Water transfers are allowed through the Delta under federal biological opinions during the summer, but in 2015 the period was extended through the fall by the State Water Board, with the approval of the federal fisheries agencies responsible for administering the Endangered Species Act (ESA). There are many types of water transfers, but I am referring specifically here to transfers of federal Shasta-Trinity storage through the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta to state and federal water contractors south of the Delta. Water released from Trinity and Shasta reservoir storage is passed down the Sacramento River into the Delta where it is exported in the south Delta and then delivered to south-of-Delta water contractors (who purchased the water from northern California contractors who have priority on the Shasta-Trinity water). This was the largest component of water transfers in the Central Valley in 2015.

This week, the Delta Stewardship Council held a workshop on these transfers through the Delta. The Council concluded: “On the issue of single-year water transfers and whether they impacted the coequal goals and therefore should be subject to the Delta Plan’s covered action process, the Council did not feel they had all the information they needed, so a determination was made to exempt single-year transfers from the covered action process until December 31, 2016, and a request made for further information.” 1In other words, the Council decided it needs more information before it can support these single-year water transfers.

At the workshop, DWR’s representative Bill Croyle stated: “2014 was a banner year. People needed the water, there was a little bit more water in the system, it was the third year of a drought, and I think the water transfer system, the market, the experience, the education, and some new tools and also a high level of involvement as necessary from the executive offices of all of our agencies resulted in over 400,000 acre-feet of water being moved to where it was really needed.”

Tom Howard, Executive Director of the State Water Board stated: “Really the concern is in the Delta, and then the question becomes how do you protect Delta resources. The way the water board has been looking at it is if you are meeting all your Delta objectives, then that’s what the water board at least at one time considered adequate to protect public trust resources. We’re in the process of taking another look at that because there have been a lot of issues associated with the existing standards potentially. Also when we did the modeling for a lot of the development of these standards 20 years ago, we didn’t throw a lot of transfers in, so here we are throwing 500,000 – 700,000 acre-feet of transfers or more in a period in a four month period so as we work to update the Bay Delta plan, we will be assuming a large transfer load into the system as well beyond just operation of the projects and how they move water.”

DWR’s Jerry Johns stated: “The Bureau when they did their EIR on long-term water transfers, they also evaluated these impacts and came to the conclusion that there wouldn’t be significant impacts, so I think it has been evaluated in a pretty robust fashion.”

Representing the fish, Bruce Herbold, retired EPA biologist, offered: “So my recommendations on single year transfers is just don’t do them….We’ll have more water in storage upstream, we will have less streamflow modifications, and we’ll have less exports out of the Delta in each year.”2

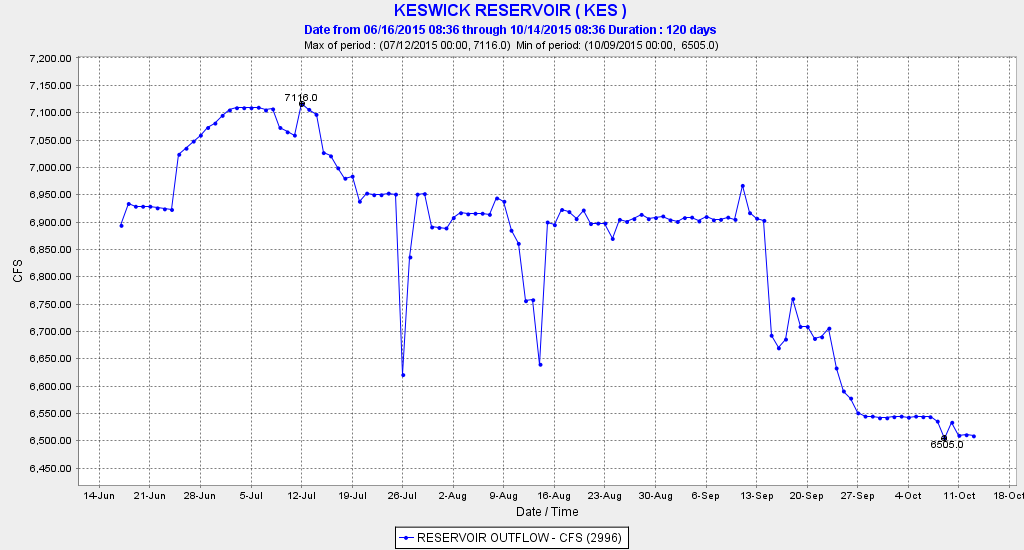

I agree with Dr. Herbold. The big impact is in the loss of Shasta-Trinity storage, which can be seen in the release of Keswick Reservoir water to the Sacramento River near Redding in the figure below.

Sacramento River releases recommended in the 2015 Salmon Plan developed by the State Water Board, fisheries agencies and the Bureau of Reclamation called for 6000 cfs for September and 5500 cfs for October. The 500-1000 cfs extra in September and 1000 cfs extra in October amount to approximately 80 TAF of “extra” storage releases that have gone to transfers so far this year in just six weeks.

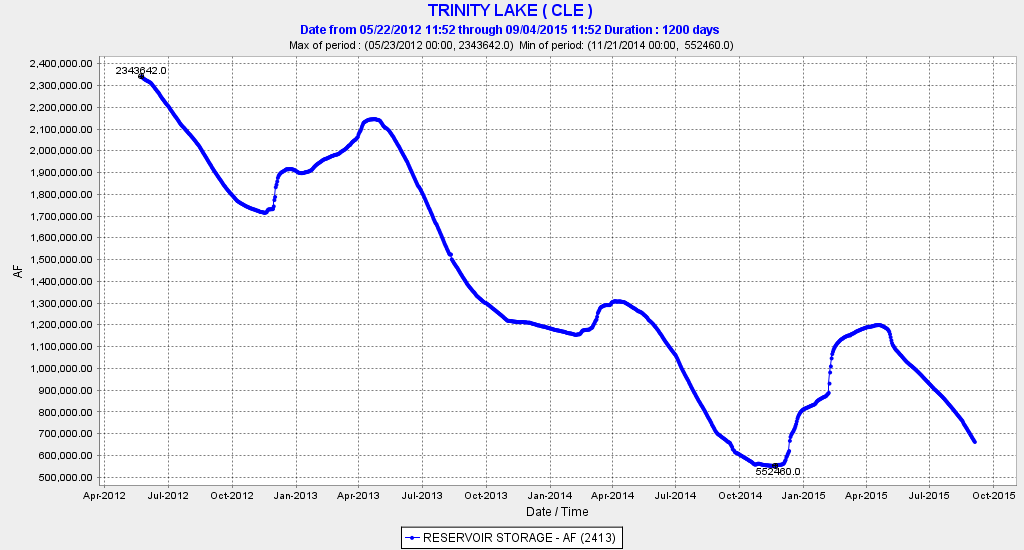

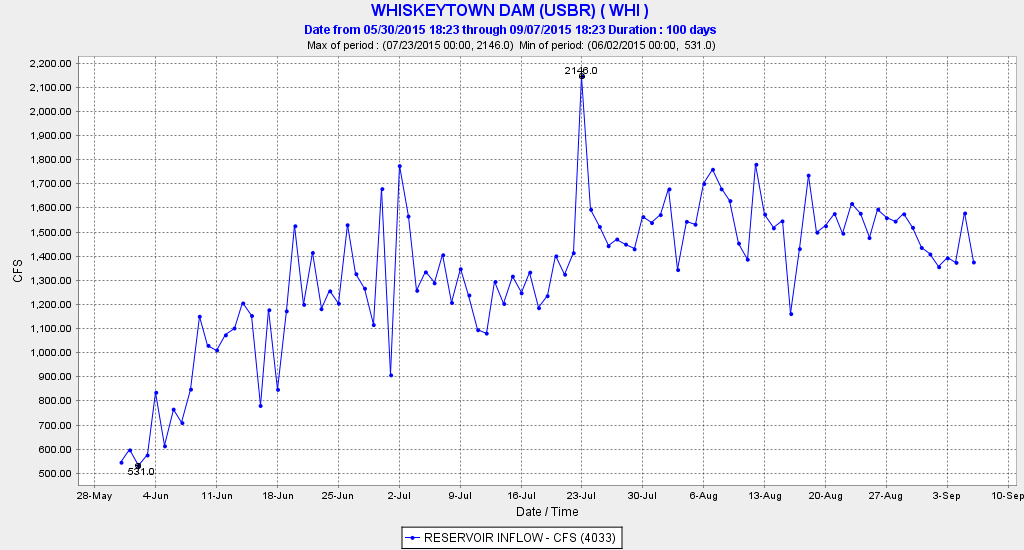

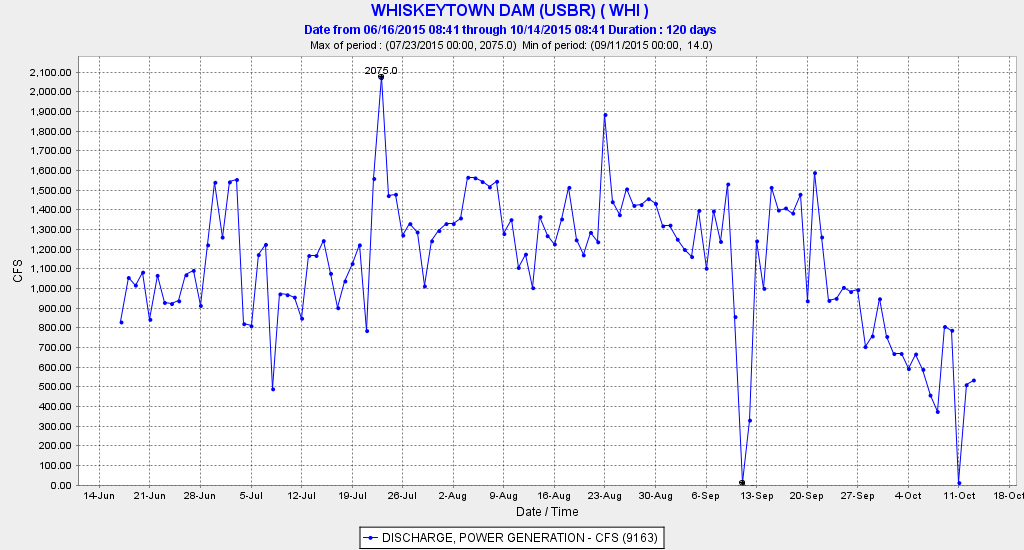

The diversion from the Trinity River as seen below as Whiskeytown Reservoir power releases to the Sacramento River (most to Keswick Reservoir via Spring Creek Powerhouse) amounted to approximately 80 TAF between September 1 and October 14. This water represented over 10 percent of the remaining water in Trinity Reservoir, already at critical low levels after four years of drought. This new low level is well below the critical end of year storage level needed to sustain flows through the winter and next year’s cold-water pool for Klamath-Trinity salmon.

Because Shasta’s cold-water pool has been needed over these same six weeks since September 1 (and prior to that) to cool the warm Trinity water before it is released to the Sacramento River from Keswick Reservoir, Shasta’s cold-water pool and storage has also been used for the transfers. Shasta Reservoir’s cold-water pool and storage are needed to sustain salmon through the fall, but also the entire water supply for California next year. Shasta Reservoir is now down to 1.6 MAF out of its 4.55 MAF of capacity, its lowest level since the 1991-92 and 1976-77 droughts.

Because Shasta’s cold-water pool has been needed over these same six weeks since September 1 (and prior to that) to cool the warm Trinity water before it is released to the Sacramento River from Keswick Reservoir, Shasta’s cold-water pool and storage has also been used for the transfers. Shasta Reservoir’s cold-water pool and storage are needed to sustain salmon through the fall, but also the entire water supply for California next year. Shasta Reservoir is now down to 1.6 MAF out of its 4.55 MAF of capacity, its lowest level since the 1991-92 and 1976-77 droughts.

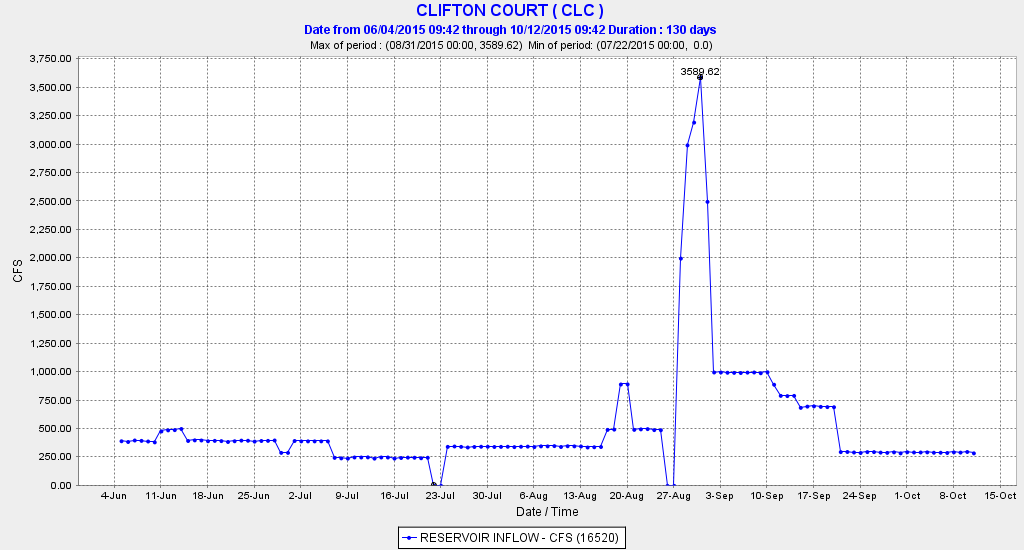

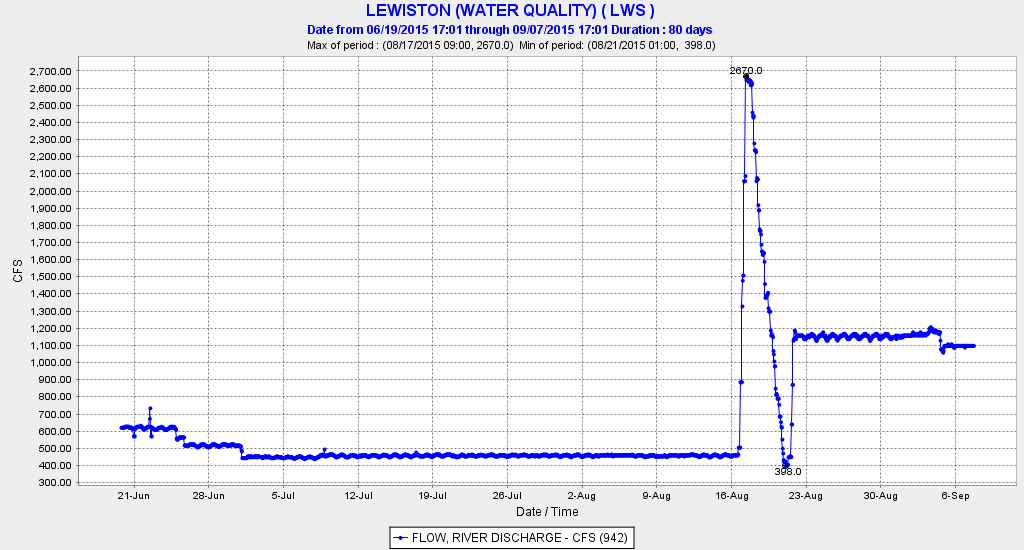

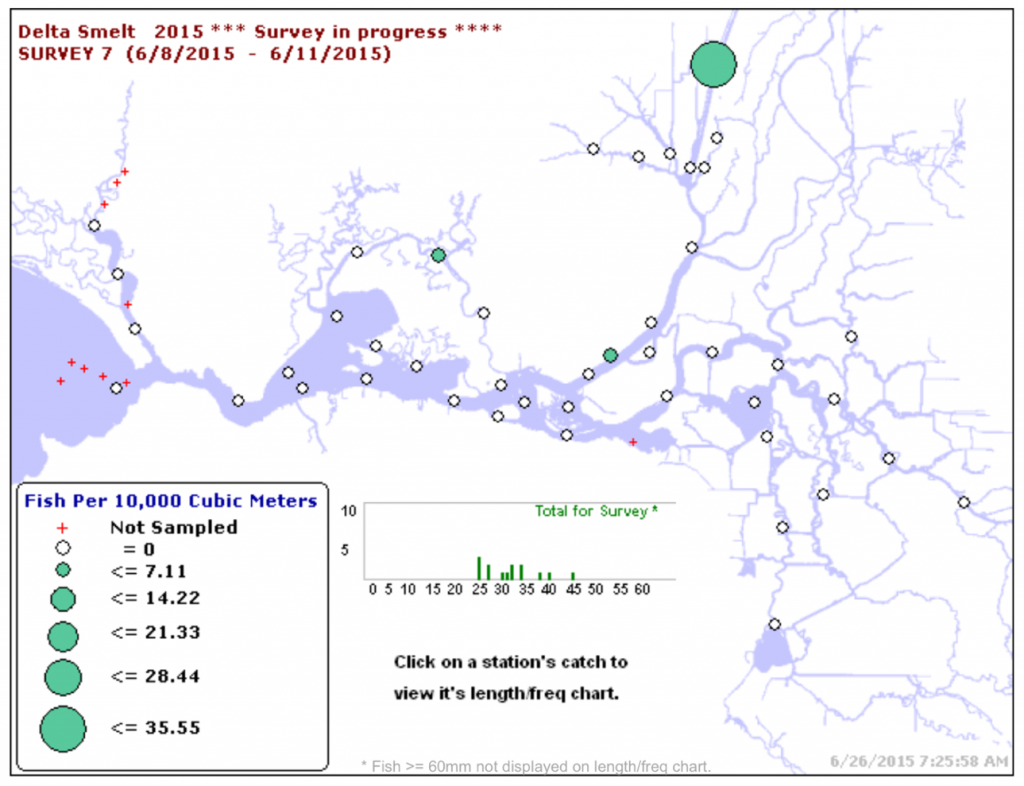

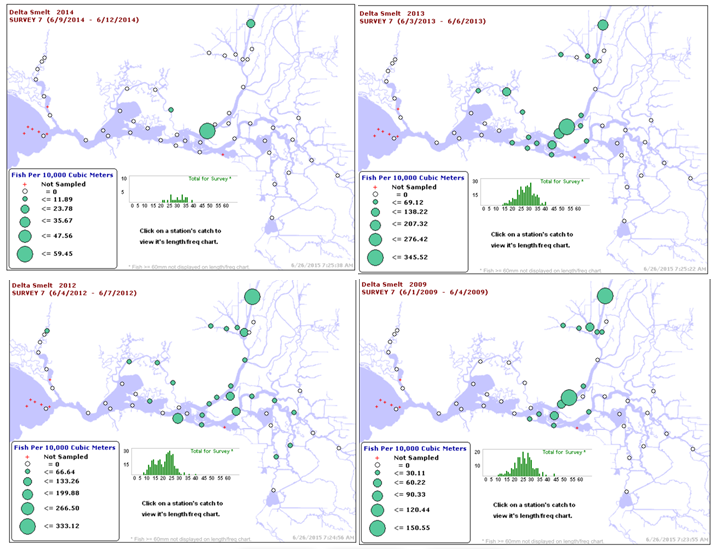

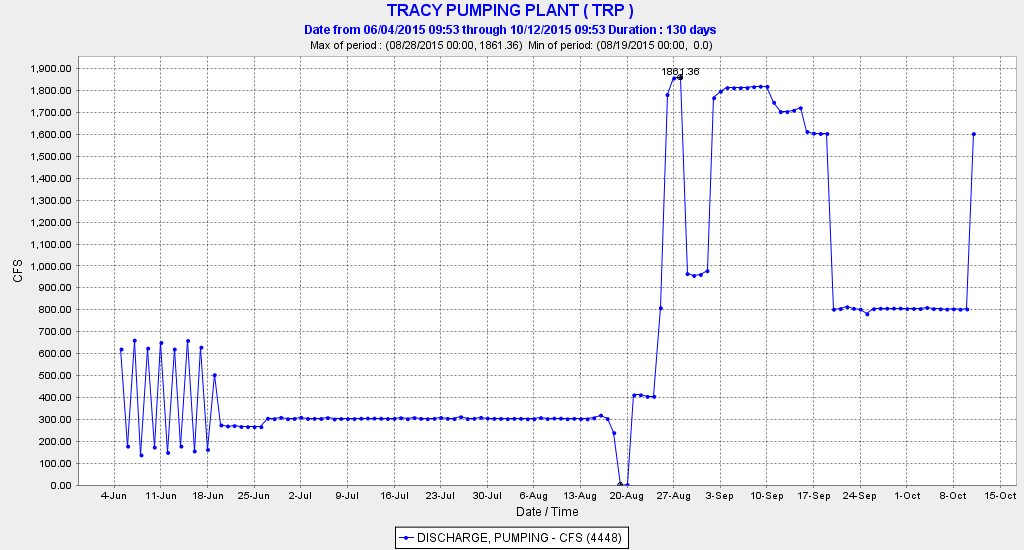

These transfers also have significant effects on the Delta and its low salinity zone critical habitat for native Delta fish species, including the Delta smelt. Delta exports are the mechanism for transferring water from the north to the south. Transfers are evident in recent Delta exports. As shown in the chart below, CVP exports increased in amounts between 600-1500 cfs in September and early October in response to CVP and other transfers. Most of the extra CVP export was sourced in Shasta and Trinity reservoirs. State Water Project transfers through the Delta also occurred (see next chart).

With flows through and out of the Delta to the Bay very low in this critical drought year, such exports have higher than normal environmental effects; however, transfers are exempt from restrictions applied to project exports Even large volumes transferred at once do not trigger additional protections from the effects of pulling more water and more fish from the Sacramento River into the central Delta. We are glad to see that Mr. Howard has at least acknowledged these impacts. During drought workshops in 2014 and 2015, CSPA objected to this free pass for transfers through the Delta for years, calling them “the phantoms of the exports.” In early 2015, Mr. Howard explicitly re-authorized their special exempt status.

CVP Exports in summer 2015. The total “extra” export is less than the total transfer by about 20 %, because some transfer water is required to pass through to the Bay as “carriage water” to repel salinity.

- http://mavensnotebook.com/2015/10/13/water-transfers-and-the-delta-plan-part-2-the-agency-view/ Additional quotes are from the same source unless otherwise noted. ↩

- http://mavensnotebook.com/2015/10/14/water-transfers-and-the-delta-plan-part-3-the-environmental-perspective/ ↩