The loss of juvenile and adult salmon in the Sacramento River floodplain has been a problem for many decades. The problem is largely the result of the construction of dams, agricultural drains, and flood control systems. The problem is acute, and although well documented and quite obvious, little has been done to resolve it. The fixes are not cheap and no one wants to get stuck paying for them. In addition, potential fixes have been hoarded as potential mitigations for large public works projects like the Bay Delta Conservation Plan and its associated Delta Tunnels.

The Problem

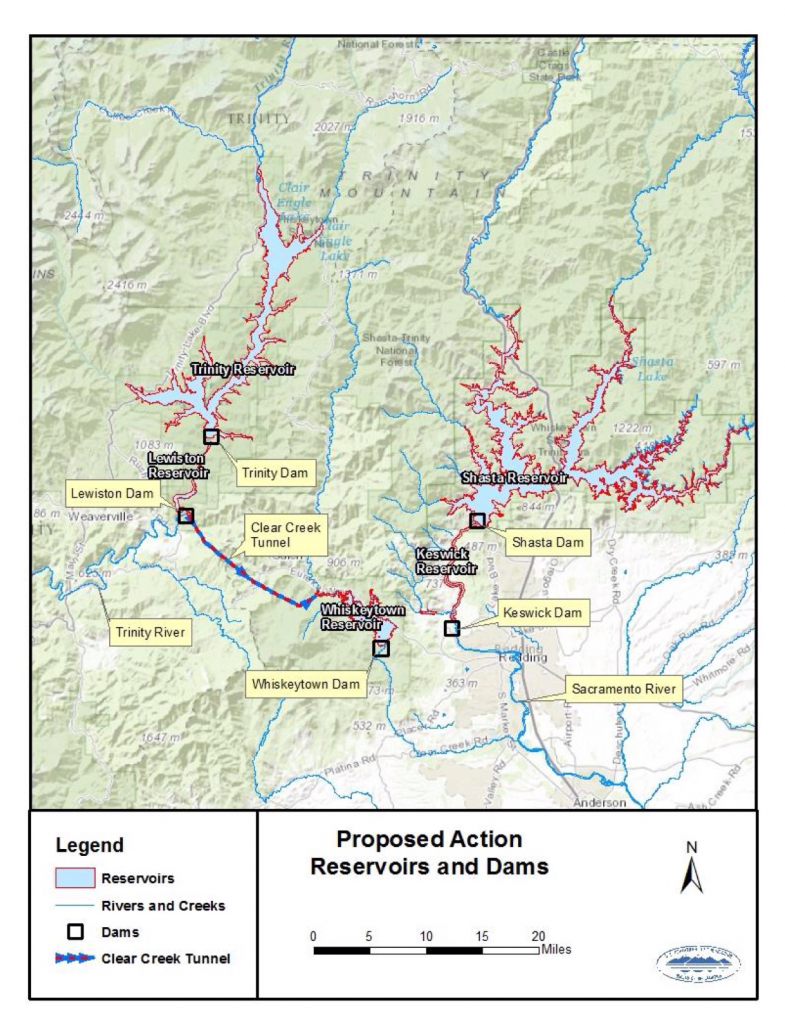

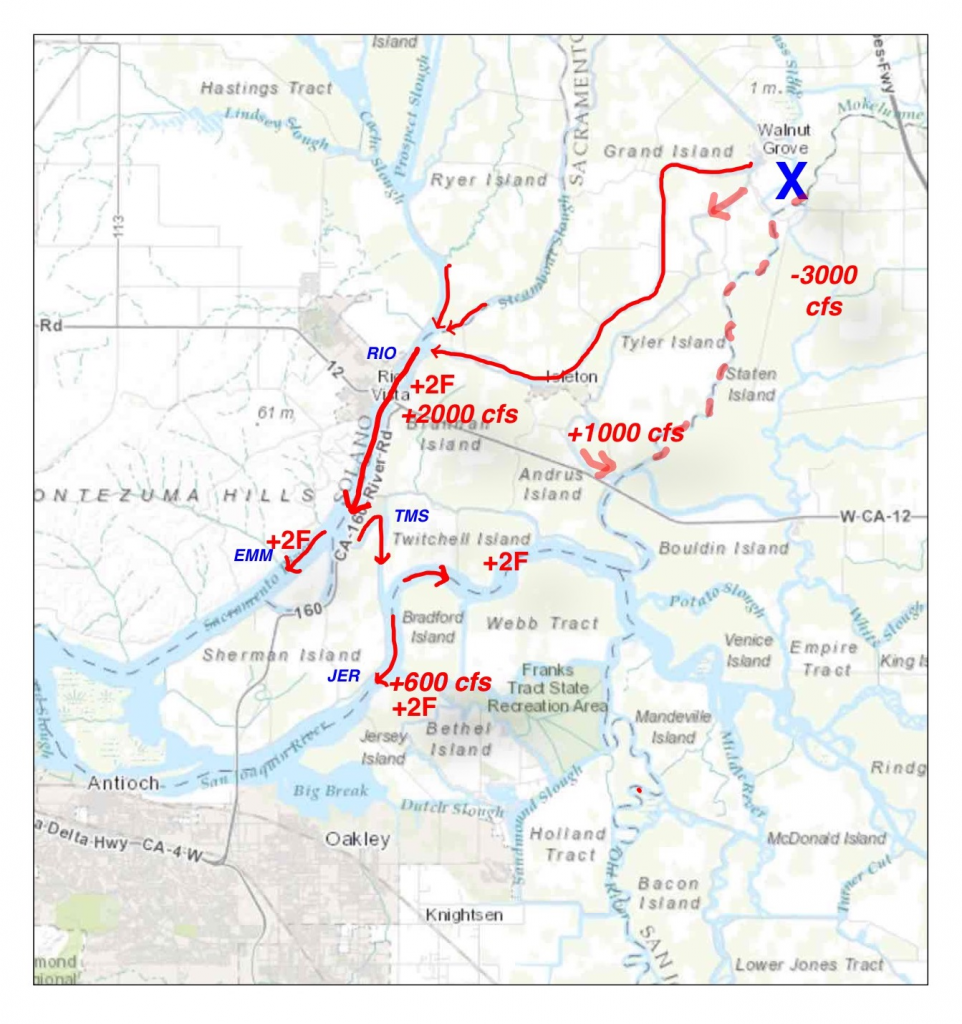

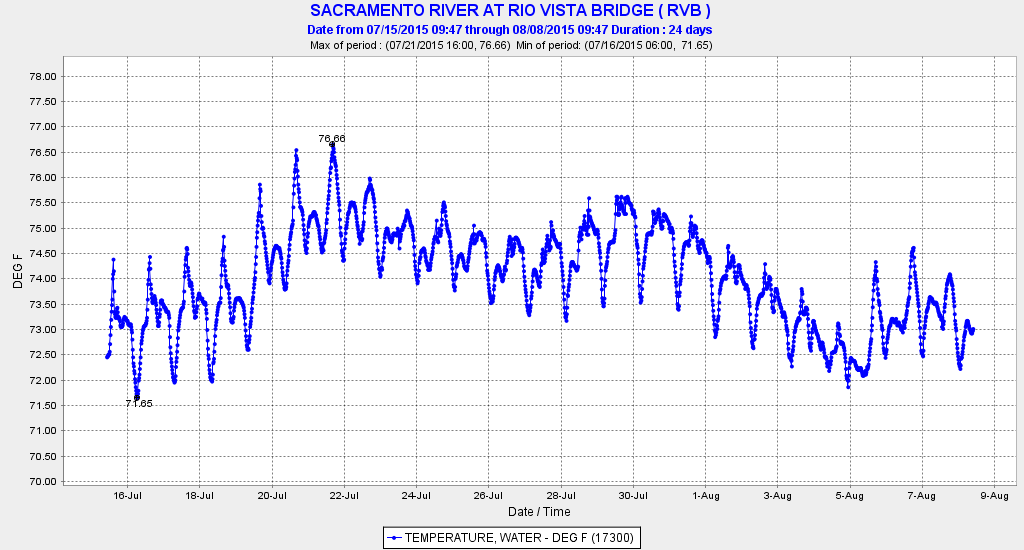

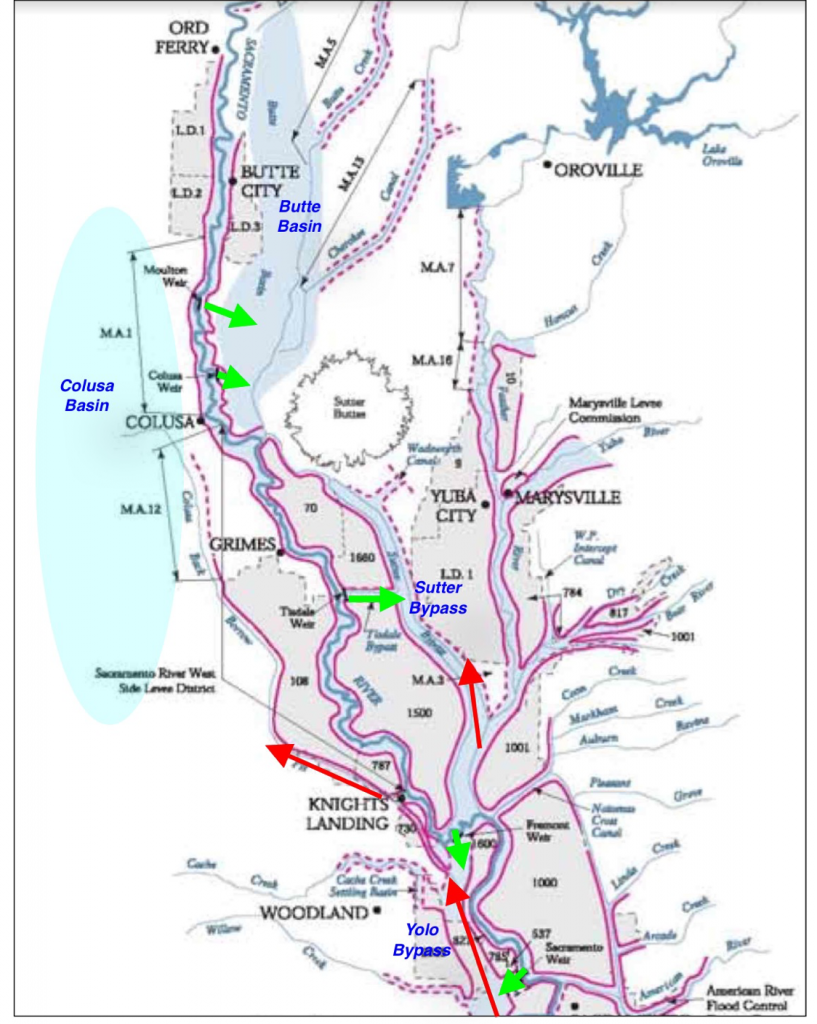

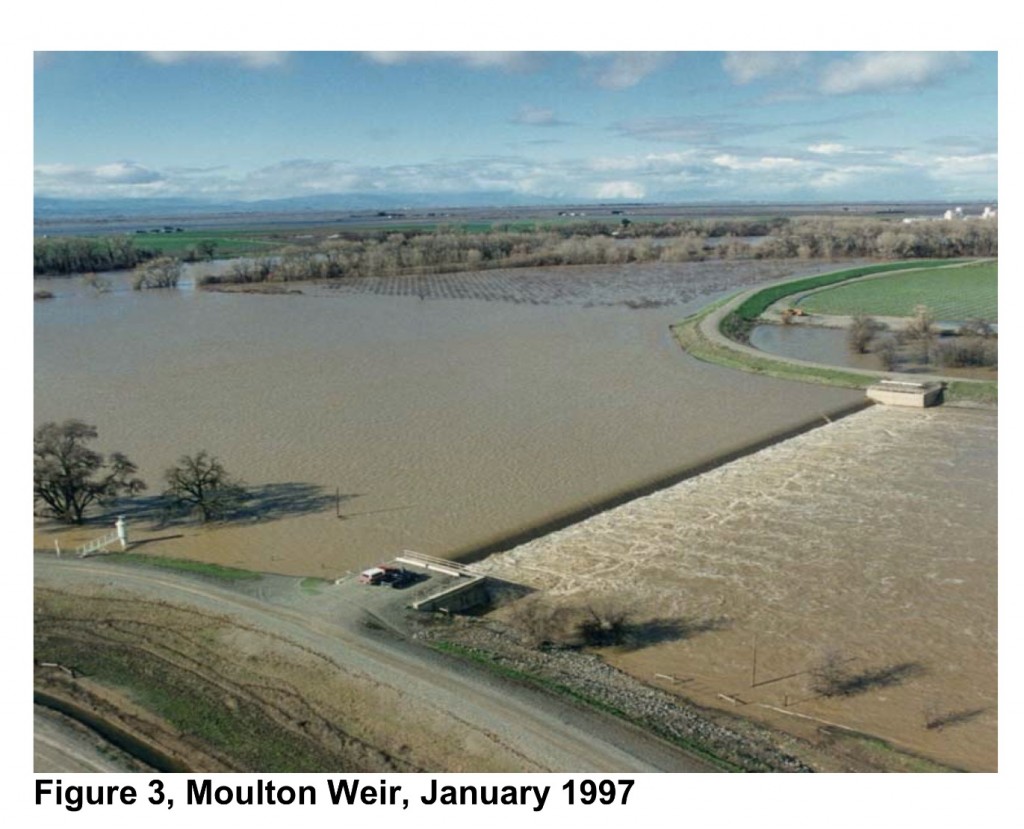

Figure 1 is a map of the Sacramento Valley with arrows showing some of the major locations of the problem. Much of the problem is the result of limitation or blockage of fish passage; another major factor is stranding. Adult salmon, sturgeon, and steelhead migrating up the Sacramento River become attracted to the high volumes of Sacramento water exiting the Sutter and Yolo Bypasses (adult fish movement is shown by red arrows in Figure 1), only to be blocked at the high weirs at the upstream end of the bypasses (Figures 2 and 3). Even modest bypass flows in drought years can cause attraction and subsequent mortality (Figure 4).

Young salmon emigrating downstream from upriver spawning grounds pass into the bypasses (green arrows in Figure 1) and adjacent basins in huge numbers. Many become stranded and lost when flows and water levels decline when weirs quit spilling (the river can drop ten feet overnight and quickly cease spilling into bypasses).

Landowners Seek Solution

In one of the areas, the Yolo Bypass, local landowners and stakeholders are seeking a solution. They are addressing three critical issues:

- Blockage of upstream migrating fish behind the Fremont Weir at the head of the Bypass.

- Blocked fish migrating to their deaths into the Colusa Basin from the Bypass via the Knights Landing Ridge Cut1. Adult migrants are also attracted directly to Colusa Basin Drain outlet even when Fremont Weir does not spill.

- Increasing survival of young salmon spilled into the Yolo Bypass by augmenting flows and improving habitats and habitat connectivity.

The first issue often occurs each time the weir spills at flood stage (generally one in three years, although it has not spilled significantly since 2006 because of drought). The bandaid treatment is shown in Figure 2. Stakeholders have advocated a short-term solution for passing fish via a “small notch” in the Fremont Weir to pass fish over the weir into the river; however, long-term agency plans call for a more contentious “large notch” in the weir.

The second issue requires the opposite solution, placing a fish-blocking weir at the outlet of the Knights Landing Ridge Cut to stop adult salmon, sturgeon, and steelhead from migrating upstream into the Colusa Basin. Landowners are working with the California Department of Water Resources and Reclamation toward building such a weir. For now the bandaid is a fish trap and fish rescues such as that shown in Figure 2.

The third issue can be resolved by engineering the bypass floodplain to provide better habitat and connectivity for the salmon including high and longer-sustained flows from the Fremont Weir (via a “notch”). Local landowners have developed an array of actions to provide habitat and connectivity.

In my experience, placing leadership and responsibility for developing and implementing actions in the hands of local stakeholders has worked best to help save fish. “Locals” can be surprisingly adept at coming up with viable solutions to fisheries problems.

Figure 1. Map of Sacramento Valley showing levees and flood control system weirs and bypasses. Gray area agricultural basins are generally below the elevation of the river and bypasses. The flood control system was initially designed to convey flood water and historic foothill mining debris through the Valley. Adult salmon (as well as sturgeon and steelhead) are attracted to the high flows entering, passing through, and exiting the Sutter and Yolo Bypasses (such adult migration is shown with red arrows). Many cannot successfully complete their passage either becoming lost or blocked at the upstream end by weirs (located at the blunt end of the green arrows). Many young salmon become stranded in the basins and bypasses after entering in spill over weirs during floods. (Map source: http://baydeltaconservationplan.com/Libraries/Dynamic_Document_Library/Fact_Sheet_-_Sac_River_System_Weirs_and_Relief_Structures.sflb.ashx )

Figure 2. Sturgeon being rescued below a Sacramento River bypass weir

Figure 4. High storm flows in late December 2014 into the Yolo Bypass from the Knights Landing Ridge Cut attracted many salmon to the northern end of the Bypass. When storm flows receded after several days, hundreds of adult salmon became stranded in winter-fallow fields that had been flooded. Many more salmon likely passed successfully into the Colusa Basin drain system only to find no route to spawning grounds in the upper Valley.