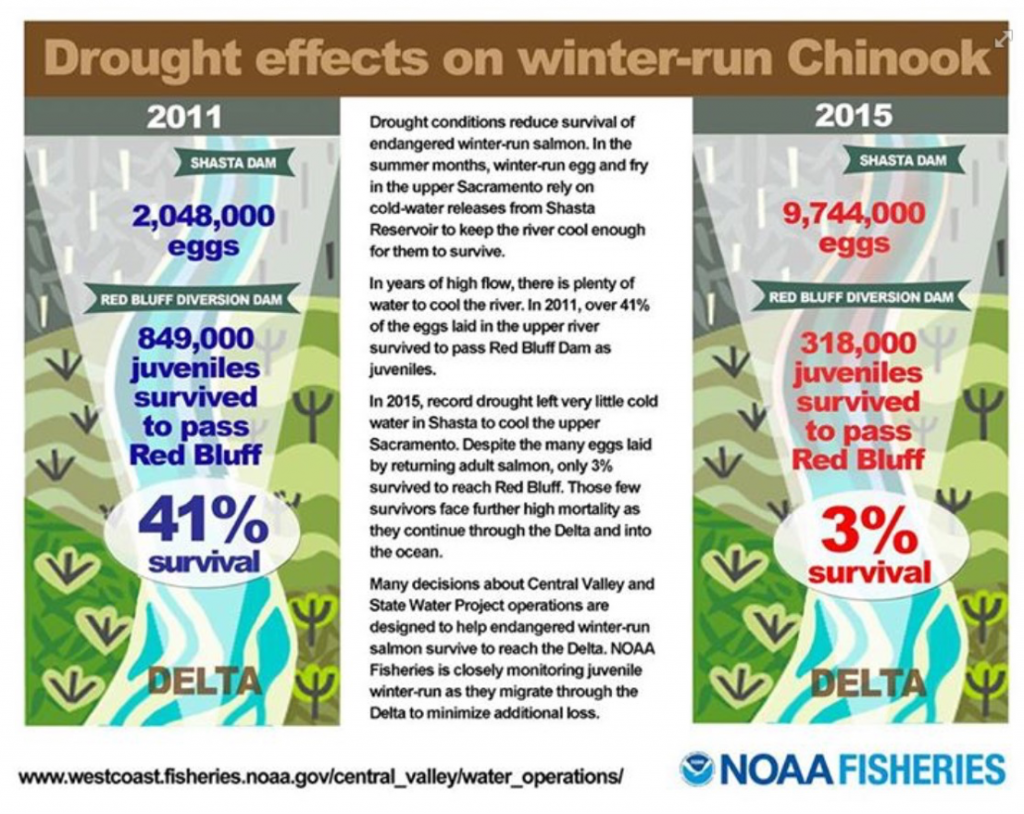

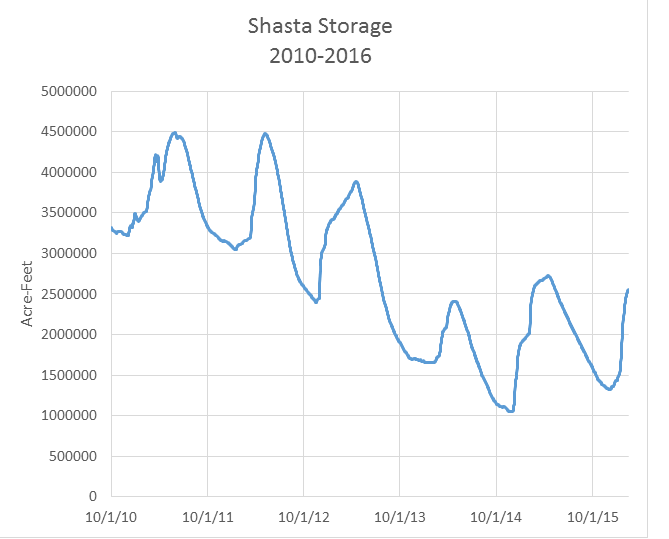

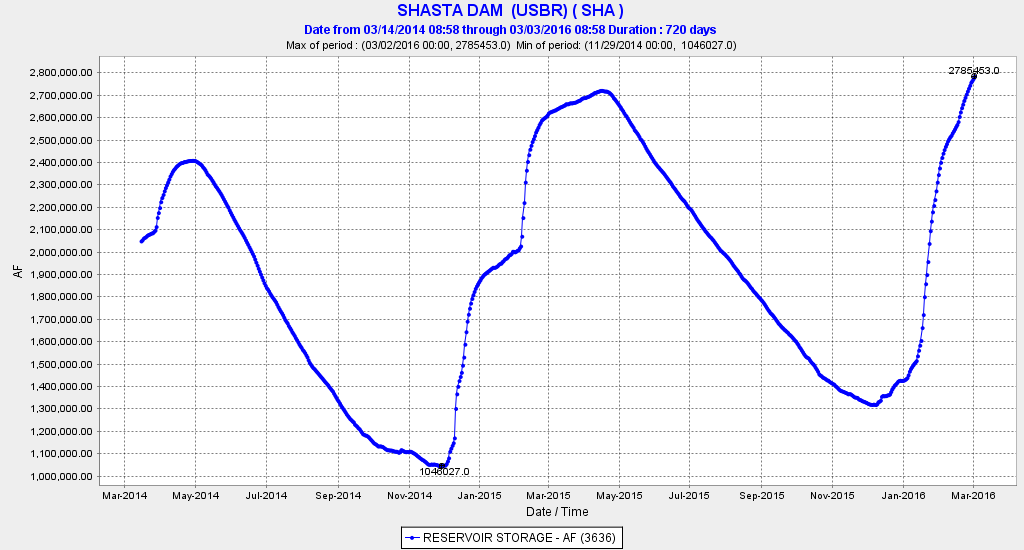

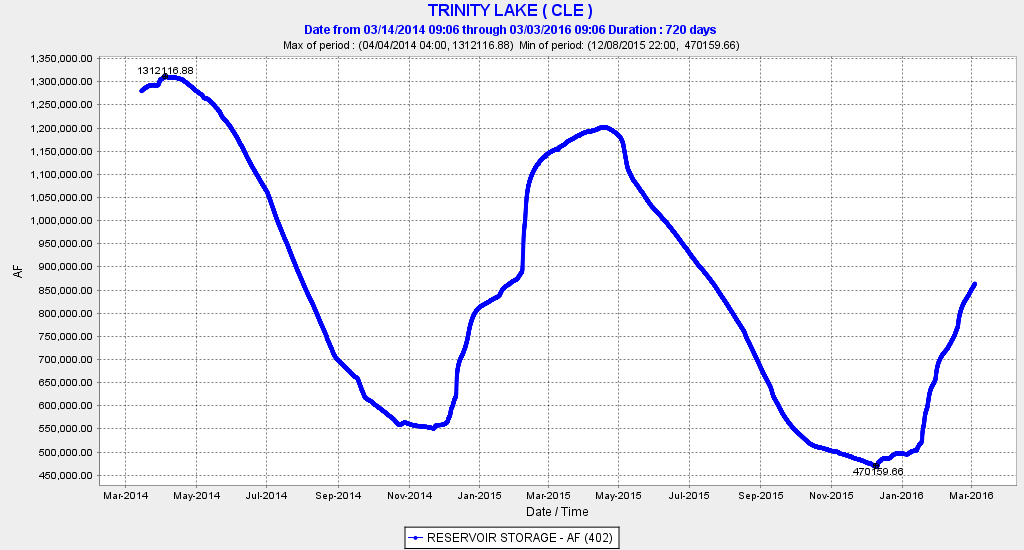

Water Year 2016 on the Sacramento River has been designated a “Below Normal” year. Water Year 2010 was also a Below Normal year. Both years followed multiyear droughts. In both years, Shasta Reservoir was nearly full at the end of April (2010 was 4.4 maf; 2016 was 4.2 maf). In early May 2010, Keswick releases were 7500 cfs, and release water temperatures were 50-52°F. In early May 2016, Keswick releases have been 5200-6200 cfs, and release water temperatures have been 53-55°F.

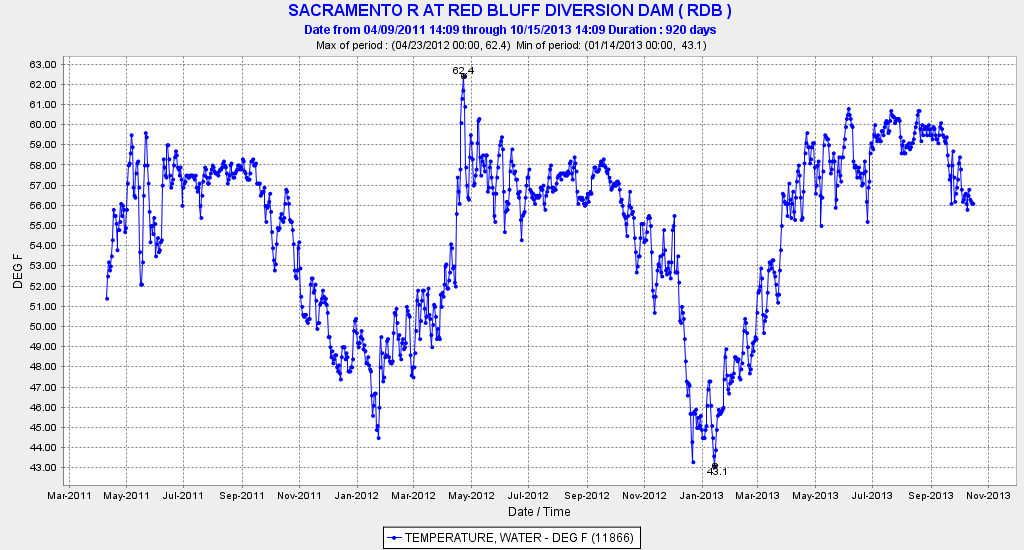

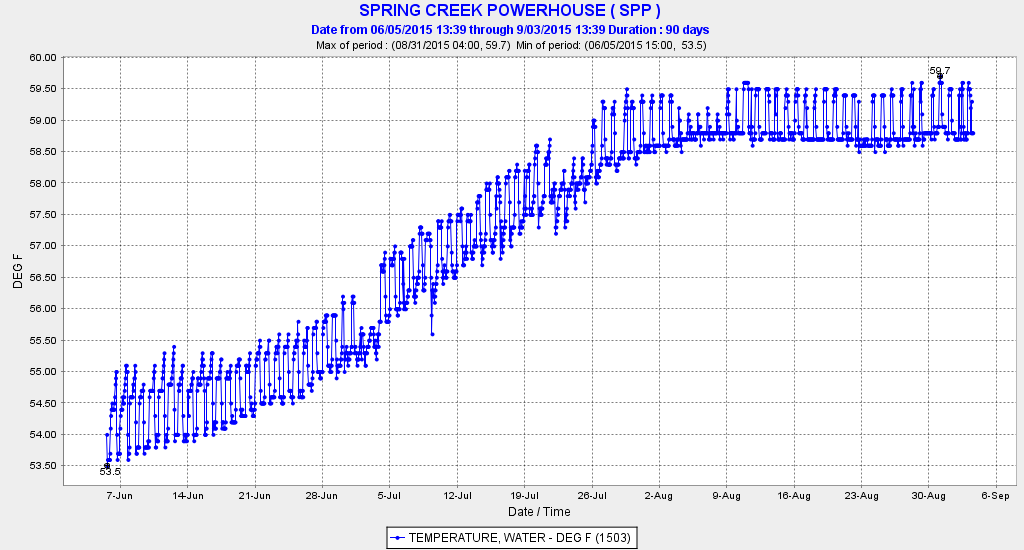

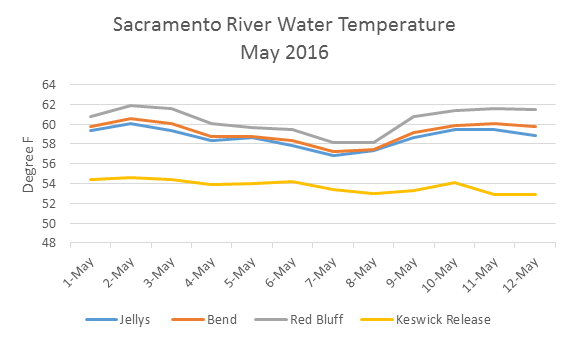

In April and May, 2010, water temperatures in the upper river remained below 56°F. In contrast, the warmer, lower flows in 2016 have led to excessively warm water temperatures in the upper Sacramento River. Water temperatures have reached 60-62°F in the upper river (Figure 1), which are well above the prescribed water quality standard of 56°F necessary to protect spawning salmon and sturgeon. Winter-run salmon began spawning in late April. Green and white sturgeon spawn in May.

Figure 1. Water temperature in the upper Sacramento River below Shasta Reservoir in early May 2016. In contrast, water temperatures at these locations during early May 2010 were 56°F or lower.

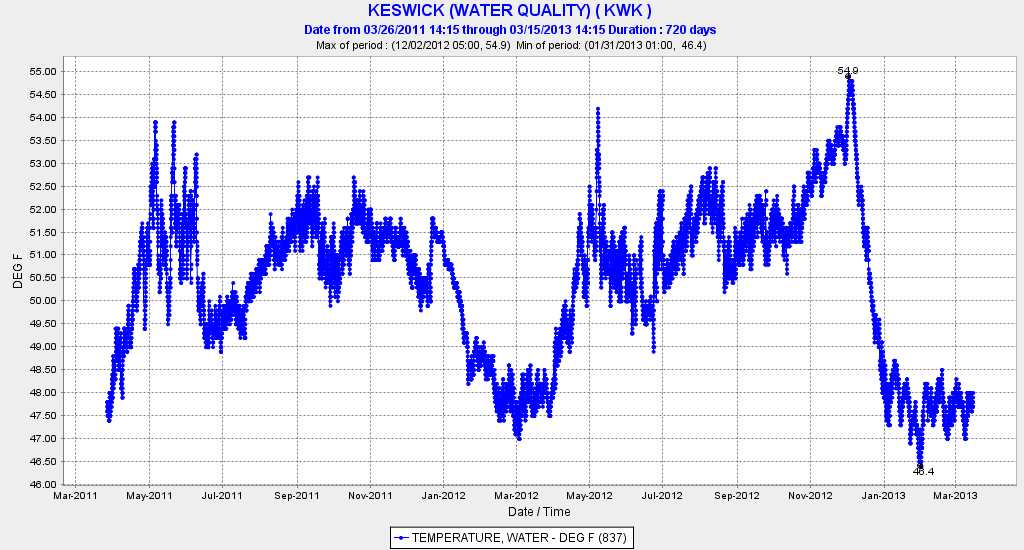

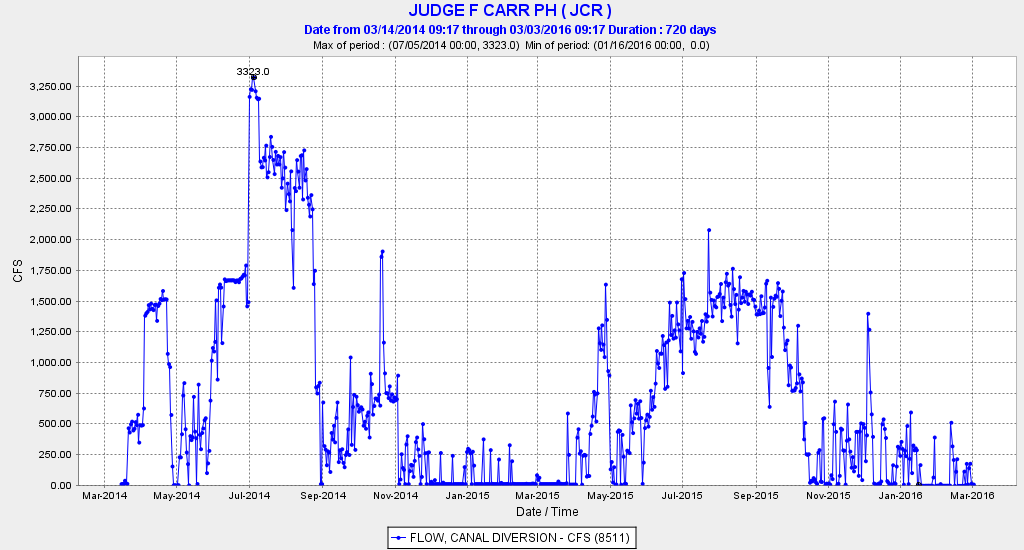

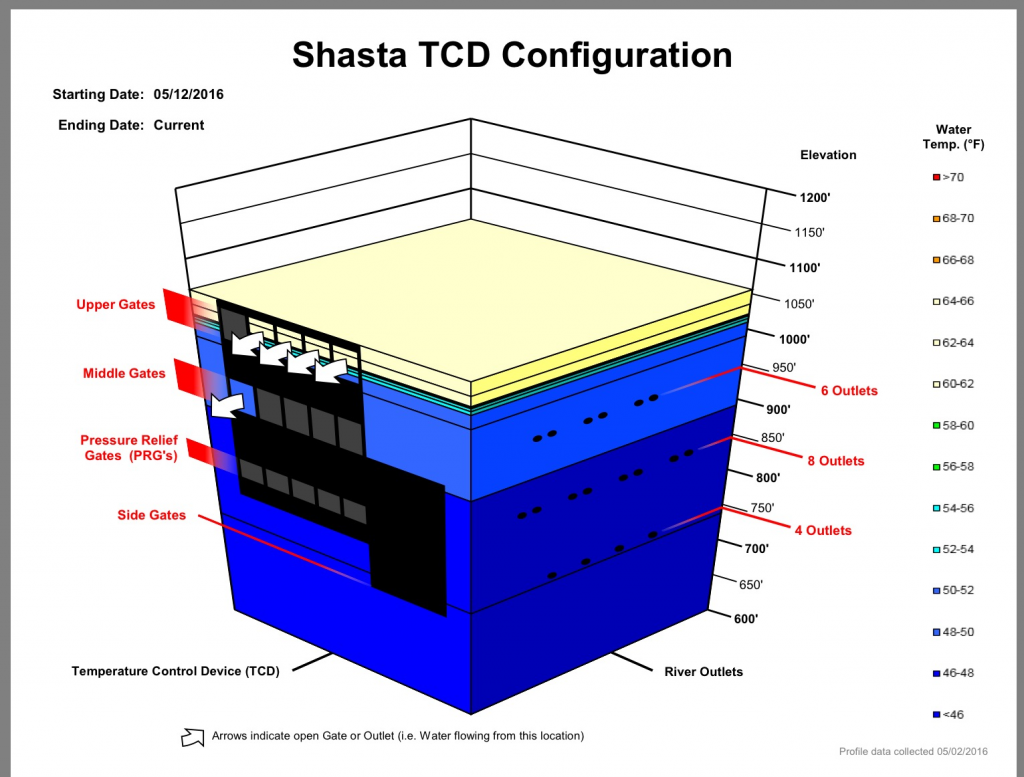

Reclamation’s CVP operations should strive to maintain the 56°F standard through the spring and summer, as prescribed in the Basin Plan and in the NMFS biological opinion for Shasta operations. This temperature can be achieved by increasing Shasta releases or by lowering the water temperature of releases using the temperature control tower/device (TCD) at the dam, or by a combination of these elements. In the last few days, Reclamation has increased releases and has added colder water, resulting in slightly colder Keswick releases (Figure 1). Reclamation has decreased the temperature of releases by opening one the six middle outlets of the Shasta Temperature Control Device (Figure 2). However, downstream temperatures remain high, because air temperatures and water diversions downstream are also increasing.

While there is some logic behind Reclamation’s decision to minimize reservoir releases to save Shasta storage, it is inappropriate to jeopardize endangered fish in the upper Sacramento River with excessively warm water this year, given the abundance of cold water in the reservoir. 1

With Shasta releases expected to increase soon to meet increasing irrigation demands, it will be imperative that water temperatures upstream of Red Bluff remain below 56°F to protect spawning salmon and sturgeon and their young into and through the summer.

The “official” temperature target and control point since April 15, 2016 have been 58°F at Redding (station CCR). In 2010, the target temperature was 56°F, and the control point was at Jellys Ferry (RM 267), 20 miles downstream of Redding. The State Board and NMFS should immediately change the target temperature to 56°F, and move the control point at least downstream to Jellys Ferry. Preferably, the compliance point should be further downstream at Red Bluff, to be in compliance with the NMFS biological opinion (56°F at Red Bluff – RM 243). The Basin Plan puts the compliance point further downstream still, (56°F at Hamilton City – RM 200). 2

Following catastrophic losses of winter-run in the Sacramento below Shasta during the past two years, it is imperative to meet the summer water temperature goals as prescribed in the NMFS biological opinion. The Shasta cold-water pool and storage available are more than adequate to meet these objectives.

Figure 2. Shasta Dam’s temperature control tower/device or TCD has multiple options for releasing water from the reservoir. One middle outlet was recently opened to reduce the temperature of the water released to the Sacramento River. (Source: USBR MidPacific Division)

- A disproportionate amount of Sacramento River Delta inflow this spring has come from Oroville Reservoir (Feather River) and Folsom Reservoir (American River) storage releases. Excessive use of Folsom storage to meet Bay-Delta needs could lead to loss of its cold-water pool this summer and greater mortality of over-summering juvenile salmon and steelhead in the American River. ↩

- A plan for summer operations from Reclamation is due by May 15, 2016 ↩