So much is at stake in this water year 2022: water supplies, water quality, agricultural production, hydropower production, as well as the future of salmon, steelhead, sturgeon, smelt, and other native fishes of the Klamath and Sacramento-San Joaquin watersheds. Despite the lessons of the 1976-1977, 1987-1992, 2007-2009, and 2013-2015 droughts, the choices and tradeoffs are more difficult, and effects more significant and consequential to the fish, in 2022, the third year of the 2020-2022 drought. The State Water Resources Control Board is about to approve 2022 water operation plans for Central Valley Project (CVP) and the State Water Project (SWP). Among the most immediate effects of these plans will be the fate of iconic fisheries resources of the Sacramento and Klamath Rivers, in 2022 and beyond.

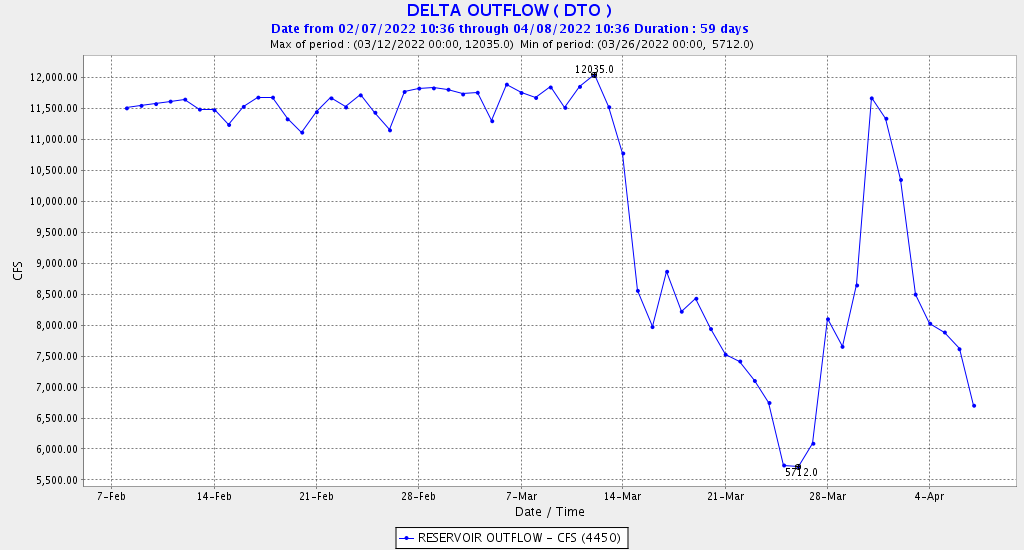

The two key elements of the plans are (1) the Sacramento River Temperature Management Plan (TMP) governing Shasta/Trinity operations, and (2) the Temporary Urgency Change Petition (TUCP) governing Delta operations. A 4/5/22 post covered some aspects of the TUCP on Delta operations, which serves to cut demands on federal and state reservoir storage in the Sacramento River watershed by lowering Delta outflow requirements. (See also CSPA and allied organizations’ protest and objection to the TUCP.)

This post covers the 2022 TMP, which focuses on Shasta/Trinity storage releases and management of Shasta Reservoir’s storage releases and cold-water pool in support of Sacramento River salmon. It starts with a review of both the hydrological and biological effects of Shasta and Trinity operations in 2021. Starting with 2021 creates context in two ways. First, it explains the severe depletion of CVP and SWP storage in 2021, which created the avoidable portion of the extreme storage conditions of 2022. Second, it describes the disastrous failure to protect fish in 2021, both as consequence of bad management and contributor to the dire conditions of fisheries in 2022.

2021 Sacramento River Operations

The predominant characteristic of 2021’s operations of Shasta Reservoir and the Sacramento River was excessive reservoir storage releases over the spring and summer for water deliveries. Within this constrained context, the dominant biological features in 2021 were management of the cold-water pool for salmon , along with associated “downstream” effects on the lower river and Bay-Delta. The 2021 Sacramento River operations plan led to significantly reduced production in brood year 2021 of all four runs of Sacramento salmon.

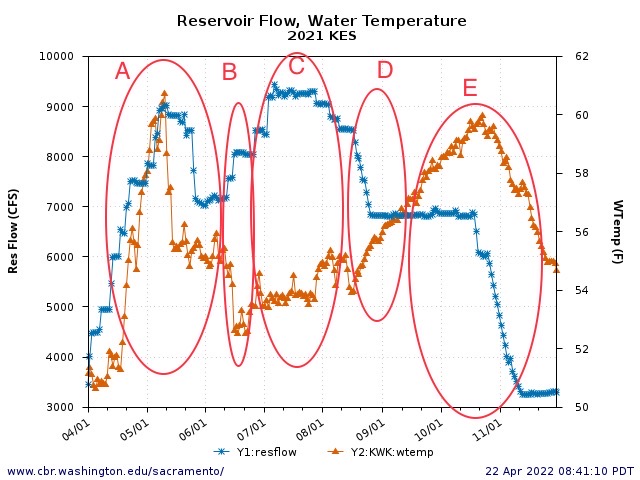

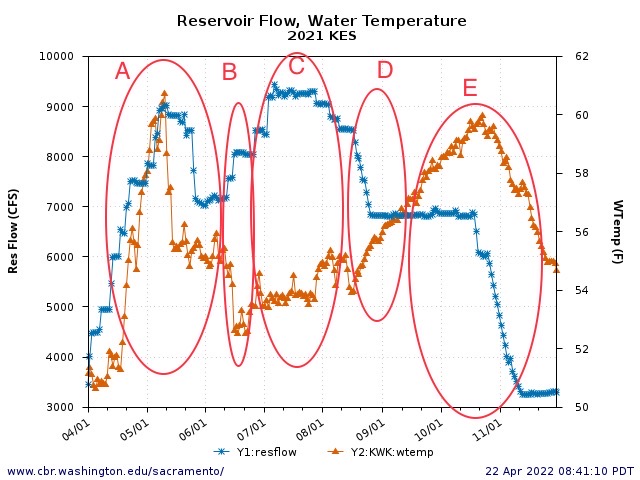

I have divided the 2021 story into five event periods (Figure 1), each with differing conditions and outcomes:

Period A: The early-April through early-June period was characterized by rapidly rising high releases (6000-9000 cfs) for water deliveries in late April and May. Reclamation claimed it saved 300 TAF of Shasta’s cold-water pool using power bypass of warm surface water for the high spring releases. In reality, the excessive delivery of irrigation water unnecessarily depleted total Shasta storage by nearly 500 TAF and depleted the cold-water pool by 200 TAF. Those storage losses also crippled any ability to subsequently sustain the cold-water pool through the summer.

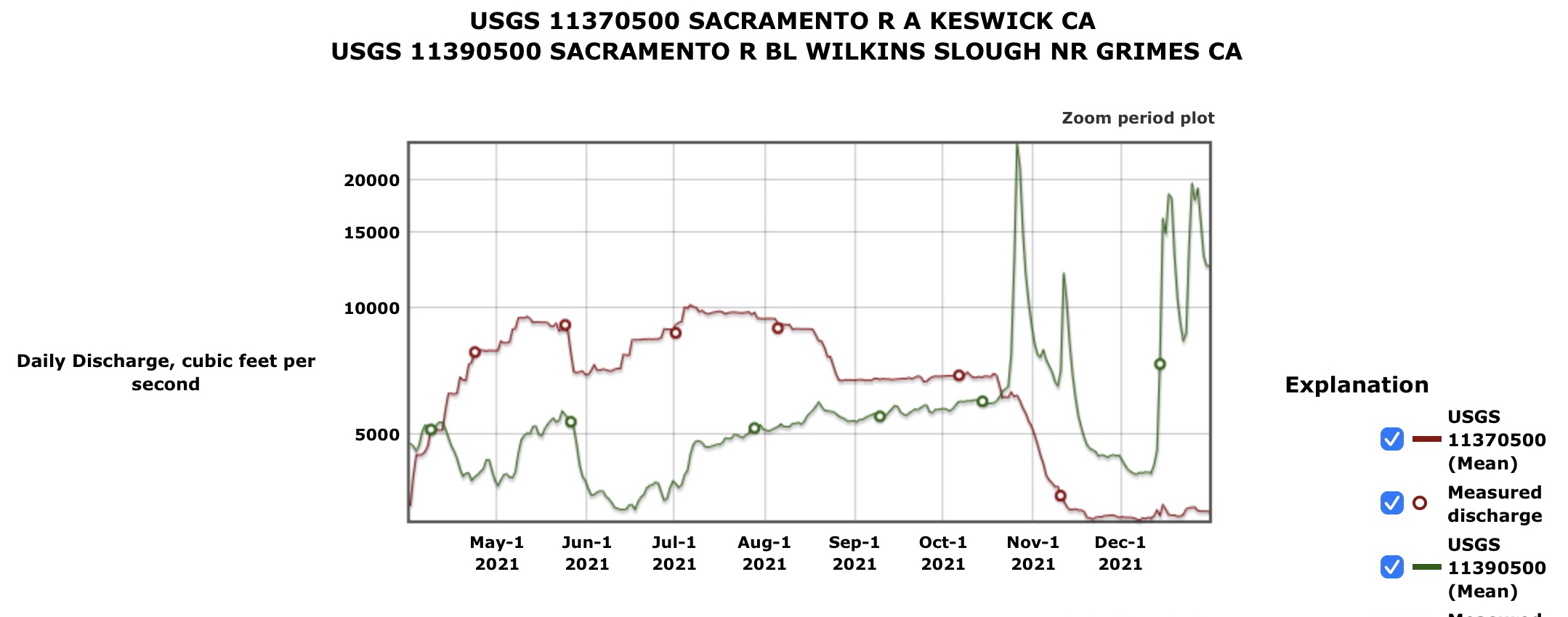

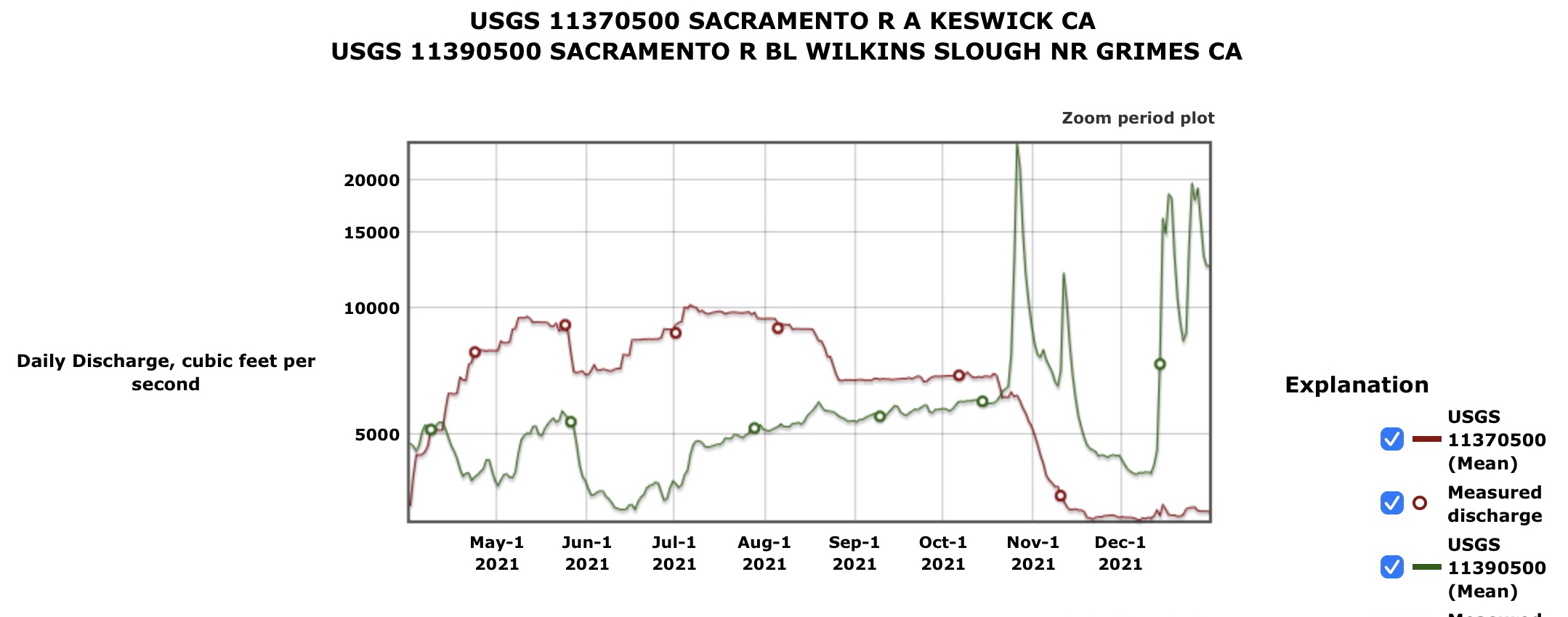

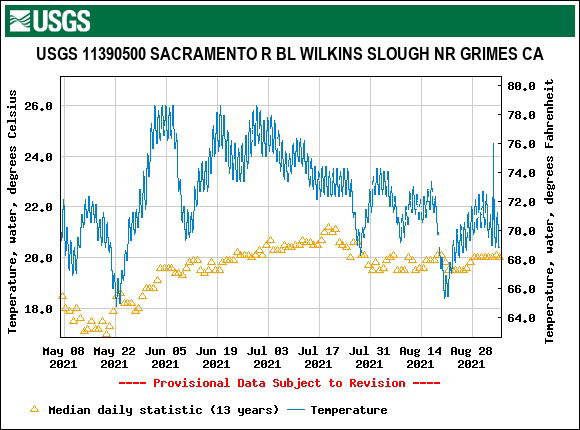

The releases of unseasonably warmer water (56-60ºF) also (as planned) inhibited spawning in the late-April to early-June portion of the winter-run salmon spawning season (about half of the historical season). It also stressed winter-run and spring-run adults in their upper river pre-spawn holding areas. Recent scientific studies suggest that such stress (extended holding and warmer water) may have contributed to thiamine deficiencies in spawners that contributed to poor subsequent fry survival and smolt production. Rapidly rising flows and water temperatures may have also compromised late-fall-run salmon egg incubation that normally continues into April. Irrigation deliveries in the middle and upper river led to lower flows and high water temperatures in the lower river (Figures 2 and 3); this both reduced the survival of emigrating spring smolts of all four races of salmon, and hindered and stressed upstream migrating winter-run and spring-run adults.

Period B: The mid-June period of cold-water releases (53-55ºF) was designed to stimulate winter-run adult spawning. It also provided 8000 cfs irrigation releases that unnecessarily depleted total storage and the cold-water pool by 6-8 TAF per day for nearly two weeks (~100 TAF lost cold-water pool and total storage). It also resulted in salmon spawning at 8000 cfs, spawning habitat conditions that led to water surface elevations that increased by one-foot and then dropped by two-feet over the summer salmon egg incubation season. I have not assessed the role of flow on the amount of quality spawning habitat available or on the potential of redd dewatering/stranding, although such factors should also be considered in evaluating an operations plan. Irrigation deliveries in the middle and upper river led to lower flows and high water temperatures in the lower river (see Figures 2 and 3), hindering and stressing winter-run and spring-run adults that were late in migrating upstream.

Period C: The late-June to early-August period was the main winter-run egg incubation period under 2021 operations. Flow releases increased to accommodate irrigation demands. Irrigation diversions, in turn, reduced flows in the river further downstream, leading to high water temperatures (72-78ºF) that blocked early arriving fall-run adult immigrants. A rise of almost two feet in water level in early June from the increased flow likely caused some redd scouring in the upper river spawning reach below Keswick Dam.

Period D: The mid-August to mid-September period was characterized by falling storage releases, associated declining water levels, and warming water as the cold-water pool and access to it declined. Winter-run egg incubation continued through the period and likely suffered from stressful water temperatures and redd dewatering. Flows in the lower river increased, and water temperatures declined, becoming less stressful for upstream migrating adult fall-run.

Period E: The late-September through November period was characterized by continued warming of water temperatures due to lessening access to Shasta’s severely depleted cold-water pool, followed by natural fall cooling. Releases and water levels declined rapidly in the spawning reach. At the beginning of the period, warm water interrupted or delayed spring-run and fall-run spawning, while a water level drop of several feet led to redd dewatering and stranding. Winter-run fry were also subjected to potential stranding during the drop in water level. Spring-run and fall-run spawning was likely hindered or delayed into November due to high water temperatures and decreasing flows and associated water levels.

The 2022 Plan

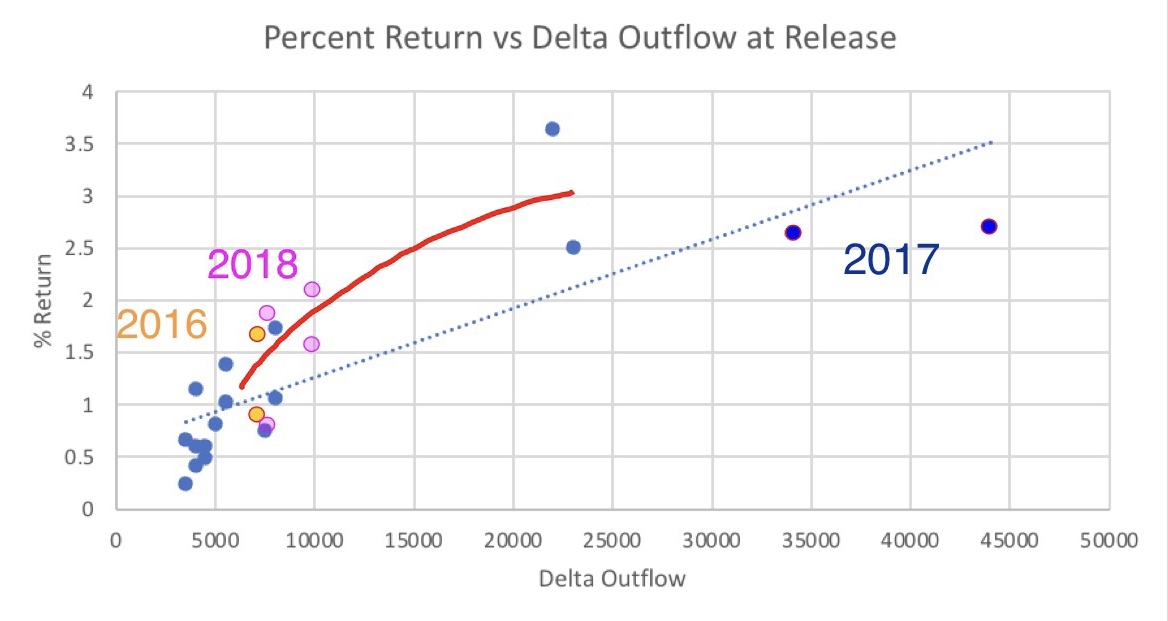

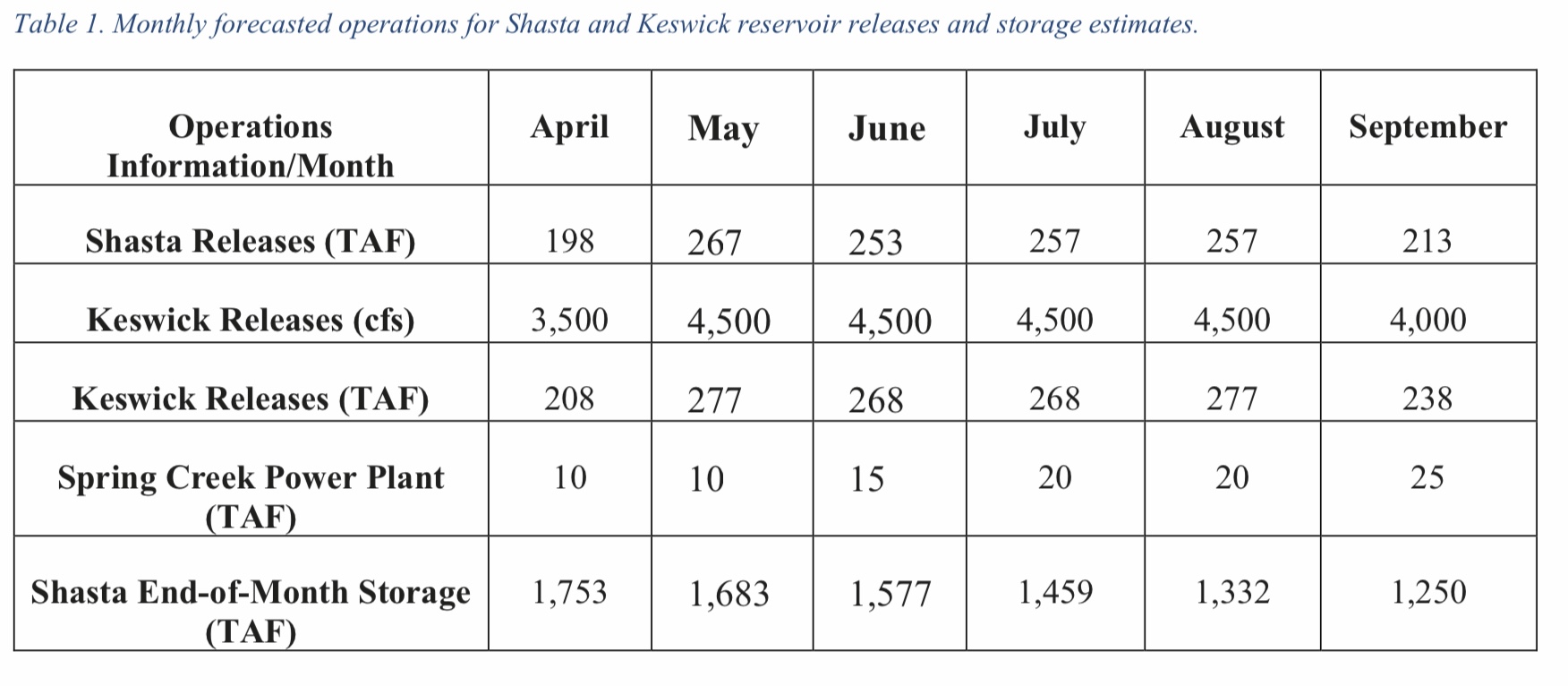

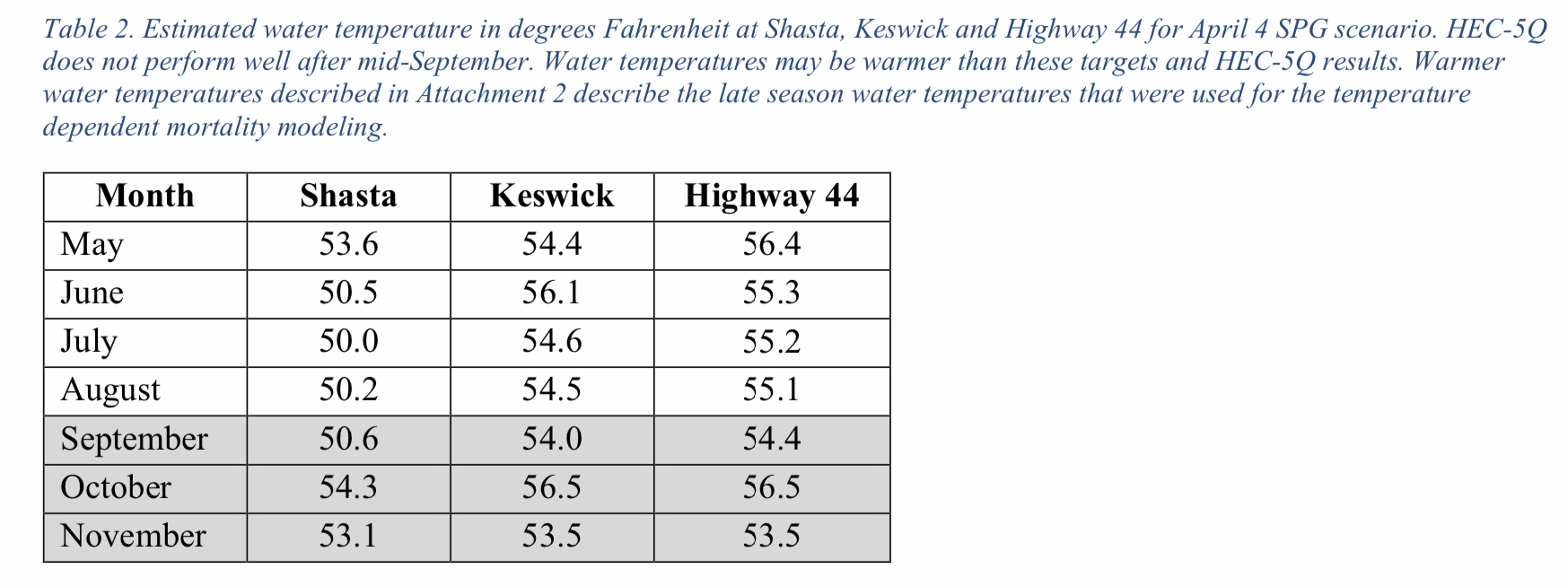

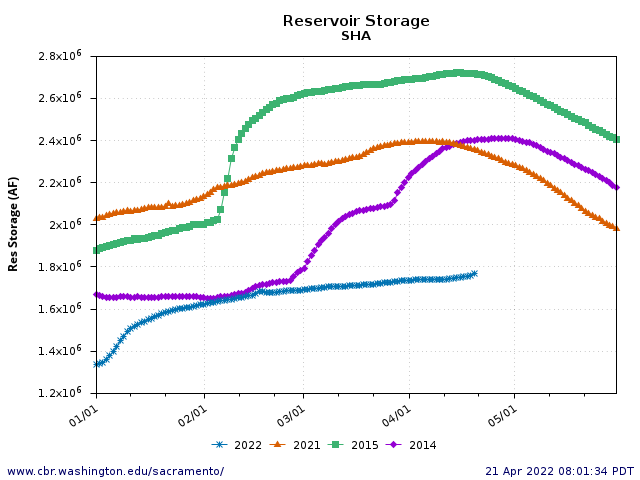

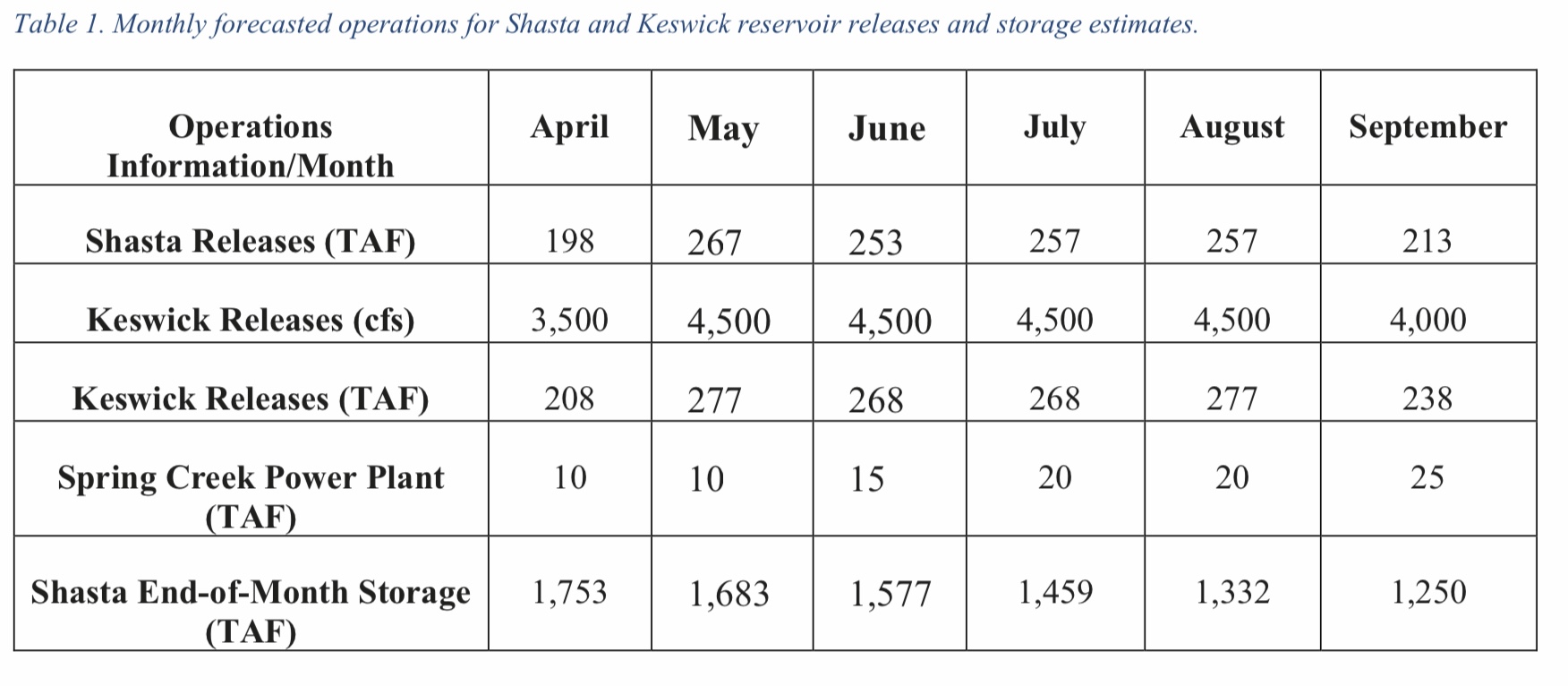

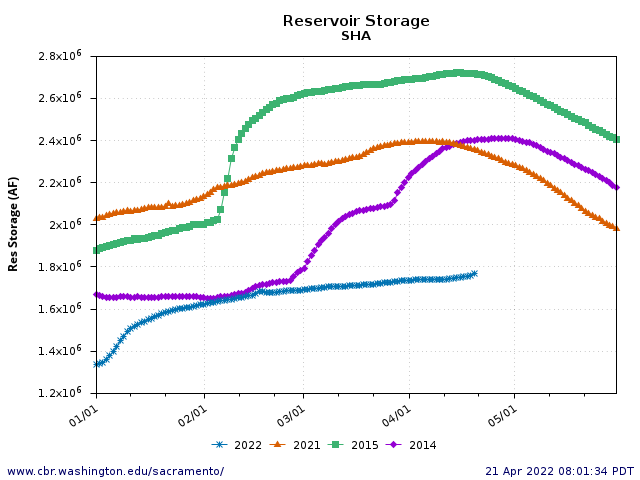

The May 2 2022 Final TMP Is a radical change from the 2021 plan and actual operations. For the first time, Reclamation has prioritized protection of fish over irrigation deliveries to senior Sacramento River Settlement Contractors. The changes also reflect the much lower available storage in this third year of drought (Figure 4). Water release projections are much lower to sustain the cold-water pool and cool downstream temperatures through the summer (Tables 1 and 2).

April Operations and Effects

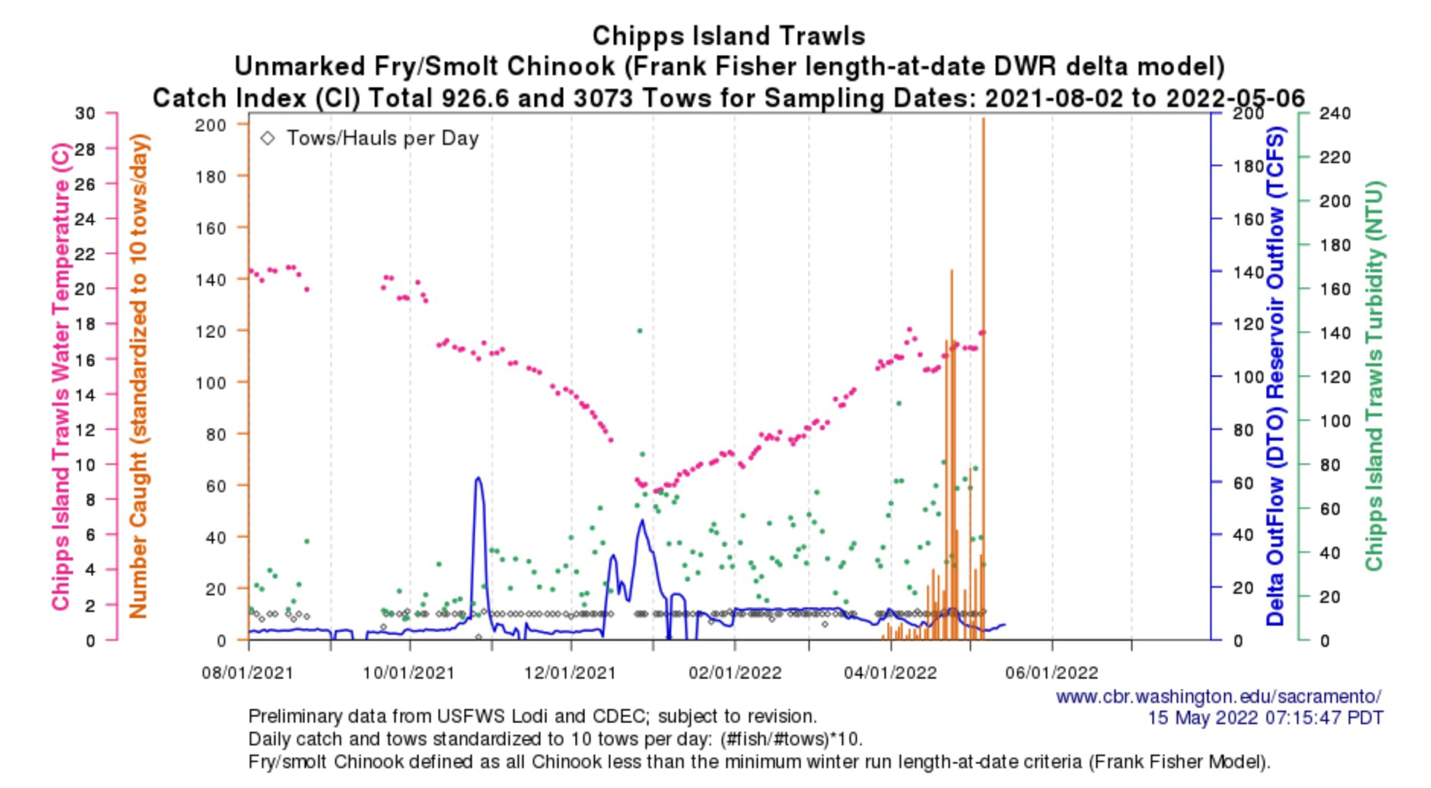

April operations closely followed the draft plan that Reclamation submitted to the State Water Board on April 6. April operations using middle TCD gates and small imports of Trinity River water maintained Keswick releases at 52-53ºC and 3250 cfs per the draft 2022 TMP. Such operation helped preserve Shasta storage and the volume of the deeper, cold-water pool (<50ºF). Valley-wide precipitation since mid-April increased flows in the middle and lower Sacramento River, stimulating juvenile salmon emigration and adult spring-run and winter-run salmon immigration. A small pulse flow from Keswick to the 30 miles of spawning and rearing habitat below Keswick Dam would have helped stimulate and benefit these salmon migrations, especially those from the upper 30-mile reach that saw little or no benefits from the April storms, but this did not occur.

The draft TMP (April 6) had the same proposed releases from Keswick Reservoir as the final TMP (May 2). However, the end-of-September storage in Shasta Reservoir predicted in the final TMP (1135 TAF) is over 100 TAF lower than was the prediction in the draft TMP (1250 TAF).

Proposed May Operations

The proposed May 4500 cfs release would come from Shasta Dam’s middle gates with access to warmer surface water in the lake, thus saving some of the cold-water pool. Such savings would require warmer releases that would delay spawning and stress holding adult winter-run and spring-run salmon.

For those winter-run who do spawn in May, egg survival could be compromised by the warmer water. With warming surface waters and warmer reservoir inflows in May, and more pre-spawn adult salmon arriving in the 10-mile spawning reach below Keswick Dam, a Keswick release temperature maintained at or below 51ºF would ensure the 10-mile spawning and holding reach is maintained near 53ºF. A colder release would require proportionately more cold water be released from deeper dam gates.

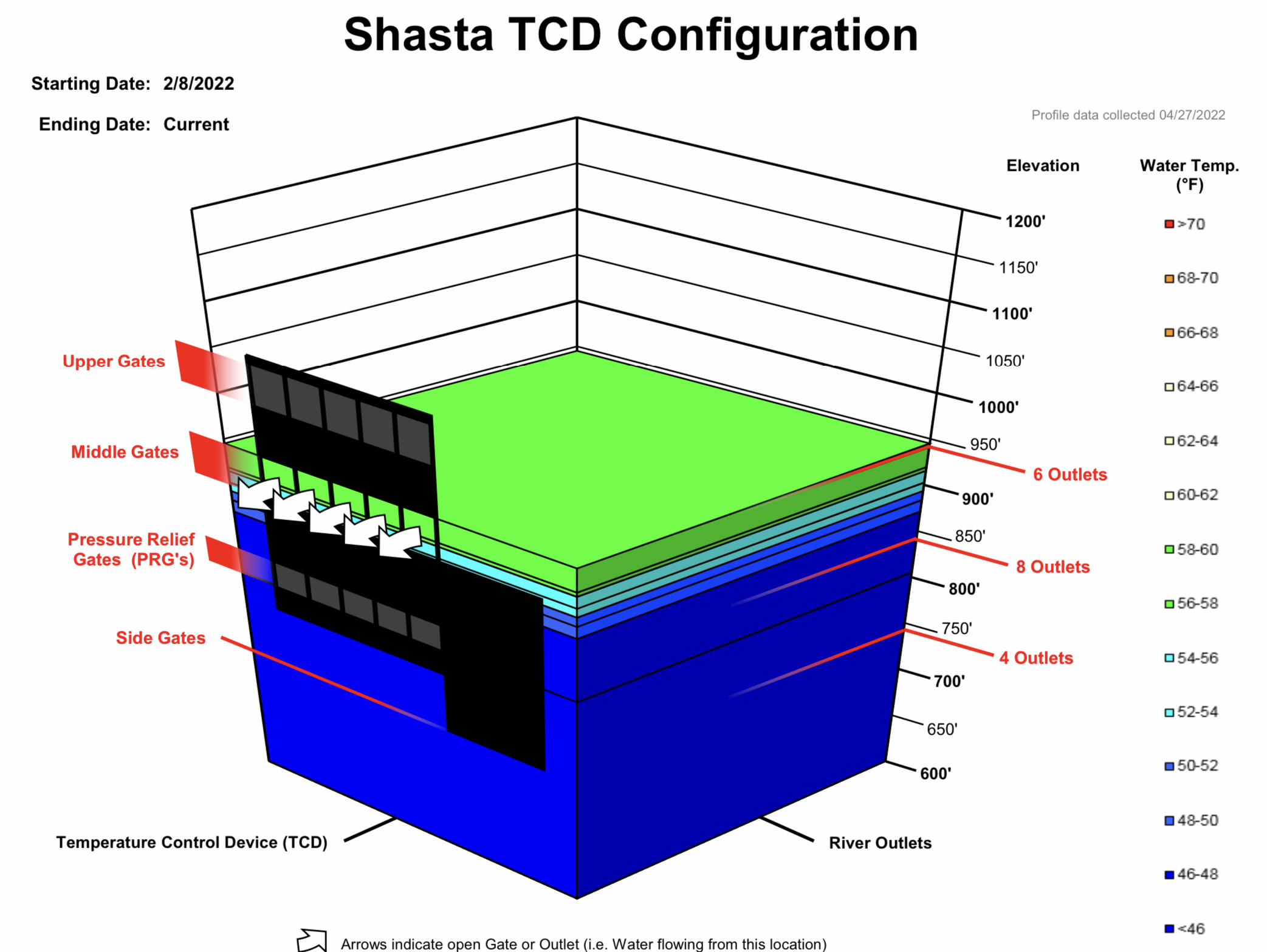

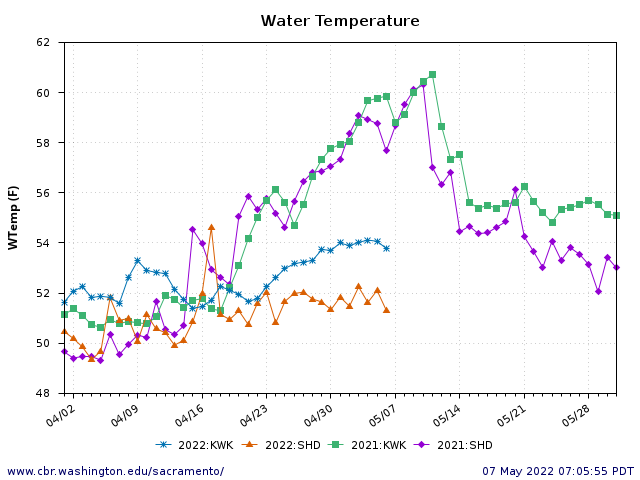

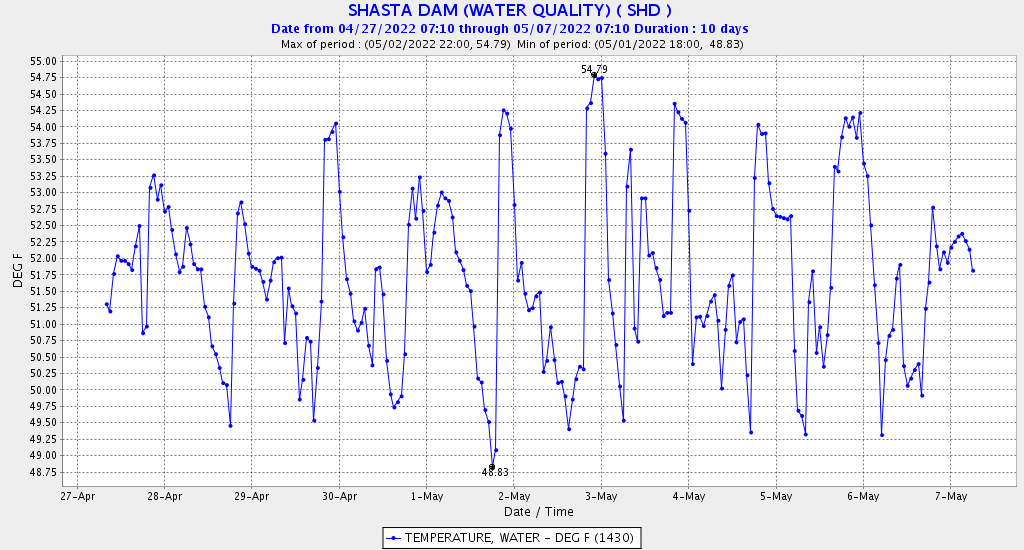

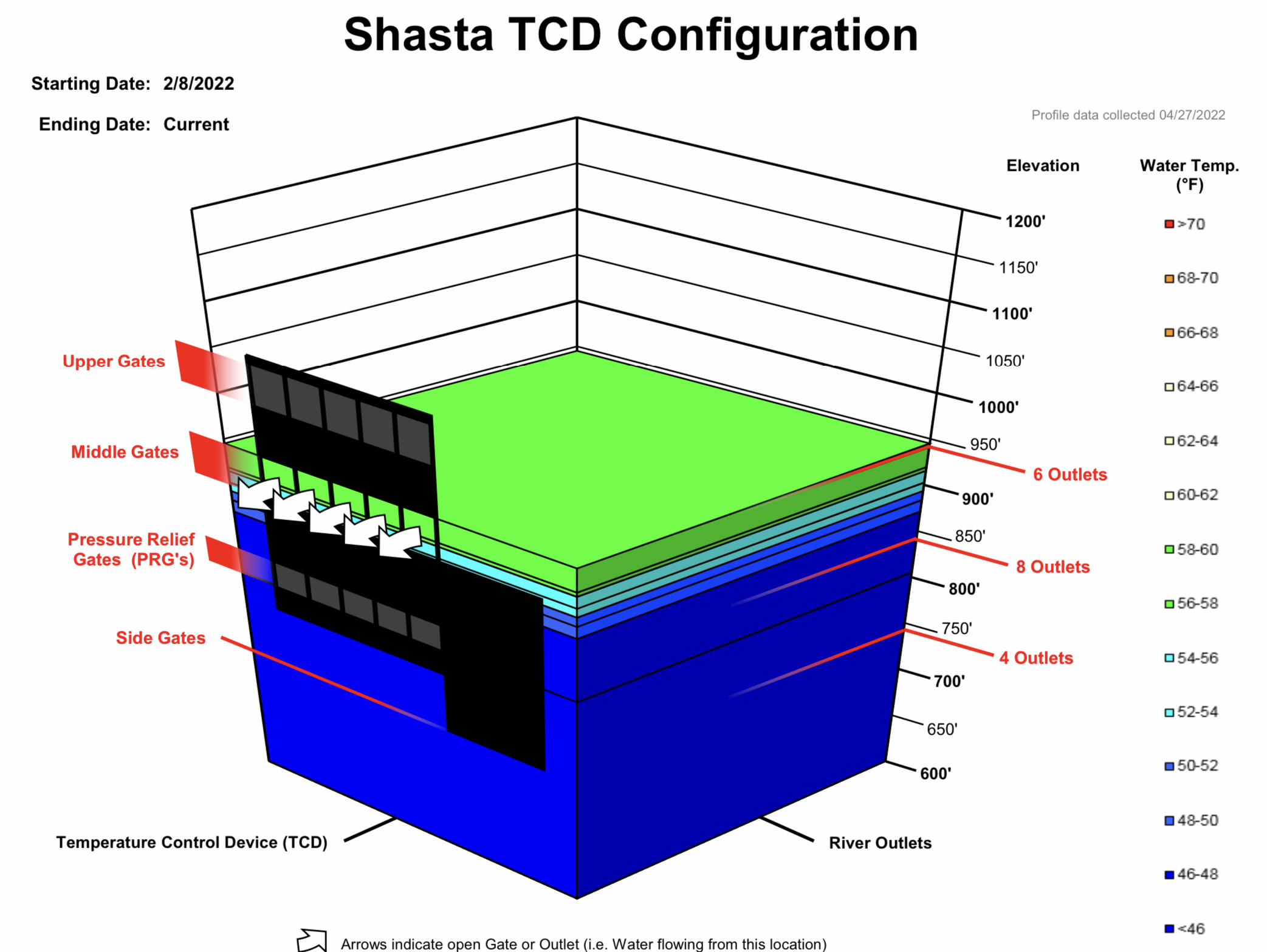

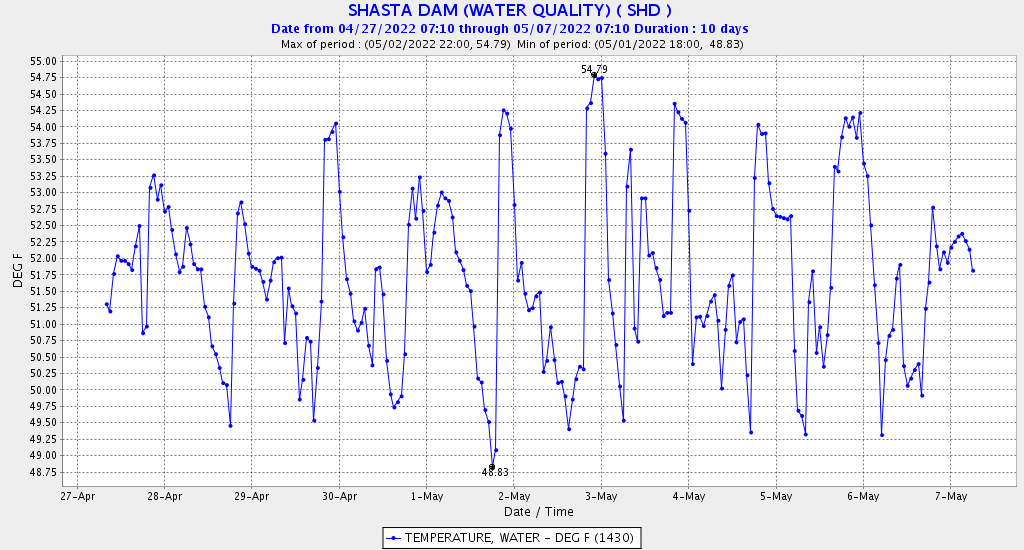

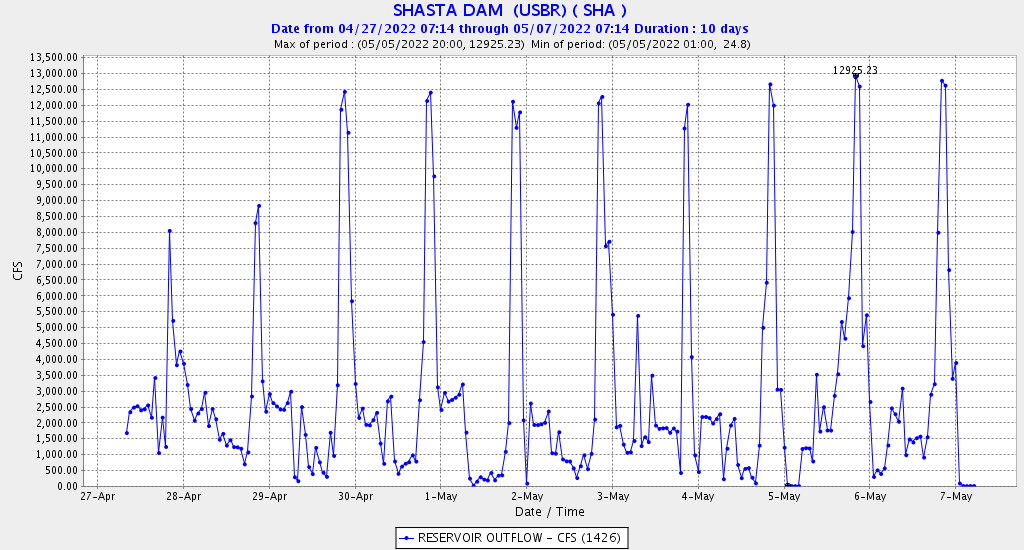

In reality, middle gate operation through early May (Figures 5 and 6) has sustained cooler-than-expected daily-average release temperatures at 51-52ºF. Hydropower peaking has accessed the warmer upper layers of the reservoir (Figures 7 and 8), saving some of the cold-water pool as planned. However, middle-gate operation under hydropower peaking, and gradual warming of reservoir surface waters, will result in increasing release temperatures per the plan later in May. A rapidly warming reservoir may necessitate use of lower gates or less hydropower peaking operations to maintain <54ºF through May per the plan. If spawning commences in early May due to cooler than planned dam releases, higher late May release temperatures would begin to compromise earlier-spawned egg survival. This should cause some re-evaluation of the plan.

Proposed June-September Operations

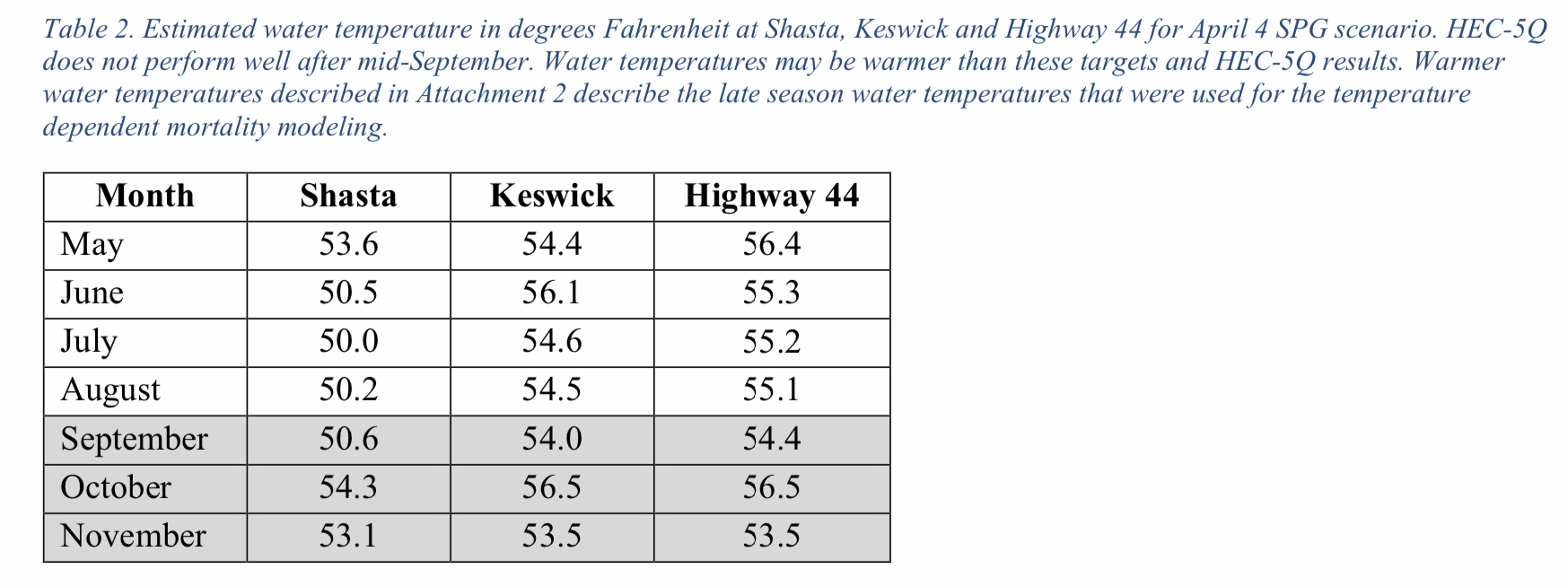

The proposed June-September 4500 cfs release (4000 cfs in September) from Shasta Dam will be from the lower TCD gates from the cold-water pool at ~50ºF (Table 2). Slightly higher Keswick Dam release water temperatures are predicted due to warming in Keswick Reservoir at ~4500 cfs through-flow. Water temperatures 5 miles downstream at Highway 44 will increase slightly more due to warm air temperatures.

The final temperature management strategy, based on recommendations received from the Sacramento River Temperature Task Group (SRTTG), is to target 58ºF at Highway 44 during the initial part of the season and then target 54.5ºF for 16 weeks around the estimated peak spawning date of Aug 2. This would result in targeting 54.5ºF from June 7 through September 27 or until the cold water is used up. Due to the limited available control in operating the middle gates (as described above), temperatures in June and July may be cooler than 54.5ºF. Reclamation will operate the TCD to target as close as possible to 54.5ºF to conserve cold water for maintaining target temperatures throughout the critical period.

Reclamation also received feedback from SRTTG members that an initial target of 58ºF would help to conserve cold water for later during the more critical portion of the temperature management season. The problem with this is that it will delay spawning, stressing yet-to-spawn adults and compromising survival of earlier-spawned embryos.

Fall Operations

Fall operations will be similar to those described above for Period E in 2021, with the exception of a lesser drop in flow. Water temperatures in late summer and fall will increase as the cold-water pool is depleted and access to it ends. Increasing temperatures will delay spring-run and fall-run spawning and stress pre-spawn adults (potentially aggravating the thiamine deficiency problem).

Uncertainties

The planners have noted significant uncertainties that will require intensive real-time operations and management throughout the summer to achieve the various goals and targets throughout the system. To address uncertainty, Reclamation has employed conservative estimates of future conditions in the modeling assumptions (e.g., hydrology, operations, and meteorology) and projections, and has included as part of the TMP the potential to make changes, in consultation with the SRTTG, Water Operations Management Team, and/or the Shasta Planning Group. The State Board and NMFS should be included in the decision process.

Infrastructure limitations

The 2022 TMP was developed in consideration of the limitations on using the TCD and the need for temperatures below 56ºF at the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery. Efforts to address these limitations should be accelerated. Hydropower peaking operations changes should also be considered.

Related Actions to the Final 2022 TMP

1. Six-Fold Increase in Winter-Run Hatchery Smolt Production

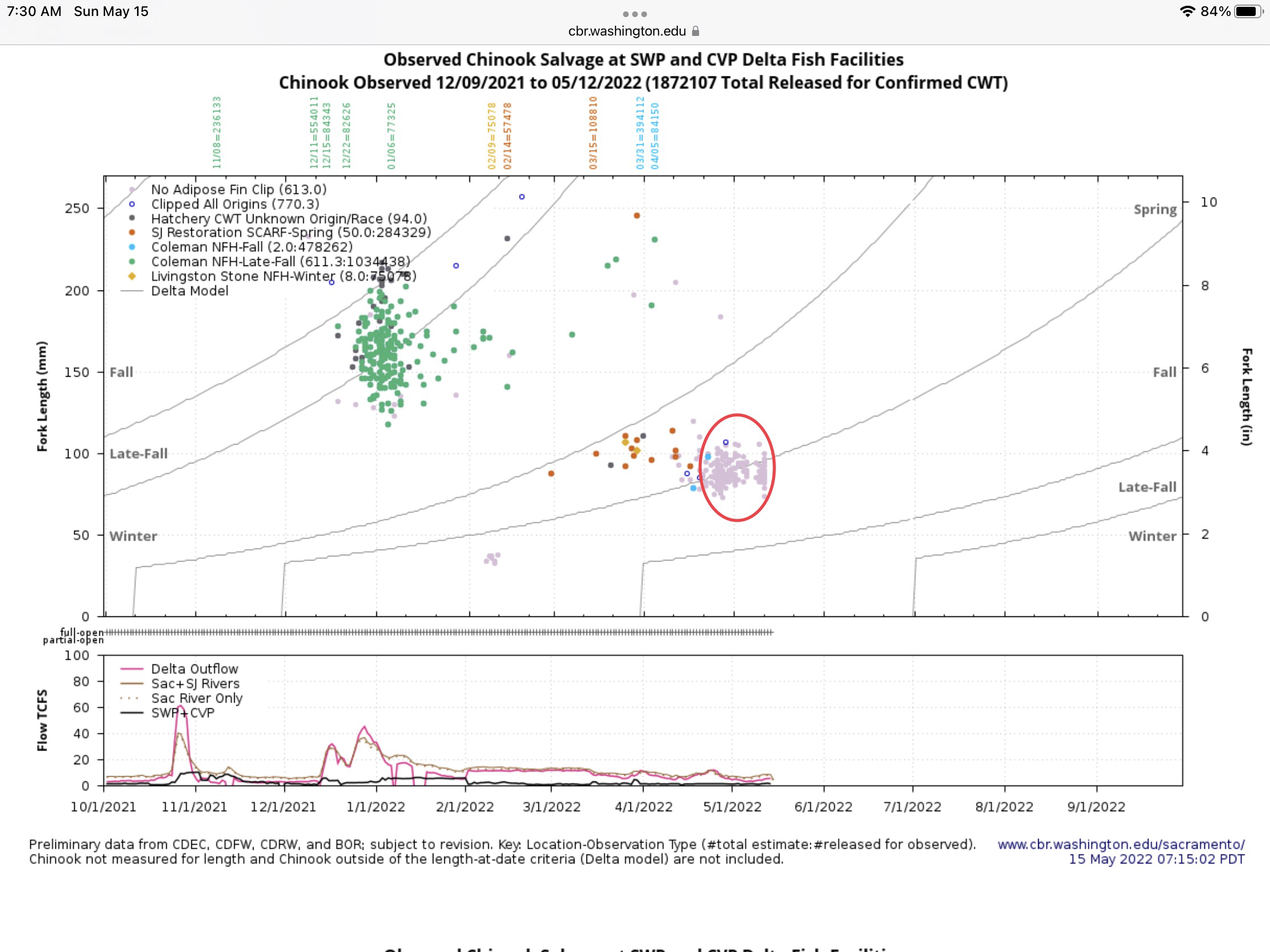

Reclamation plans to fund a six-fold increase in the production of hatchery winter-run smolts this year with staged fall-winter releases from the hatchery and Battle Creek. Such releases should timed to coincide with natural flow pulses and pulse flows from Keswick Dam.

2. Transfers of Adult Salmon

The plan includes the capture and transport of adult winter-run salmon to the headwaters of Battle Creek. Good additional measures would be to give these adult fish thiamine injections and to enhance spawning gravels in Battle Creek as soon as possible.

3. Thiamine Treatments

Stresses imposed prior to spawning (e.g., delayed spawning, low flows, warm water during migration) and holding contributes to thiamine deficiency and high mortality of yolk sac fry, both in hatcheries and wild salmon. Only hatchery salmon can be treated effectively at adult or egg stage, so efforts should be made to treat any wild adults that are handled, as well as to minimize pre-spawning stresses (e.g., erratic flows and high water temperatures).

4. Water delivery cut to 18% to Settlement Contractors

The TMP proposes to limit water deliveries to Sacramento River Settlement Contractors to 18% of their contracted amounts. The State Board should enforce this limitation. Reclamation should subordinate the timing of water releases to contractors to the needs of salmon downstream of Keswick Dam.

5. Reduced Downstream Deliveries

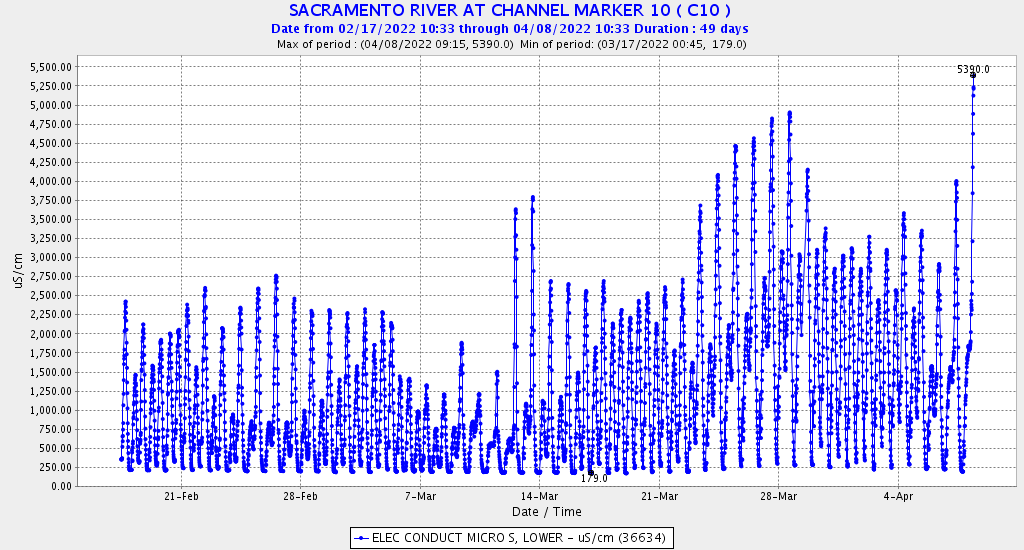

Demand on Shasta storage for Delta inflow/outflow has been reduced by relying more on other SWP/CVP and non-project reservoirs. However, lower Sacramento River and Delta inflows have reached water temperatures above 65ºF in early May, which puts additional stress on salmon that are immigrating in late spring. It is not a question of whether in May or June lower river water temperatures will exceed 68ºF – the state standard – but when.

6. System-Wide Water Management

Reclamation plans to manage system water supplies to minimize demands on Shasta’s cold-water supply. The Plan and temperature modeling relies on numerous drought actions throughout the Sacramento watershed to reduce reliance on stored water from CVP and SWP reservoirs this summer. “These drought actions have added a degree of flexibility to manage storage at Shasta, Oroville and Folsom reservoirs for meeting public health and safety needs, repelling salinity in the Delta, producing hydropower and providing additional cold water for fishery protection throughout the summer.” In 2022, Reclamation has finally cut deliveries to Sacramento River Settlement Contractors substantially below minimum amounts stated in contracts, in order to protect salmon. However, DWR has not done so for Feather River Settlement Contractors. Reclamation and DWR should be looking at system-wide delivery reductions. Reclamation should also call on New Melones for Delta salinity control as needed. See also NRDC et al. Objection to the TMP (May 6, 2022) for additional recommended system measures.

7. Real-Time Adjustments and Reporting

“Daily releases may vary from these flows to adjust for real-time operations. Significant uncertainties exist within the forecast that will require intensive real-time operations management throughout the summer to achieve the various goals and targets throughout the system.” Reporting, scrutiny, and decision making should be open processes.

8. Restoration of Salmon Upstream of Dams

Reclamation is committed to restoring endangered salmon to their historical habitat upstream of Central Valley rim dams. This program should be accelerated.

Tables 1 and 2 are copied directly from the Final TMP dated May 2, 2022.

Figure 1. Keswick Dam release water release rate and temperature, April-November 2021. Five general periods (A-E) are depicted, based on flow-temperature conditions as described in more detail in text. A. Spring high storage release rate (6-9K cfs), including extensive power bypass releases of warm surface water. B. A late-June cold water release to stimulate winter-run salmon spawning (<53ºF). C. A post-spawn higher irrigation release period with late-egg-stage sustaining water temperatures. D. Cold-water pool saving period with falling flows and higher water temperatures. E. Early fall period with loss of access to cold-water pool and reduction in storage releases.

Figure 2. April-December 2021 Sacramento River flow below Keswick Dam (river mile 300) and below Wilkins Slough (river mile 120). The difference between the two locations, plus tributary and ag return inputs, equals total irrigation deliveries via surface diversions and ground water depletions.

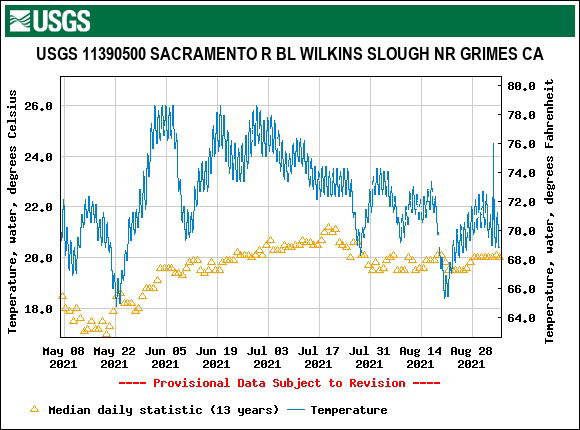

Figure 3. Water temperature in the lower Sacramento River at Wilkins Slough (river mile 120) May-August 2021, along with average for past 13 years. Note that the state’s year-round water quality standard for the lower Sacramento River is for water temperature to remain below 68ºF. Water temperatures above 65ºF are stressful to migrating juvenile and adult salmon. Water temperatures above 70ºF hinder adult salmon migration. Water temperatures above 75ºF are lethal to salmon.

Figure 4. Shasta Reservoir storage in 2022 and other selected years.

Figure 5. Shasta Reservoir water temperature profile at end of April 2022.

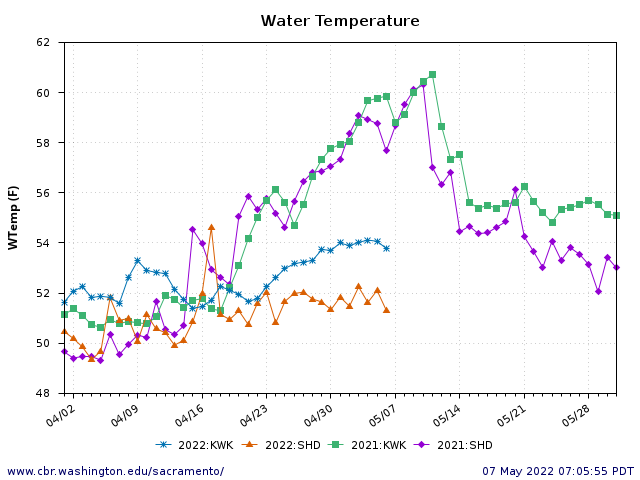

Figure 6. Water temperatures of Shasta and Keswick Dam releases in 2021 and to date in 2022.

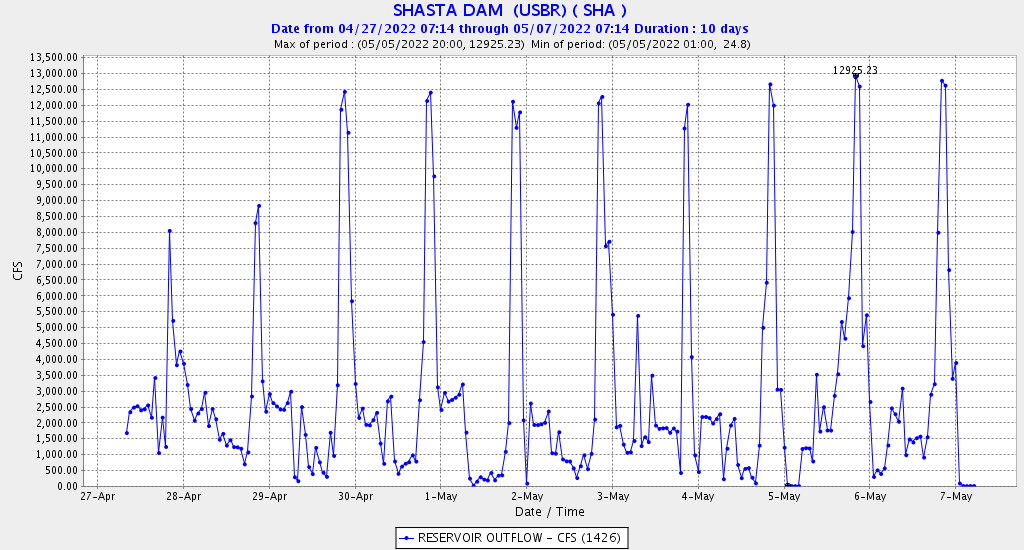

Figure 7. Hourly water temperature in Shasta Dam releases, 4/27-5/7 2022.

Figure 8. Hourly Shasta Dam flow releases 4/27-5/7 2022.