Starting with the Strawberry Moon

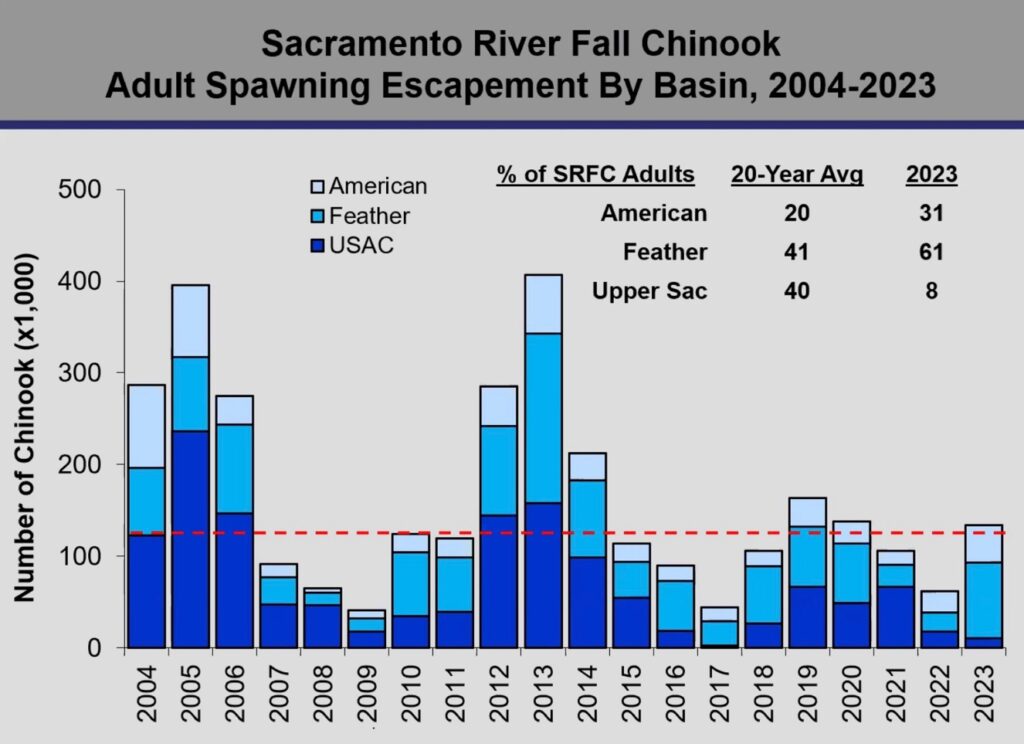

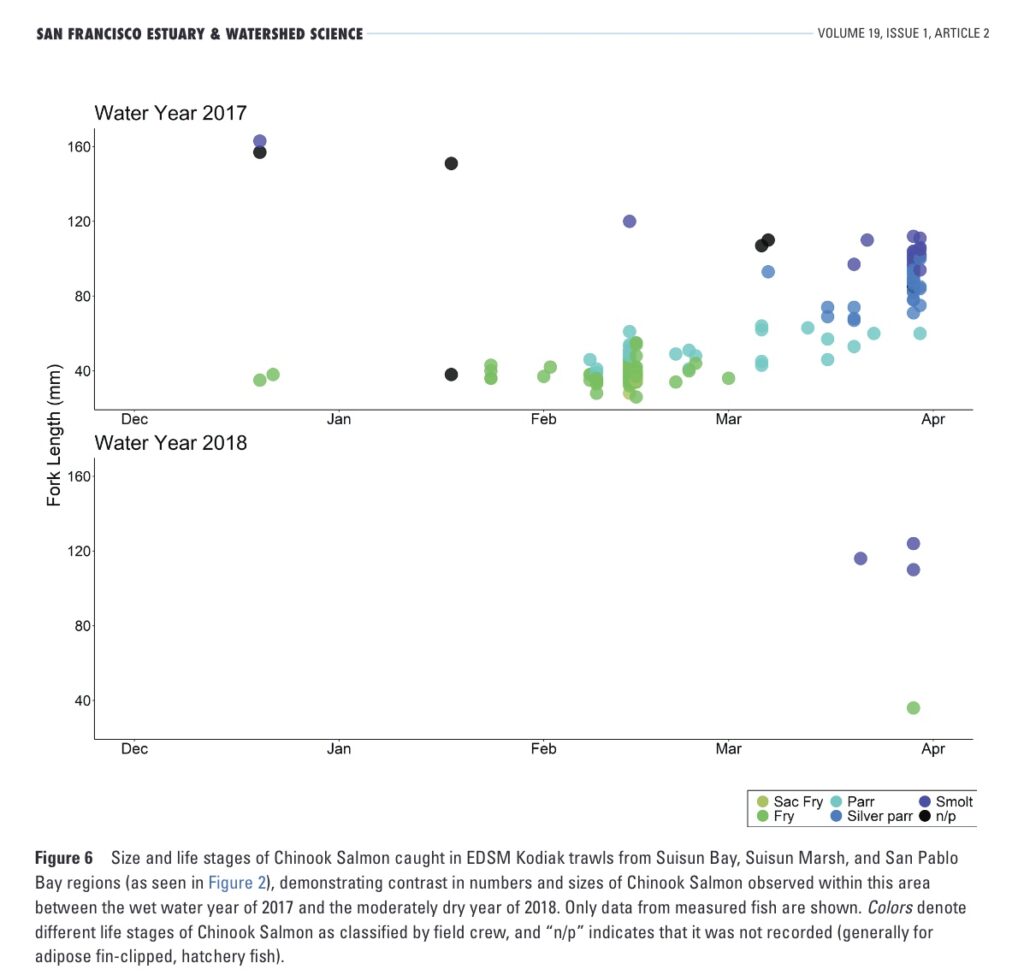

The Strawberry Moon, sometimes called the planting moon, is the June full moon (e.g., June 21, 2024). June is the end the juvenile salmon and sturgeon emigration season from the Central Valley to the Bay. The Strawberry Moon June 2024 super tides drained the warm river and Delta waters into the Bay driving the remainder of the brood year 2023 salmon and sturgeon with it toward the Bay.

In a wet year, the young salmon and sturgeon are pushing through the Delta throughout June. But 2024 was just an average water year, with the seasonal salmon and sturgeon emigration to the Bay ending with lower streamflow and higher water temperatures from the rivers through the Delta and then entering the Bay. At this point, we cannot yet determine if the seasonal event was successful – we just do not know. Regardless, we now must look toward the Bay to ensure that fish die-offs from warm water, low DO, and toxic algae blooms do not occur again.

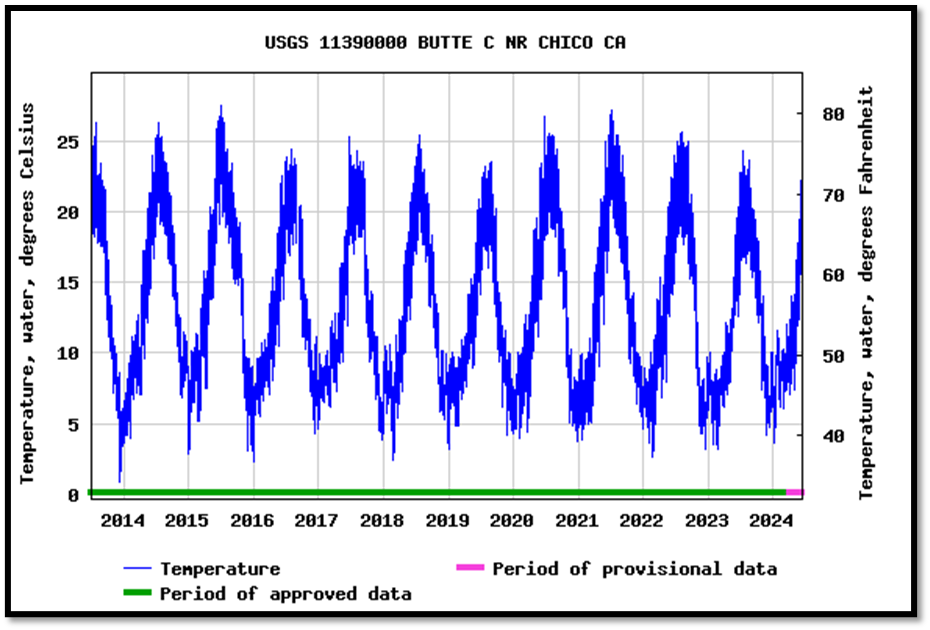

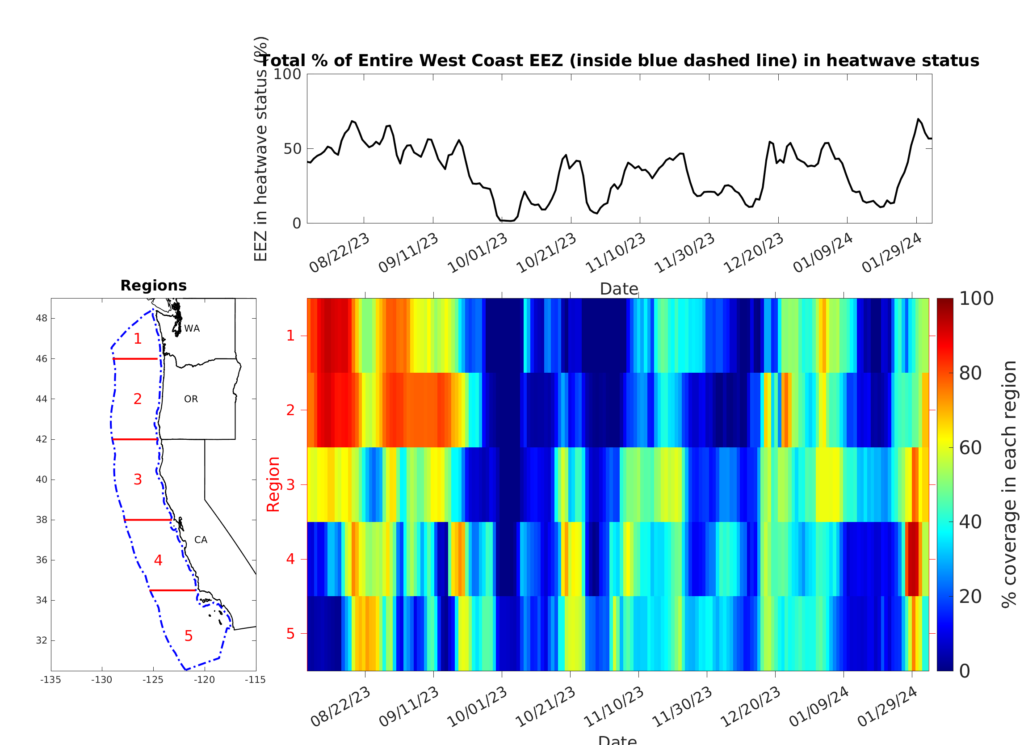

What is important now is maintaining the Bay through the summer by ensuring toxic algae blooms and warm water do not stress the salmon and sturgeon present in the Bay. With water temperatures in the eastern parts of the Bay already high (22oC/72oF) at the beginning of summer, it seems the Bay is destined for another bad summer of toxic algae blooms and dying adult sturgeon.

What can be done to help keep the Bay cool this summer? There are three actions that when taken together and in sequence can help keep the Bay cooler: Keeping the rivers cooler keeps the Delta cooler. Keeping the Delta cooler keeps the Bay cooler. There are also some Bay actions that can sustain cooler water temperatures.

- Keeping Lower Rivers Cooler

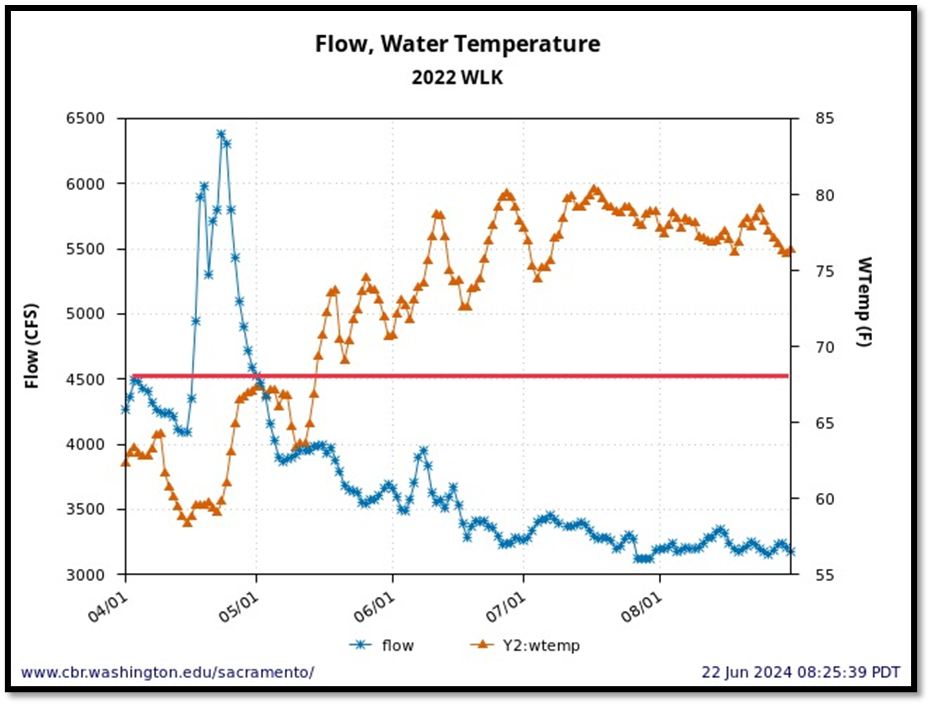

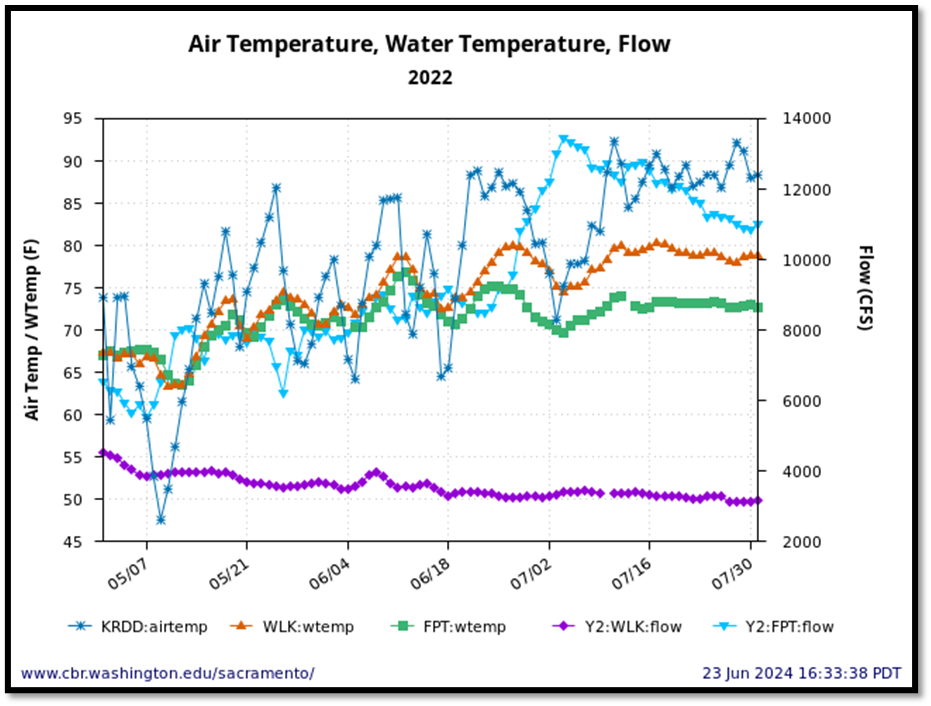

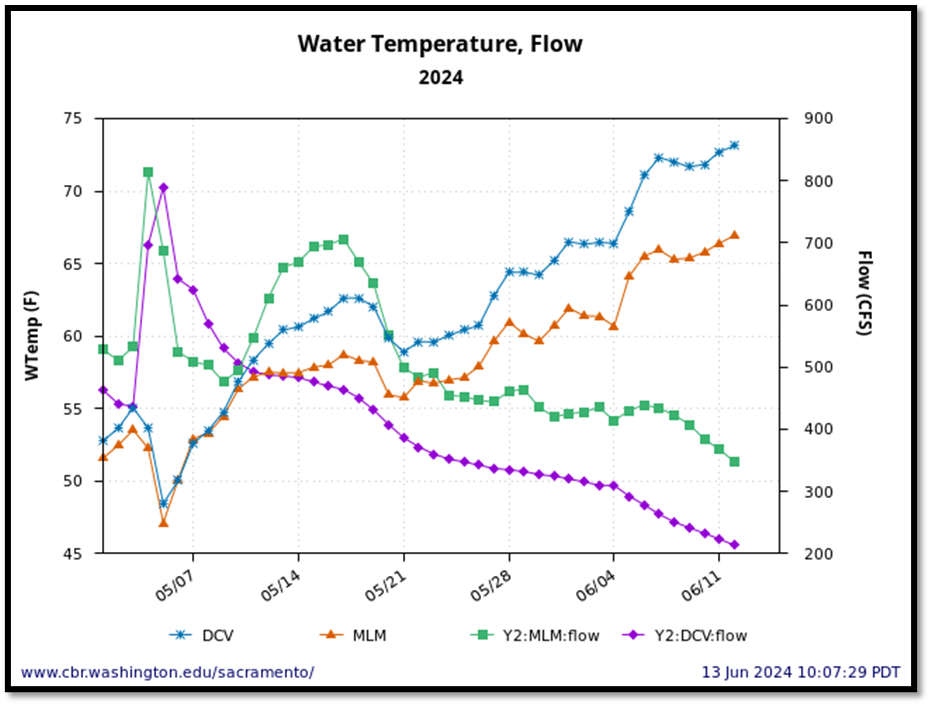

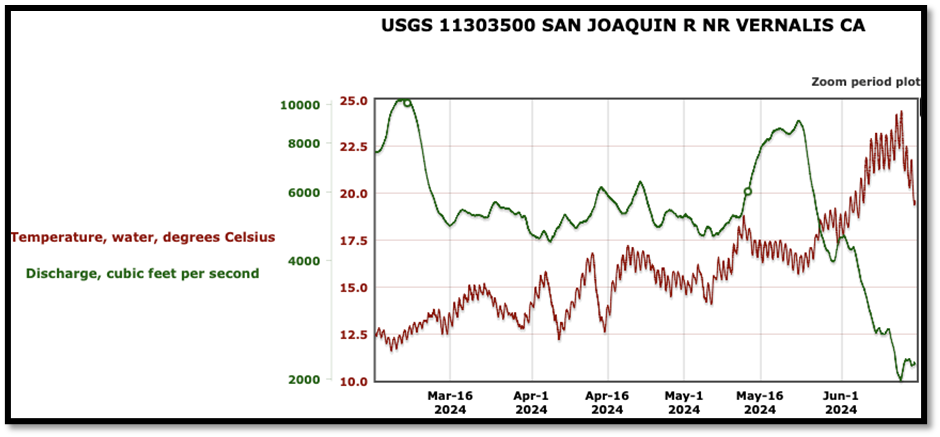

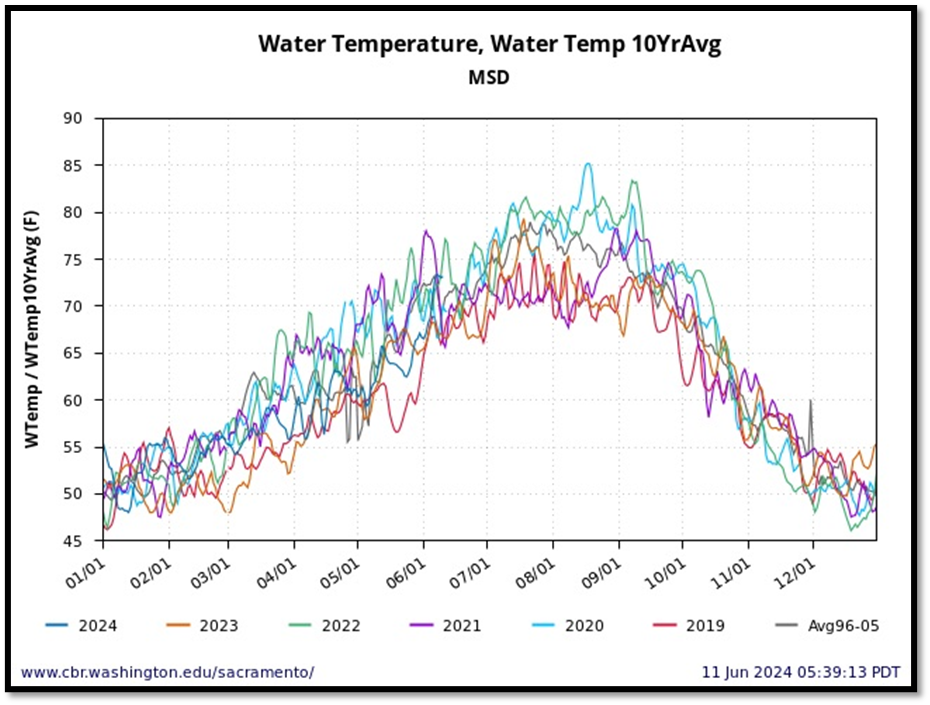

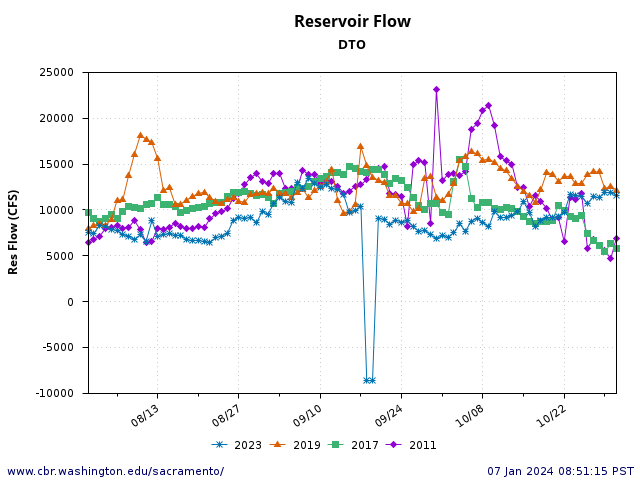

First, how to keep the lower Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers entering the Delta cooler. Higher streamflows speed the water along in the hot Valley keeping the rivers from absorbing heat. We are only talking about 5oF or so, but it is an important five degrees. That is accomplished by maintaining adequate (legally prescribed) streamflows with reservoir releases, especially during summer heat waves that are getting hotter and more frequent with each decade (i.e., climate change).

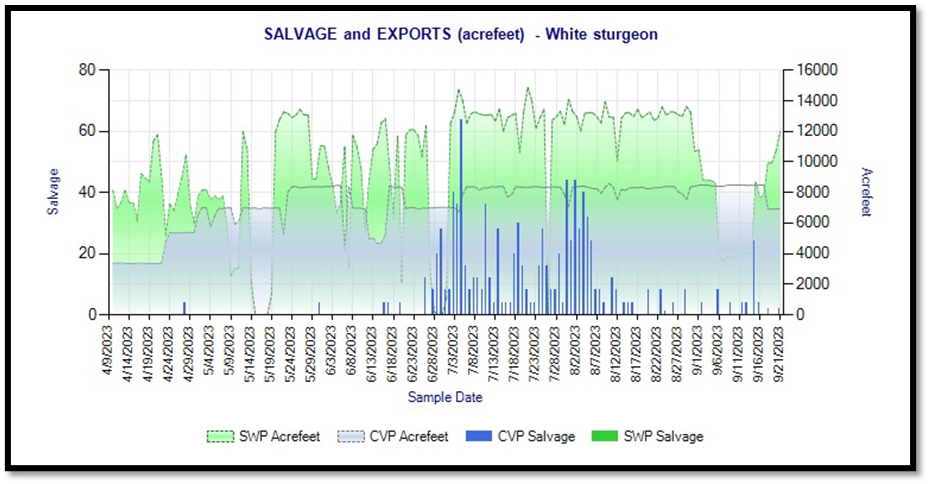

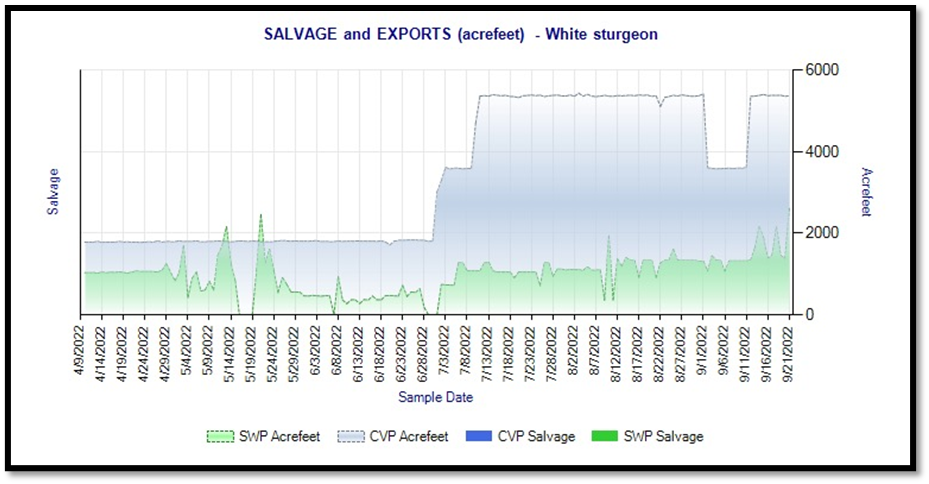

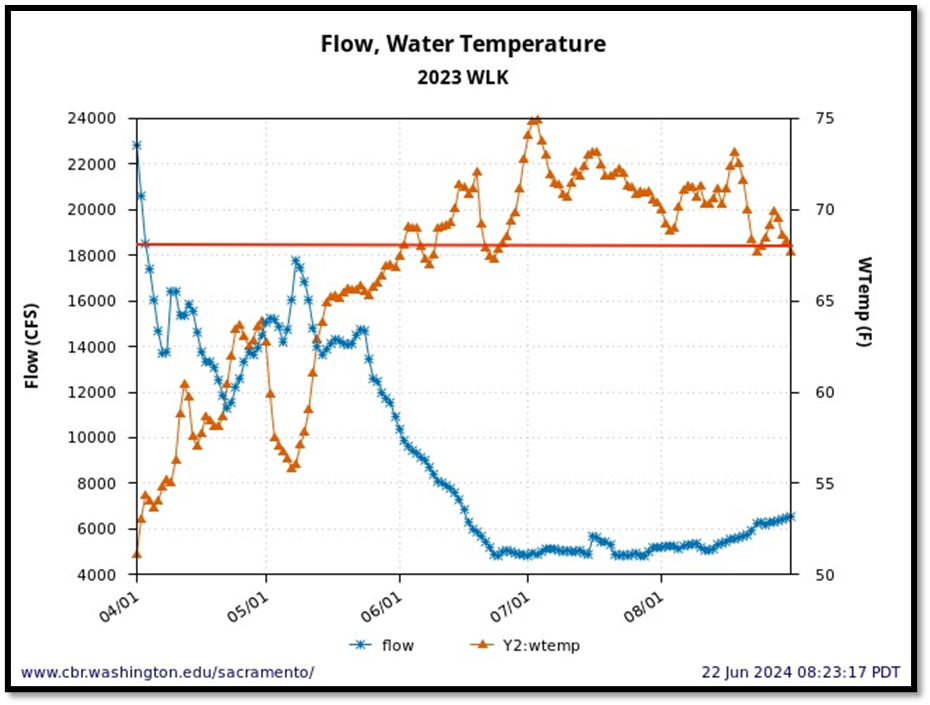

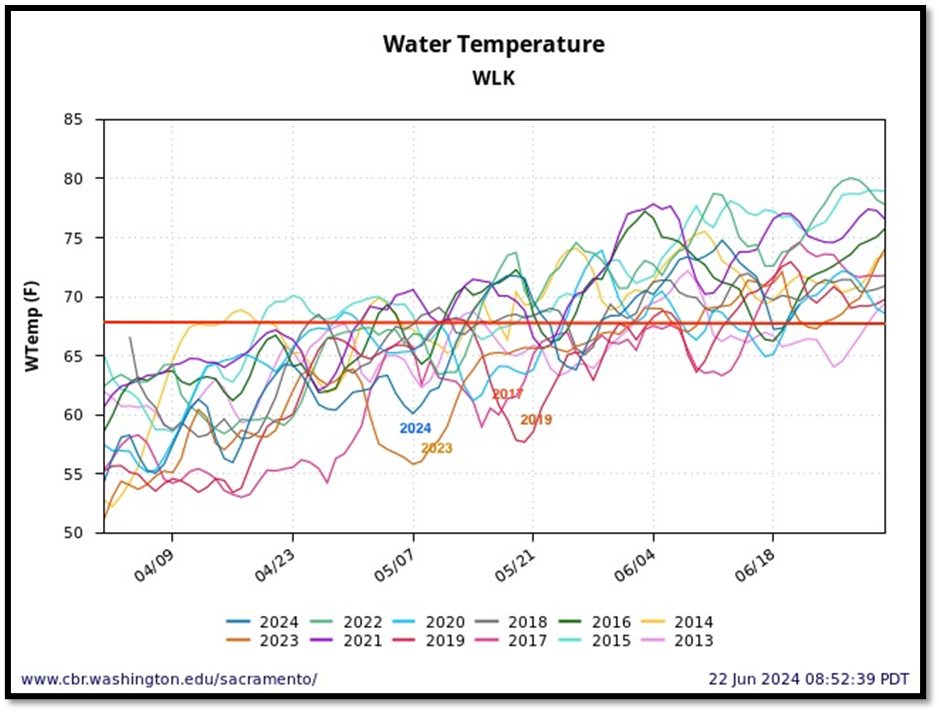

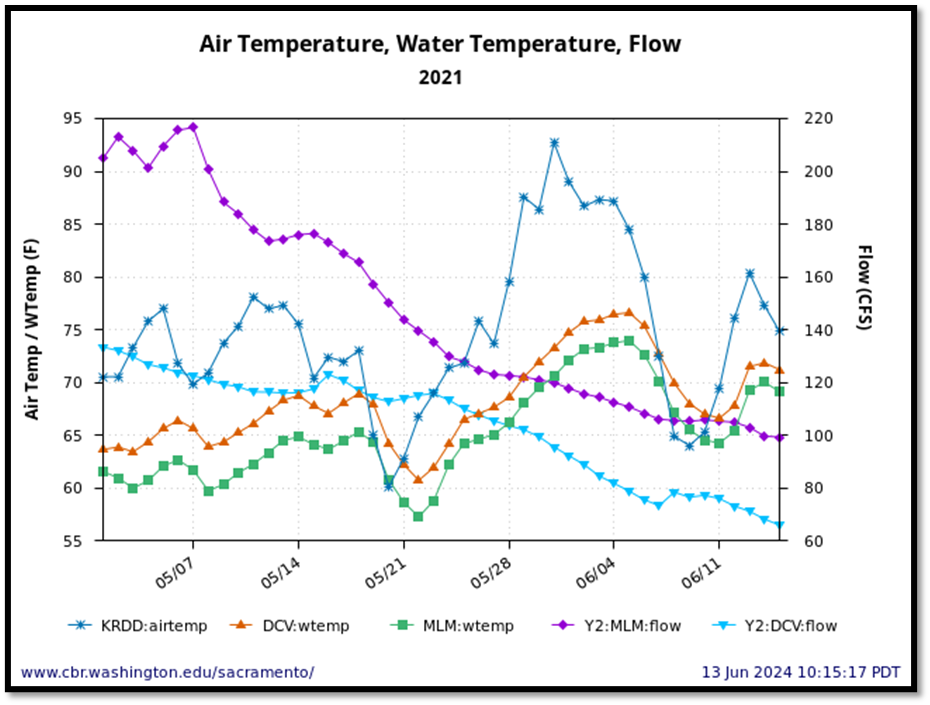

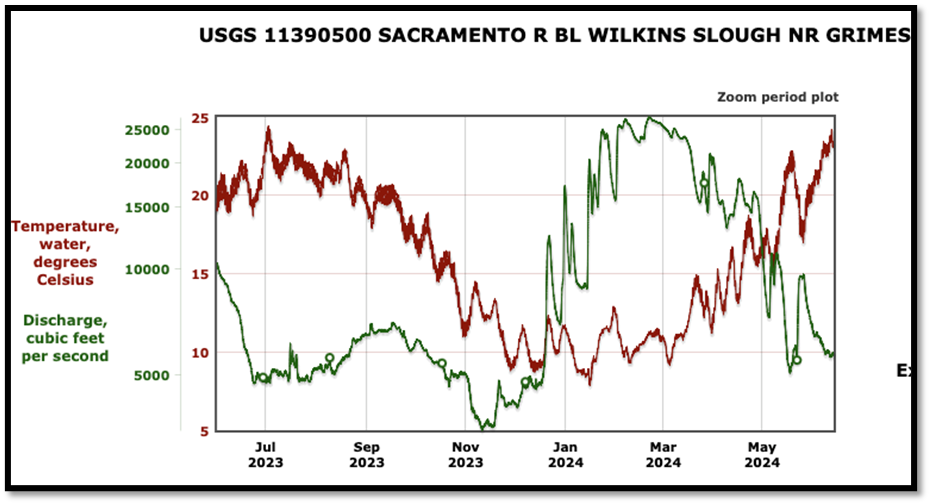

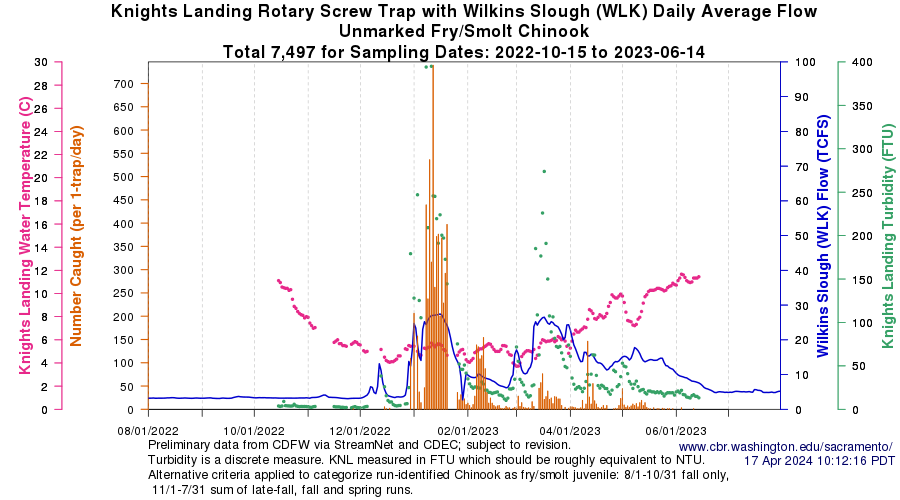

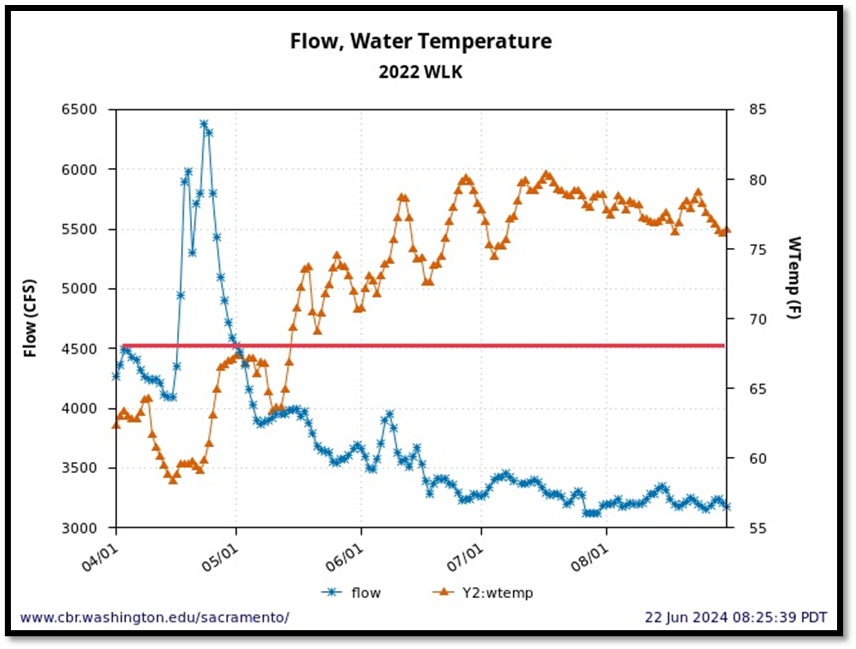

Figure 1. Drought year 2022 spring-summer streamflow and water temperatures at Wilkins Slough (RM 120) upstream of the Delta. Red line shows the target of 68ºF/20ºC needed to protect fish and keep the Delta cool.

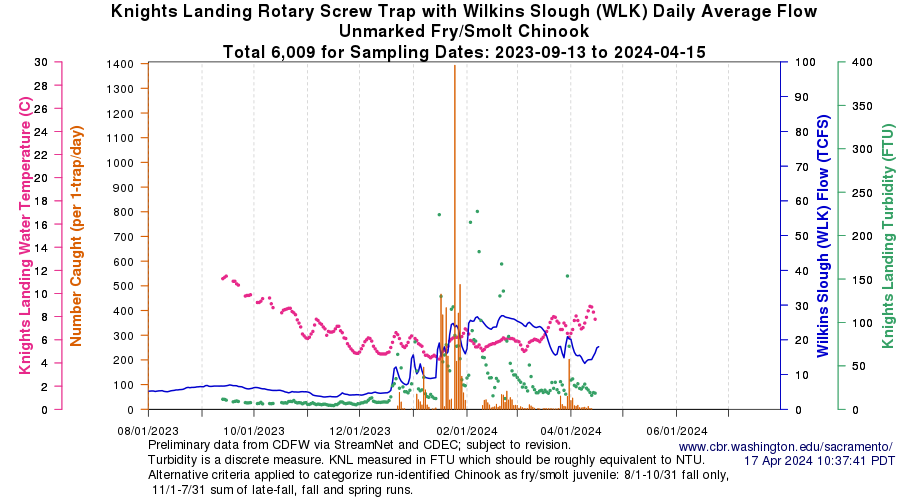

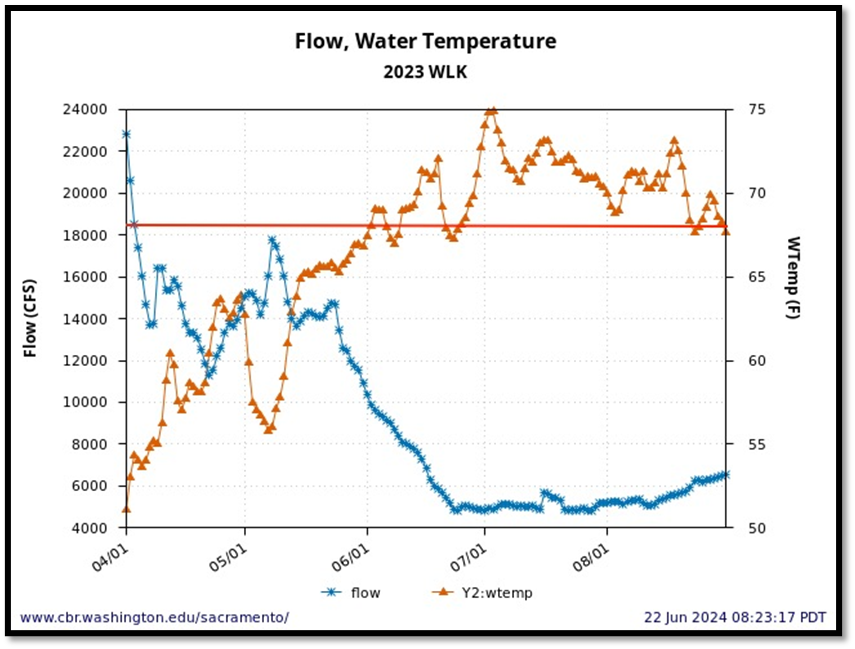

Figure 2. Wet year 2023 spring-summer streamflow and water temperatures at Wilkins Slough (RM 120) upstream of the Delta. Red line shows the target of 68ºF/20ºC needed to protect fish and keep the Delta cool.

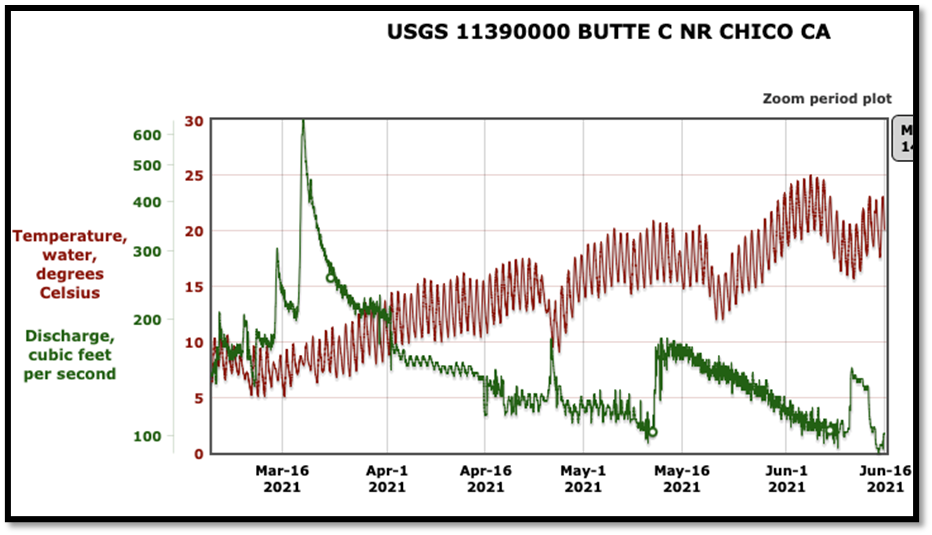

- The Sacramento River in the North Delta

Next is the Sacramento River channel in the north Delta’s Freeport to Emmaton reach, with Rio Vista in the center. This reach tends to emulate the input at Freeport, although it tends to warm when flow falls below 20,000 cfs (the inflow from Freeport, Cache Slough, and the San Joaquin River), as it too tends to warm as it slows down and sloshes back and forth with the tides in the summer sun. Delta diversions[1] can (and often do) take 12,000-13,000 cfs out of the 20,000 cfs Delta inflow (65% is the prescribed limit).

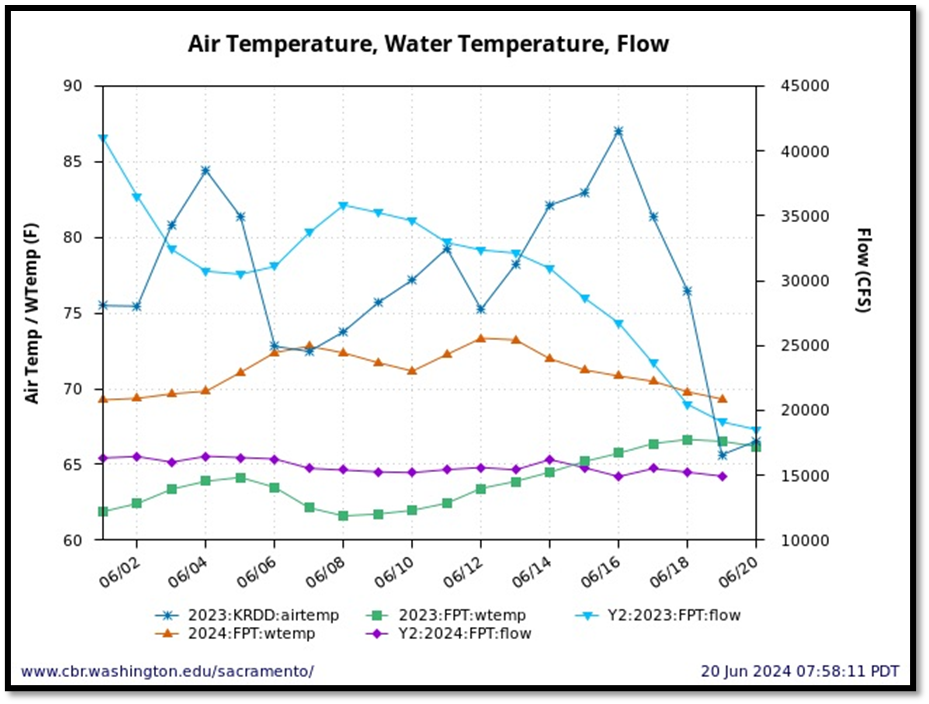

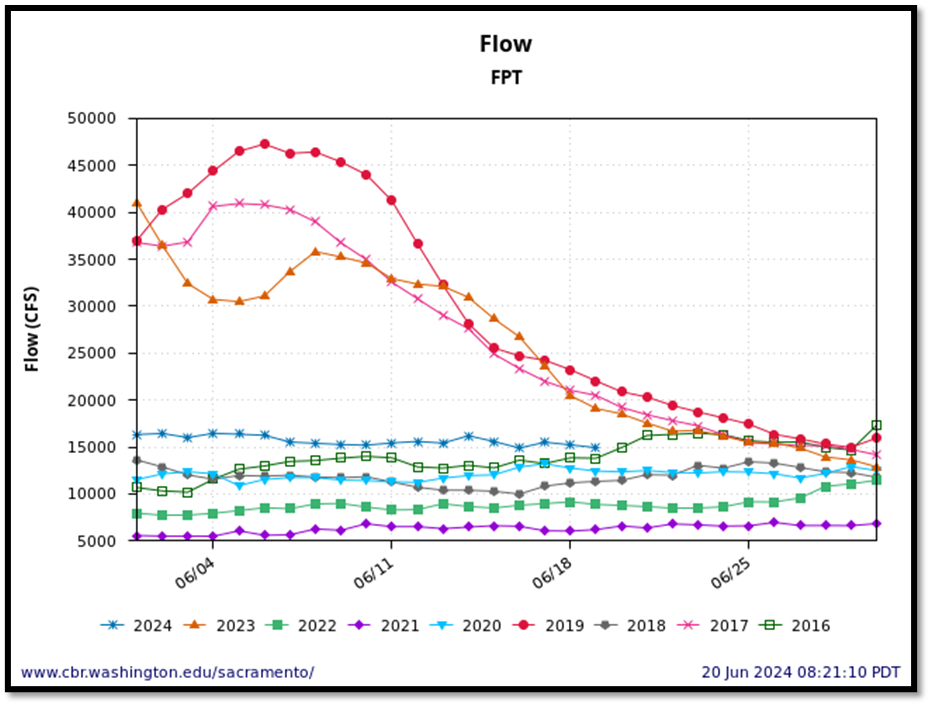

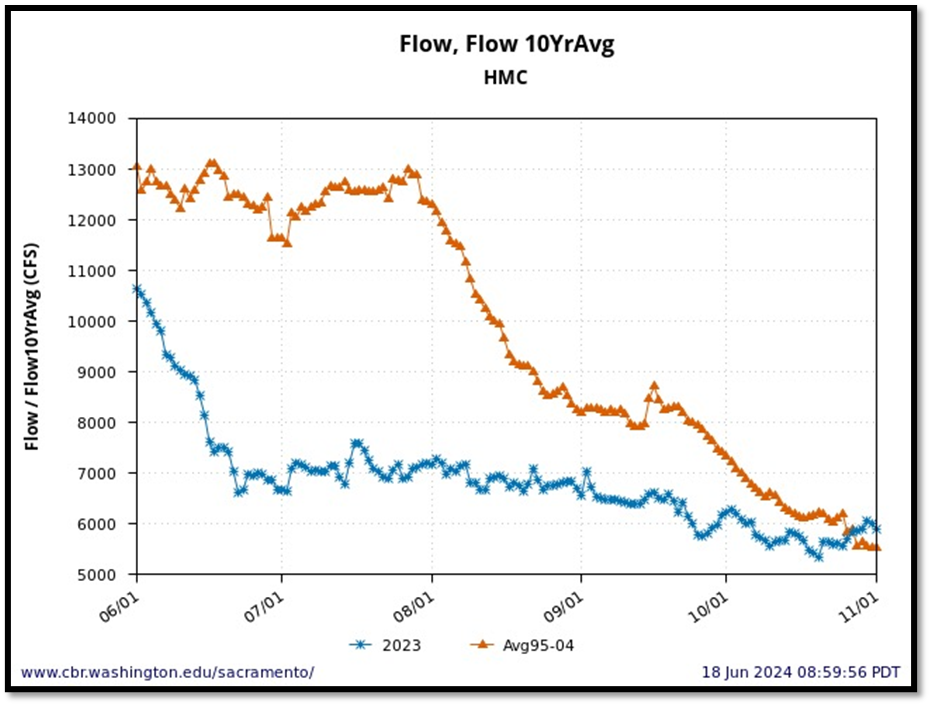

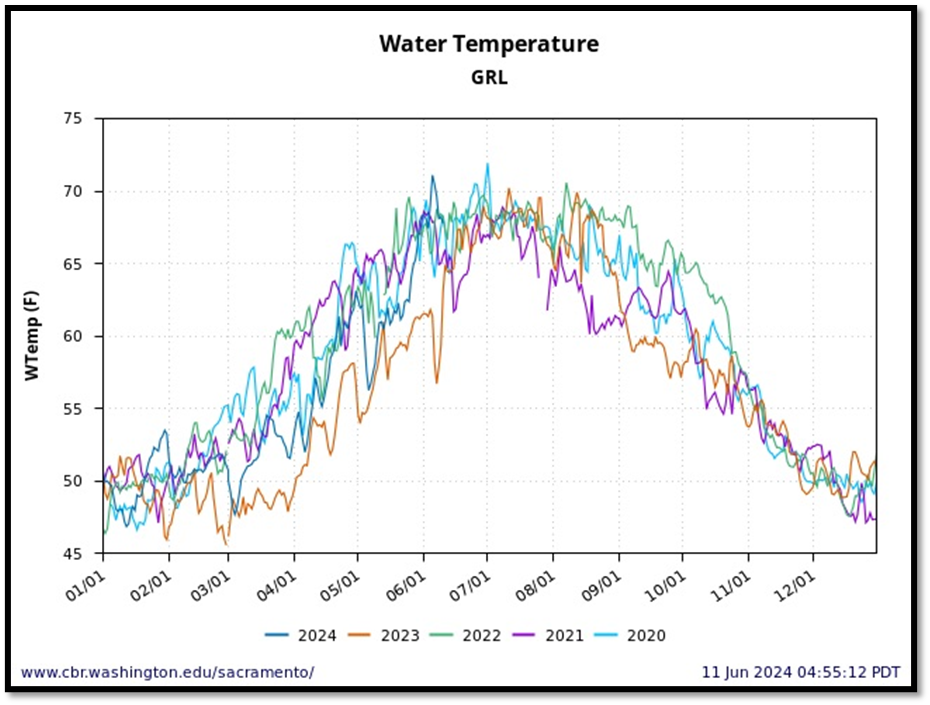

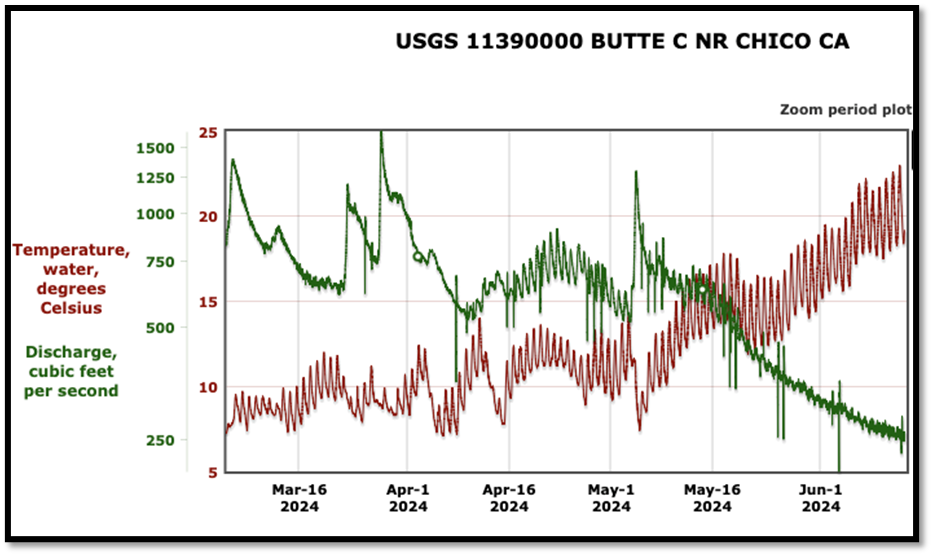

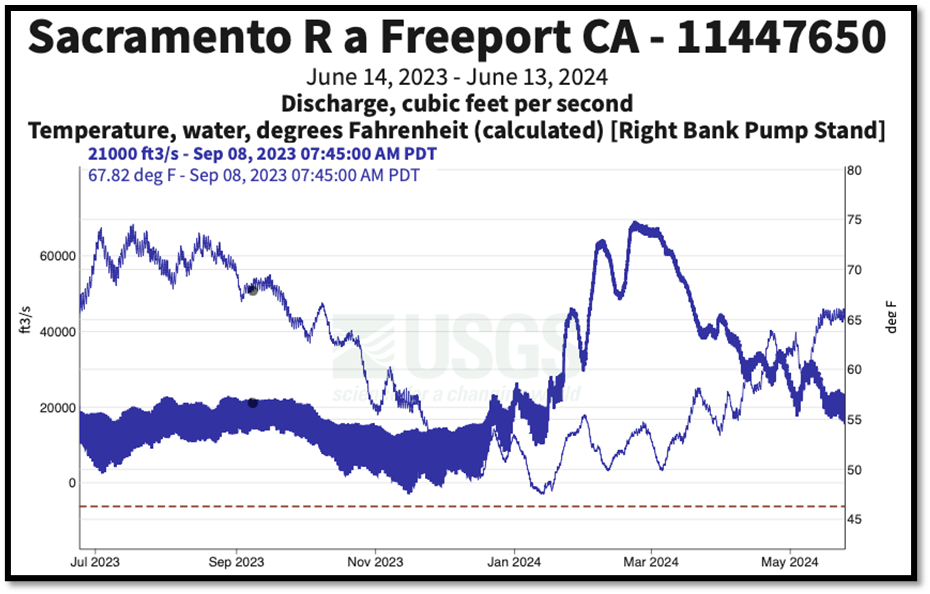

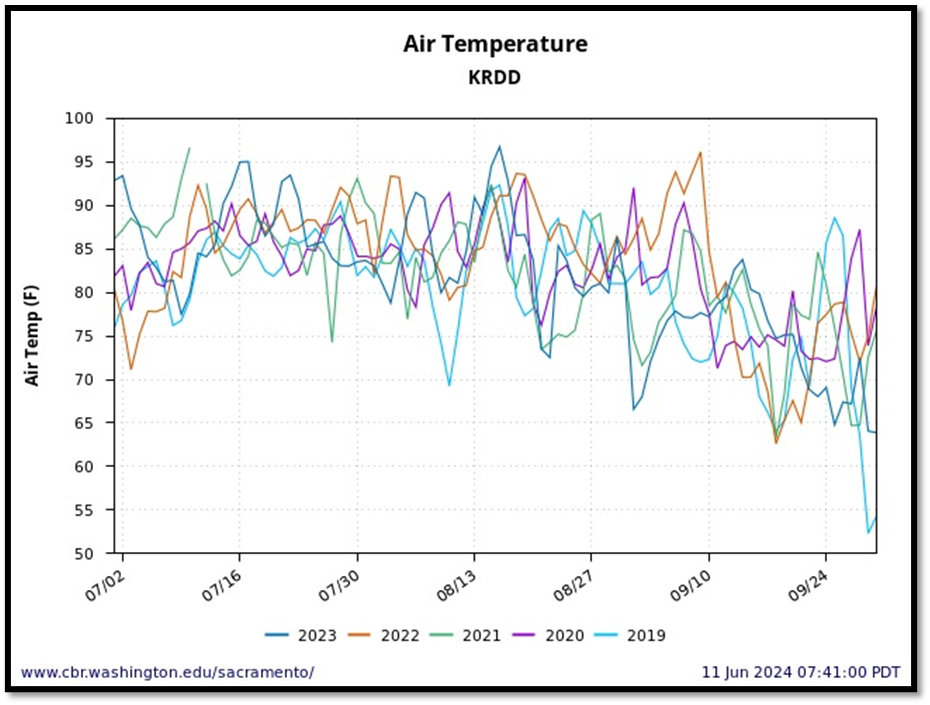

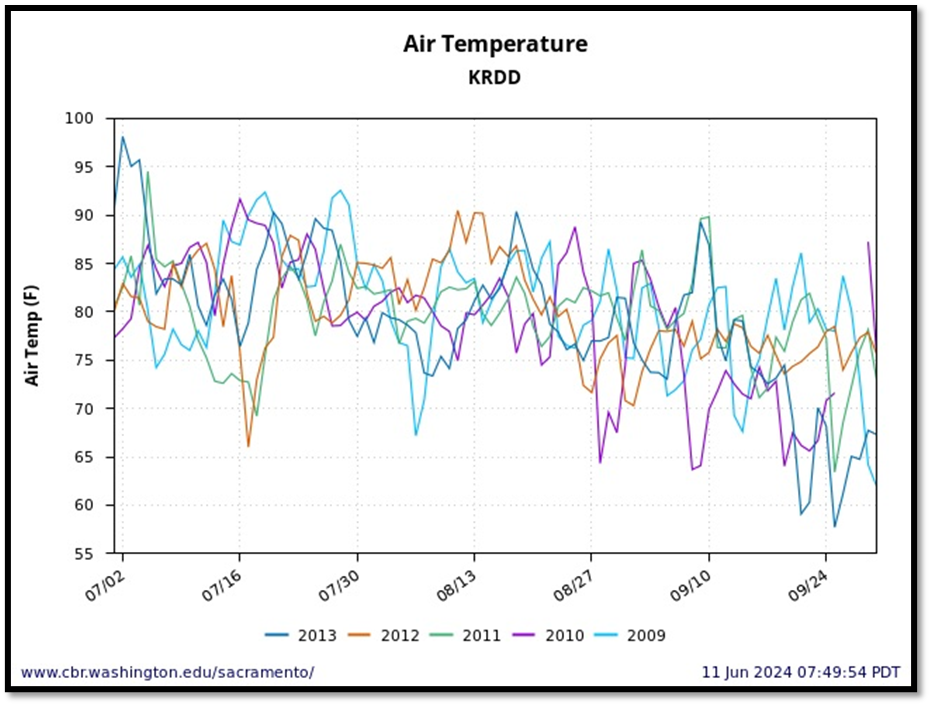

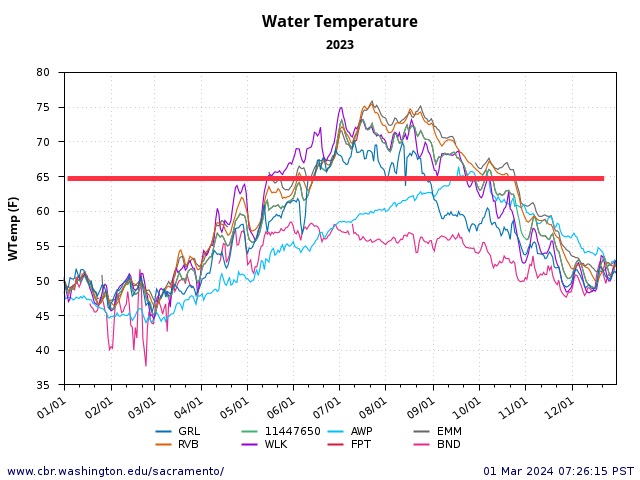

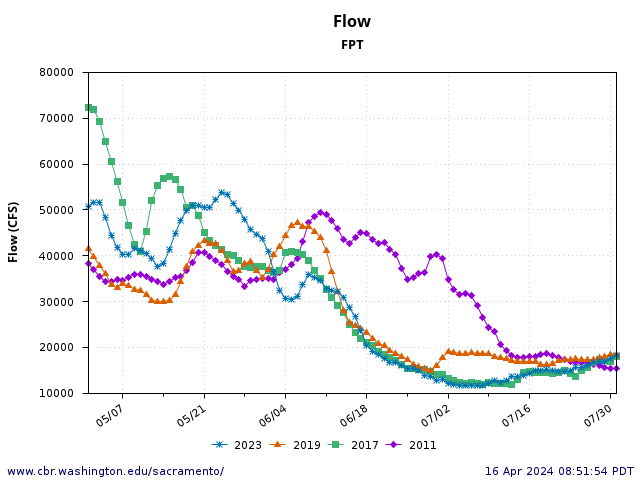

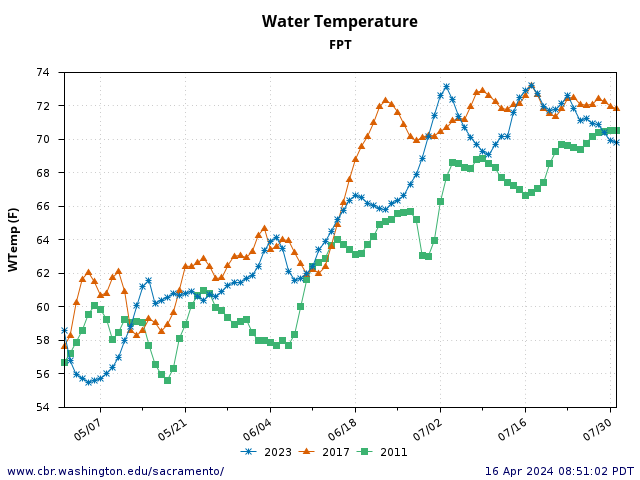

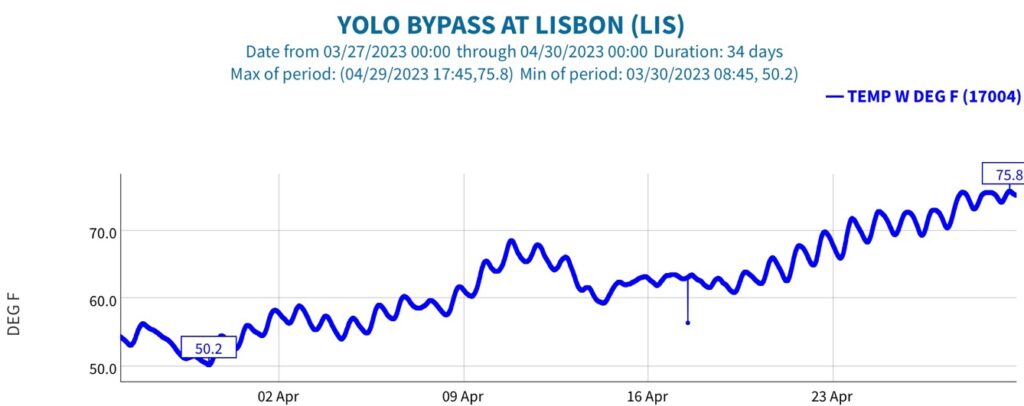

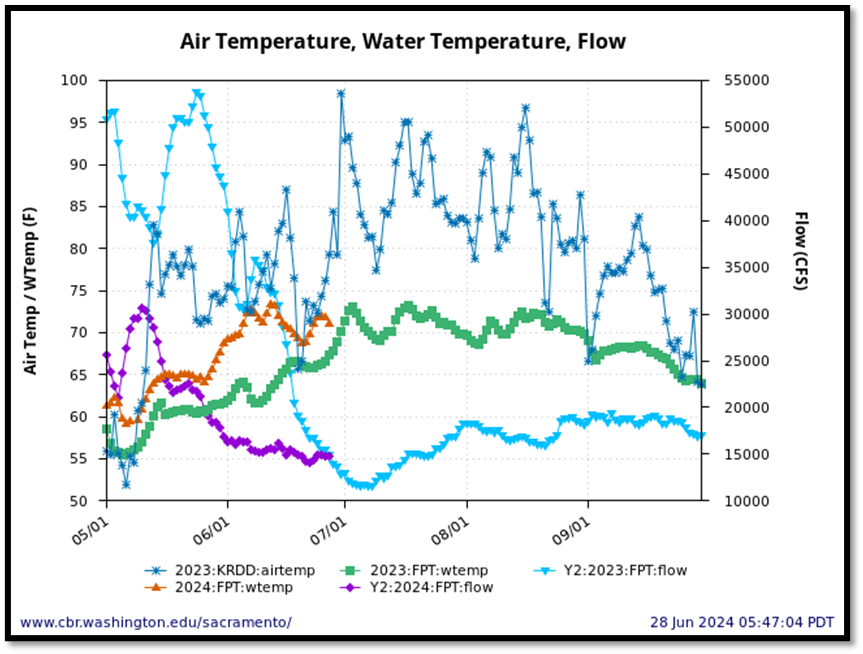

Input water temperatures at Freeport in June of 2023 and 2024, with streamflow of 15,000 cfs, were generally 70oF or higher (Figure 3). In 2023, inflows of 20,000-40,000 cfs brought water temperatures in the 62-66oF range with slightly higher water temperatures during heat waves. When streamflow at Freeport fell below 20,000 cfs in summer 2023, water temperatures reached 70oF or higher, especially during heat waves, when water temperatures spiked 2-4oF. Maintaining 20,000 cfs inflow at Freeport generally would bring water temperatures below 70oF.[2]

Figure 3. Wet year 2023 and above normal year 2024 spring-summer streamflow and water temperatures of the Sacramento River at Freeport (RM 90) at entrance to the Delta.

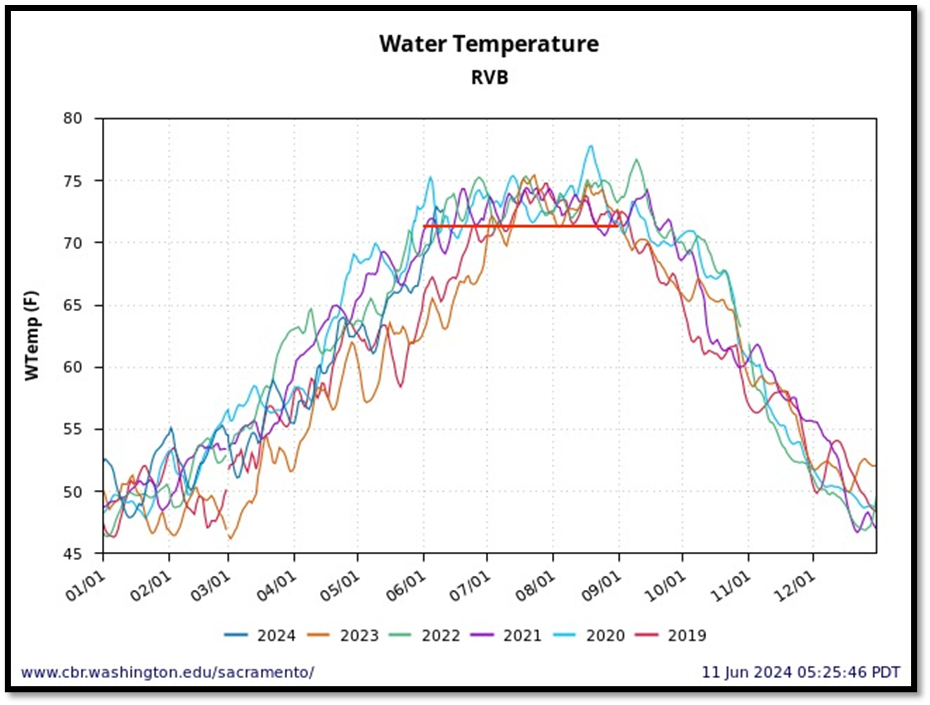

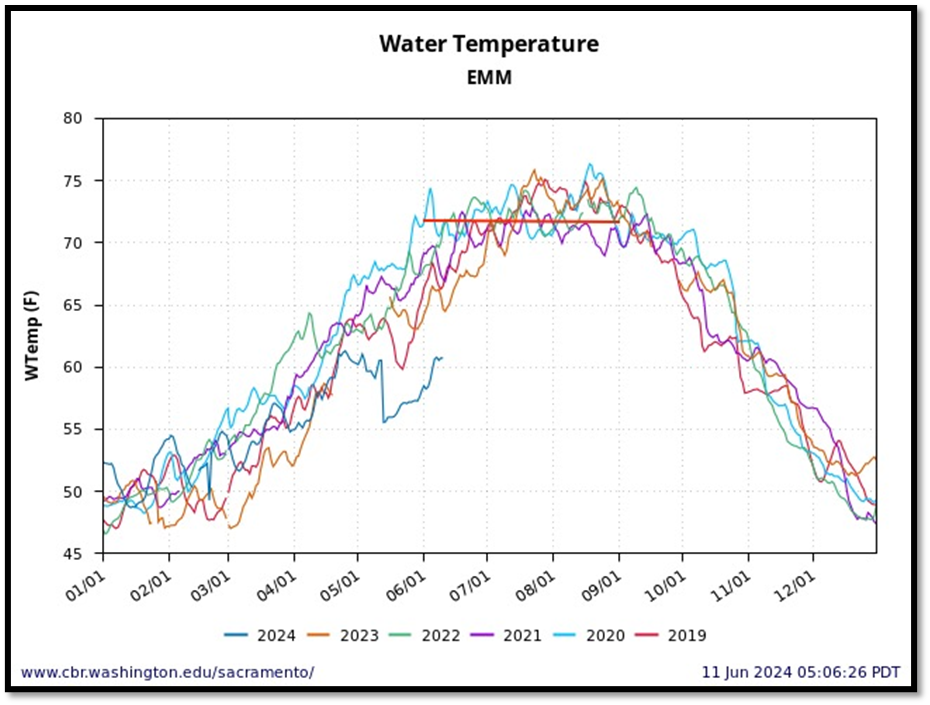

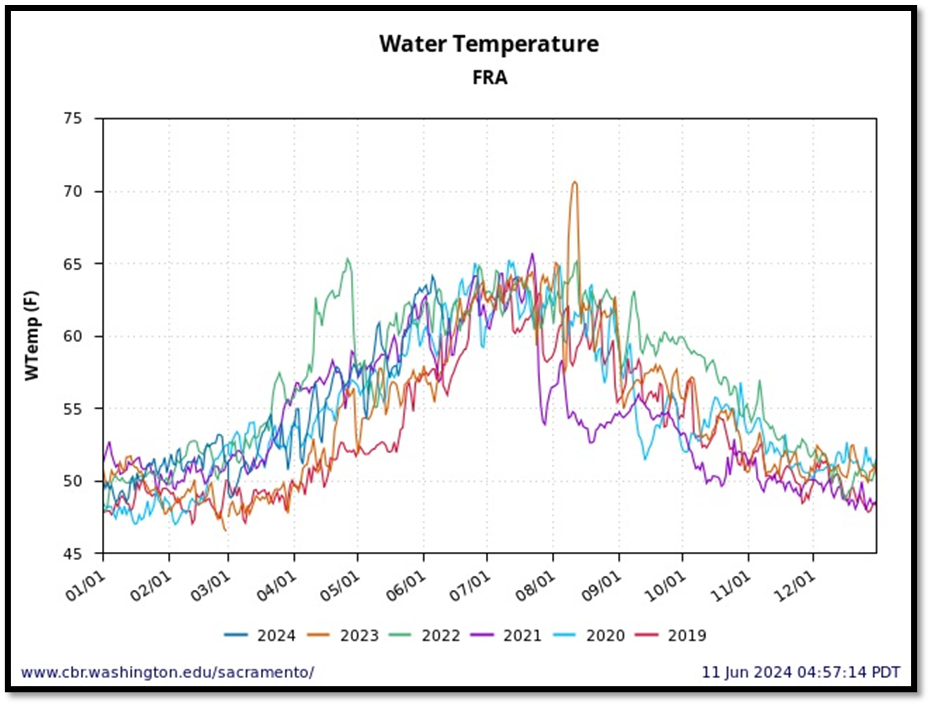

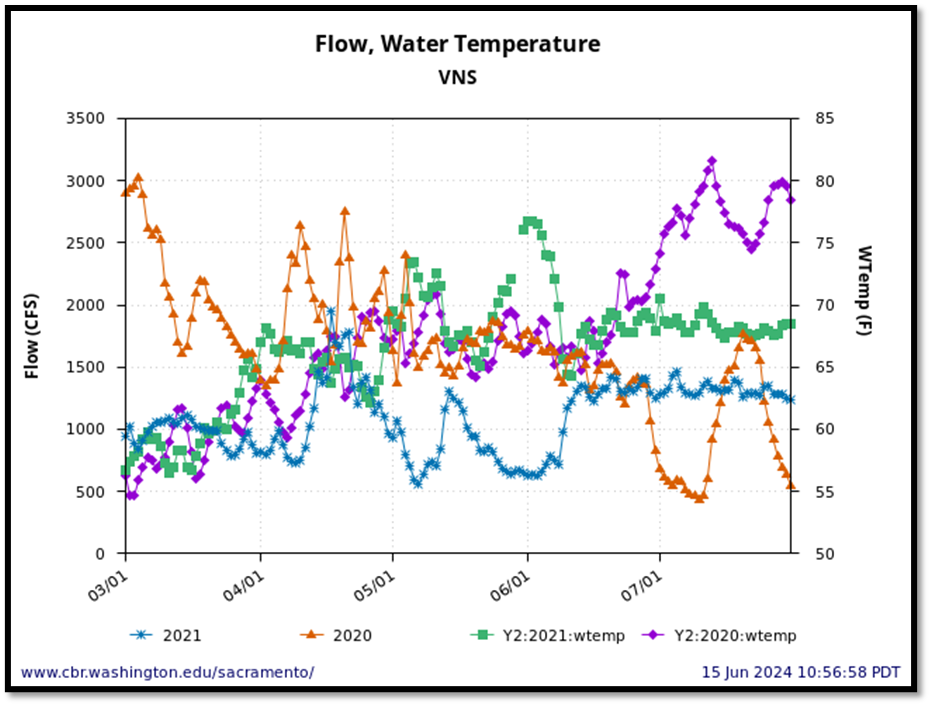

Downstream of Freeport in the central portion of the Sacramento River north-Delta channel at Rio Vista Bridge, water temperature patterns are similar to Freeport although slightly warmer and more erratic (Figures 4 and 5). Rio Vista is subject to inputs of warmer water from Cache Slough and the San Joaquin River and thus tends to be slightly warmer than Freeport. Net river flows at Rio Vista are also lower, as Delta water diversions can markedly reduce the Delta inflows by this location. Operation of the Delta Cross Channel also complicates the flow splits upstream of Rio Vista. Cooler Delta air compared to the Sacramento Valley is also a factor. However, the main factors appear to be water temperatures and inflows from upstream (Freeport). Keeping Freeport streamflows cooler should keep Rio Vista water cooler, especially during summer heat waves like the three in July 2023.

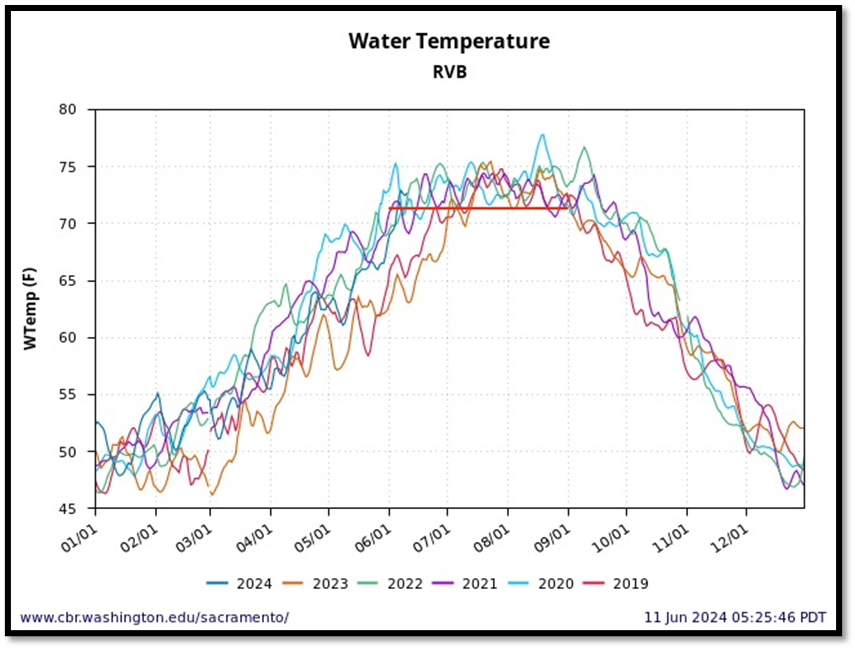

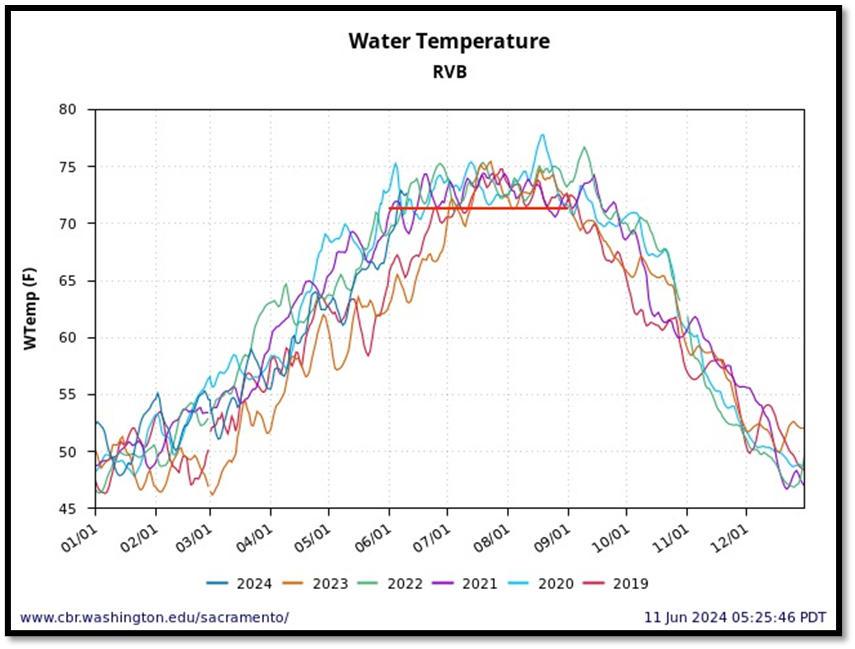

Figure 4. Water temperatures at the Rio Vista Bridge in the north Delta 2019-2024. Red line is recommended 72ºF limit.

Figure 5. Water temperature (daily average) at Rio Vista Bridge in north Delta from May-September 2023 – a wet year. Also shown are Rio Vista Bridge (Delta) and Red Bluff (Sacramento Valley) daily average air temperatures.

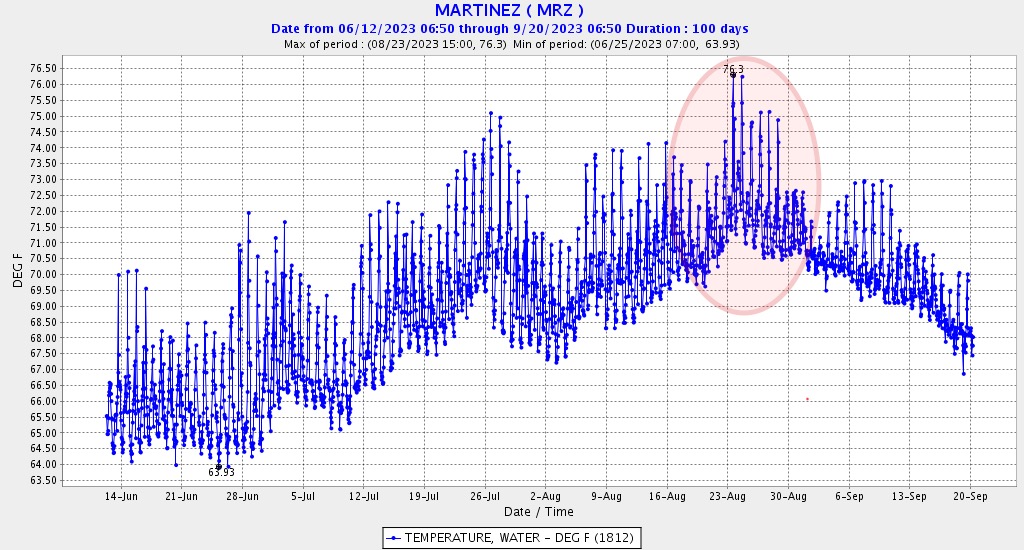

- The Bay

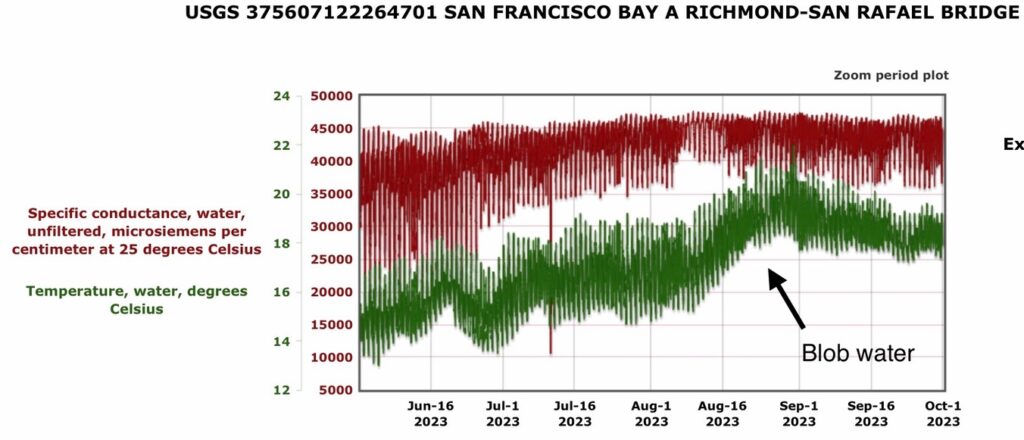

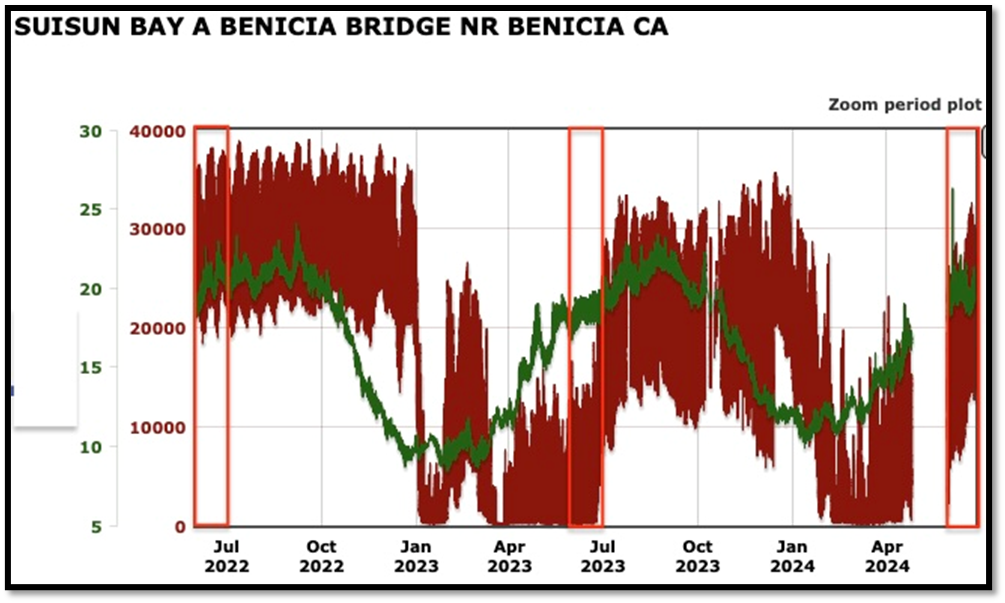

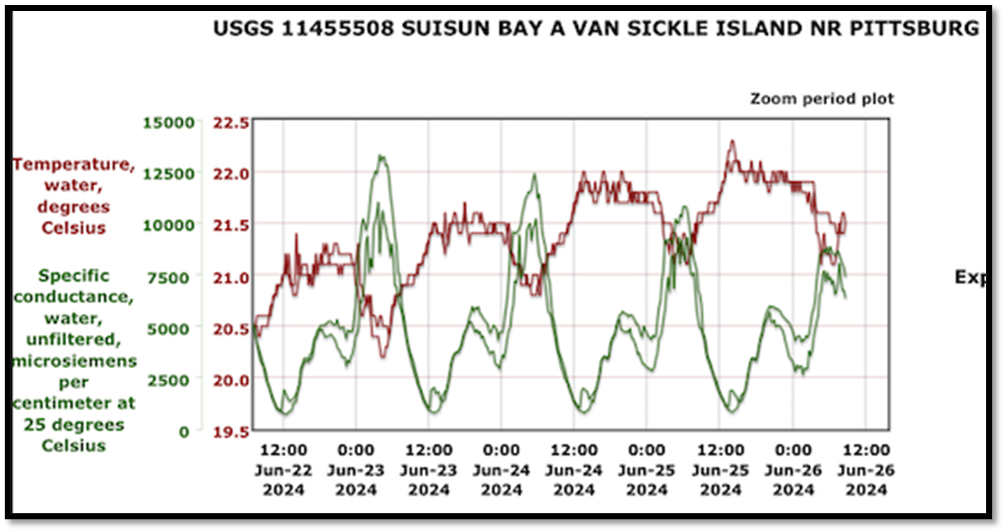

Summer Bay water temperatures are a function of inputs from the Delta and ocean, and of local air temperatures and tidal circulation. At the Benicia Bridge between the east Bay (Suisun Bay) and the north Bay (San Pablo Bay), the influence of freshwater inflows is not unlike that in the rivers and Delta. In wet years like 2023, high freshwater inflows in June kept salinity and water temperature lower (<20oC/68oF) (Figure 6). Warm water generally comes in from the Delta, especially during the twice monthly tidal-cycle draining of Delta water into the Bay (Figure 7). A one-foot stage drop from the 500,000-acre Delta into the Bay is 500,000 acre-ft of warm Delta water that over several days can have a measurable effect on the Bay. The late June 2024 full super moon is already heating the Bay with warm river and Delta water (Figure 7). A cooler Delta would make for a cooler Bay.

Figure 6. Hourly water temperatures and salinity (EC) at Benecia Bridge in west Suisun Bay June 2022-June 2024. Red boxes denote June periods in each year.

Figure 7. Hourly water temperature (degrees C) and salinity (EC) in east Suisun Bay in late June 2024 after full moon. Note warm fresher water from upstream (Delta) on ebb tides.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Poor water conditions in the Sacramento River, Delta, and Bay this summer will have negative effects on salmon, sturgeon, and other native fish populations. Unless there is action to mitigate these effects, the summer fish die-offs that occurred in summers of 2021-2023 in the Bay are likely to occur again this summer. The following actions can reduce these negative effects:

- Maintain the water quality standard of 68oF (daily-average) in the lower Sacramento River at the Wilkins Slough gage. This will require raising river flow from the planned 4000-5000 cfs level to 6000-8000 cfs level or higher (during heat waves).

- Maintain an average daily Delta freshwater inflow of 20,000 cfs at the Freeport gage.

- Increase the freshwater inflow above 20,000 cfs and/or reduce Delta water diversions as necessary during heat waves to maintain a daily-average 68oF at the Freeport gage and maximum hourly 72oF at the Rio Vista gage.

- Consider operational changes to the False River weir, Delta Cross Channel gates, and Montezuma Slough gates, which may also help reduce localized adverse effects.

[1] South Delta exports, smaller regional diversions, Delta agriculture, etc.

[2] Based on review and analyses of many years of data at Freeport and other locations.