Delta outflow is the amount of fresh water that exits the Delta for San Francisco Bay. Freshwater outflow is the most important ecological function other than perhaps the tides for the Bay-Delta Estuary. The Net Delta Outflow Index (NDOI) is the parameter that is used as a measure of Delta outflow to manage the ecology, water supply, and water quality of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Estuary. NDOI is a number estimated from a crude set of variables, some measured and some guessed. It is a relic of the past and deserves a quiet burial, the sooner the better. Continuing its use is meaningless, unreasonable, harmful, injurious, and unnecessary.

The NDOI or QOUT is calculated as follows:

QOUT = QTOT + QPREC – QGCD – QEXPORTS – QMISDV1

Where:

- QOUT Net Delta outflow at Chipps Island

- QTOT Total Delta inflow

- QPREC Delta precipitation runoff estimate

- QGCD Delta-wide gross channel depletion estimate (consumptive use)

- QEXPORTS Total Delta exports and diversions/transfers

- QMISDV flooded island and island Storage diversion

All of these parameters are estimates themselves subject to gross errors, which compound to make NDOI useful only as a gross indicator of freshwater outflow to San Francisco Bay.

The main use of NDOI is in Bay-Delta water quality standards and drought emergency change orders:

“ The Delta outflow objectives included in the Bay-Delta Plan and D-1641 for the February through June time frame are identified in footnote 10 of Table 3 and Table 4 of footnote 10. Pursuant to footnote 10, the minimum daily NDOI during February through June is 7,100 cfs calculated as a 3-day running average. This requirement may also be met by achieving either a daily average or 14-day running average EC at the confluence of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers of less than or equal to 2.64 millimhos per centimeter (mmhos/cm) (Collinsville station C2)… The minimum Delta outflow levels specified in Table 3 are modified as follows: the minimum Net Delta outflow Index (NDOI) described in Figure 3 of Decision 1641 during the months of February and March shall be no less than 4,000 cubic-feet per second (cfs) on a monthly average. The 7-day running average shall not be less than 1,000 cfs below the monthly average.”2

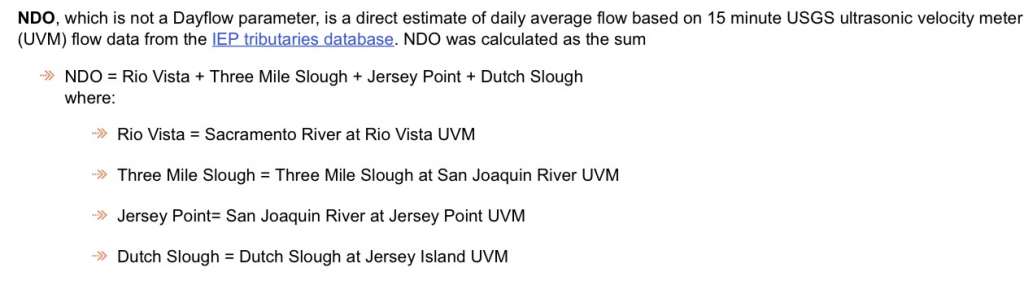

Reliance on NDOI is one thing, but using 3-day, 7-day, and monthly average limits borders on insidious. Government agencies have long recognized this and a decade ago commissioned the US Geological Survey to measure Delta outflow with UVM meters that measure water column velocities in real time.

.

The new measurement is defined as Net Delta Outflow or NDO3.

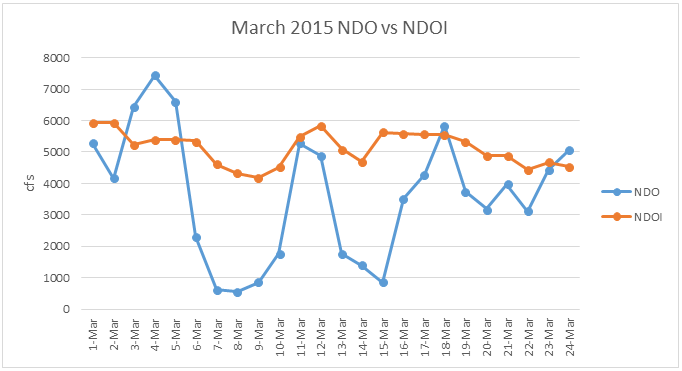

We compared the two parameters for the month of March, 2015. The differences in the parameters as seen in the chart below are significant and appear to be related to the fact that NDOI does not incorporate tidal effects. NDO indicates that outflow is much reduced by high “spring” tides that effectively block freshwater outflow to the Bay. The effect is real and roughly amounts to over 100,000 AF of freshwater flow that did not make it to the Bay in March, which resulted in greater saltwater intrusion and degradation of the Bay-Delta Estuary, as well as degradation of Low Salinity Zone habitat quality and quantity.

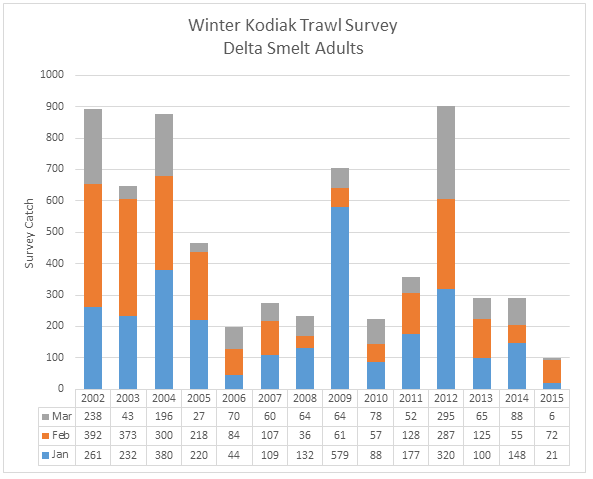

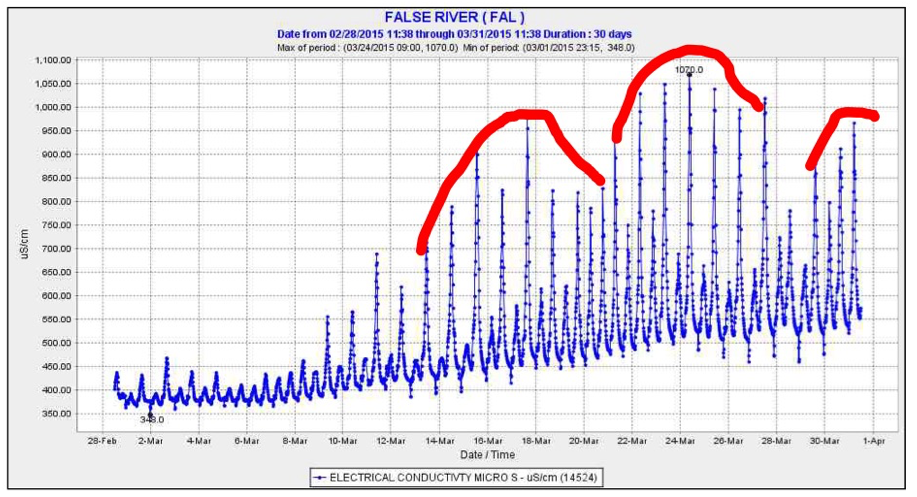

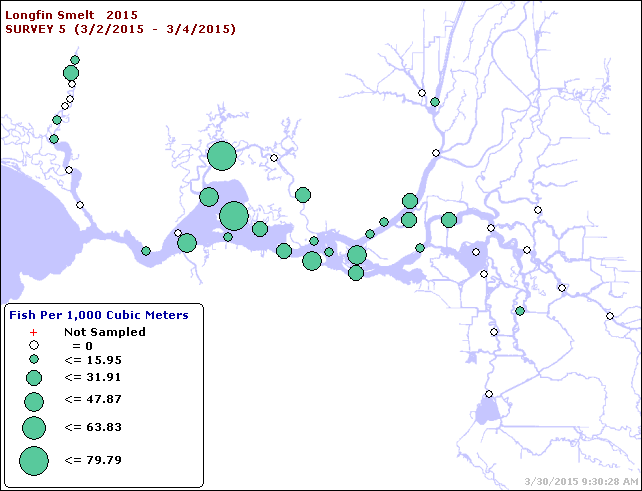

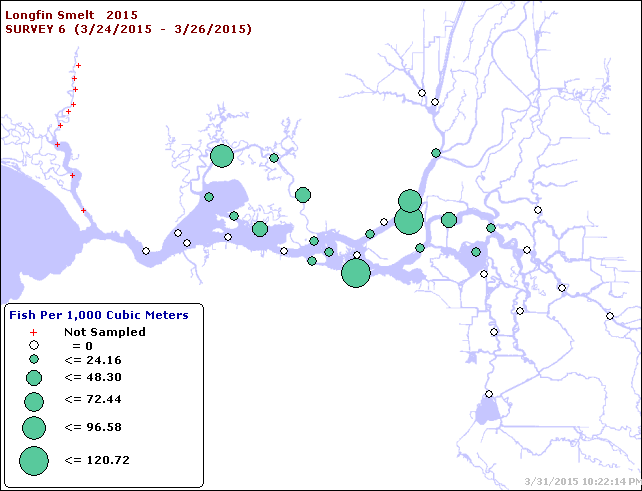

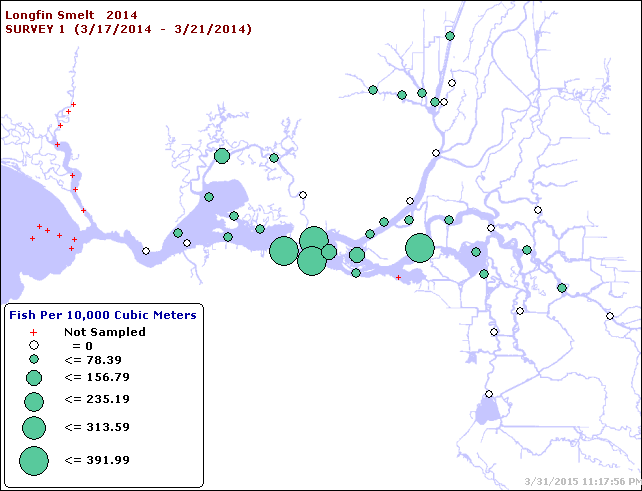

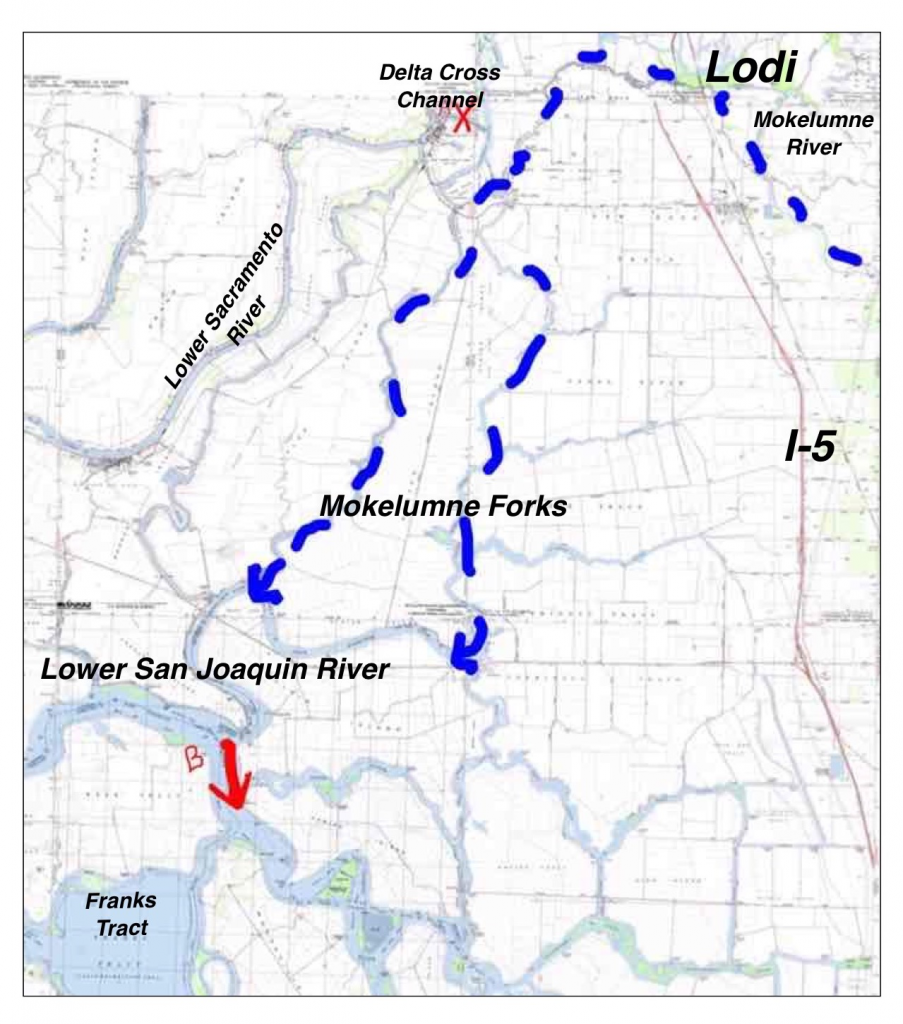

The effect also leads to saltwater intrusion into the central Delta via False River. Delta exports pull some of their water from the west Delta to the south Delta pumping plants via False River. The chart below shows higher salinity water entering False River during high tides with peaks in salinity during spring tides and low NDOs. The salt from these intrusions degrades Delta water quality and the quality of water exported from the Delta to Southern California. The salt is also a signature of the Low Salinity Zone, which is the primary nursery area for Delta Smelt, Longfin Smelt, and many other Delta fish. Pulling LSZ water into the central Delta kills many Longfin and Delta smelt.

It is no longer reasonable to manage Delta outflow and exports with rules that include the NDOI. A vast array of flow, salinity, temperature, turbidity, chlorophyll, dissolved oxygen, and radio-tagged fish detection meters allow instantaneous management of the Delta. Changes are hung up on antiquated Delta standards that are frequently relaxed by the State Water Resources Control Board to satisfy the insatiable water demands of the state and federal water projects and their contractors. The NDOI needs a quick burial. If the Board can issue temporary drought emergency change orders involving the NDOI, why can’t it rely on better measurement to better protect, if only temporarily, the beneficial uses of the state’s water supply?

- Source: http://www.water.ca.gov/dayflow/ndoVsNdoi/ ↩

- Source: SWRCB March 5 Temporary Urgency Change Order for Central Valley Project and State Water Project ↩

- http://www.water.ca.gov/dayflow/ndoVsNdoi/ ↩

The 14-inch “half-pounder” hatchery steelhead in photo at right was caught in the lower American River in early March. It was likely one of 430 thousand stocked last June into the American River as fingerlings when Nimbus hatchery water was predicted to be too warm to sustain the fish through the summer. “Half pounder” is the name given to young steelhead that spend a few months in coastal waters before returning as premature adults to their natal rivers. This fish actually weighed about a pound. This “half-pounder” life history strategy is more frequent in North Coast steelhead, and may reflect the Eel River origin of the American River hatchery stock.

The 14-inch “half-pounder” hatchery steelhead in photo at right was caught in the lower American River in early March. It was likely one of 430 thousand stocked last June into the American River as fingerlings when Nimbus hatchery water was predicted to be too warm to sustain the fish through the summer. “Half pounder” is the name given to young steelhead that spend a few months in coastal waters before returning as premature adults to their natal rivers. This fish actually weighed about a pound. This “half-pounder” life history strategy is more frequent in North Coast steelhead, and may reflect the Eel River origin of the American River hatchery stock. ung steelhead.The native American River steelhead are “spring” run like the many larger fresh (bright) adults I have caught over the past two decades in the river from March-June. The bright steelhead at left was caught in June. Whether a remnant run or some genetic material remains in the population from these fish is unknown.

ung steelhead.The native American River steelhead are “spring” run like the many larger fresh (bright) adults I have caught over the past two decades in the river from March-June. The bright steelhead at left was caught in June. Whether a remnant run or some genetic material remains in the population from these fish is unknown. With record low numbers of winter (Dec-Feb) steelhead reaching the hatchery this year

With record low numbers of winter (Dec-Feb) steelhead reaching the hatchery this year