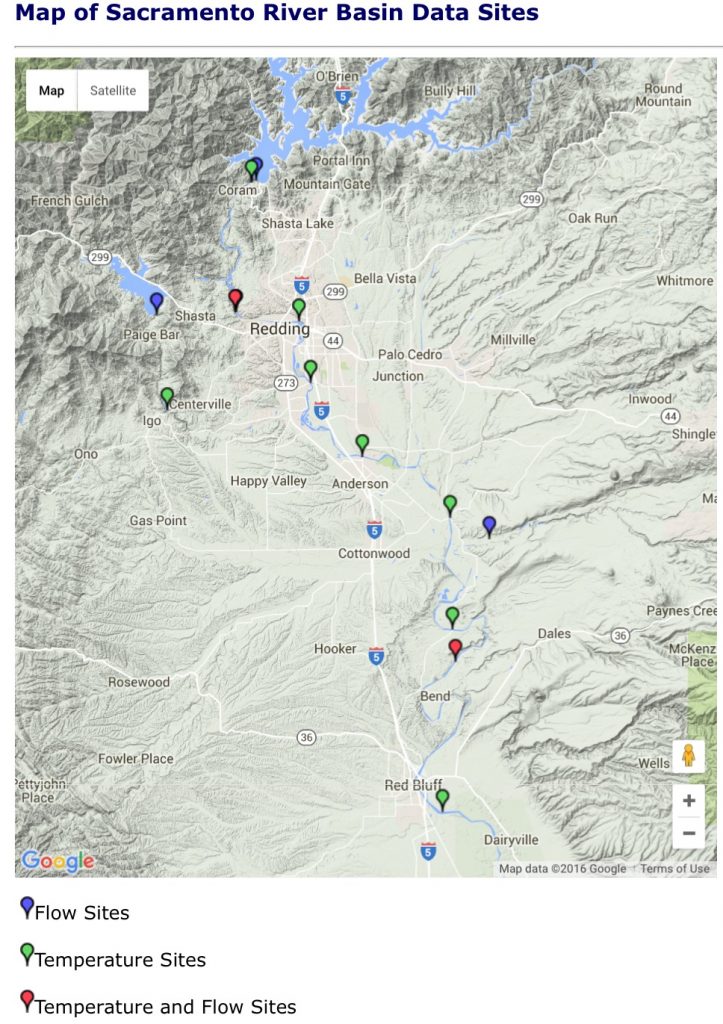

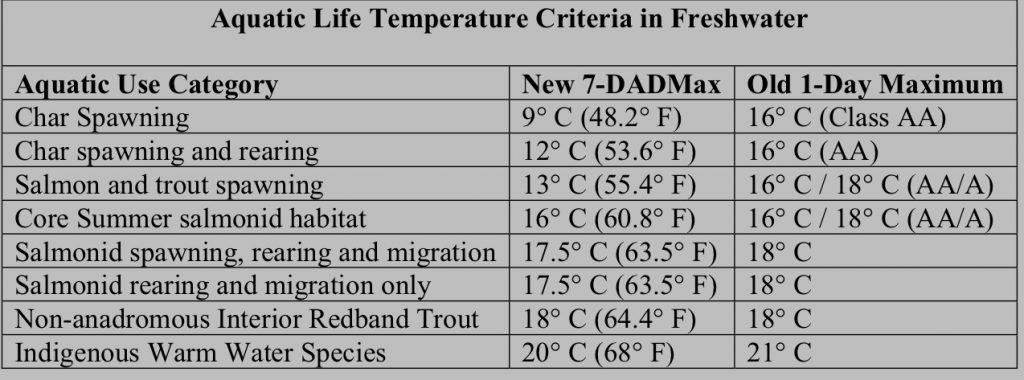

Over the past month I related water issues involving Delta and longfin smelt, striped bass, green and white sturgeon, and winter-run and spring-run salmon. All of these species need river flow and cooler water over the next several months. Shasta releases to the upper Sacramento River need to be cold, stable, and sufficient to sustain winter-run salmon eggs in the river near Redding and to sustain moderate flows and cooler water temperatures for 200 miles of river to protect sturgeon and other lifestages of salmon. Sufficient flows needs to pass through the Delta to keep the low salinity zone downstream of the Delta in the cool waters of eastern Suisun Bay, away from Delta exports.

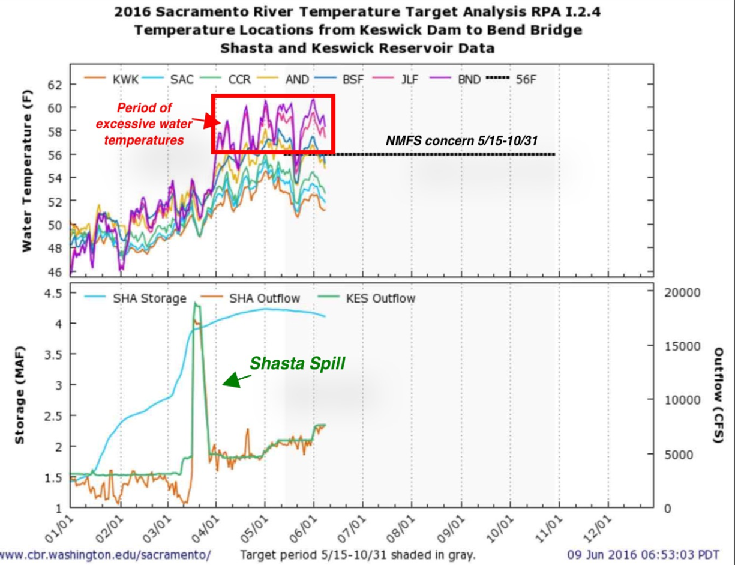

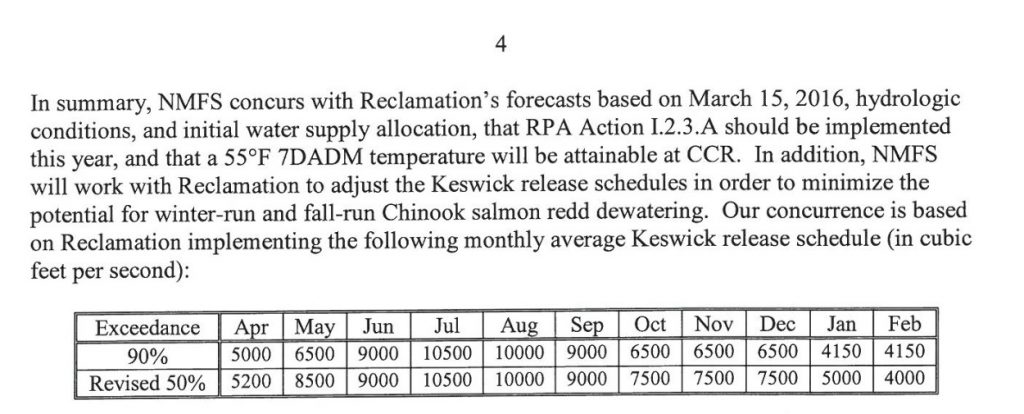

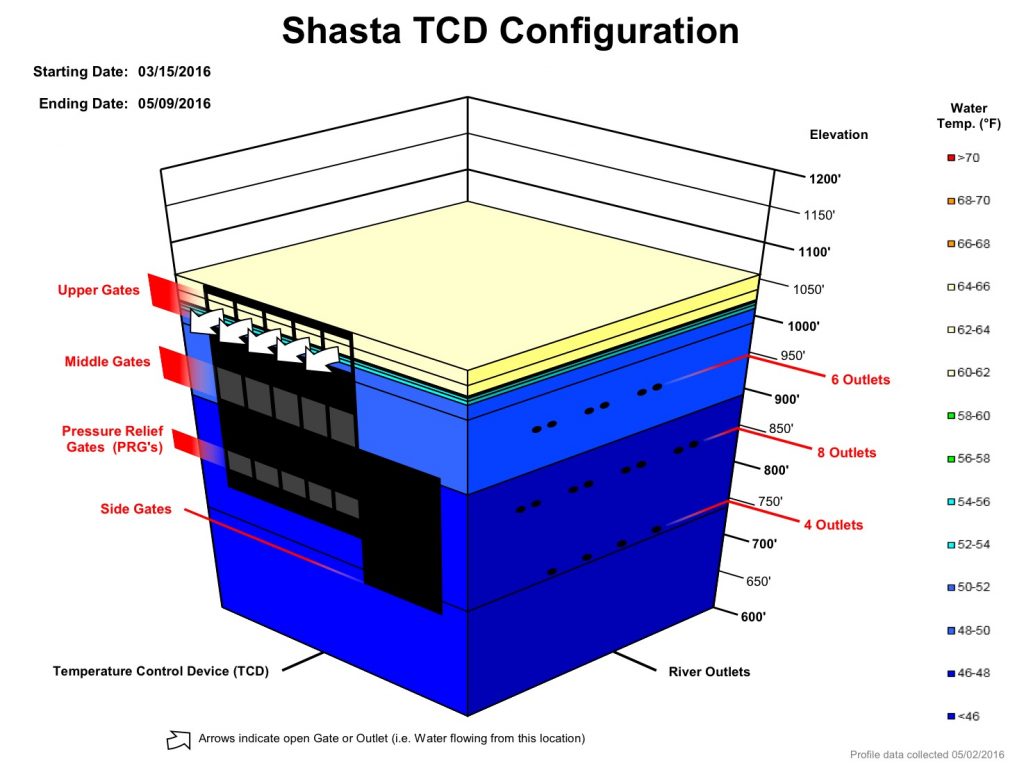

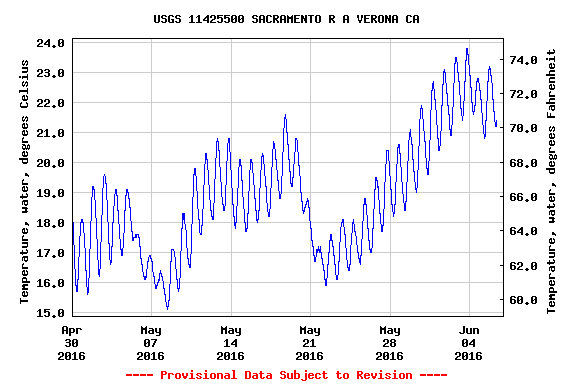

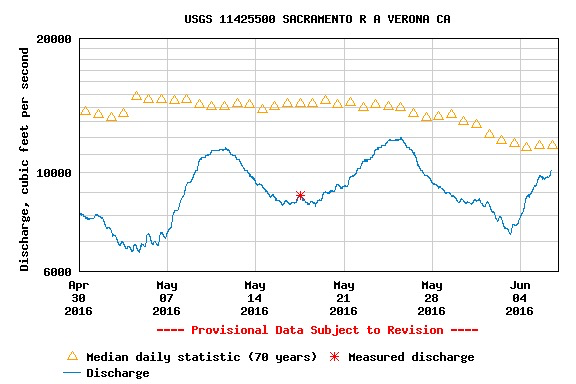

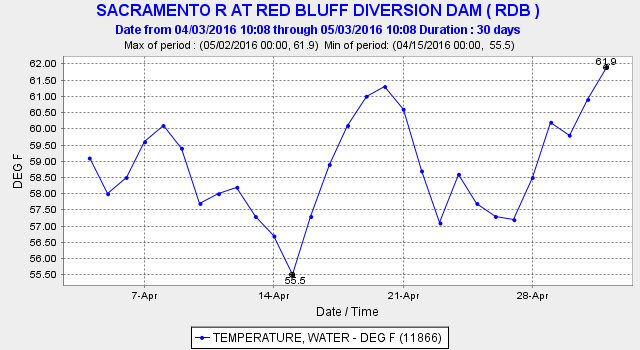

Shasta releases are now 8000 cfs, with Bend Bridge water temperature near the Red Bluff target of 56°F. In June and July of drought years 2012 and 2013, releases were 11,000-14,000 cfs. However, concern over carryover storage and sustaining cold-water releases through summer has led to a more conservative management strategy in 2016. The cold-water pool in Shasta Reservoir is being rationed to make it through the summer. Flows will rise over the next six weeks to 9,000 or 10,000 cfs to satisfy irrigation demands in the upper river.

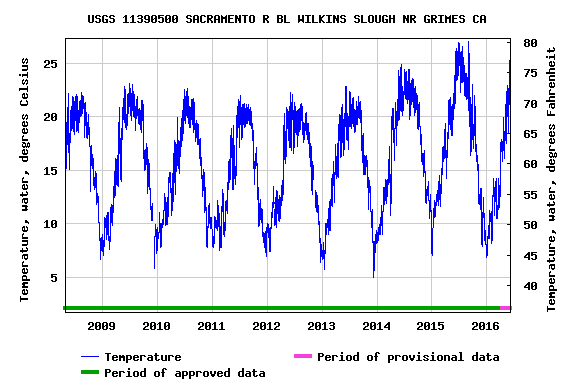

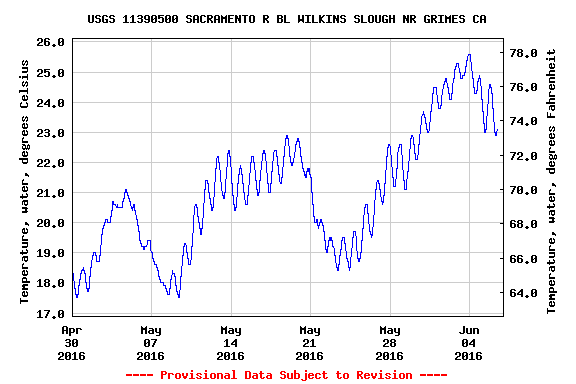

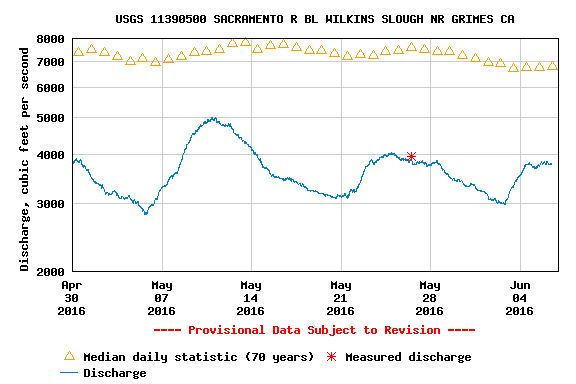

Flows in the lower Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough need to be greater than 5000 cfs in summer, if only to keep water temperature down closer to the Basin Plan’s 68°F. Flows are now 3000-4000 cfs, with water temperatures up to 75°F. In dry years 2012 and 2013, flows at Wilkins Slough were 6000-9000 cfs, and water temperatures were cooler, as some of Shasta’s storage was allocated for Delta export. This year’s management strategy to hold back Shasta releases will, if continued, keep both Wilkins Slough flows and Delta exports down.

Delta outflows need to be sustained near 10,000 cfs to keep the low salinity zone and X2 (2 ppt salinity) near Collinsville in eastern Suisun Bay. However, July outflow to the Bay required by water quality standards will be only about 8000 cfs. To help save the last of the two smelt species, 10,000 cfs would be far better.

A reasonable solution is apparent: raise Shasta releases through most of the summer by 2000 cfs to 10,000-12,000 cfs and require that the extra release be passed down the river to and through the Delta. While such a management strategy would benefit the fish, it would decrease Shasta storage by 120,000 acre-ft of water per month. At present, Shasta is 90% full at 4.1 million acre-feet (the cold-water pool volume is about 2.4 maf). At 12,000 cfs, the total Shasta release would rise to 600,000 acre-feet per month, which is about the current total release from Oroville (Feather River) and Folsom (American River) reservoirs. NMFS and USBR have determined that a 10,000 cfs Shasta cold-water release can be sustained through the summer, while a 12,000 cfs release could be problematic. Protests would no doubt come from water users who would want the extra 2000 cfs. But note that of the 20,000 cfs being released today from the three main Sacramento Valley reservoirs, only 8000 cfs is reaching the Bay.1

This solution of raising total reservoir releases to 22,000-24,000 and Bay outflow to 10,000 cfs is reasonable to help the fish after four years of drought. In 2014-2015, water quality standards were drastically reduced, with catastrophic effects to fish. The continuing legacy of these catastrophic effects creates the urgency to do better in 2016.

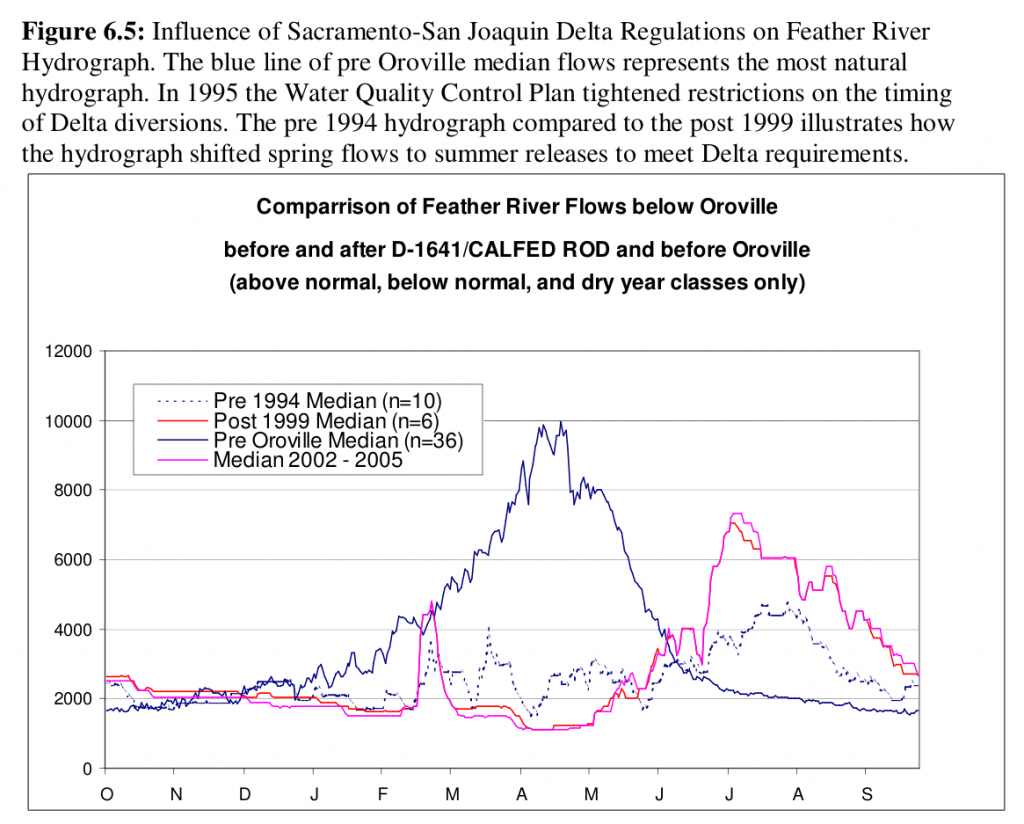

If higher releases from Shasta become problematic for whatever reason, then some compromise should be achievable, noting that water deliveries of Shasta water are to be provided only after the needs of the fish are first considered, including conservation of Shasta’s cold-water pool through the summer and early fall (Water Rights Orders 90-05 and 92-02). Further, Central Valley water rights are provided via the Trinity River trans-basin diversion to Keswick Reservoir on the Sacramento River below Shasta Dam, but the Trinity supply is much in doubt because Trinity storage has failed to recover after the drought, unlike Shasta storage. A lack of Trinity supply this summer will further limit water available for irrigation in the Central Valley. Yet another constraint is whether the available storage in Oroville and Folsom reservoirs is able to satisfy Delta demands without compromising the needs of endangered fish in the Feather and American rivers.

Sorting out these conflicts and needs is the responsibility of the State Water Resources Control Board. The Board’s top priority should be the basic needs of the endangered salmon, sturgeon, and smelts of the Central Valley. At minimum, the Board should require the following conditions this summer:

- Below Shasta – Stable flows of 9,000 to 10,000 cfs and 56°F average daily water temperatures near Red Bluff (Jellys Ferry or Bend Bridge).

- Lower Sacramento River – minimum 5000 cfs at Wilkins Slough (RM 125 on the Sacramento River)

- Delta Outflow – 9,000 cfs in July, 5,000 cfs in August, and 4,000 cfs in September.

- A further complication is that South Delta export criteria allow an increase from 35% of inflow to 65% starting July 1. Exports in June are limited to 5000 cfs. In July, exports can be raised to 65% of inflow, but only if outflow is kept at 8000 cfs. Delta ag diversions are also near 4000 cfs. Thus July Delta inflow of 20,000 cfs or more (compared to the present inflow of 15,000 cfs) would be needed to allow 10,000 cfs of Delta export. ↩