Large amounts of rearing habitats for young salmon were lost in the upper Sacramento Valley Basin when Shasta and Keswick Dams were built. Loss of this rearing habitat (located in smaller, shallower river channels upstream of the dams – like the McCloud River) was considered one of the numerous reasons for the listing of the winter-run Chinook as endangered. Since dam construction, young salmon emerging from main-stem spawning areas downstream of the dams must now contend with the severe rigors of a large, deep river channel. It is generally acknowledged that the quality of rearing habitats in those upstream areas was superior to habitats below the dams (Vogel 2011).

Although significant efforts have been made to increase the quantity and quality of spawning habitats below the dams, minimal progress has occurred on rearing habitats. Massive amounts of spawning gravels have been added to the upper Sacramento River downstream of Keswick Dam, but there are indications that rearing habitats may be an equally important, if not more-important, factor limiting the fish populations. As pointed out by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS),“ … there would be little value in increasing the quantity of available spawning gravel if the problem that actually limits juvenile production is lack of adequate rearing habitat” (USFWS 1995). Astonishingly, more than two decades later and despite over 1 billion dollars spent on salmon restoration, that potential dilemma remains unresolved.

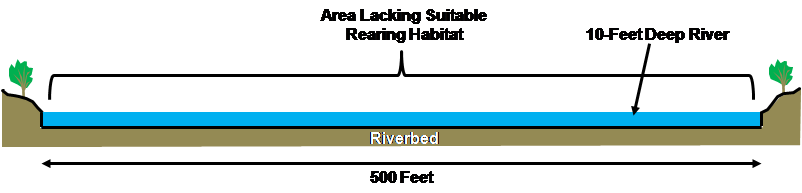

Present-day rearing habitats are considered very limited and predation during juvenile rearing is believed to be a stressor of very high importance (NMFS 2014). The best habitats, in conventional theory, would be on the channel fringes. Indeed, some such areas with desirable attributes do exist, but are sparse. However, due to the nature of the river reach where most winter-run salmon spawn in deep water, many of the ideal habitat characteristics for rearing are lacking (e.g., appropriate velocities and cover). Subsurface structures like woody debris are severely deficient and would be challenging to restore due to lack of significant recruitment and periodic extremely high-flow events (Shasta Reservoir flood-control releases) that would dislodge this essential feature. In many areas where salmon spawn, the river is wide (e.g., 500 feet) and channel edges are deep (Figure 1). Fry emerging from redds in the main-stem riverbed encounter a paucity of velocity and predator refugia. Underwater observations and sonar camera footage near artificial structures in deep water (e.g., bridge piers) have frequently shown extensive salmon rearing activity, but may suggest the fish are utilizing those areas because insufficient other natural structures on the riverbed are limited or absent (Vogel 2011).

Figure 1. Cross-sectional profile of the upper Sacramento River in an area 500 feet wide and 10 feet deep (scale is approximate).

Based on many years of observations in the main-stem Sacramento River, large schools of young salmon exhibit a very strong affinity for specific habitats unique in a large, deep river channel. This circumstance is a quandary for salmon fry upon emergence from redds positioned in deep water and long distances from channel edges. The weak-swimming fry are immediately exposed to high near-bed water velocities and minimal refugia to escape from predatory fish such as rainbow trout that are very abundant in areas where winter-run Chinook spawn. The region where young salmon have been observed in deep channel areas include behind tail spills of redds and bridge piers, and in eddies adjacent to vertical bedrock walls. It is particularly evident that large schools of salmon choose areas where eddies exist adjacent to high water velocity shear zones. This provides the fish necessary velocity refugia while simultaneously gaining ready access to drift food organisms, thereby minimizing energy expenditure. Unfortunately, those same areas do not provide refuge from predatory fish.

The following are examples of salmon rearing in the deeper waters of the upper Sacramento River. [It must be noted that an enormous amount of sonar camera footage (not shown here) has been taken along near-shore shallow areas that did not show significant rearing utilization.] After viewing each video, stop or click “cancel” on the YouTube player to allow viewing of subsequent videos in this blog entry. For the sonar camera footage, juvenile Chinook can be discerned by largely maintaining their positions in the current, exhibiting visible swimming movements. Ensonified objects moving with the current are debris drifting downstream (e.g., algae and weed fragments).

- A school of winter-run Chinook fry rearing on the riverbed adjacent to an Interstate-5 bridge pier and woody debris in the Sacramento River at water depths of 10 feet: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BP_szST5REo&NR=1

- School of juvenile Chinook salmon rearing behind a Lake Redding bridge pier in the Sacramento River at water depths approximately 10 feet deep: https://youtu.be/g0dFA8V4-sc

- School of juvenile Chinook salmon rearing in the Sacramento River in very deep water alongside a vertical bedrock wall and behind woody debris and filamentous algae or weeds: https://youtu.be/Tv0TtOCdzNY

- School of juvenile Chinook salmon rearing in the Sacramento River behind the remnants of a concrete bridge pier on the riverbed in water depths approximately 12 feet deep with a large fish swimming through the school: https://youtu.be/uAT9Wkx-nSY

An action identified in the 2014 National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) Salmon Recovery Plan is: “Using an adaptive management approach and pilot studies, determine if instream habitat for juvenile salmon is limiting salmonid populations, by placing juvenile rearing-enhancement structures in the Sacramento River.” Evaluation of such measures is also a priority in the USFWS Anadromous Fish Restoration Program (USFWS 2001). Most recently, NMFS (2016) identified “a lack of suitable rearing habitat in the Sacramento River” as an “important threat” to winter-run Chinook. Therefore, a proposal to place rearing habitat structures in some deeper-water areas (approximately > 8 feet) of the main-stem upper Sacramento River was recently developed. Using guidance from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (CDFW) Stream Habitat Restoration Manual (CDFW 2010), woody debris heavily anchored to the riverbed using large, angular boulders has been recommended for this initial step and has received favorable response from the fishery resource agencies. Angular boulders would provide the dual benefits of firmly securing woody debris and providing velocity refugia for young salmon; woody debris would provide predator refugia.

It is important to emphasize that this proposal is a pilot project and not intended to create nearshore, shallow-water habitat attributes similar to those that existed in upstream areas prior to dam construction or were lost in downstream riparian areas afterwards. There are already separate plans to construct small, shallow-water side channels in the main-stem river to address that issue. In contrast, this project is intended to place structures in completely different rearing habitat zones in deeper water where large numbers of young salmon have been observed. Given the ecological realities of the specific and unique environmental conditions in the upper Sacramento River, deep-water rearing habitats could very well be one of the most important environmental variables affecting the survival of main-stem spawning salmon progeny. If the pilot project determines high rearing utilization, the project could easily be expanded.

Sites chosen for rearing habitat placement should be in the vicinity and downstream of known spawning sites that are currently lack good rearing habitats. To provide the most benefit to young salmon, placement of rearing structures is focused on the approximate 12-mile reach of the upper Sacramento River below Keswick Dam. This area is where nearly all the endangered winter-run Chinook have been spawning in recent years and also supports the other three Chinook runs as well as the threatened steelhead.

Hopefully, a pilot project will be implemented in early 2017 … stay tuned.

Literature Cited

California Department of Fish and Wildlife. 2010. California Salmonid Stream Habitat Restoration Manual. July 2010. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/fish/Resources/HabitatManual.asp

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2014. Recovery plan for the Evolutionarily Significant Units of Sacramento River winter-run Chinook salmon and Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon and the Distinct Population Segment of California Central Valley steelhead. California Central Valley Area Office. July 2014. 406 p. http://www.westcoast.fisheries.noaa.gov/publications/recovery_planning/salmon_steelhead /domains/california_central_valley/final_recovery_plan_07-11-2014.pdf

NMFS. 2016. Species in the Spotlight. Priority Actions: 2016 – 2020. Sacramento River Winter-Run Chinook Salmon, Oncorhynchus tshawytscha. 16 p.

http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/stories/2016/02/docs/sacramento_winter_run_chinook _salmon_spotlight_species_5_year_action_plan_final_web.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1995. Working paper: habitat restoration actions to double natural production of anadromous fish in the Central Valley of California. Volume 1. May 9, 1995. Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the direction of the Anadromous Fish Restoration Program Core Group. Stockton, CA. https://www.fws.gov/lodi/anadromous_fish_restoration/documents/WorkingPaper_v1.pdf

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2001. Final Restoration Plan for the Anadromous Fish Restoration Program. A plan to increase natural production of anadromous fish in the Central Valley of California. Released as a revised draft on May 30, 1997 and adopted as final on January 9, 2001. 106 p. plus appendices. https://www.fws.gov/cno/fisheries/CAMP/Documents/Final_Restoration_Plan_for_the_AFRP.pdf

Vogel, D.A. 2011. Insights into the problems, progress, and potential solutions for Sacramento River basin native anadromous fish restoration. Report prepared for the Northern California Water Association and Sacramento Valley Water Users. Natural Resource Scientists, Inc. April 2011. 154 p. http://www.norcalwater.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/vogel-final-report-apr2011.pdf