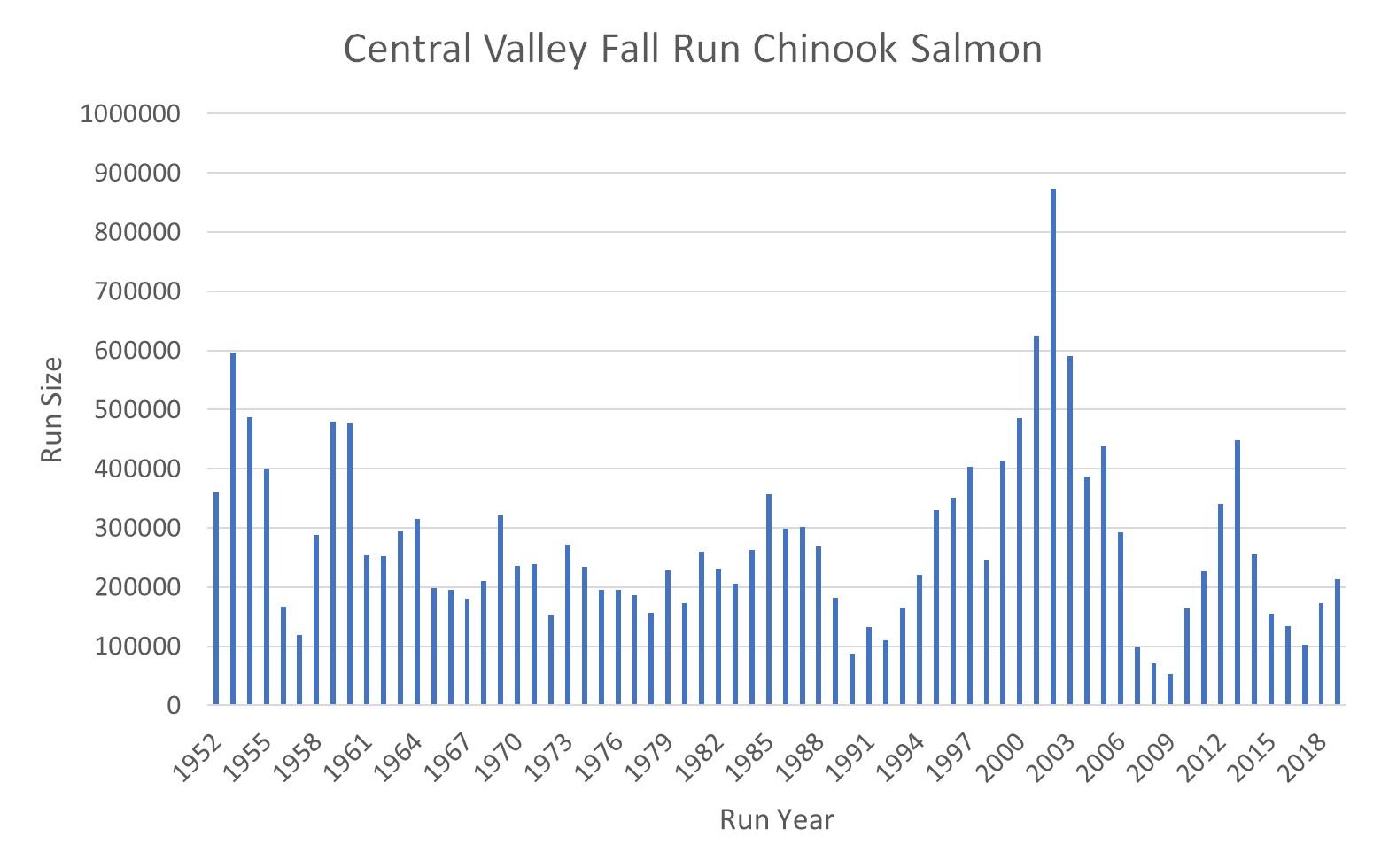

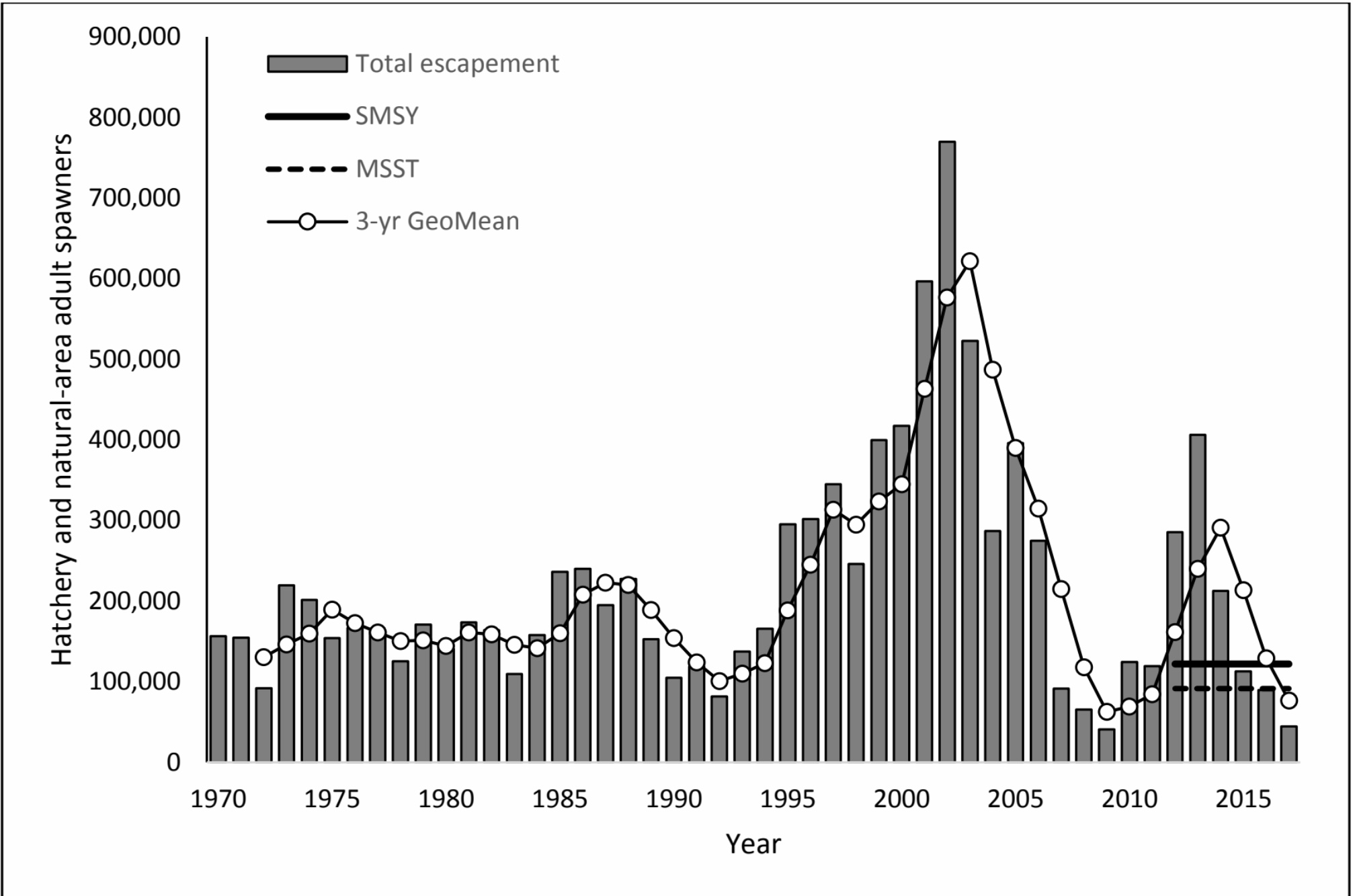

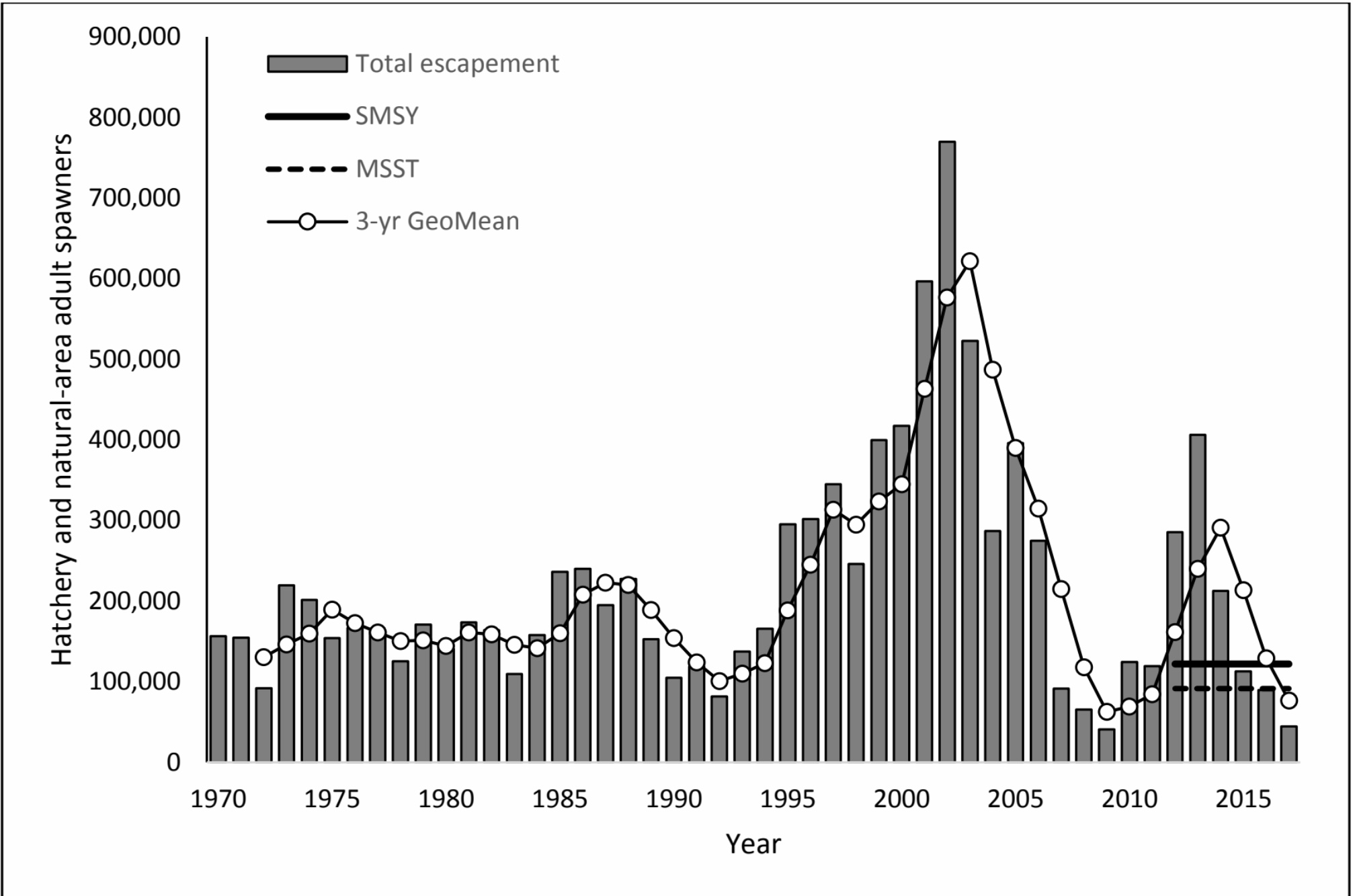

The federal-state Salmon Rebuilding Plan for Sacramento River Fall Chinook (SRFC) (July 2019) was developed by the Pacific Fishery Management Council (PFMC) under a grant from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). The plan was developed because the SRFC escapement (in-river and hatchery return spawners) for brood years 2012-2014 declined significantly after the 2013-2015 drought, as shown in counts of adults that returned in 2015-2017 (Figure 1).

Regrettably, this plan is doomed to failure in periods of drought, because it does not address the underlying problems or long-term solutions that would contribute to meeting goals in the future. As stated in the plan, “the occurrence of reduced stock size or spawner escapements, depending on the magnitude of the short-fall, could signal the beginning of a critical downward trend.” This is the problem any salmon rebuilding plan must correct.

Instead, the plan focuses on three strategies as alternatives: no action, reducing harvest quotas by 30%, and closing regional elements of fisheries (including all inland river fisheries). The plan’s focus on reducing harvest or increasing hatchery production will not address the population crashes during multiyear droughts and limited recovery in subsequent normal and wet years that are the main underlying cause of the population’s decline.

The plan was prepared by the Salmon Technical Team, NMFS, and Council staff with support from state and federal agencies and tribal scientists. The plan is based on an extensive review of all aspects of the issue by many knowledgeable salmon scientists. The goal is to create a consensus plan for how the SRFC stock should be rebuilt so it can sustain a maximum yield harvest strategy within several years.

The plan is designed to meet specific goals and objectives. The goal is to rebuild the SRFC stock so it can provide a Maximum Sustained Yield (MSY) of 122,000 hatchery and natural-area adults to coastal and in-river fisheries. This goal has been in place since 1984. The objective is to reach the goal in two to three years.

The Salmon Rebuilding Plan is not a plan to protect and recover the Evolutionary Significant Unit designated as Central Valley Fall-Run Chinook Salmon and its component subpopulations of wild, naturally produced salmon in the river and its tributaries. Instead, it is a plan to rebuild stocks for harvest and escapement including hatchery and “wild” salmon. The plan’s strategy focuses on adjusting the fishery efforts and harvest to accomplish the PFMC’s goal of rebuilding the fishable stocks, factors the PFMC can control, while mentioning the real problems and other, more long-term solutions in passing.

The plan summarizes the development team’s analyses and conclusions, and suggests multiple factors contributed to the escapement decline of SRFC in years 2015-2017.

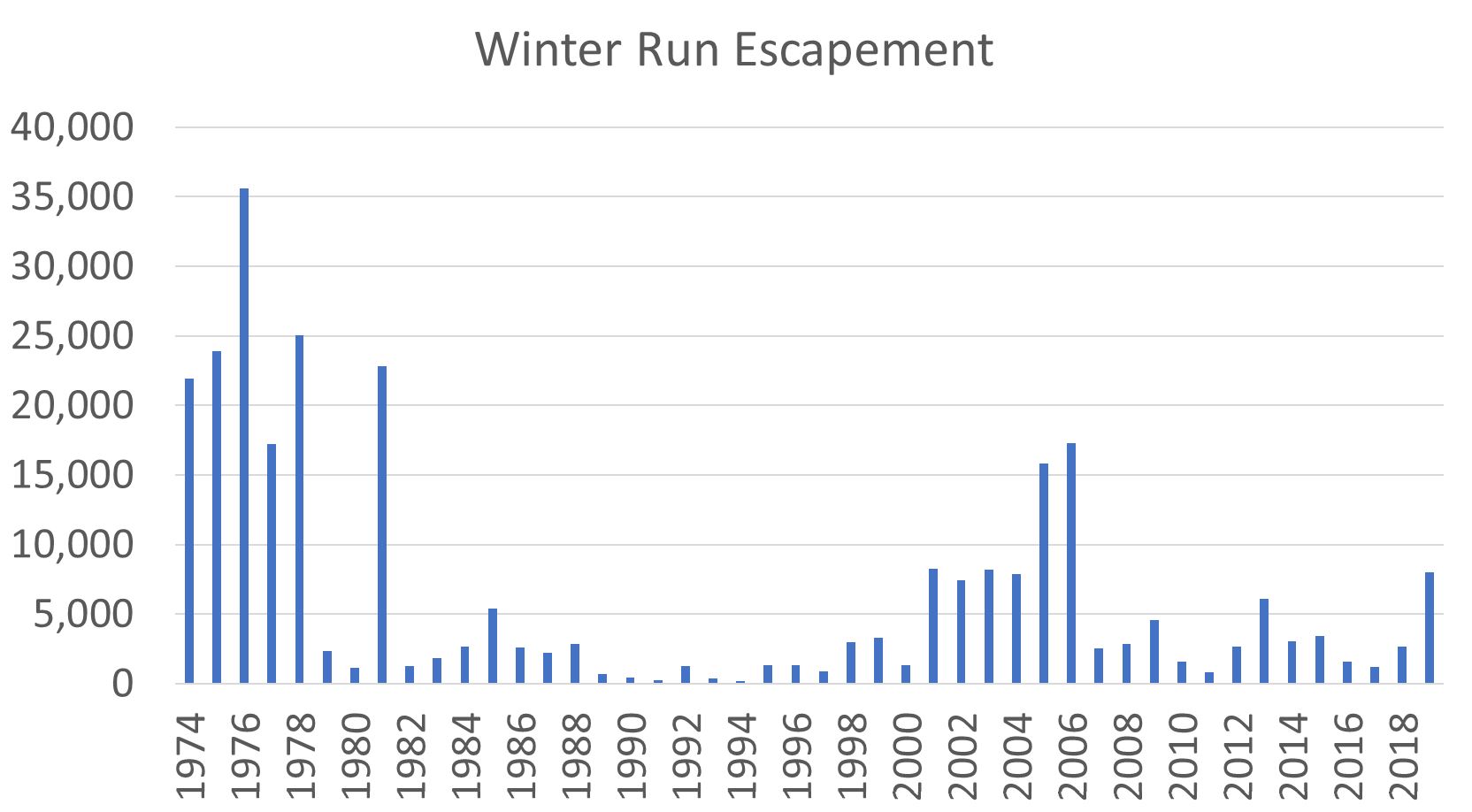

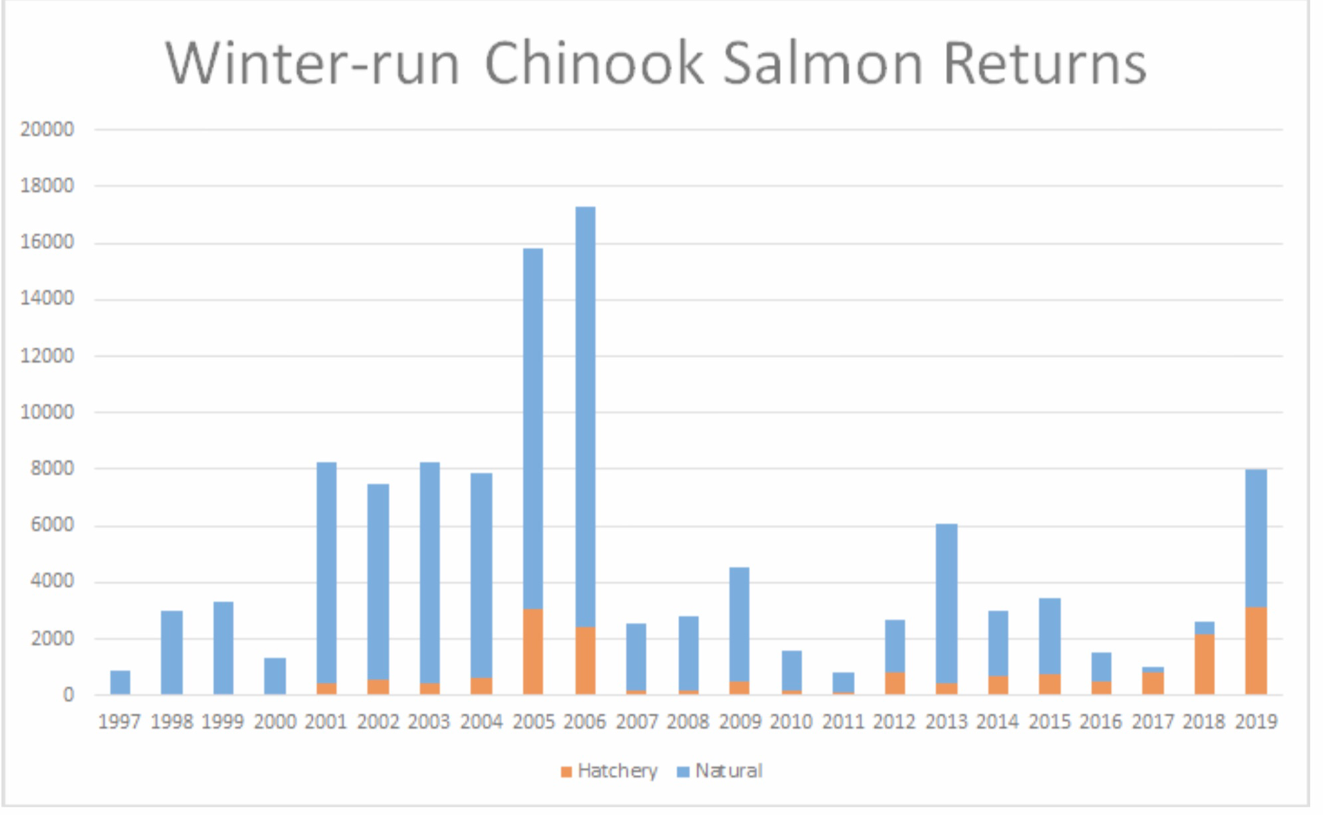

The critical broods of 2012-2014 resulted in well below average ocean abundance index values and adult spawner escapement in 2015-2017. Brood year 2014 appears to be the weakest of the critical broods as it was the primary contributor to the very low 2017 SI postseason estimate and one of the lowest spawner escapement estimates on record. The record low escapement to the upper Sacramento Basin in 2017 is particularly noteworthy. ( p. 60)

Some of the statements in the plan, and my response to each, are shown below. They are organized by topic.

1. Early Life History Survival –

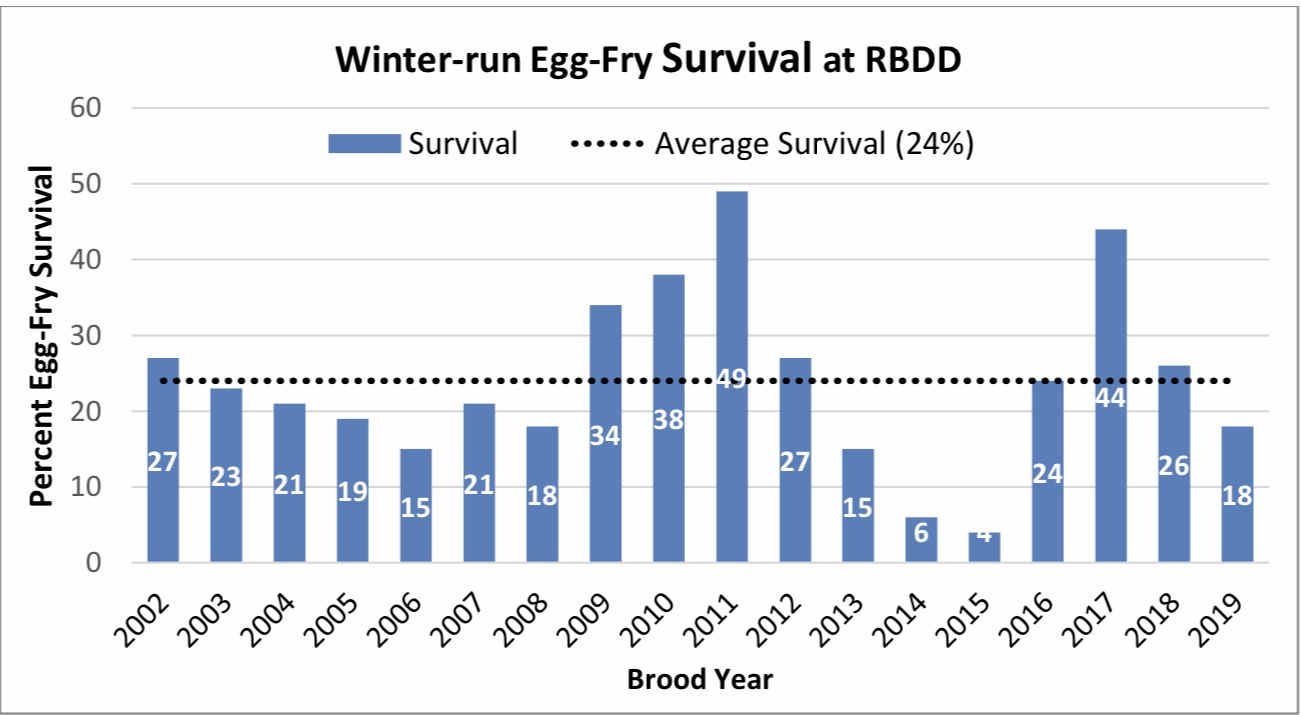

The analysis found that below average freshwater flows and high temperatures throughout the Sacramento Basin coincided with relatively high levels of pre-spawn mortality for the critical broods (defined as brood years 2012-2014). Low flows and warm temperatures in the lower Sacramento River were likely to have affected survival of outmigrating smolts from brood years 2013 and 2014….. The 2013-2015 drought likely impacted juvenile SRFC in several ways resulting in decreased recruitment to ocean fisheries and subsequent adult escapement…. Low flows and elevated water temperatures associated with exceptional drought conditions in the Sacramento River Basin were experienced by outmigrating juvenile SRFC beginning in spring 2013 and these conditions persisted through spring outmigration periods in 2014 and 2015.

Note the plan report relates many of these early life history survival factors that have been identified over the past several decades. There is much documentation of these decades of data and studies in the plan report. Factors such as high water temperatures and redd dewatering have significantly reduced wild smolt production, especially during critical drought years.

2. Lower Hatchery Releases – “Hatchery releases were below average levels for the critical brood years, and offsite release practices utilized during drought conditions led to increased straying and river harvest of returning adults.”

The normal 26.7 million releases were reduced 17% in brood years 2012-14. Note some of these reductions in smolt releases were planned, while others involved difficulties in hatcheries in the critical drought years of 2013-2015.

3. Poor Ocean Survival – “for the critical brood years of 2012-2014, outmigrating juvenile SRFC encountered a wide range of ocean conditions. Poorer conditions in 2014 and 2015 were encountered by brood years 2013 and 2014.”

The primary issue appears to have been that hatchery juveniles released in the Bay generated adult survival, returns and harvest that were orders of magnitude higher than those of hatchery juveniles released in rivers.

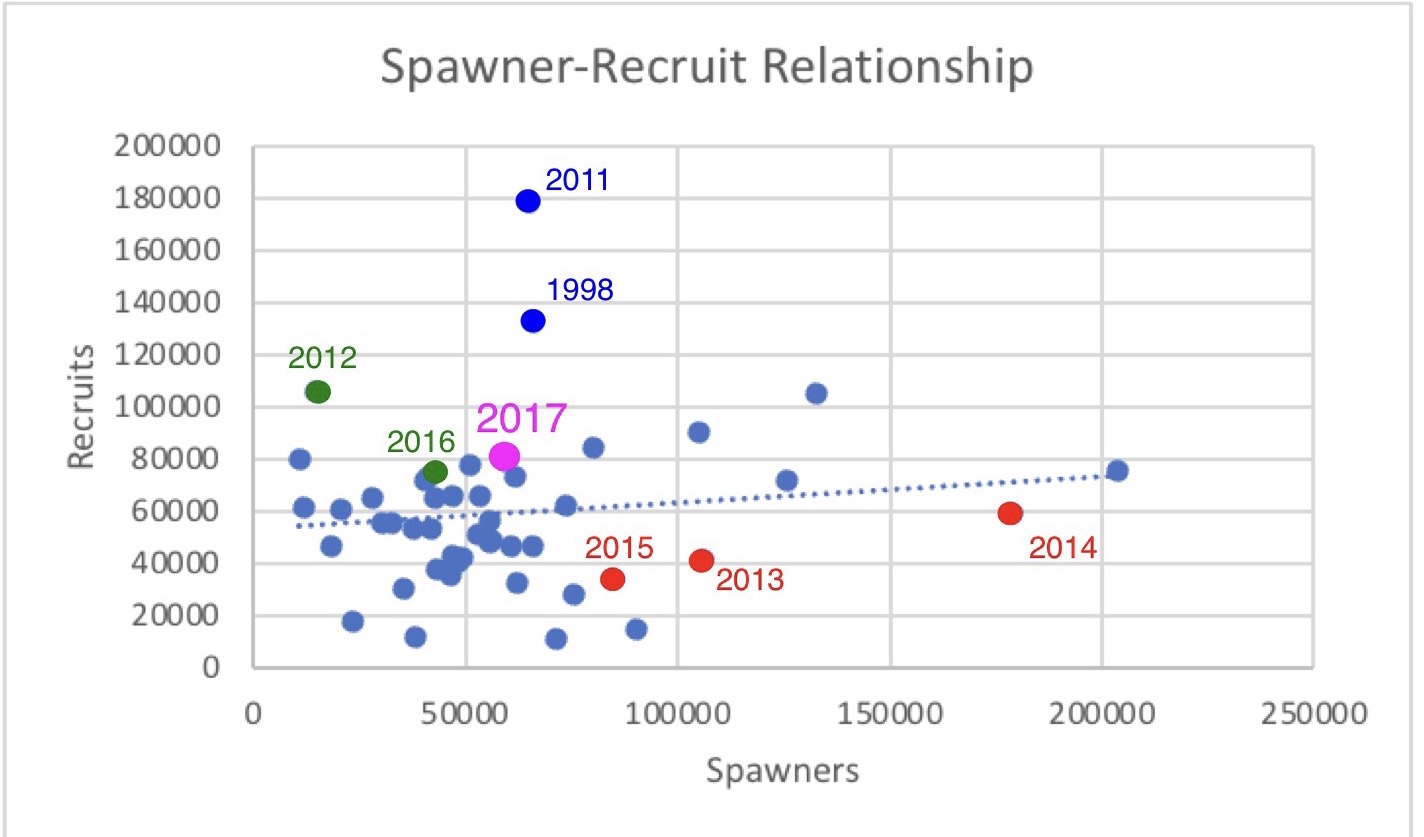

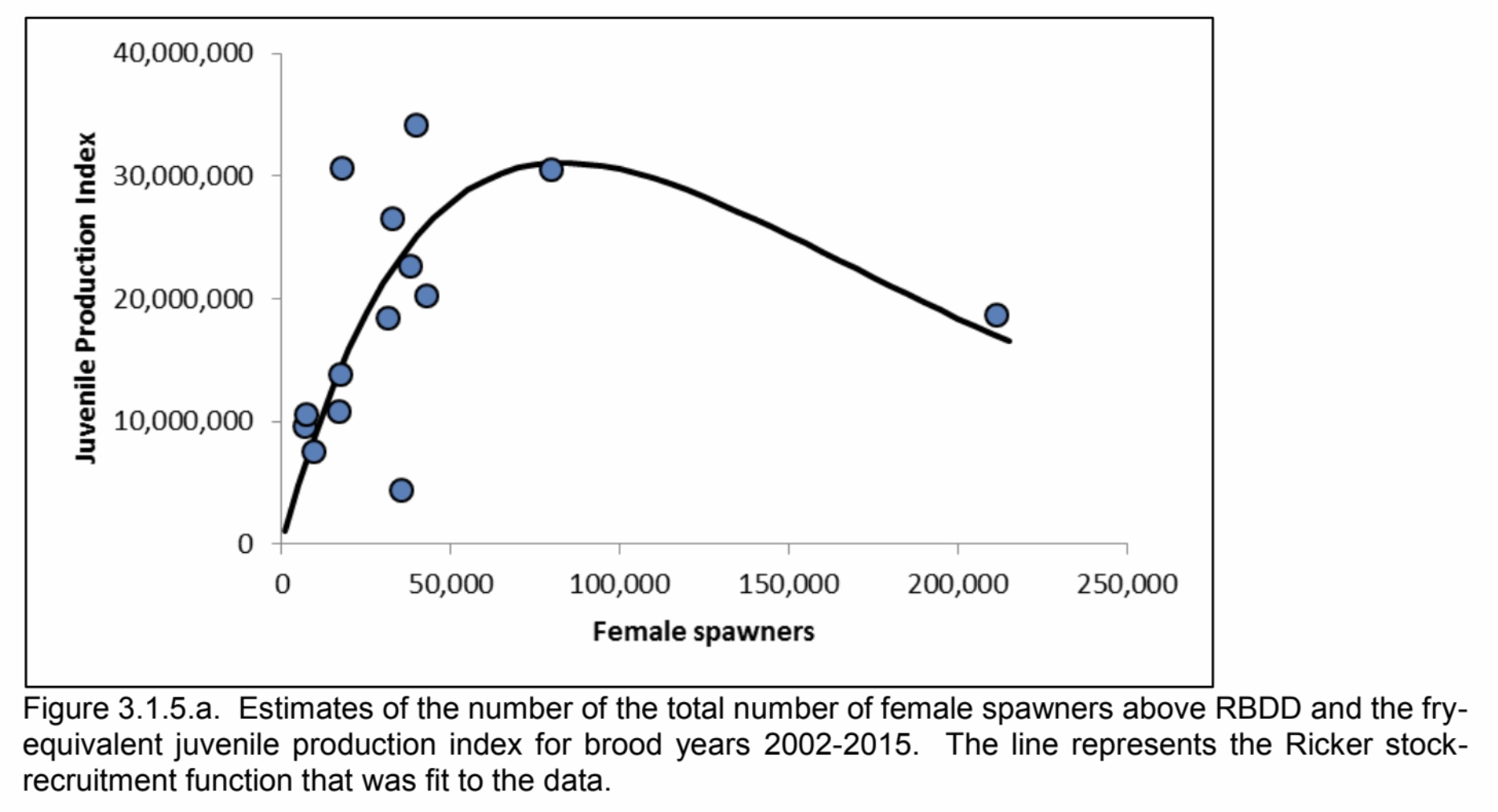

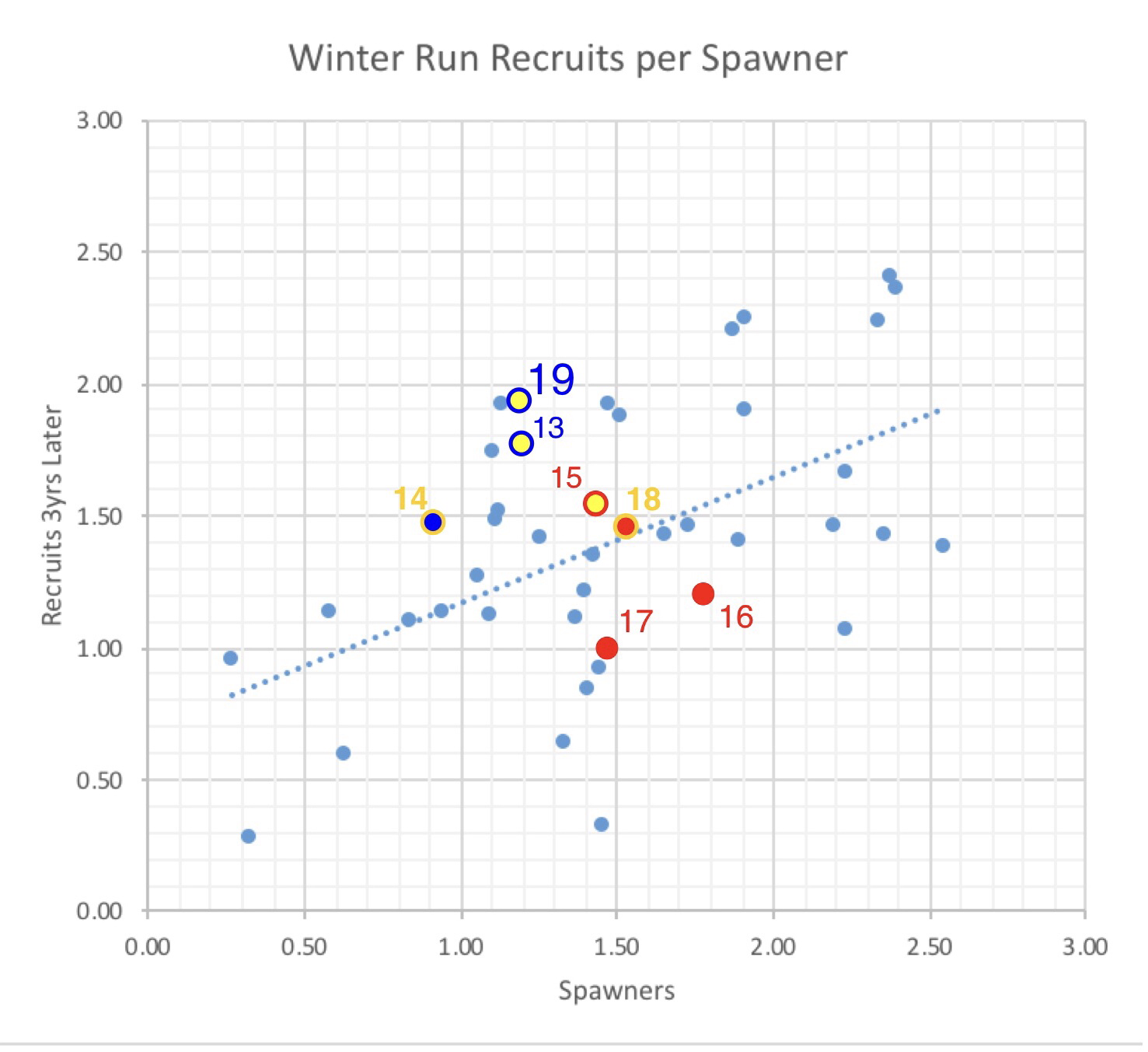

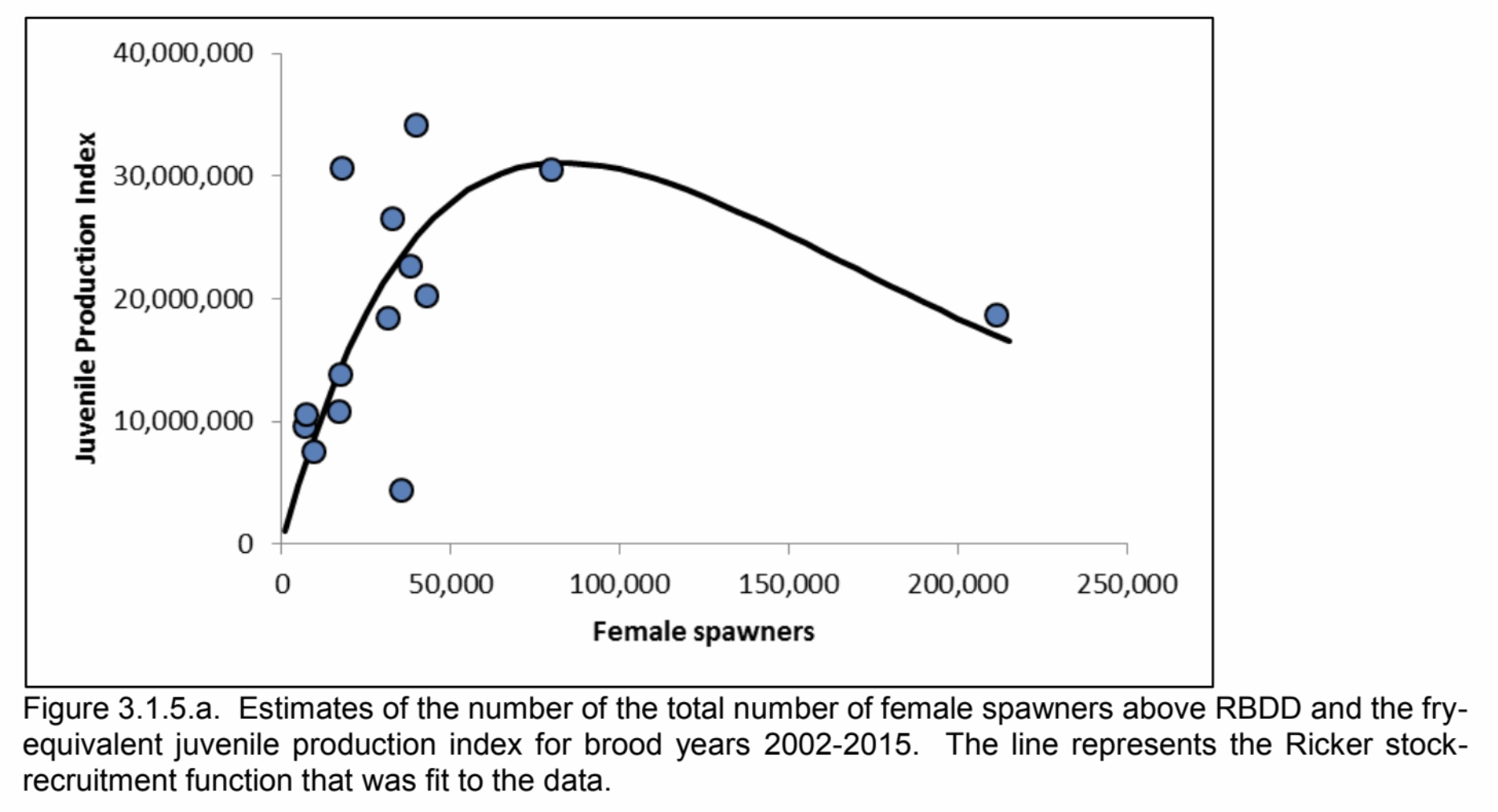

4. Density Dependent Stock Recruitment – “High brood year 2012-2014 spawners from good 2010-2012 conditions led to high density dependent mortality and reduced escapement in 2015-2017” (Figure 2).

This statement appears to imply that excessive redd superimposition by overly abundant spawners in limited spawning habitat led to reduced wild smolt production. It is far more likely that poor returns from brood years 2012-2014 stemmed from other factors.

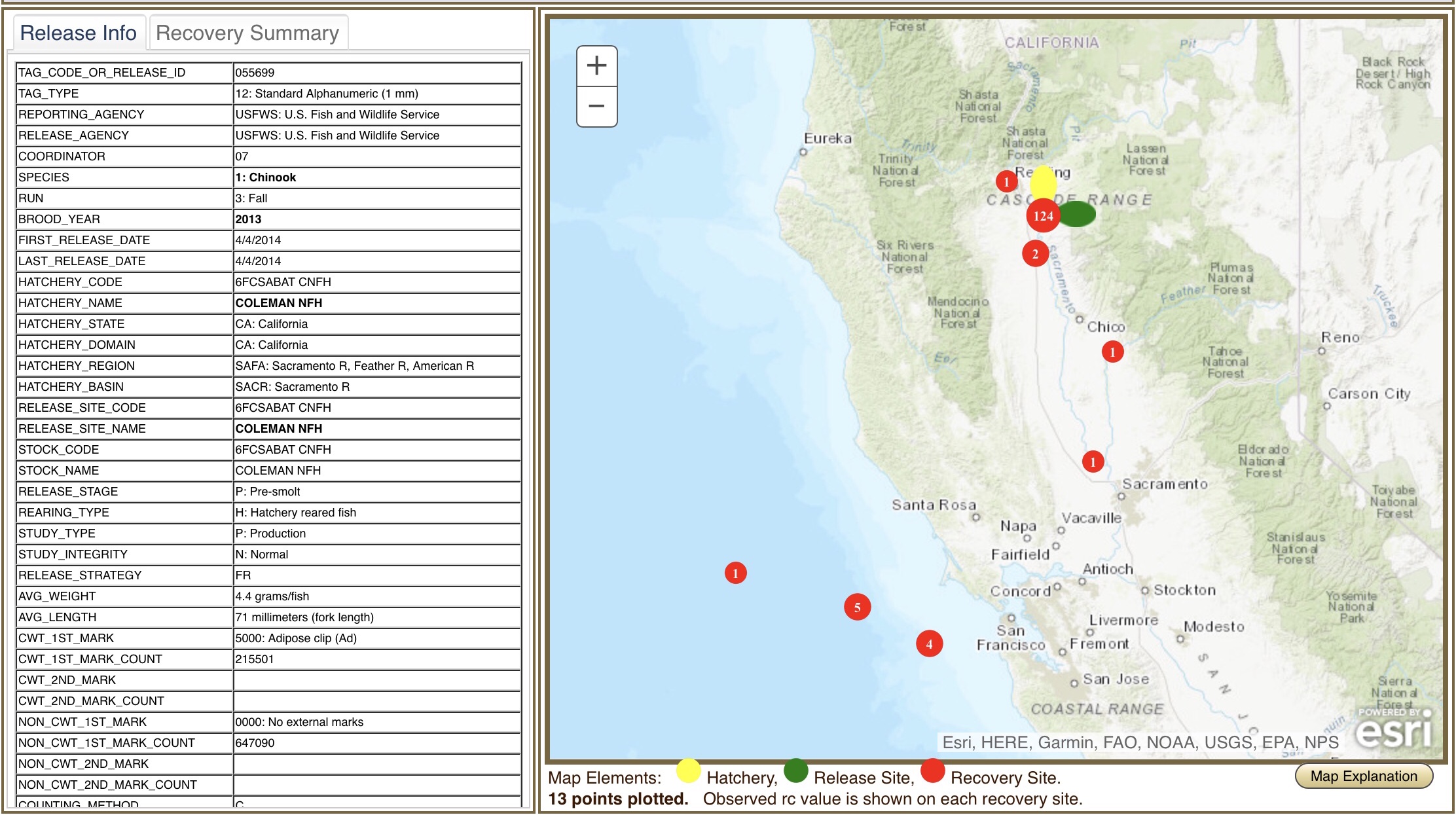

5. Trucking and Straying of Adult Hatchery Fish – “During the three years that contributed to the overfished status, no adults from onsite-releases were estimated to have strayed into the San Joaquin Basin. It was markedly different for offsite releases, however, and adults returning from offsite NFH releases actually strayed into the San Joaquin Basin at higher rates than those returning from offsite CNFH [Coleman National Fish Hatchery] releases. Stray rates generally increased each year during 2015-2017, and they were particularly high in 2017.”

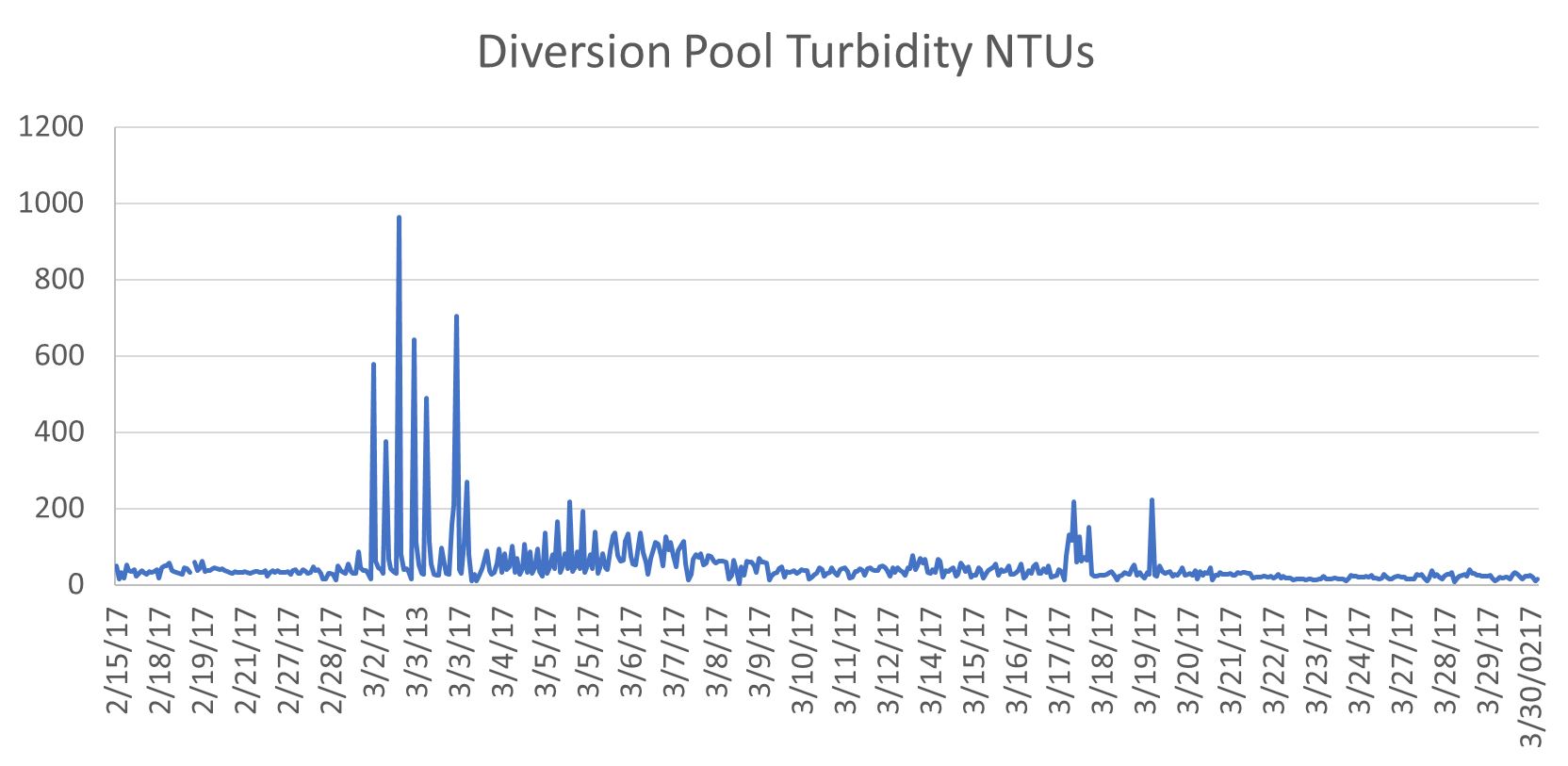

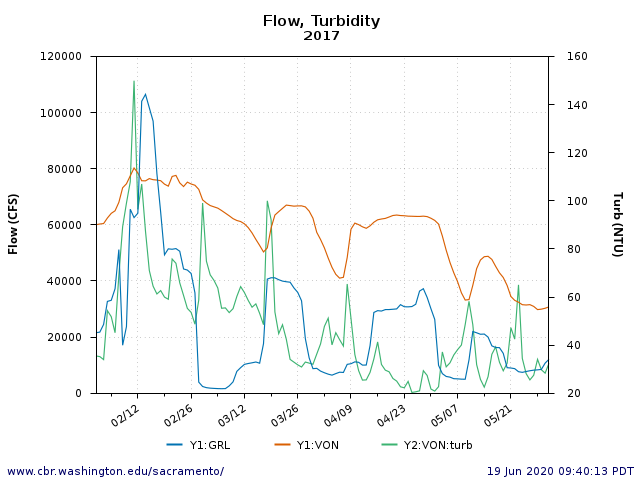

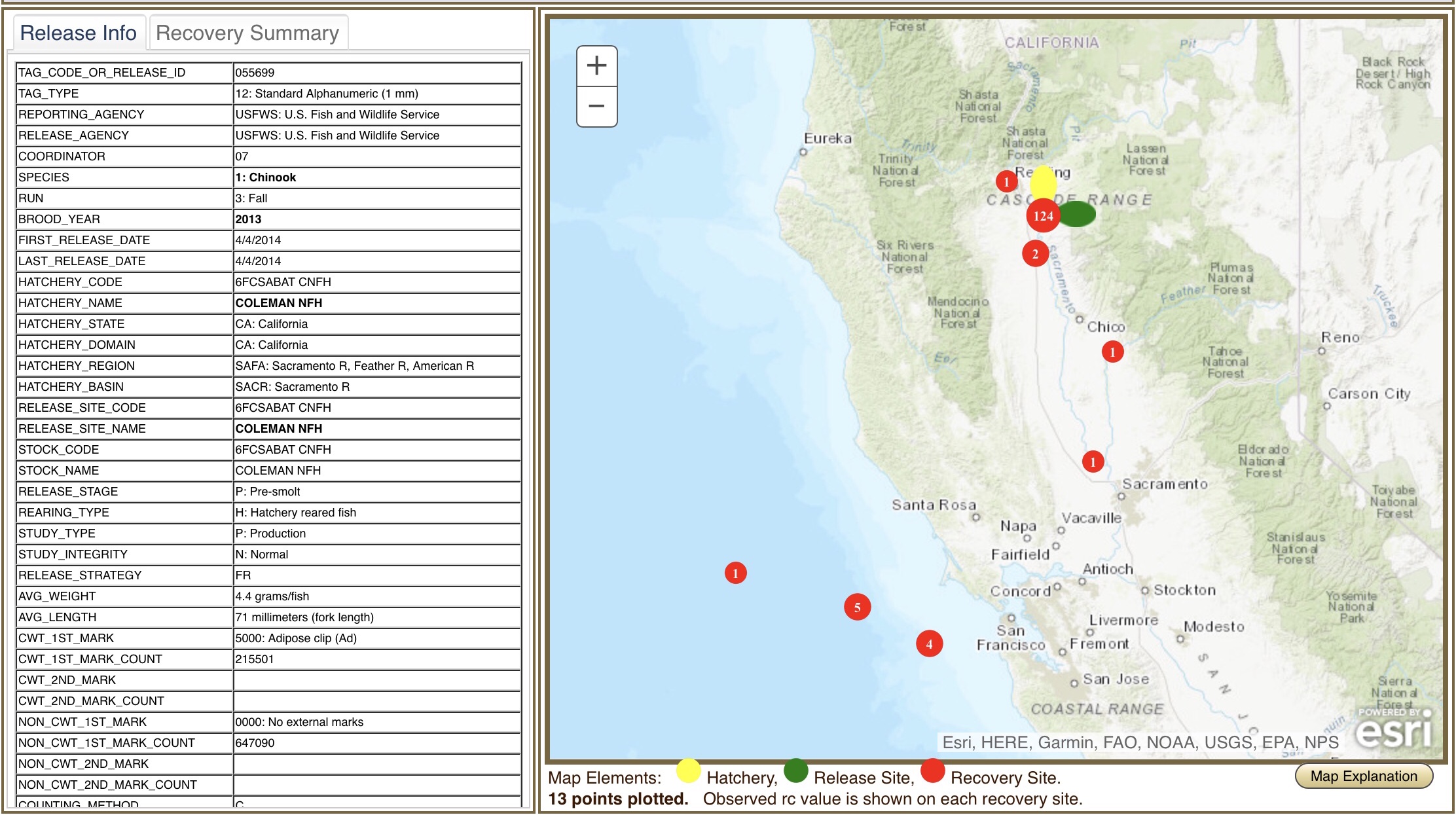

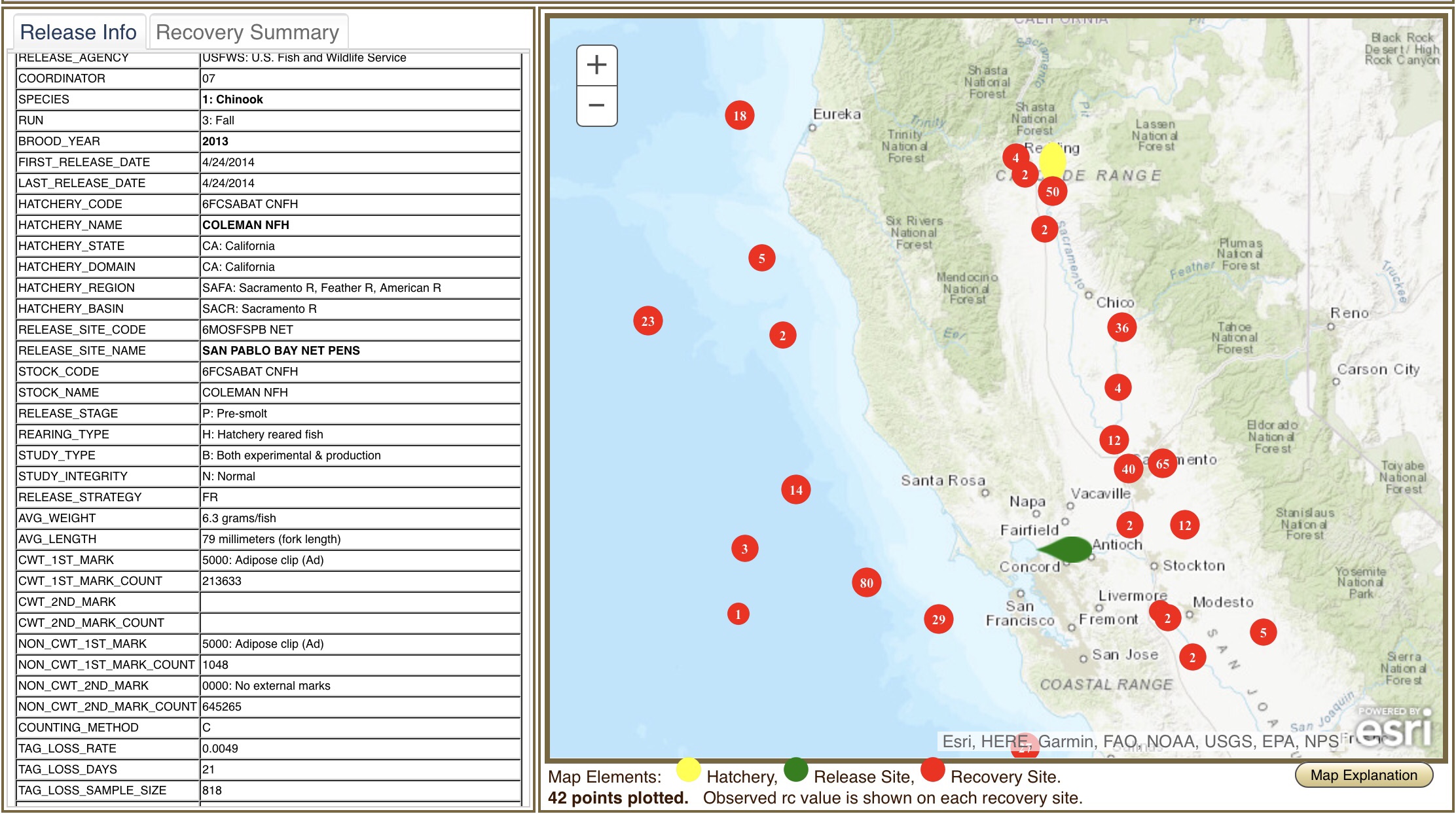

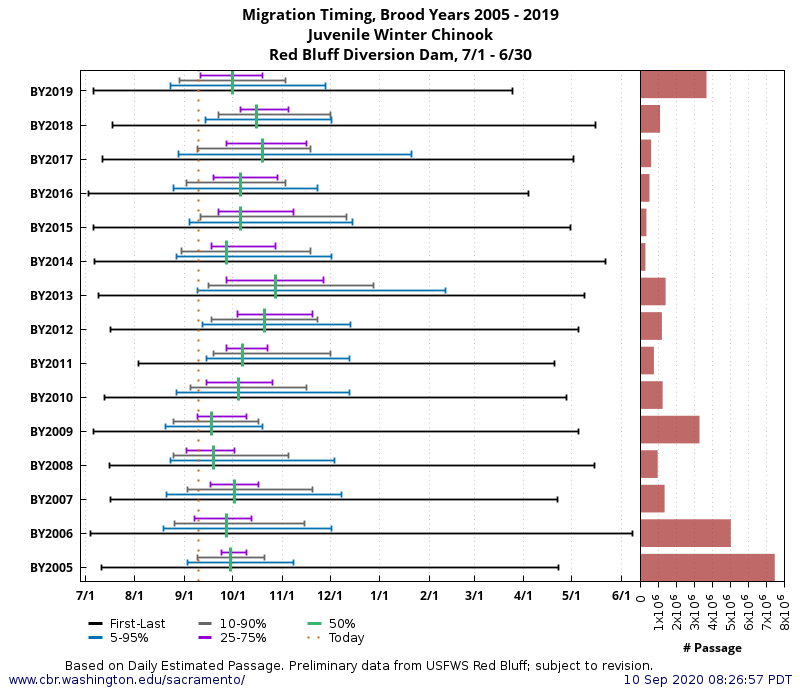

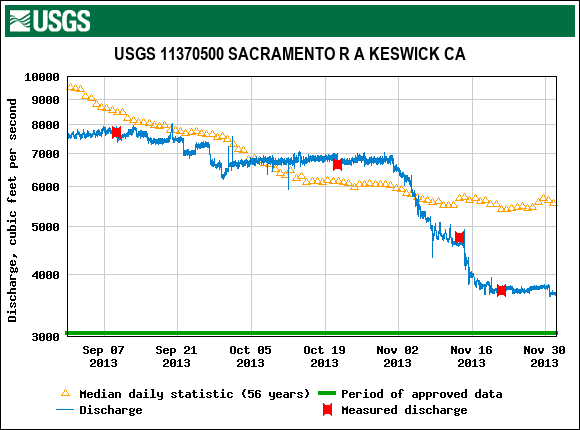

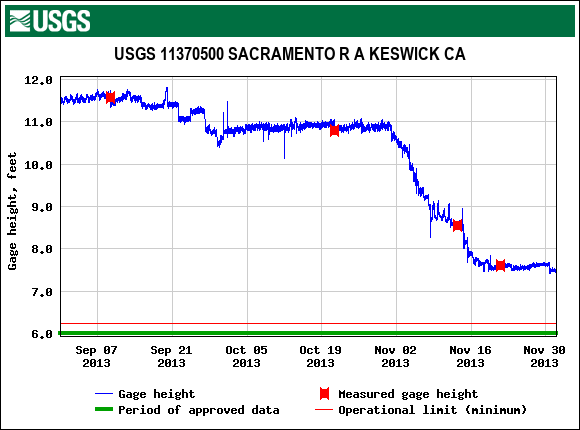

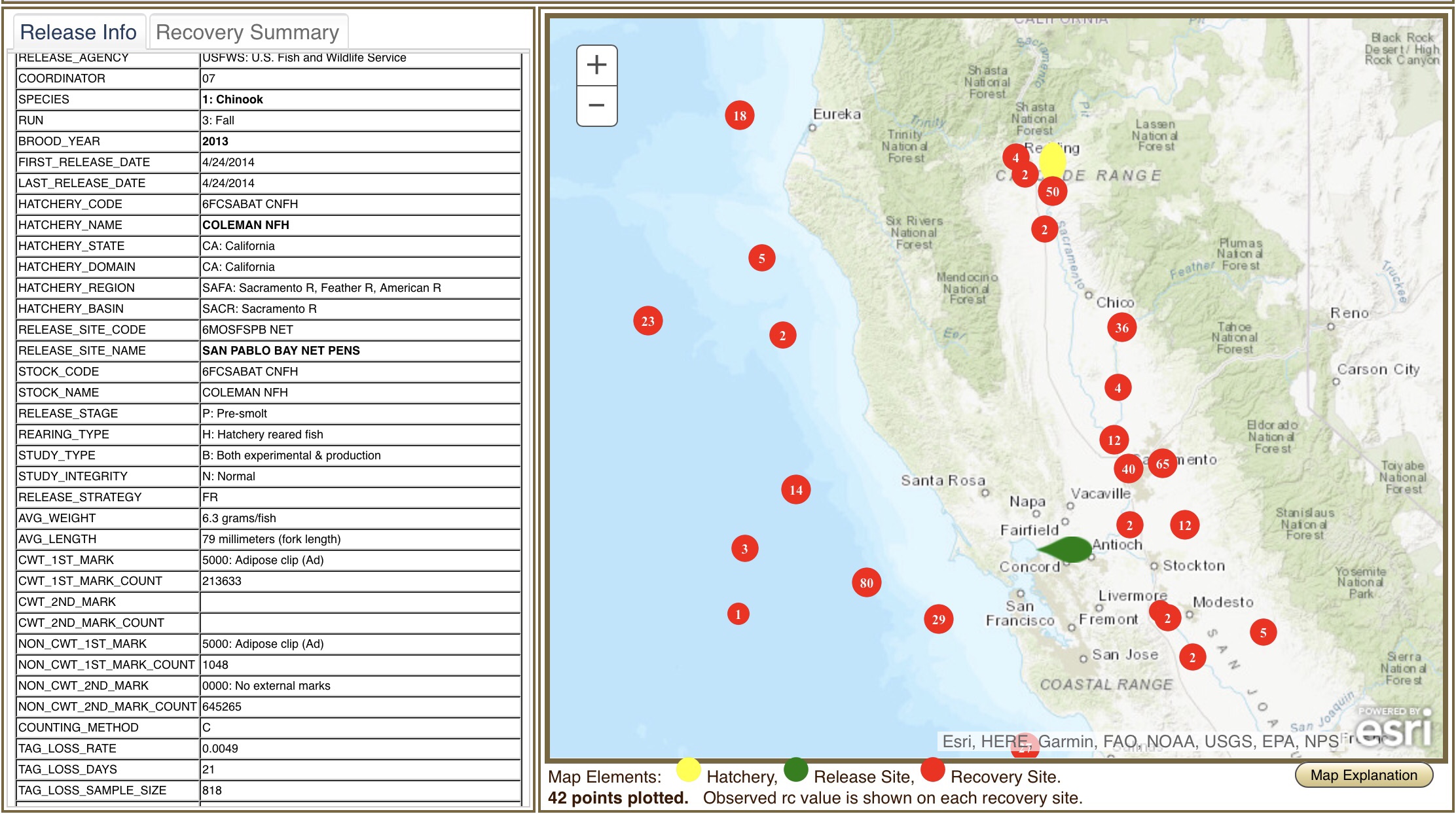

There were many factors affecting hatchery returns from releases in critically dry years. One example is a pair of CNFH releases in April 2014, one at the hatchery in the upper river and one in the Bay (Figures 3 and 4). Although there was more straying from the Bay release group, there was also much greater survival (and fishery contribution). The fish released in the Bay did not have to pass through the lower 100 miles of the river in a drought year.

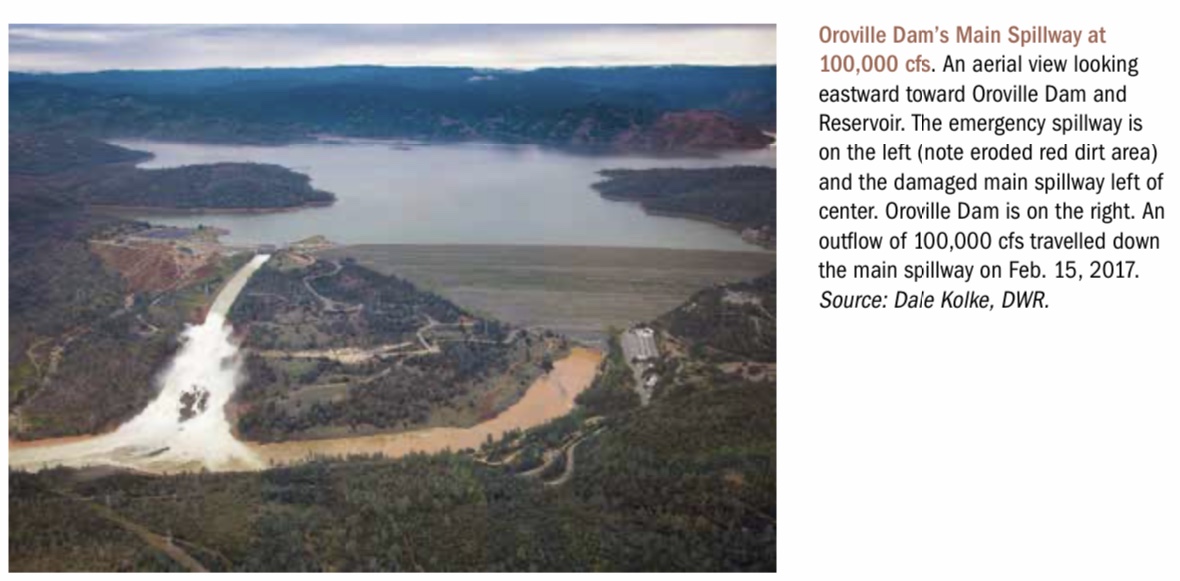

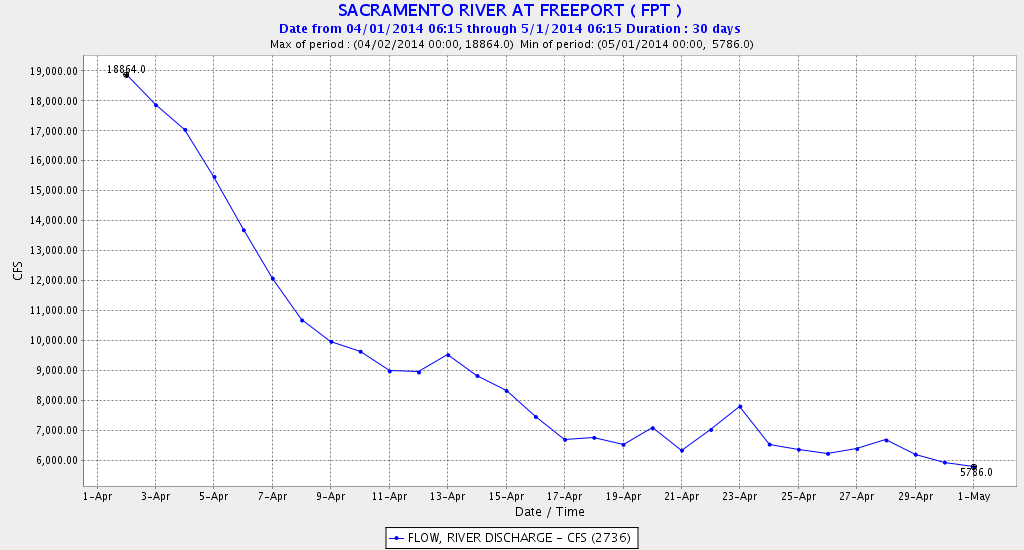

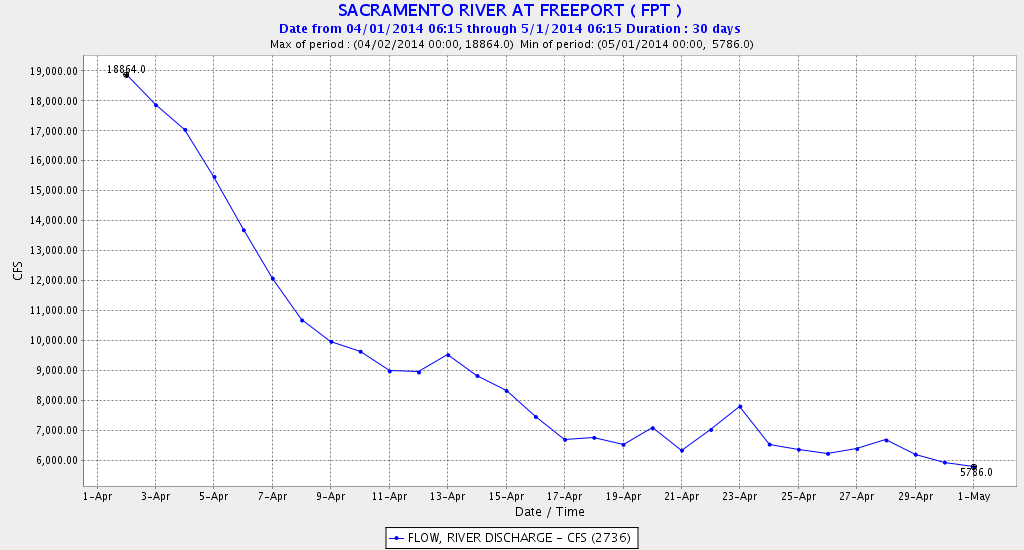

The river group was released under much higher flows (Figure 5) than the Bay group, which likely helped in return homing of the river release group. The Bay group was also larger (by 50% weight), having reared 20 days longer in the hatchery. It was wise to release all the 2015 CNFH smolts in the Bay to ensure survival and contribution to the fisheries, but they imprinted on a wide combination of Central Valley tributary flows leading to straying.

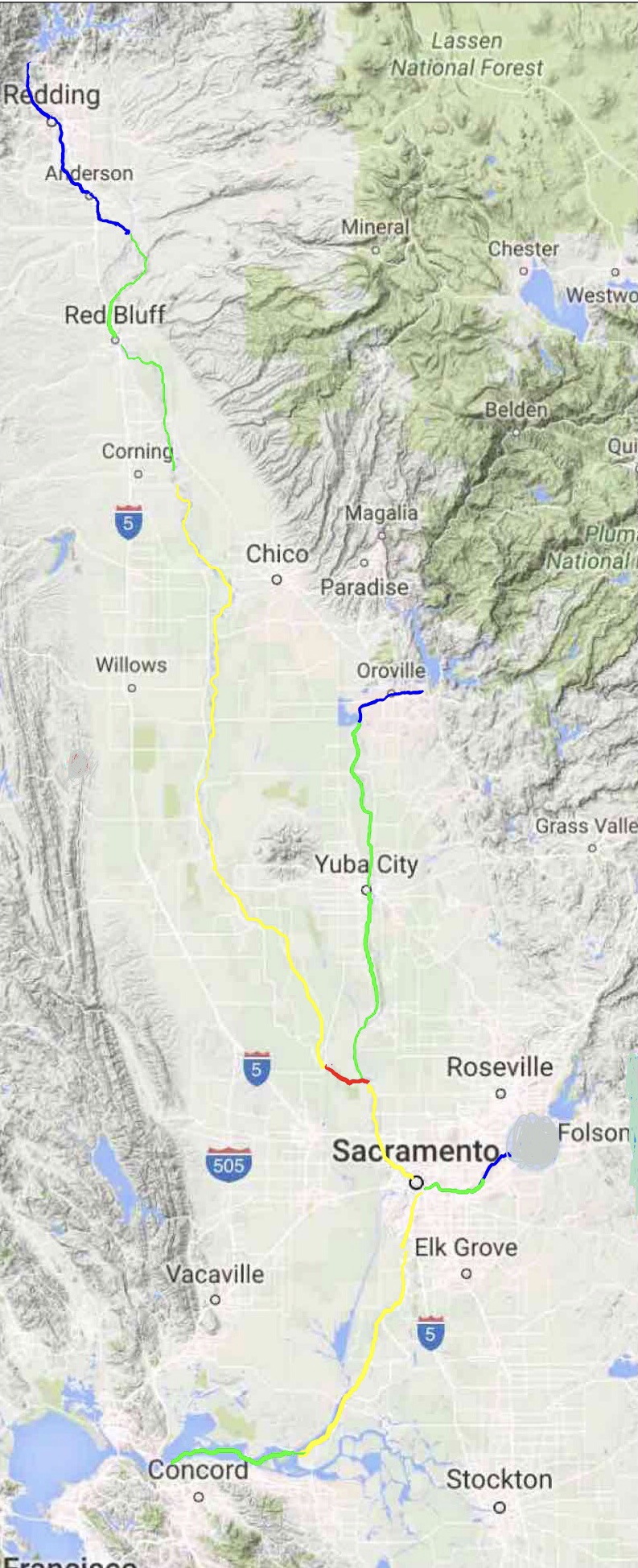

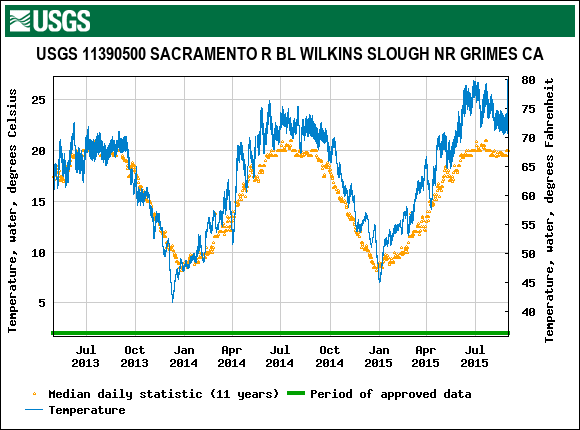

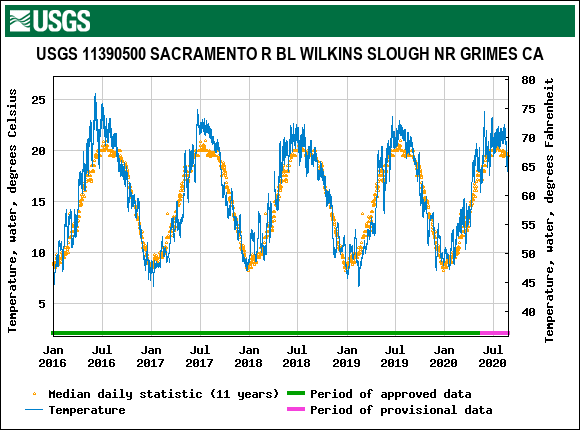

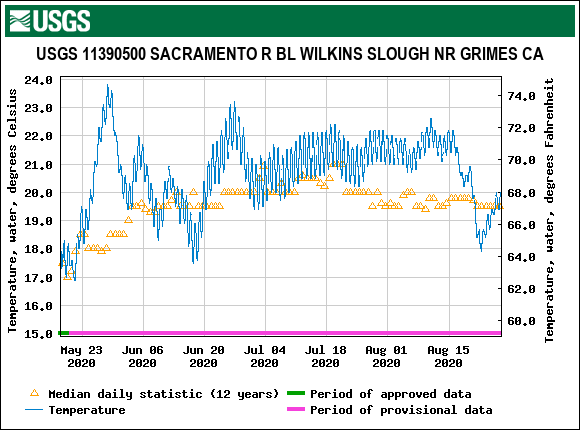

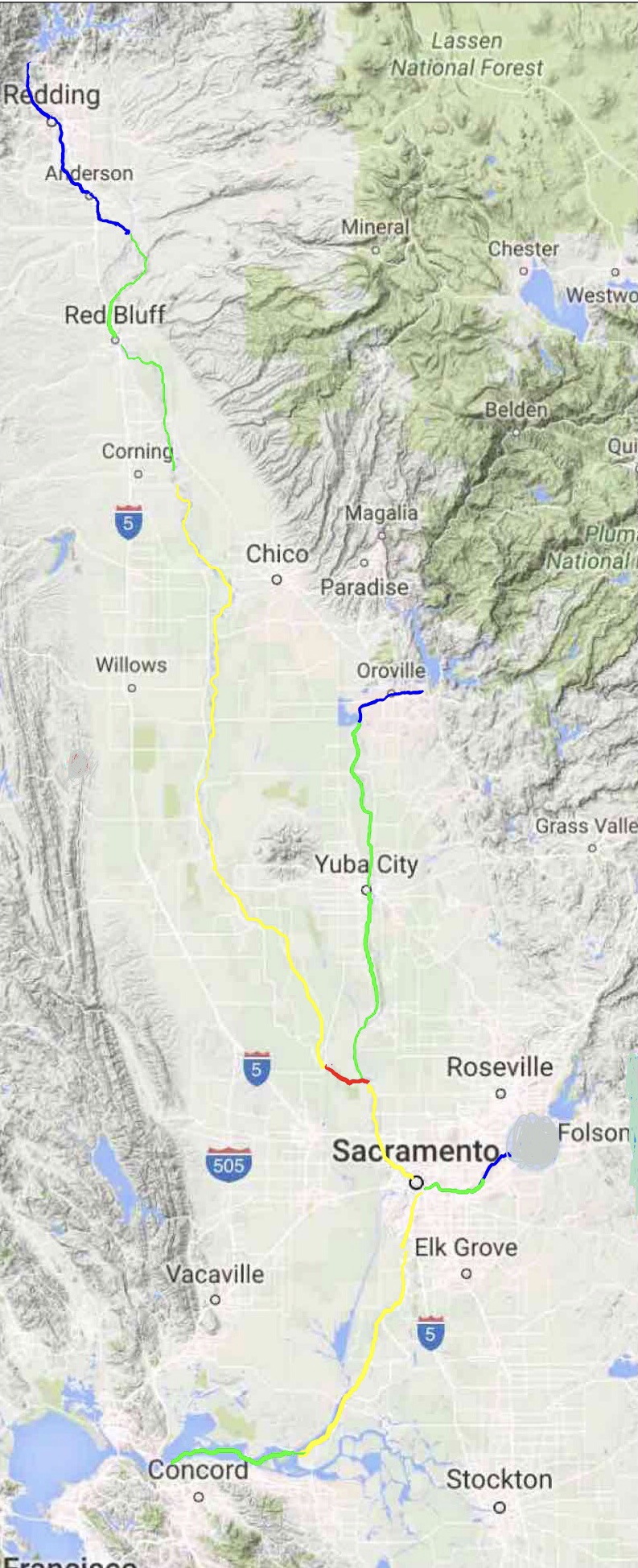

Another factor that likely increased CNFH returning adults straying was poor summer migrating conditions in the lower Sacramento River above the mouth of the Feather River (Figure 6). These conditions cause many returning adults to choose the American, Feather/Yuba, and Mokelumne Rivers.

6. Increased Harvest of Adult Stock – “Offsite-released fish were noticeably more prone to harvest once inside the Sacramento Basin. The entire SRFC stock experienced elevated in-river harvest rates during 2016 and 2017, largely due to the migratory behavior of spawners returning from offsite hatchery releases.”

Note higher harvest was also attributed to much better returns of Bay releases, as well as release timing and homing imprinting problems with Bay releases.

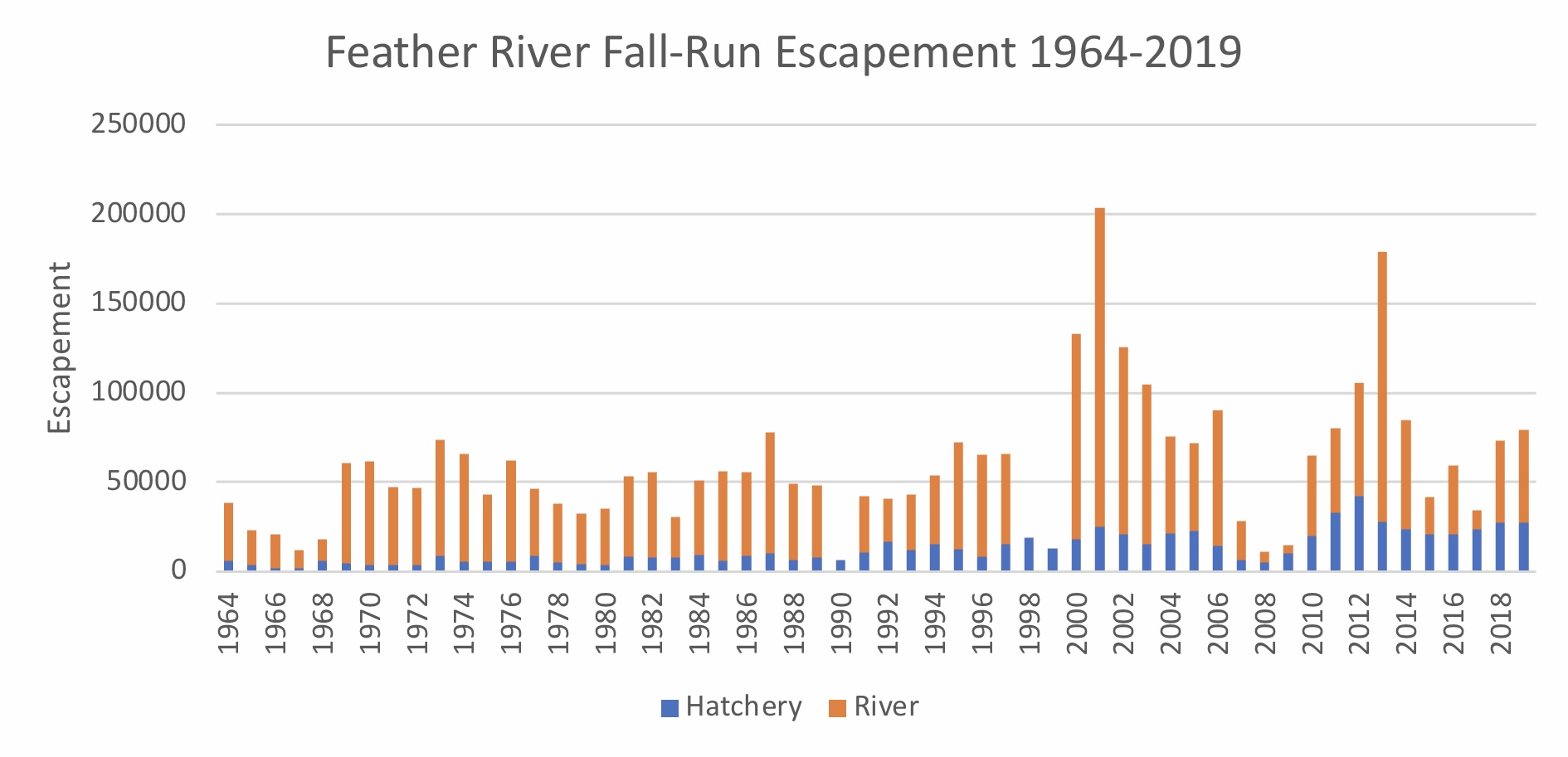

7. Hatcheries – “A common result across the CDFW reports is that hatchery-origin fish routinely make up the majority of natural area escapement and harvest, and at various levels of escapement.”

While hatcheries have these inherent problems, there would be few salmon and minimal salmon fisheries in California without hatcheries. However, the plan promotes the building of natural/wild components of SRFC populations. The problem is that adjusting and managing runs through fishery harvest management is not going to help make that happen.

The report recommends the following actions to rebuild the stock (fishable population) to allow Maximum Sustainable Yield (122,000 returning wild adults).

Recommendation 1 – rebuild in 3 years. Note the stock has met its goal since 2017 because brood-years’ 2015-2018 were reared in normal or wet years.

Recommendation 2 – adopt one of the alternative strategies:

- Alternative 1 – status quo (rebuilds in three years

- Alternative 2 – reduce harvest by 30 %

- Alternative 3 – reduce harvest by closing southern-range ocean and all in-river fisheries (rebuilds in two years)

Recommendation 3 – eliminate or limit fall ocean fisheries

Recommendation 4 – limit harvest quota fisheries

Recommendation 5 – provide recommendations to the Council for restoration and enhancement measures within a suitable time frame. “It is recommended that the Council direct the Habitat Committee to work with tribal, federal, state, and local habitat experts to review the status of the essential fish habitat affecting SRFC and, as appropriate, provide recommendations to the Council for restoration and enhancement measures within a suitable time frame, as described in the FMP.”

Note that such processes have occurred on multiple occasions over the past several decades. Multi-stakeholder efforts abound, including the comprehensive the Central Valley Salmon and Steelhead Recovery Plan and various federal biological opinions and state take permits, as well as associated environmental reviews.

Further Recommendations

- Consideration should be given to estimating productivity of natural-area spawners and

development of management objectives for this component of the SRFC stock, as has

previously been recommended by CA HSRG (2012) and Lindley et al. (2009).

- How far did water quality deviate from optimal conditions.

- Evaluate the effects of redd dewatering

- Determine factors relating to straying of trucked hatchery smolts

- Evaluate water temperature conditions in spawning reaches.

- Evaluate why recovery has favored hatchery components

The plan also offers a summary:

Limitations on our ability to accurately explain and forecast annual variations in Pacific salmon production remain, in part because of uncertainty in the factors responsible for salmon mortality and from the effects of climate warming on the marine distribution and abundance of salmon. It is more important than ever to promote cooperative and innovative international research to identify and better understand the ecological mechanisms regulating the distribution and abundance of salmon populations for sustainable salmon and steelhead management. North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission Bulletin No. 6: 501–534, 2016 .

Conclusion

Most of these recommendations miss the mark. The claim that there is too little understanding also misses the mark.

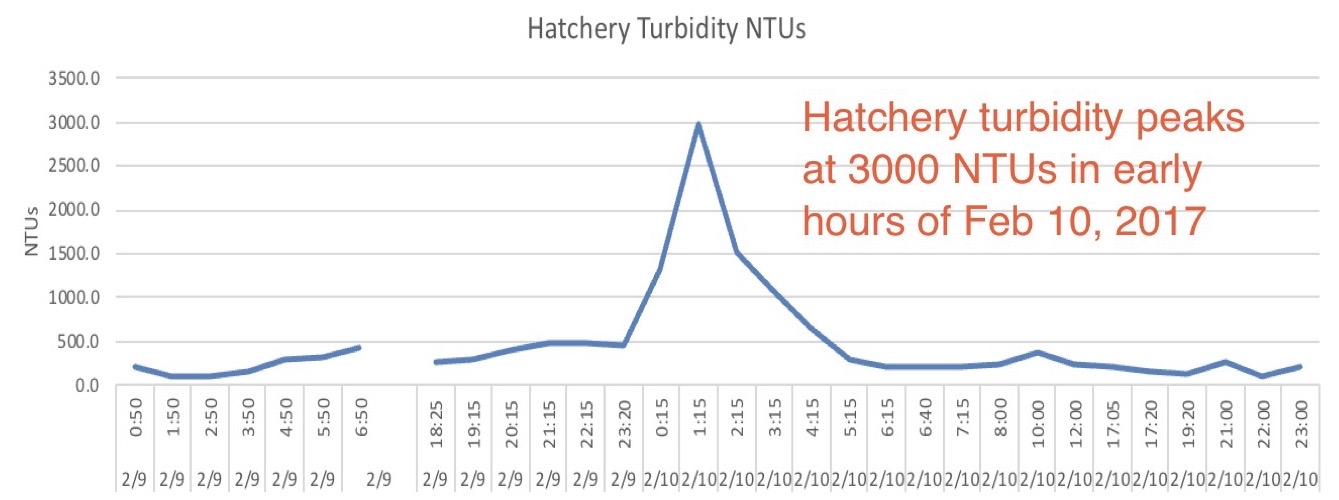

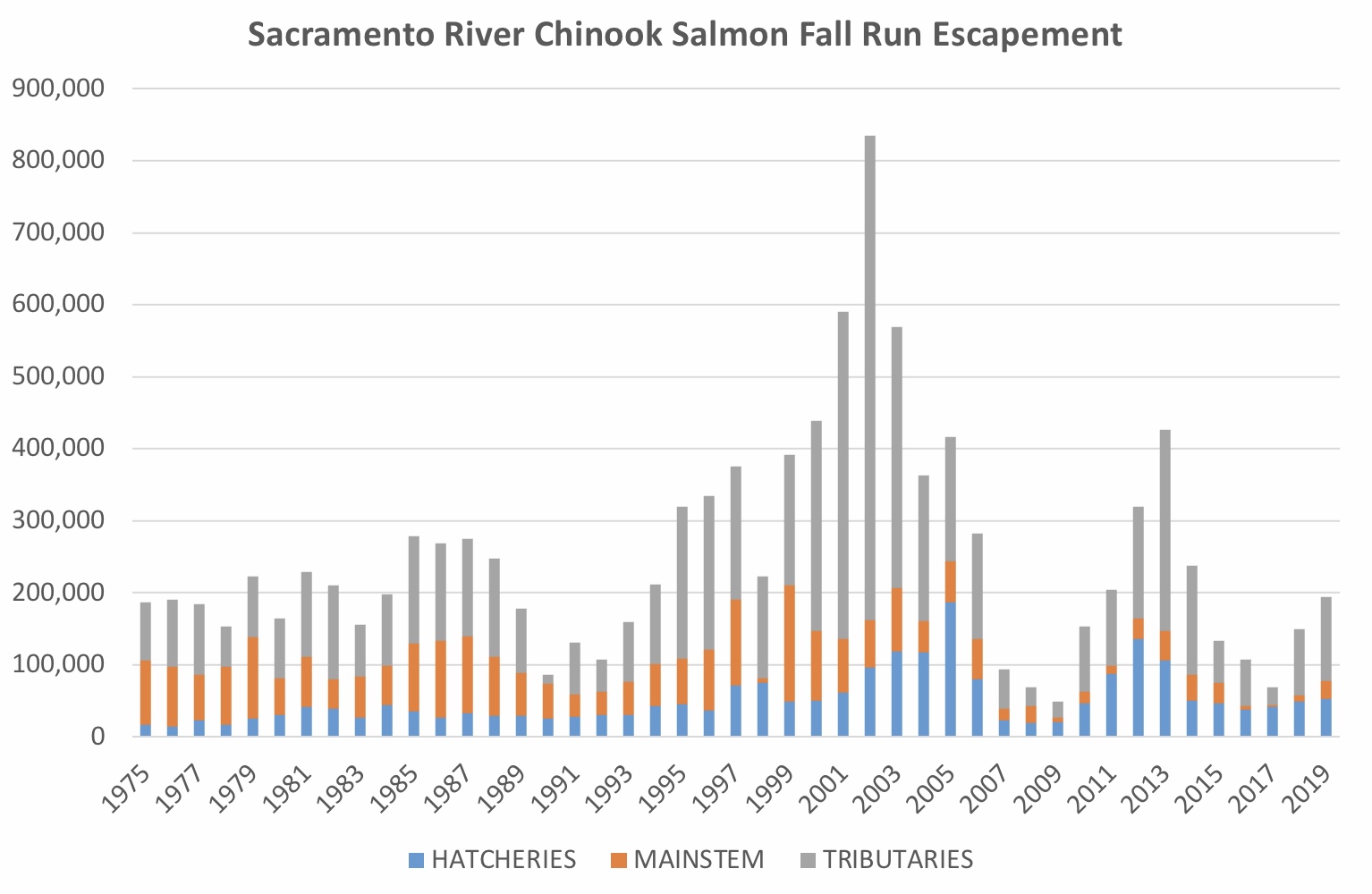

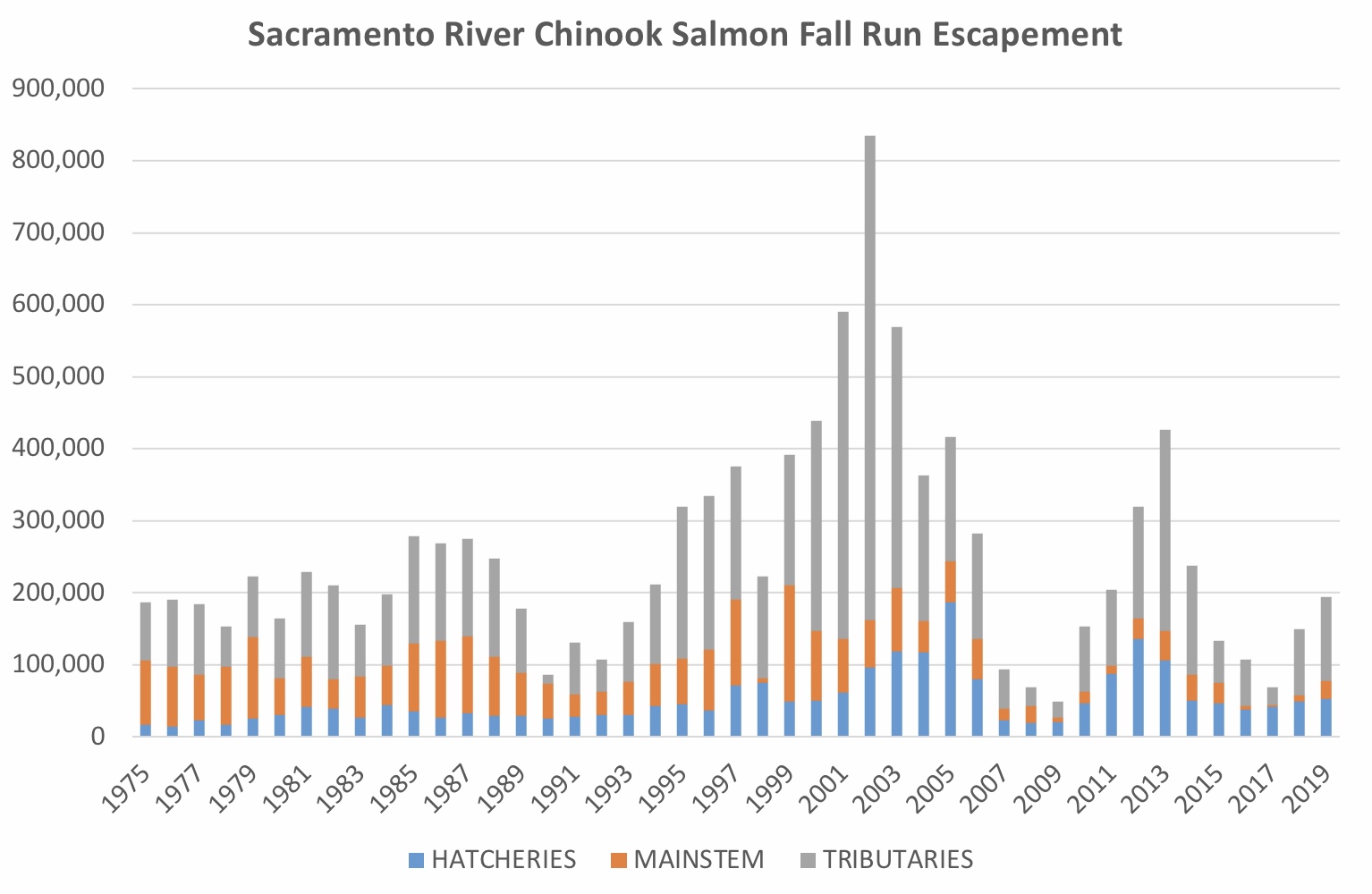

Sacramento River fall-run Chinook salmon escapement has benefitted from wet year periods (1995-2006 and 2010-2012; Figure 7) and off-site hatchery smolt releases to the Bay and ocean coast sites. Escapement has suffered immensely from drought conditions, which dramatically limited wild and hatchery juvenile survival (1987-1992, 2007-2009, and 2013-2015).

The plan should have focused more on the management of wild and hatchery smolt survival factors in drought years rather than adjustments to fishery harvest and hatchery production. As written, the plan will not improve the ability of the stock (population) to sustain harvest in the future, especially since the underlying problems are getting worse.

Figure 1. Sacramento River Fall Run Chinook total hatchery and in-river spawning escapement 1970-2017. SMSY = Maximum Sustained Yield target. MSST = Minimum Stock Size Threshold (minimum acceptable target). Note MSY target was not met in 2007-2009 and 2015-2017. Source of Figure: Salmon Rebuilding Plan.

Figure 2. Spawner numbers versus juvenile production index. Source of Figure: Salmon Rebuilding Plan.

Figure 3. Returns from April 4, 2014 SRFC smolts released at Coleman hatchery. Source: https://www.rmpc.org

Figure 4. Returns from April 24, 2014 SRFC smolts released in Bay. Source: https://www.rmpc.org

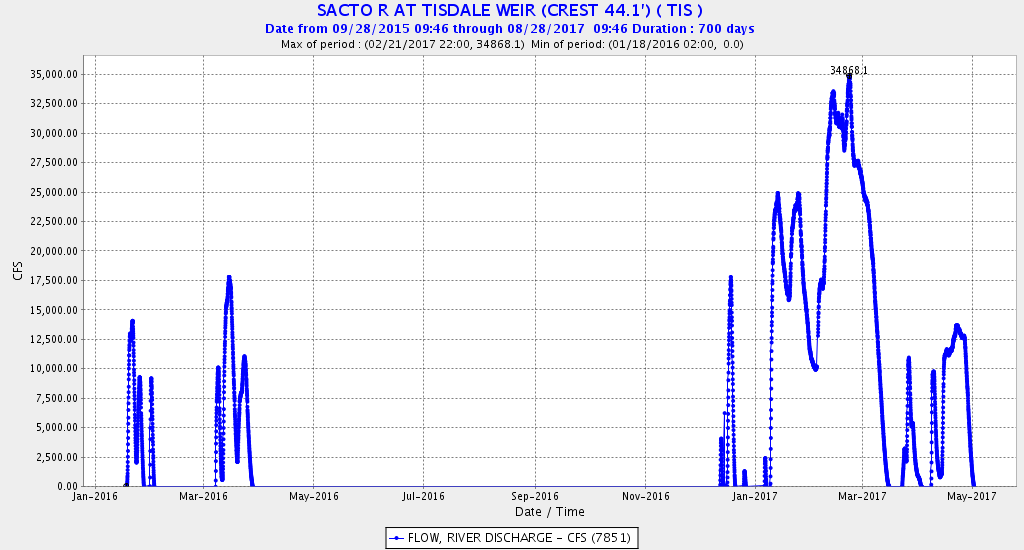

Figure 5. Daily Sacramento River flow at Freeport in April, 2014.

Figure 6. Migratory conditions for returning CNFH salmon in late summer. Blue regions are primary spawning areas. Green are migration and holding areas with adequate late summer water temperatures. Yellow areas are migration routes with excessive stressful water temperatures. Red area has blocking/lethal water temperatures. Note that conditions would encourage straying of upper Sacramento-bound salmon into cooler tributaries.

Figure 7. SRFC escapement 1975-2019.