Reports1 indicate strong runs of fall Chinook salmon on the Mokelumne, American, and Feather rivers this fall. The success is generally attributed to better management of hatcheries, project operation (flows), and habitat restoration. The most logical explanation is that hatcheries transported their salmon smolts to the west Delta and Bay for release in recent years. During the 2012-2015 drought, most Valley hatcheries trucked their smolts to the Bay or Delta. Trucking in 2014-2015 likely led to the high numbers returning this fall, including the large number of strays from the Battle Creek hatchery near Redding. The straying among the hatcheries is problematic but manageable (the American and Mokelumne hatcheries shipped eggs to the Battle Creek hatchery this year). The runs also have benefitted from spawning and rearing habitat restoration over the past two decades. The Mokelumne success story is somewhat unique in that restoration efforts have been more intensive and diversified, and the hatchery program has been more progressive in a number of aspects (e.g., transporting smolts via barge).2

The Mokelumne Hatchery program has so many new elements it is hard to say which has been most effective. The run has steadily increased. However, most of the adult escapement, including in-river spawners, is of hatchery origin. Besides all the straying, many fish scientists and managers remain concerned about the dominance of the hatcheries and lack of wild fish recovery throughout the Central Valley. Can the dam-free rivers without hatcheries retain wild salmon populations with all the hatchery strays “polluting” their gene pools? Do hatcheries bring complacency and lead to lack of protections for wild fish and their habitats? These are tough questions. However, one thing is for sure: given the dominance of hatchery salmon, it is safe to say there would be far less salmon and few salmon fisheries in California without the hatcheries. Some “wild” salmon rivers may not even have significant salmon runs without hatcheries hatchery strays (e.g., Yuba, Putah, Cache, Cosumnes, Calaveras, San Joaquin, Stanislaus, etc.).

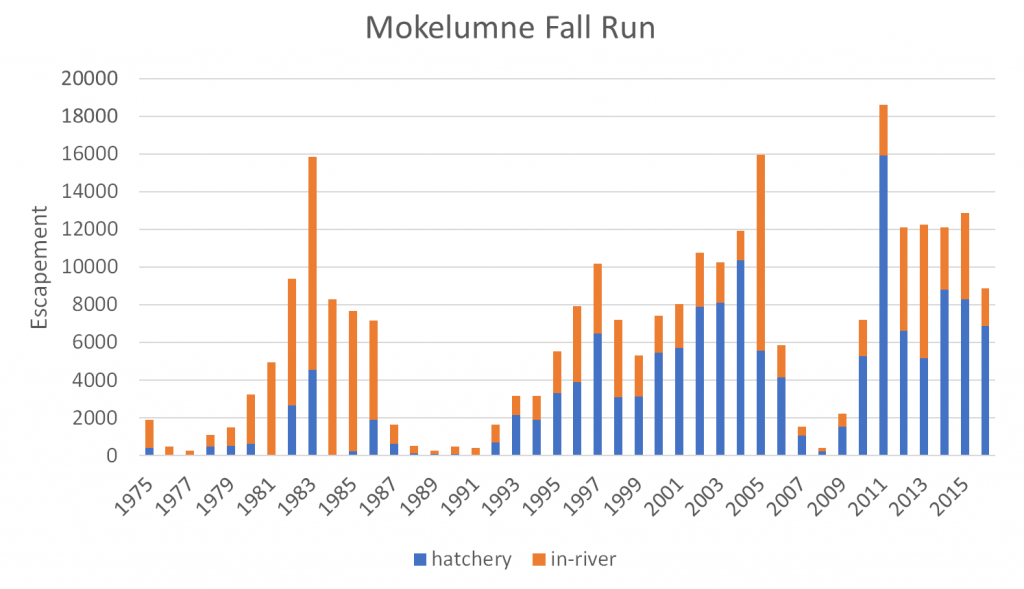

The importance and dominance of the hatchery program to the Mokelumne salmon run can be seen in the long term escapement estimates 1975-2016 (Figure 1). Note that the near record low run in 2008 led to the record high run in 2011. This reflects the fact it does not take a lot of salmon reaching the hatchery to produce enough smolts to produce a record run under high survival conditions for the smolts. In addition, with good survival and strong runs throughout the Valley in wet year 2011, there were high numbers of strays from other rivers that added to the Mokelumne run.

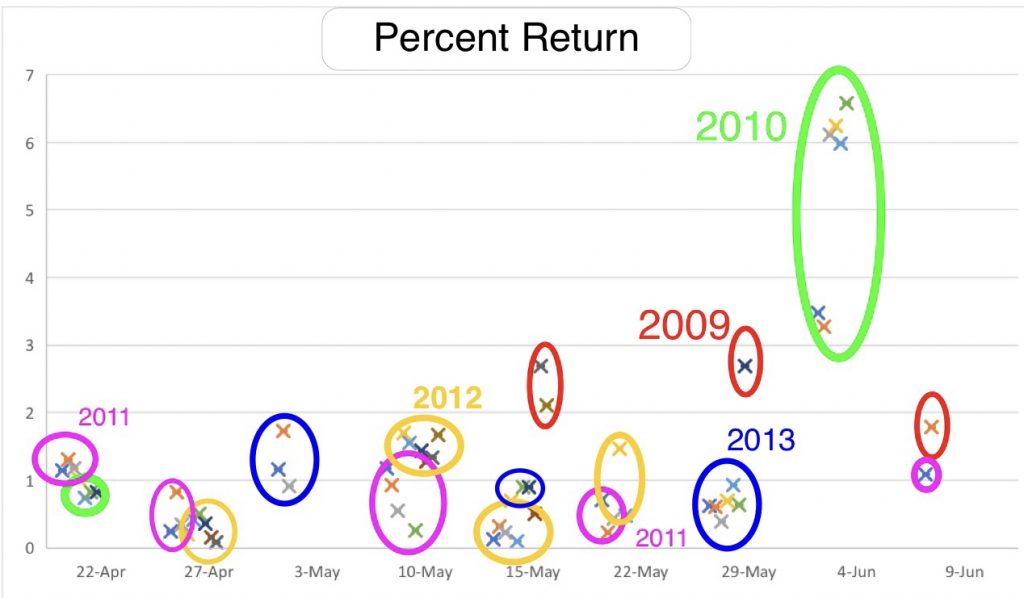

Analysis of historic coded-wire-tag return data for the Mokelumne hatchery smolt releases by release year indicates some reasonably good returns (>1%) for the recent 2009 to 2013 release years (Figure 2). Release years 2009 and 2010 were exceptional, with 2 to 6 % returns. This likely reflected the normal and wet water years of 2010-2012. Release years 2011-2013 generally had poor river and ocean rearing conditions as well as poor adult return and spawning conditions upon their return. Good survival for release years 2009 and 2010 likely contributed to the record run of adults and grilse (jacks – early return adults) in 2011.

While little tag return data for release years 2014-2016 are yet available, it is likely that the 2015 release had high survival on the order of the 2009 and 2010 releases to bring about the near record run in 2017. High 2017 returns may have occurred from a number of factors, including barging smolts and spring flow pulse in 2015, good river conditions in late summer and fall 2017, and good ocean conditions in 2016-2017.

Regardless of specific causal factor, it would seem that there are lessons to be learned from the Mokelumne River salmon management program. Further questions may be needed to get to the specific root factors in the Mokelumne success story (EBMUD and CDFW may already have the answers to these questions):

- What is the proportion of hatchery fish in the run? Since 25 % of the hatchery smolts are marked it should be possible to estimate the proportion of hatchery and wild river-born salmon in the adult run. With genetic sampling, the contribution of wild genes may also be determined.

- Which release groups were barged? (Not indicated in the RMIS database.)

- What were conditions in the Delta during and after releases?

- What were straying rates and conditions during adult runs? Were strays to other rivers including Putah Creek taken into account? What were contributions from other hatcheries? (Some answers can be gleaned from RMIS database.)

In summary, near record fall run salmon hatchery runs in 2017 indicates potentially increased hatchery contributions that could be built upon to improve salmon fisheries dependent on the Central Valley hatcheries.

Figure 1. Mokelumne River salmon run estimates for 1975-2016. (Source: Grandtab)

Figure 2. Percent survival to adult of Mokelumne hatchery smolt releases near Sherman Island in the west Delta in spring of years 2009 to 2013. Source of data: http://www.rmis.org/

- http://www.kcra.com/article/mokelumne-river-fall-run-salmon-approach-record-high/13791027

http://www.sfchronicle.com/news/article/Salmon-population-booms-on-state-s-Mokelumne-12364274.php

http://goldrushcam.com/sierrasuntimes/index.php/news/local-news/11932-chinook-salmon-returns-on-mokelumne-river-continue-record-streak ↩ - http://www.eastbaytimes.com/2017/11/17/innovative-measures-steer-central-valley-salmon-run-near-record/ ↩