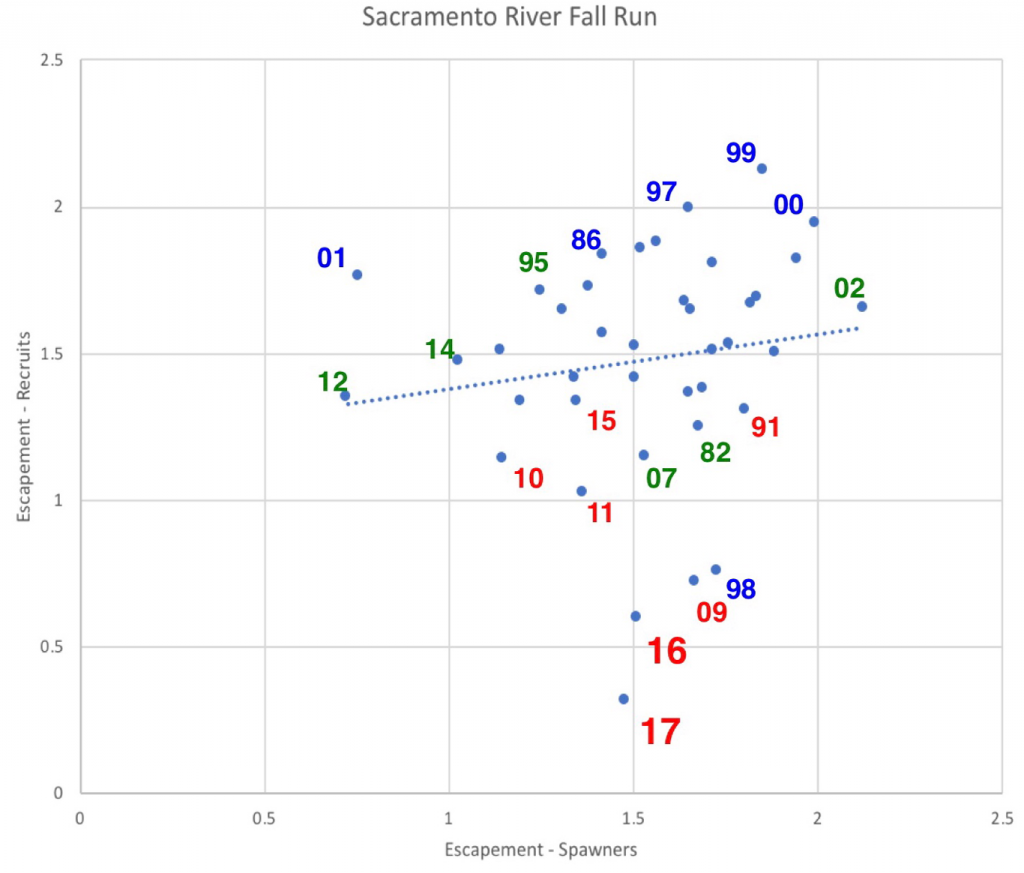

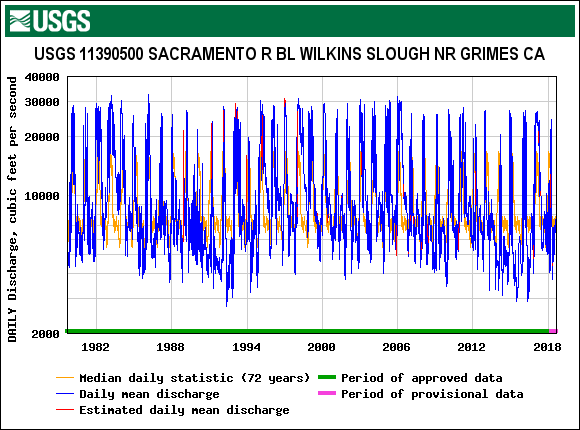

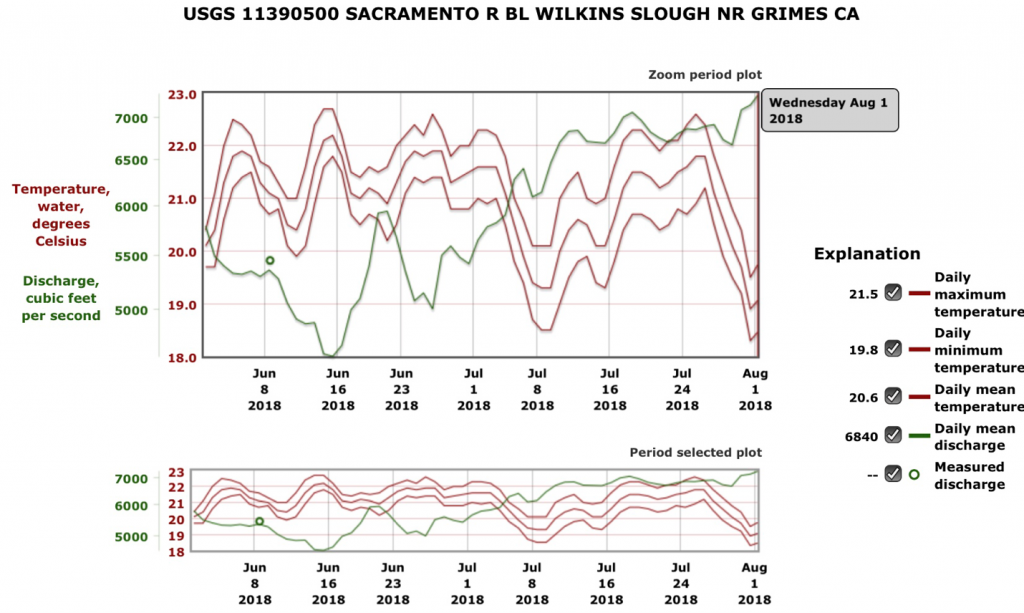

The Yuba River had a record low fall Chinook salmon run in 2017 (Figure 1). Why are our salmon populations plummeting in the Yuba River and many other rivers in the Central Valley watershed? It is because hatchery and wild salmon survival was poor in rivers, the Bay-Delta, and ocean during the historic 2013-2015 drought.

What is it about the Yuba salmon run that can tell us something about the overall salmon decline in the Central Valley?

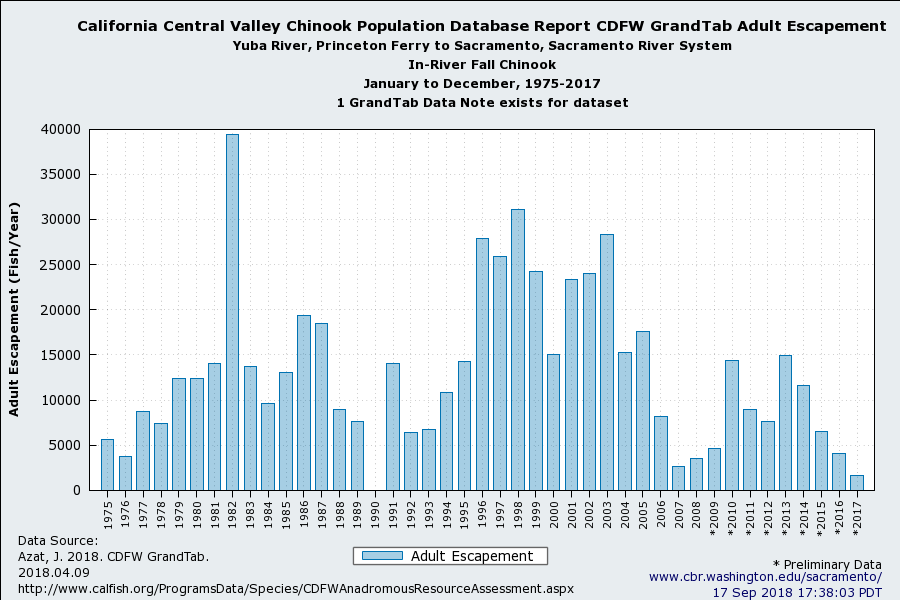

- First and foremost, the Yuba run consists predominantly of strays from many of the Central Valley salmon hatcheries. The Yuba has no hatchery. Many of the adult salmon in the Yuba have their origin from smolts produced at Battle Creek, Feather River, American River, Mokelumne River, and Merced River hatcheries. Hatchery salmon survival and production was generally lower in the drought, thus contributing fewer strays to the Yuba. Feather River Hatchery production was an exception (Figure 2) because its managers trucked and barged many of its smolts to the Bay.

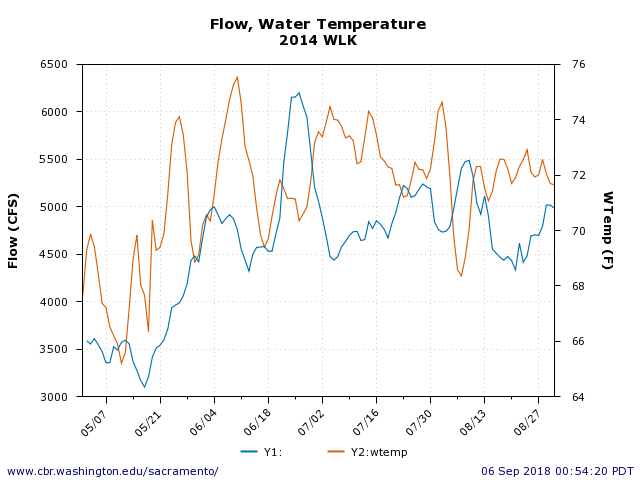

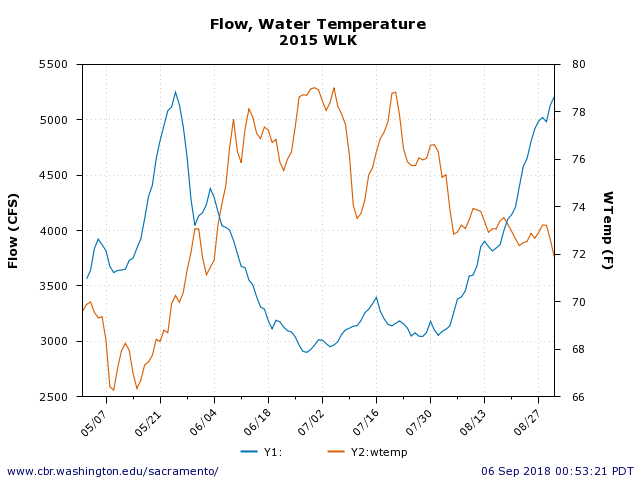

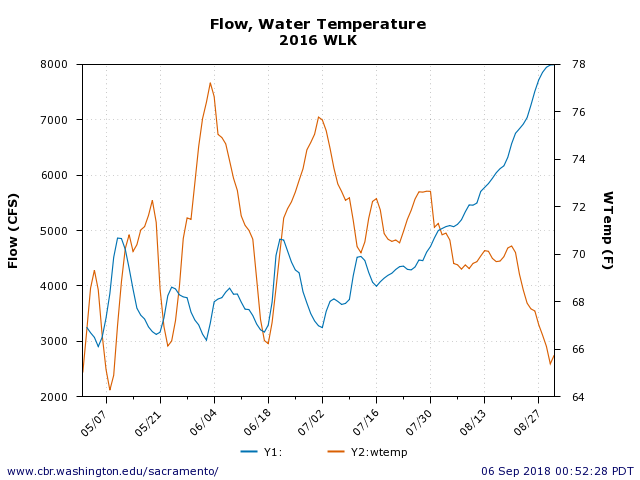

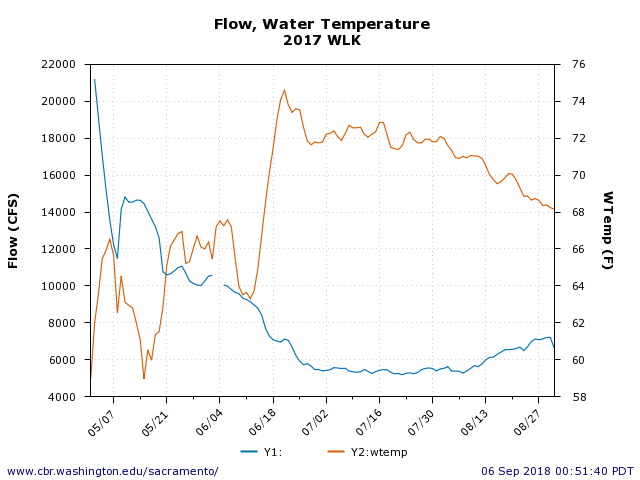

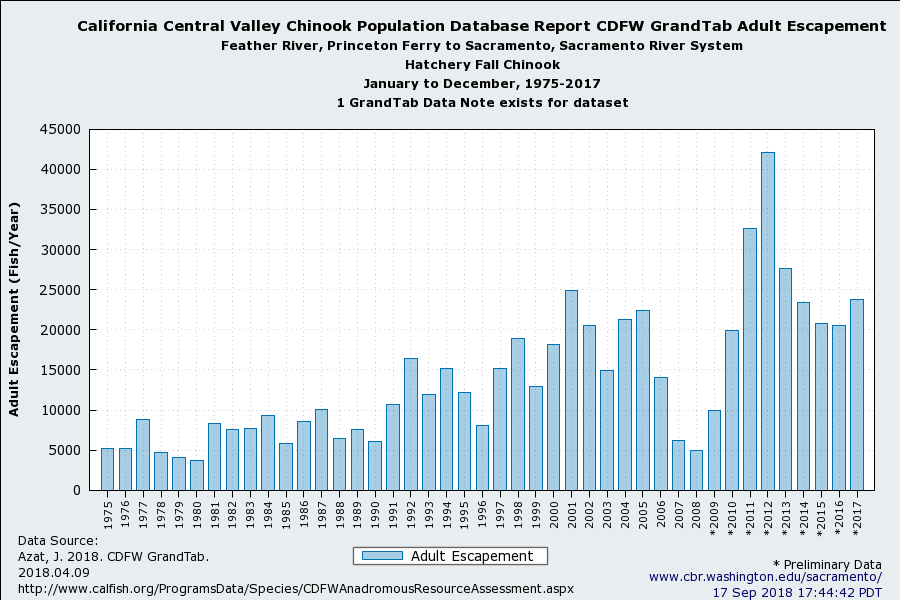

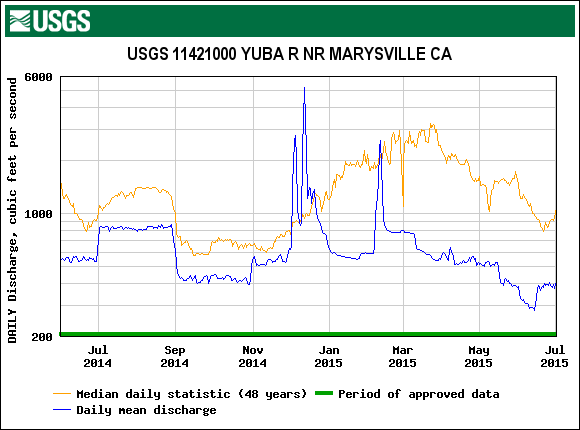

- Second, production of wild salmon was lower during the drought on the Yuba and other Valley rivers. During the spawning runs in late summer and fall 2014, flows were low (Figure 3) and water temperatures were high, leading to high pre-spawn mortality and poor egg viability. Low flows led to less available and lower quality spawning habitat. Spawning in low-flow gravel beds led to redd scouring in late fall and early winter storm flow events. Low winter and early spring flows led to poor rearing and emigration survival.

- Third, salmon spawning and rearing habitats (gravel beds, riparian vegetation, channel morphology, large woody materials, etc) are lacking or declining in quantity, quality, and availability. The Yuba’s prime spawning and rearing habitats above Daguerre Point Dam suffer from lack of gravel replacement supply below Englebright Dam in the upper reach and confinement of the river channel and floodplain in the lower reach within the historic dredge-pile levees of the Goldfields. Likewise, habitats in the lower river below Daguerre also suffer, while favoring native and non-native predatory fishes that further limit survival of young salmon.

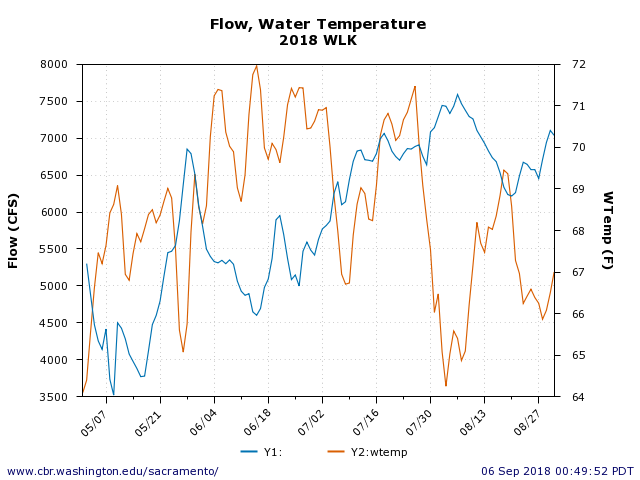

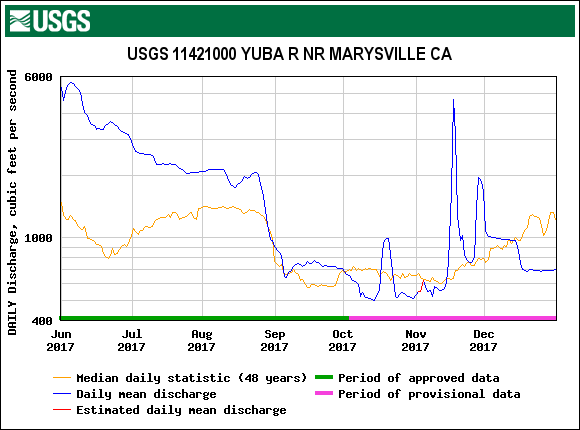

- Fourth, low fall flows in 2017 (Figure 4) also likely reduced attraction of adult spawners, and possibly caused redd dewatering and subsequent redd scouring.

So what needs to be done to increase the Yuba (and other Valley rivers) salmon runs?

- Increase survival of all Valley hatchery smolts by trucking and barging. Battle Creek Hatchery strays are regularly the greatest component of the Yuba run.

- Increase fall base flows into the upper portion of their optimal spawning flow range (from 500 cfs to 700 cfs) to attract spawners, lower water temperatures, maximize spawning habitat, and reduce potential redd dewatering and scour after spawning. Lower summer-fall base flows also contribute to exaggerated thalweg channel scour and downcutting, and loss of side channels because of the confined channel.

- Increase winter-spring flows to improve fry/fingerling/smolt survival during rearing and transport to Bay-Delta and to reduce predation by pikeminnow, striped bass, trout, and shad in the lower Yuba River below Daguerre Point Dam.

- Improve winter fry rearing habitat available at low winter flows by improving riparian vegetation, adding large woody materials to the low flow channel, and opening the channel and floodplain to increase surface area, increasing distributary channel networks, and lowering channel velocities.

- Add gravel to the upper spawning reach downstream of Englebright Dam.

- Capture some of the natural juvenile salmon production at Daguerre Point Dam and transport to Verona for barge or truck transport to the Bay.

- Stock Feather River Hatchery smolts into the lower Yuba River.

- Rear Feather River Hatchery fry in lower Yuba River floodplain habitats including managed rice fields.

- Recover naturally produced juvenile salmon trapped in floodplain habitats after high flow events.

For more on Yuba River salmon and their habitat see:

http://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/?p=1559

https://www.fws.gov/Lodi/instream-flow/Documents/Yuba%20River%20Spawning%20Final%20Report.pdf

Figure 1. Chinook salmon fall run Chinook salmon population estimates from 1975 to 2017 for the Yuba River.

Figure 2. Hatchery returns to Feather River 1975 to 2017.

Figure 3. Yuba River flow at Marysville June 2014 through June 2015 with 48-year average flow. Note low summer-fall flows and high December flows in 2014, and low spring flows in 2015; these stresses likely contributed to record low 2017 salmon run.

Figure 4. Yuba River flow at Marysville June 2017 through December 2017 with 48-year average flow. Note low October to mid-November flows followed by high flows in late November.