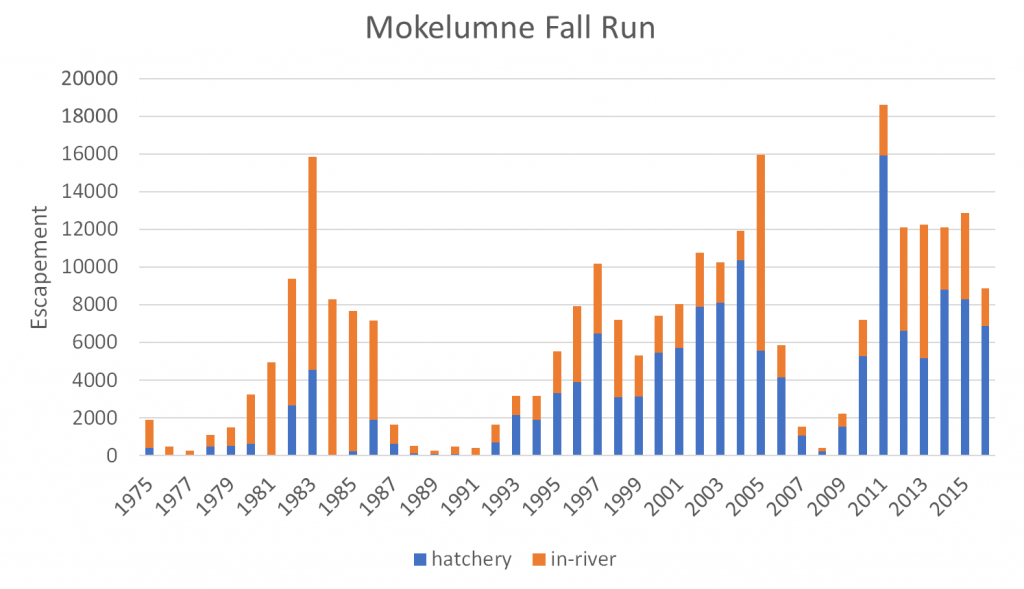

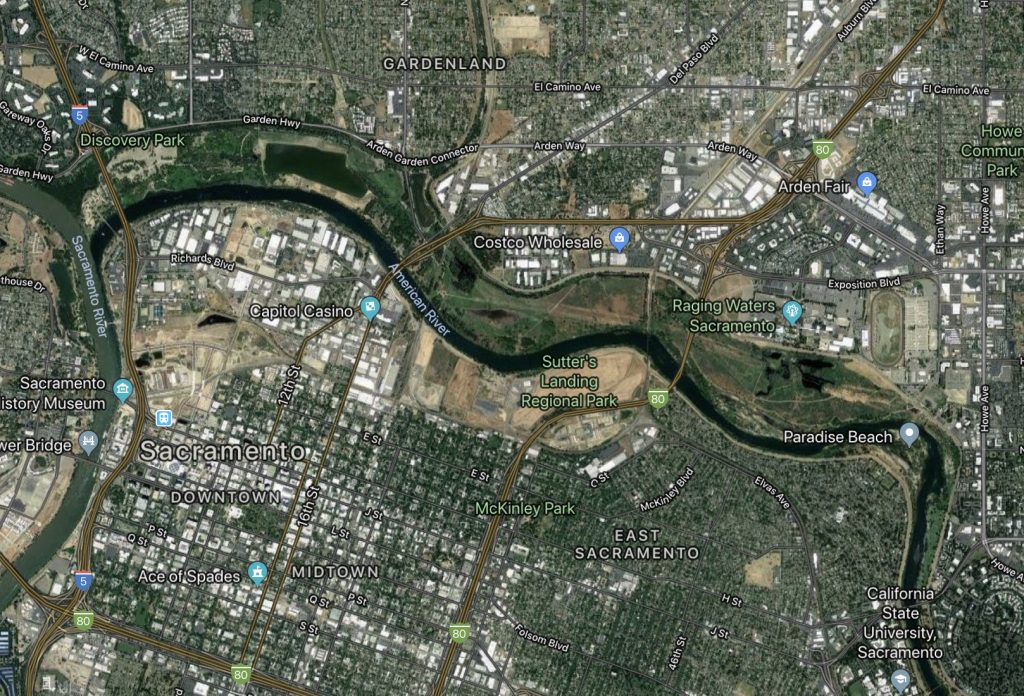

Figure 1. Lower American River floodplain referenced in recent science paper as non-natal rearing habitat of endangered winter-run Chinook salmon. Note the many borrow pits from Paradise Beach downstream to Discovery Park, remnants of a historical levee-building era.

Conundrum: A confusing and difficult problem.

The consulting firm FishBio reported in a February 12, 2018 blog post: “Just when you think you’ve got a species figured out, sometimes they show up where they’re “not supposed to be” and make you reconsider. This recently happened in the fish world, when adult winter-run Chinook salmon, an endangered fish previously thought to only inhabit the mainstem Sacramento River downstream of Keswick Dam, were found to have actually reared in multiple Sacramento River tributaries as juveniles.” The study referenced by FishBio found that roughly half of the returning adult winter-run had reared as juveniles for a several weeks or more in habitats other than the mainstem Sacramento River. It has long been known that winter-run had used these habitats1, but the proportion of the population that had done so was not known. The recent study has helped answer that question. Such a life-history pattern is obviously important, as proven by this study.

Juvenile winter-run salmon have frequently been detected in winter in habitats along the Sacramento River from Redding to Rio Vista in habitats where they are not commonly expected to be. In wet years, winter-run are carried into the Butte-Sutter and Yolo bypasses (and other Sacramento River floodplain areas like the lower American River) where they rear as noted in the recent study. I personally have collected large numbers of winter-run juveniles in the 1990’s in Butte Basin, the Bypasses, and the lower American River floodplain (Figure 1). In many cases, floods had carried or backed-up water along with winter-run juveniles into these areas. I have also collected winter-run juveniles (and other juvenile fall/spring salmon) in Suisun Bay, downstream of the Delta. A 2013 report by biologist Michael Healey of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife found that winter-run migrate up Auburn Ravine in Sutter County to rear.2

“These newly identified areas, called “non-natal habitats” because they differ from where the fish was born, can be divided into four distinct groups, including the Mount Lassen tributaries (Mill, Deer, and Battle creeks), the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta and Feather River, the American River, and a final group rearing in an uncertain location that is not in the Sacramento River.” Again, these are not “newly” identified. Non-natal refers to rearing in adjacent river systems where fish were not born. These habitats are part of the lower Sacramento River floodplain and other accessible habitat of winter-run.

“So even though we might think winter-run are “not supposed to be” using these tributaries, the fish are actually spreading the risk of extinction across multiple habitats to safeguard their future.” These are the natural floodplain and tributary rearing habitats of winter-run. The problem is that there is not enough of these habitats left, and those that are left are often too ephemeral or are in poor condition. In many cases, the young salmon are gain access to floodplains but are later blocked from exiting, only to eventually die and not contribute to the population. Juveniles that enter the lower reaches of tributaries of the Sacramento River are sometimes cut off by seasonal dams or stranded in fields by unscreened irrigation diversions. Often, non-natal habitats (e.g., dredger ponds and borrow pits) are also winter refuges and permanent habitat for predatory warm water fish.

Yes, these non-natal rearing habitats should be recognized, protected, restored, fixed, enhanced, and created where possible to help save the winter-run salmon population. In the meantime, such habitats will continue to support winter-run as they have in the past. There is no “conundrum”.

- P.E. Maslin, W.R. McKinney, T.L. Moore. 1996. Intermittent streams as rearing habitat for Sacramento river Chinook salmon. Anadromous Fish Restoration Program, Stockton, CA, United States Fish and Wildlife Service (1996), pp. 1-29 ↩

- https://plummerj.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/healey-cdfw-2013-auburn-ravine-rotary-screw-trap-monitoring-report-rs.pdf ↩