Sacrificed and Unprotected

Where are the newspaper articles about the American River “trout?”1 Water supplies and fish are suffering all across the Central Valley, but there is no mention of American River salmon and steelhead being sacrificed so that southern California reservoirs can be filled.

The Santa Clarita Valley Signal reported on August 31, 2016:

“Castaic Lake’s water levels increased due to a rainfall and snowpack in Northern California. Castaic Lake is part of the California State Water Project and is maintained by the California Department of Water Resources as one of the state’s 34 storage facilities. Water collected by the agency is moved around the state to provide drinking and agricultural water to two-thirds of California’s inhabitants. On average, Castaic Lake holds 264,908 acre-feet of water during this time each year. It is currently holding 241,689 acre-feet of water, which is 120,467 acre-feet more than the lake was holding this day in 2015.” 2

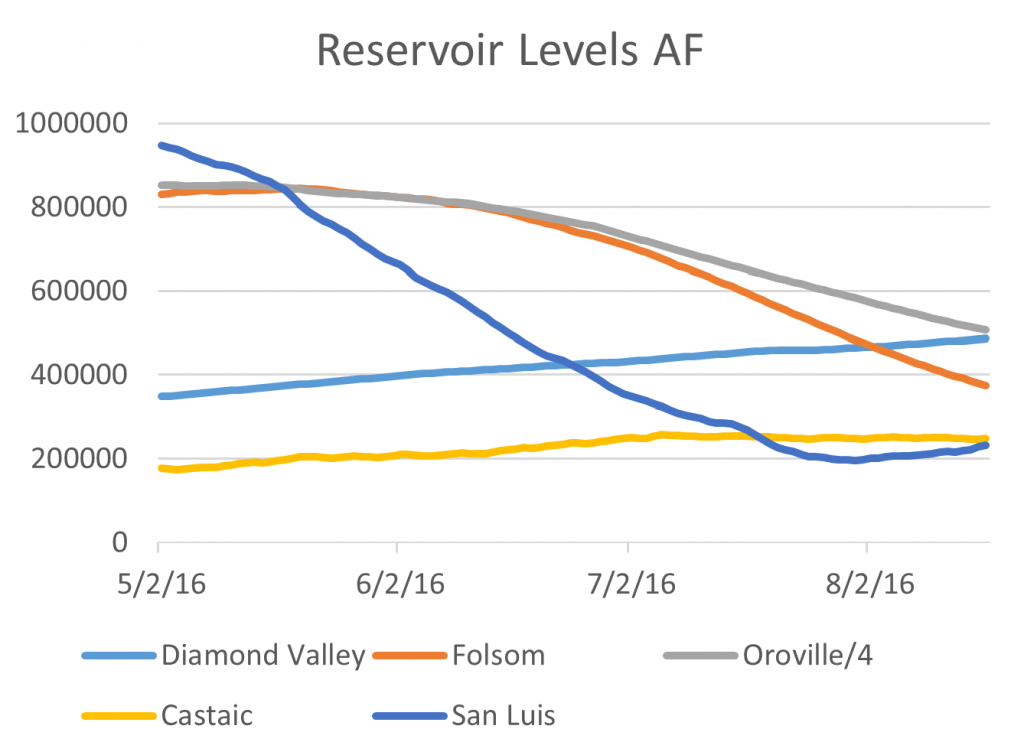

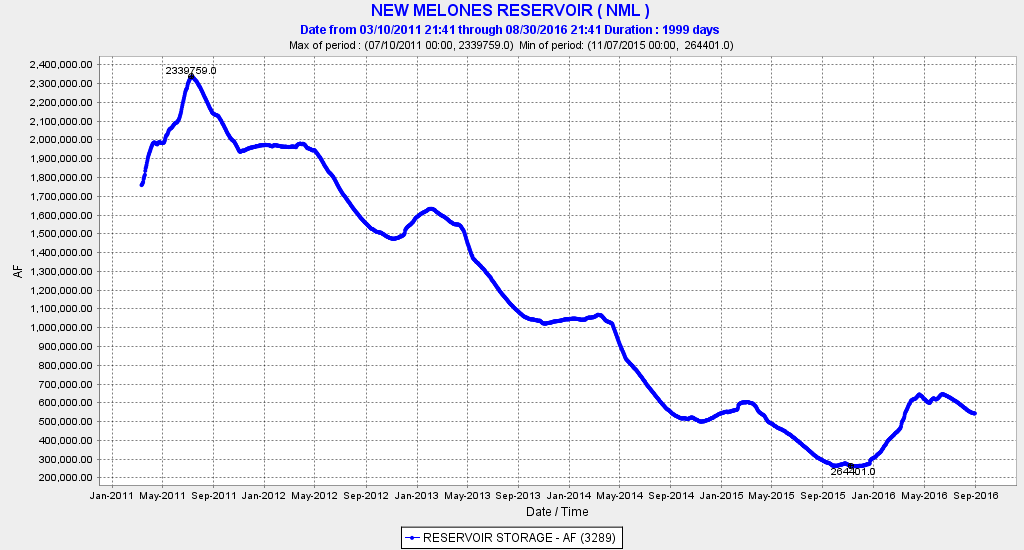

Yes, Southern California reservoirs are being filled at the expense of northern California reservoirs (Figure 1). Folsom Reservoir in particular was drained of over half its water over the summer, which has put this year’s steelhead and salmon spawns at great risk, not to mention future water supply and hydroelectric production needed by the Sacramento region.

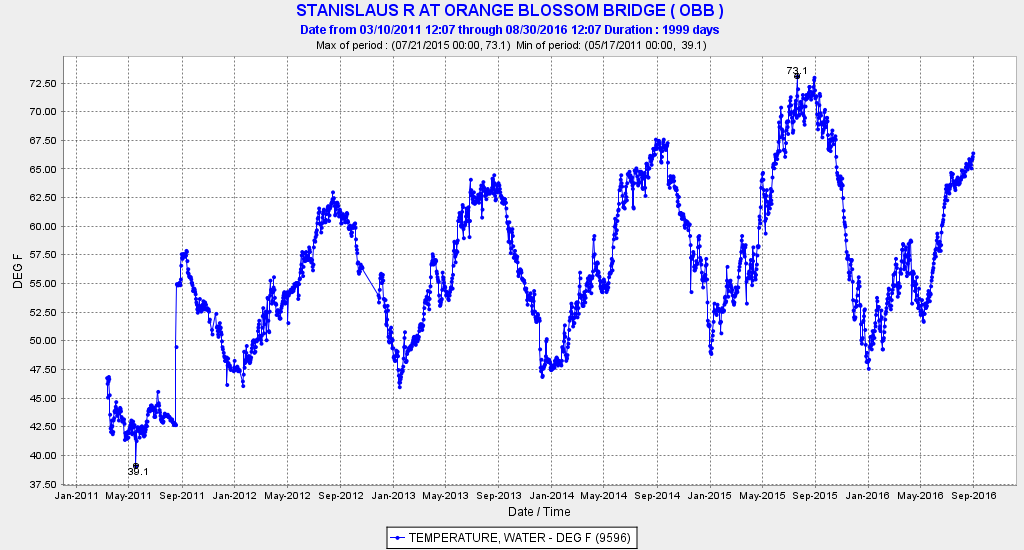

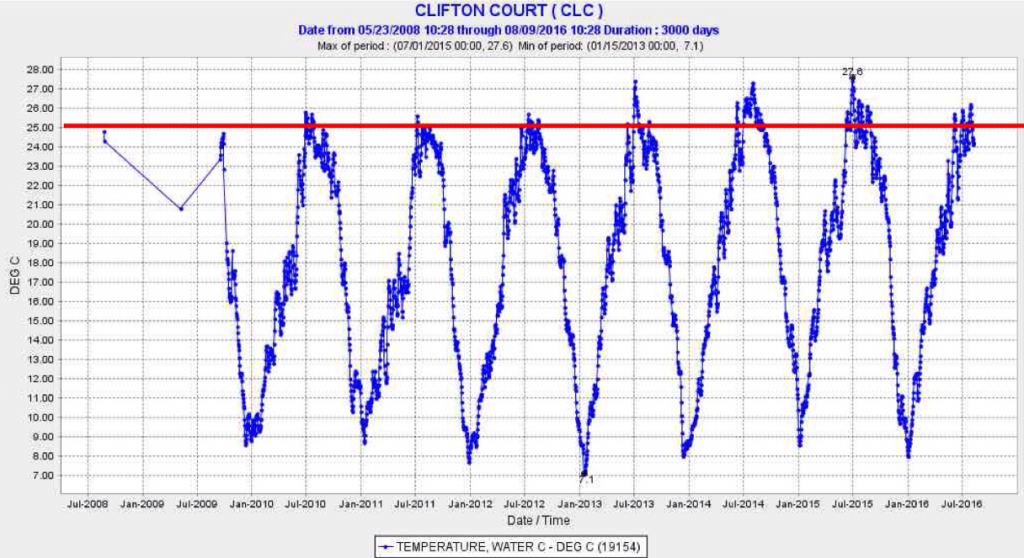

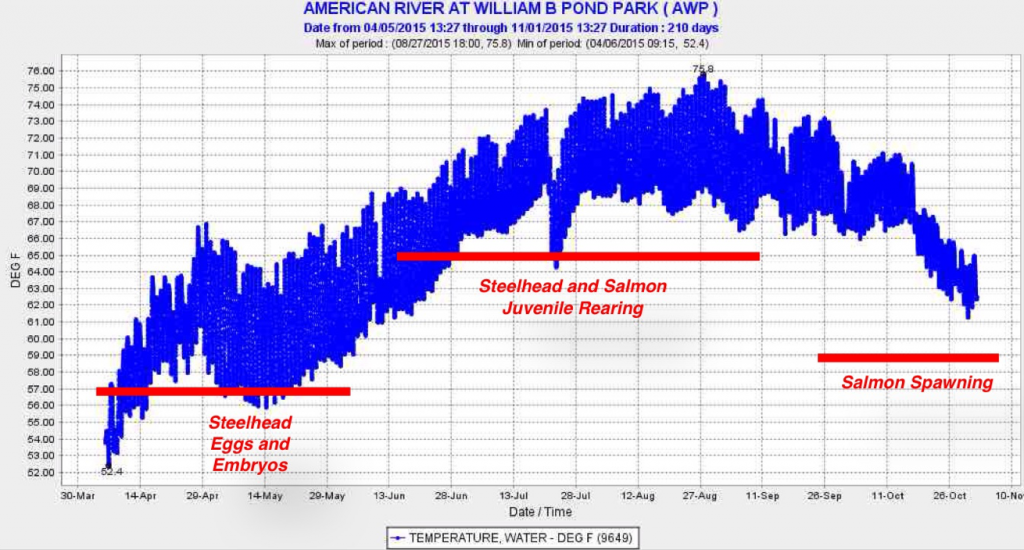

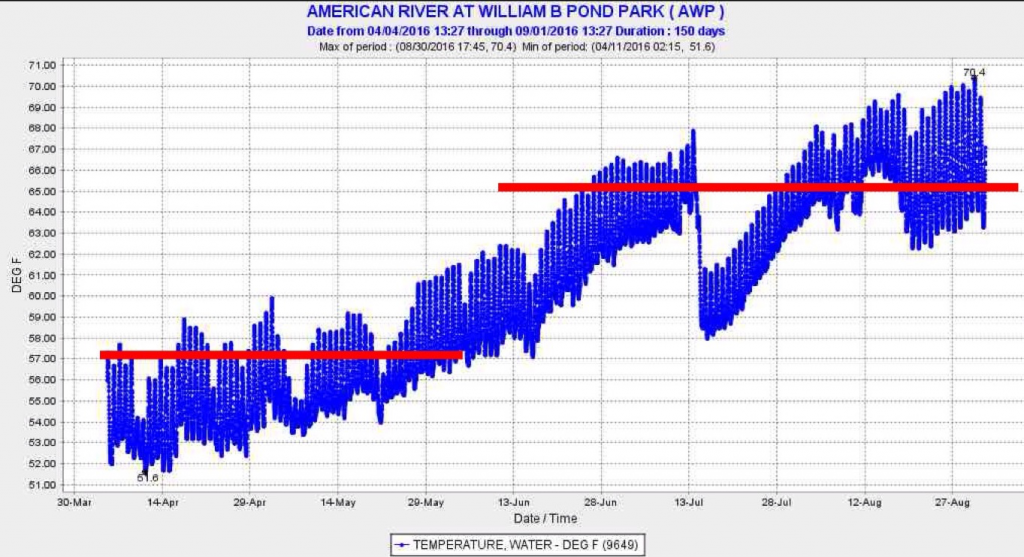

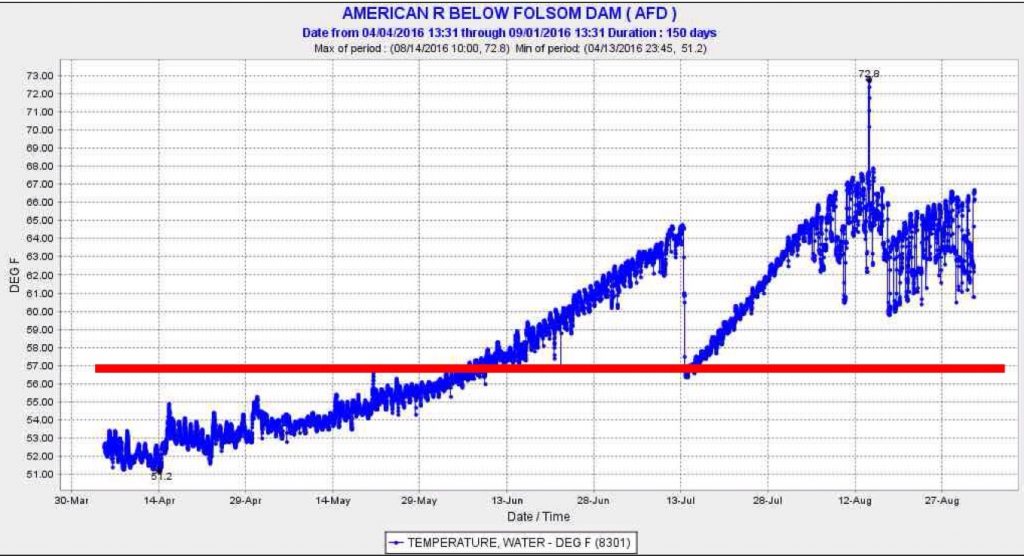

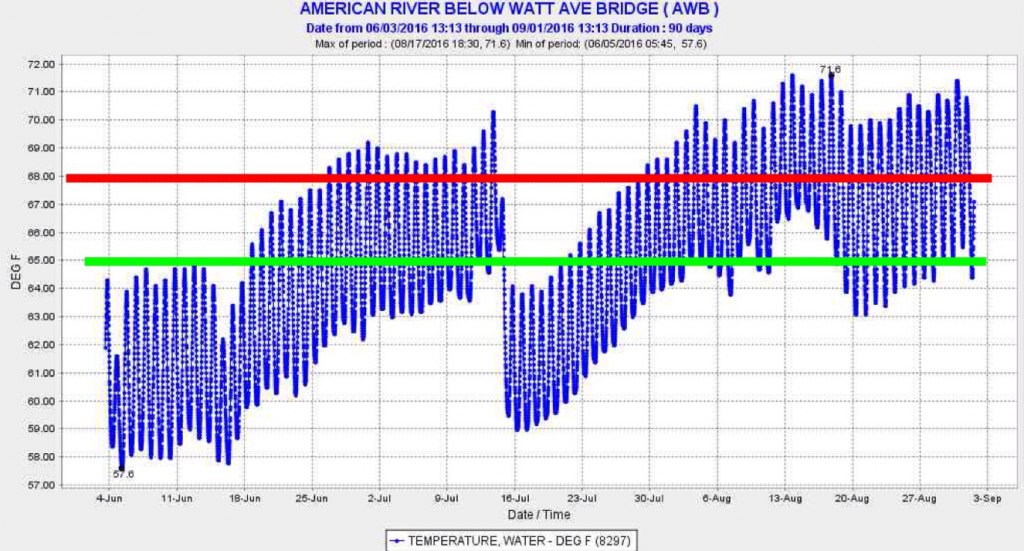

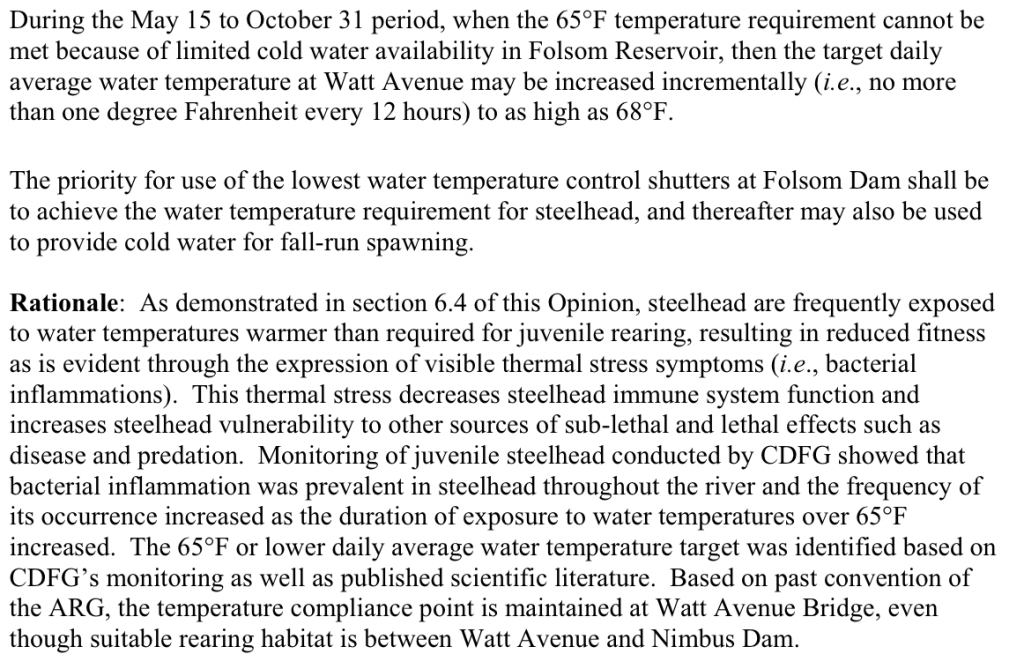

While regional water districts are screaming foul about the declining level of storage in Folsom and San Luis reservoirs, no one seems concerned about the American’s salmon and steelhead. We can understand (but not accept) the sacrifices in the extremes of the 2012-2015 drought (Figure 2), but not in 2016 a normal water year for the American River (Figure 3). Because Reclamation has drawn down Folsom Reservoir too far even in 2016, it lost the ability to use the available cold-water pool to maintain downstream cool river water temperatures (Figure 4). Also because Reclamation drew down the reservoir level, it allowed a provision for extreme conditions to kick in: an allowed increase in the water temperature requirement from 65°F to 68°F at Watt Avenue (Figure 5). That change in the federal biological opinion for operation of Folsom Reservoir (Figure 6) is designed for extraordinary circumstances and should not have occurred in 2016.

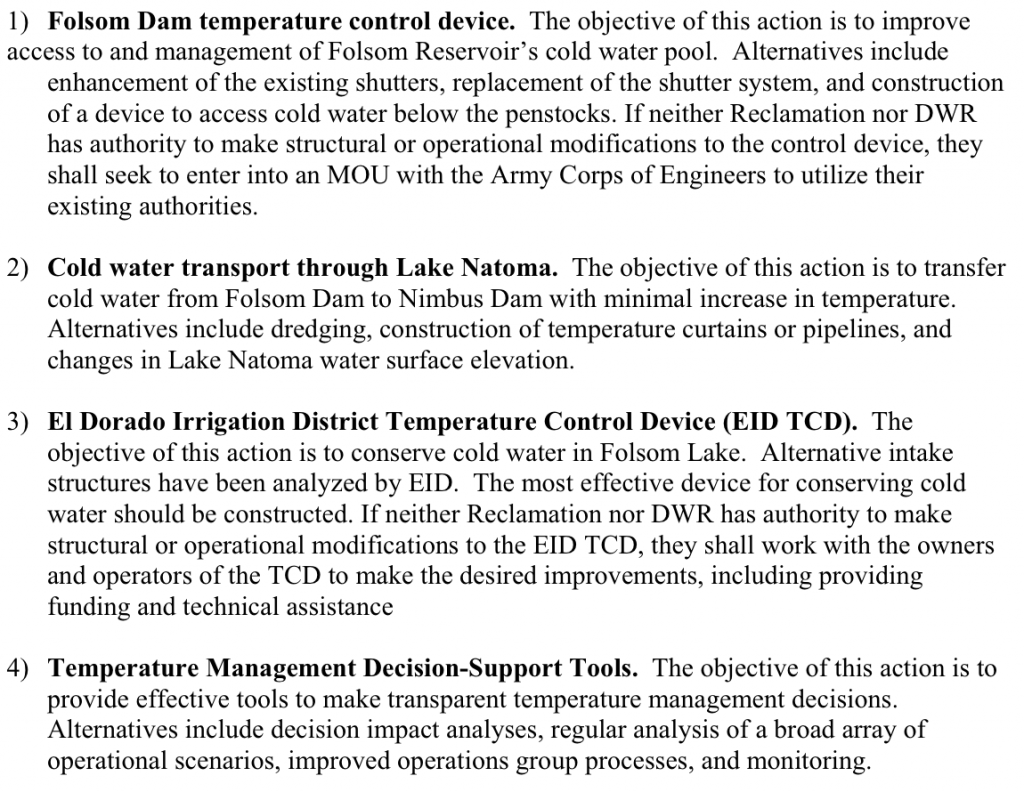

Reclamation has also made little progress toward other requirements to fix the Folsom problem (as shown in Figure 7).

After four years of drought and the mismanagement of Folsom Reservoir this summer by Reclamation, we can expect greatly reduced natural production of salmon and steelhead from the American River in the coming years.

For more information on this subject check out: http://www.safca.org/protection/NR_Documents/LARTF_2014_09_ Folsom_TCD_VPD_Ghoring.pdf .

Figure 2. Water temperature in the American River at William Pond Park at the downstream end of the river’s spawning reach in 2015. Red lines depict water temperature objectives set for salmon and steelhead spawning and rearing.

Figure 3. Water temperature in the American River at William Pond Park at the downstream end of the river’s spawning reach in 2016. Red lines depict water temperature objectives set for salmon and steelhead spawning and rearing.

Figure 4. Water temperature of water released from Folsom Reservoir April-August 2016. Red line is maximum temperature objective. Note July 13 attempt to release water from lower colder-water level outlet.

Figure 5. Water temperature in the American River at Watt Avenue in 2016. Green line is normal objective. Red line is relaxed standard for drought years.

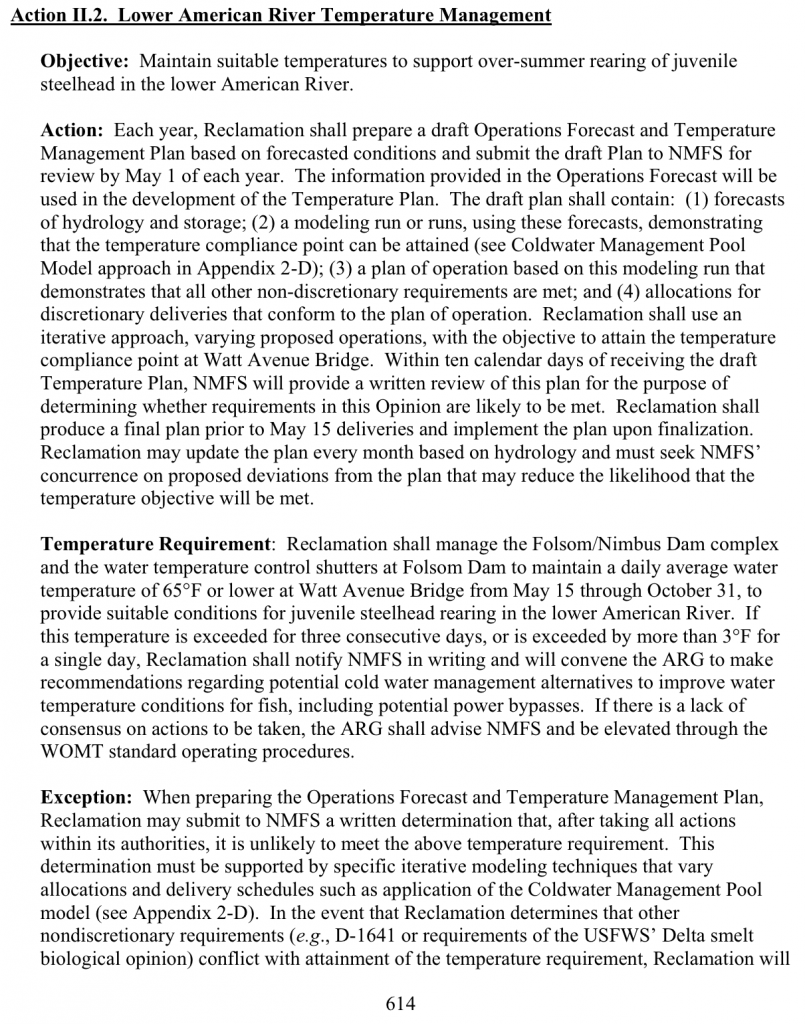

Figure 6. NMFS Biological Opinion excerpt from p615.

Figure 7. NMFS Biological Opinion excerpt from p616.