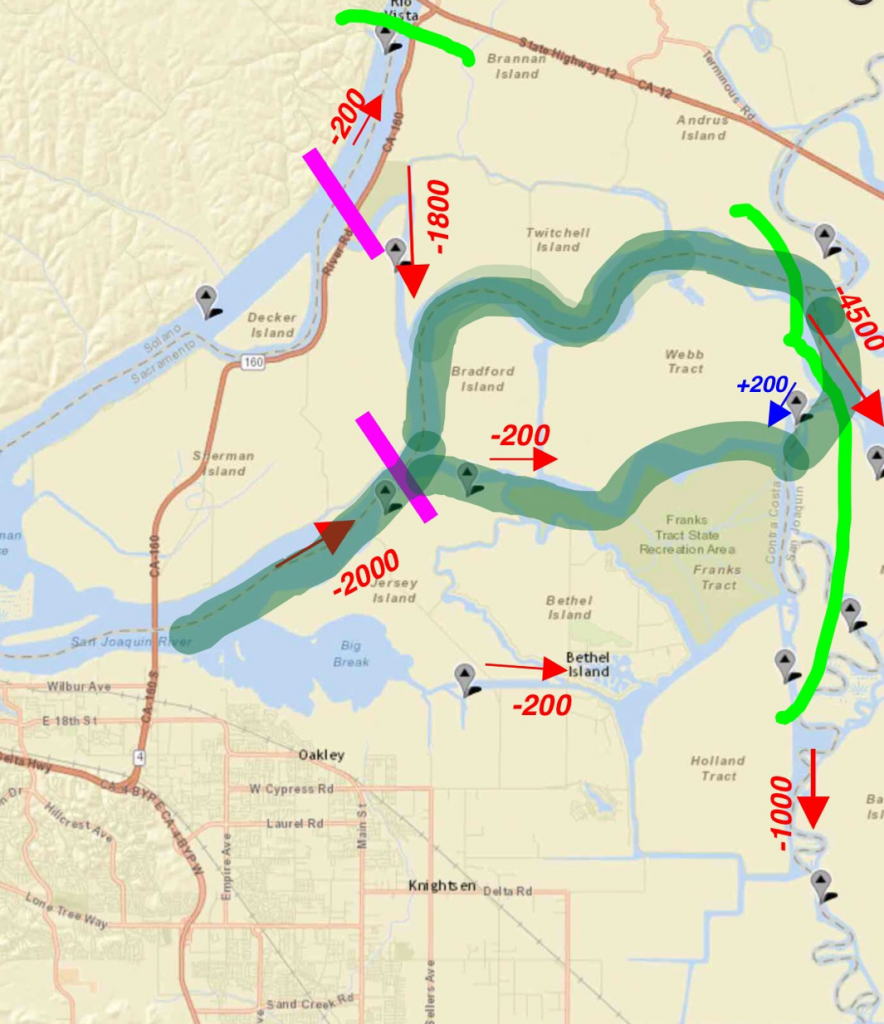

A San Joaquin River pulse flow and low Delta exports in April have led to a plankton bloom in the Central Delta. The pulse flow (Figure 1) and low exports (1500 cfs) were the result of two drought-related actions of the State Water Resources Control Board in its April 6, 2015 Temporary Urgency Change Order. The bloom is a consequence of low net transport flows in central Delta channels toward the south Delta export pumps and of the water habitat thus being allowed to “stew” with nutrients from the San Joaquin River. Chlorophyll levels rose with the onset of the pulse flow and recently have begun to decline with the end of the pulse flow (Figures 4-10). Chlorophyll levels were much lower in the west, north, east, and south parts of the Delta and in Suisun Bay, when compared to the central Delta. This process was described by Arthur and Ball (1977)1

“During spring through fall, export pumping from the southern Delta caused a net flow reversal in the lower San Joaquin River, drawing Sacramento River water across the central Delta to the export pumps. The relatively deep channels and short water residence time apparently resulted in the chlorophyll concentrations remaining low from the northern Delta and in the cross-Delta flow to the pumps.”

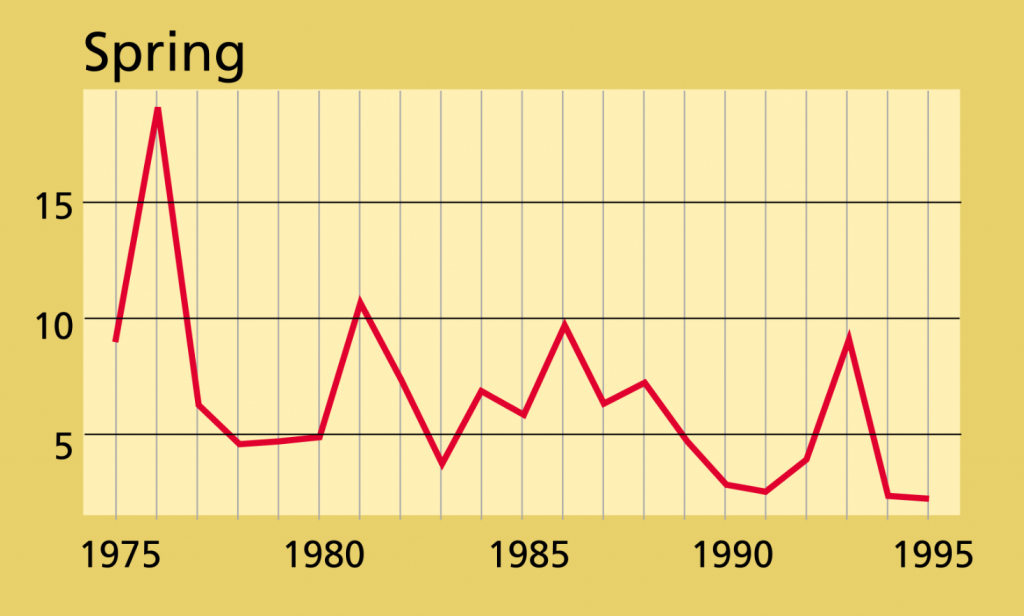

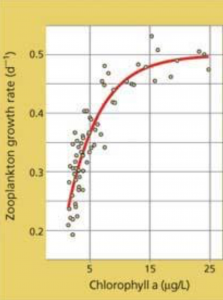

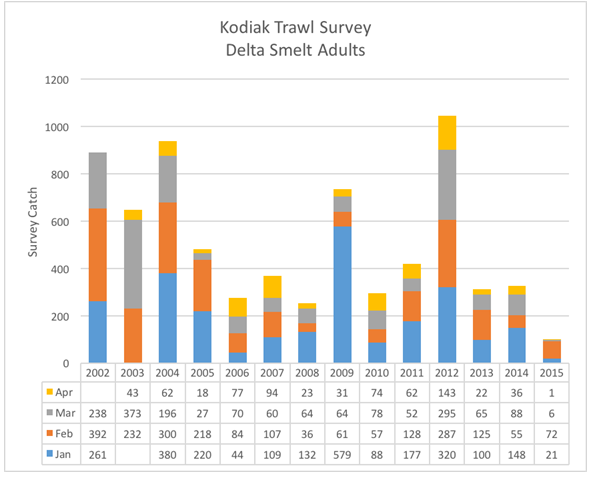

Such a spring bloom is important because it stimulates Delta productivity that is key to native Delta fish survival and production. Lack of Delta productivity over the past several decades (Figure 2) has been related to the Pelagic Organism Decline and near extinction of Delta Smelt (Jassby et al 2003)2. Low chlorophyll levels are also related to poor zooplankton growth rates (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Spring Delta chlorophyll levels below 10 micrograms per liter are considered low primary productivity. (Source: Jassby et al. 2003)

Figure 3. Zooplankton growth rates peak above chlorophyll levels above 10 micrograms per liter. (Source: Jassby et al. 2003)

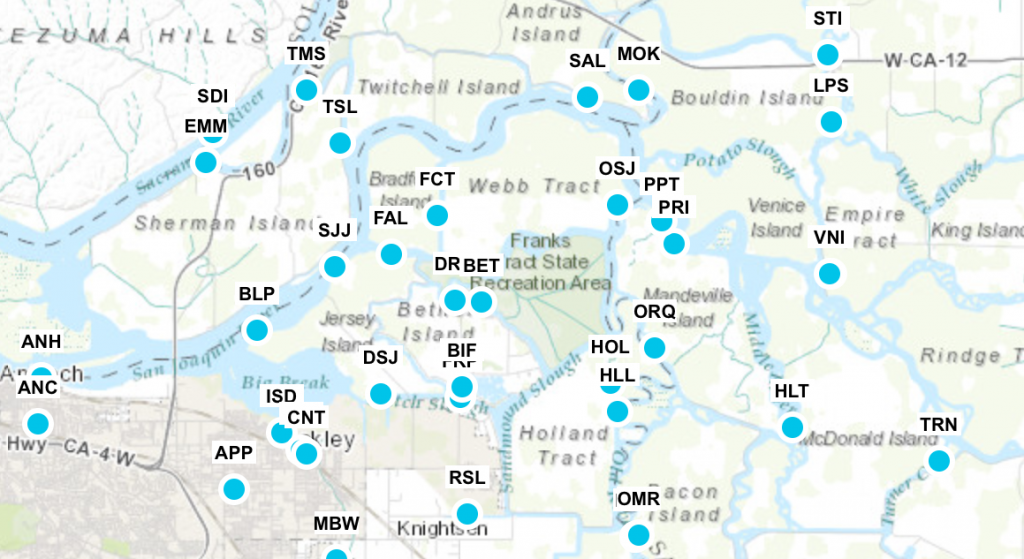

Figure 4. The six stations with chlorophyll data presented in the following charts from west to east are:

• ANH – Antioch

• BLP – Blind Point

• OSJ – Old River at Franks Tract

• PPT – San Joaquin River at Prisoners Point

• HLT – Middle River at Holt

• TRN – Turner Cut

- Arthur, J, and M. Ball. 1977. Planktonic Chlorophyll Dynamics in the Northern San Francisco Bay and Delta. Fifty-eighth Annual Meeting of the Pacific Division of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, June 12-16, 1977. http://downloads.ice.ucdavis.edu/sfestuary/conomos_1979/archive1029.PDF ↩

- Jassby, A., J. Cloern, and A. Muller-Solger. 2003. Phytoplankton fuels Delta food web. California Agriculture 57(4): 104-109. ↩

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.

The small numbers of Steelhead I have caught or seen caught, or observed while snorkeling, are most often hatchery fish, likely strays originating from the Feather River Hatchery. In fact, a small percentage of the resident trout above and below Daguerre are hatchery steelhead that did not migrate to the ocean (photo at right). Hatchery smolts released in the lower Feather River near the mouth of the Yuba often move up the Yuba.