In a Maven 1/17/19 post, US Fish and Wildlife Service hatchery managers discuss problems that have developed from trucking salmon smolts from the Coleman National Fish Hatchery (Coleman NFH) to San Francisco Bay. Chief among these problems is that juvenile fish trucked from Coleman NFH stray into other Central Valley rivers as spawning adults, rather than returning to Coleman NFH. This has become a general argument for releasing Coleman NFH smolts near Redding instead of trucking or barging them to the Bay.

During the 2013-2015 drought, many Coleman NFH smolts were trucked to the Bay for release to meet the hatchery’s goals:

The management goals for the hatchery are to provide about 1% of their production or about 120,000 fish from each brood year to the ocean fishery, the freshwater sport fishery, and returns to Battle Creek for brood stock, all while trying to reduce negative impacts on naturally spawning fish.

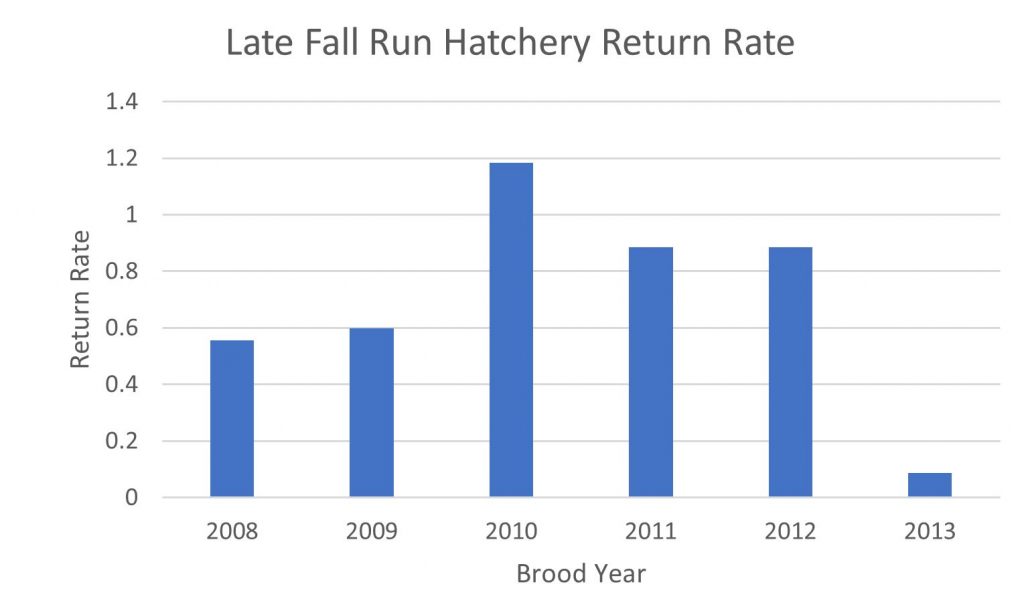

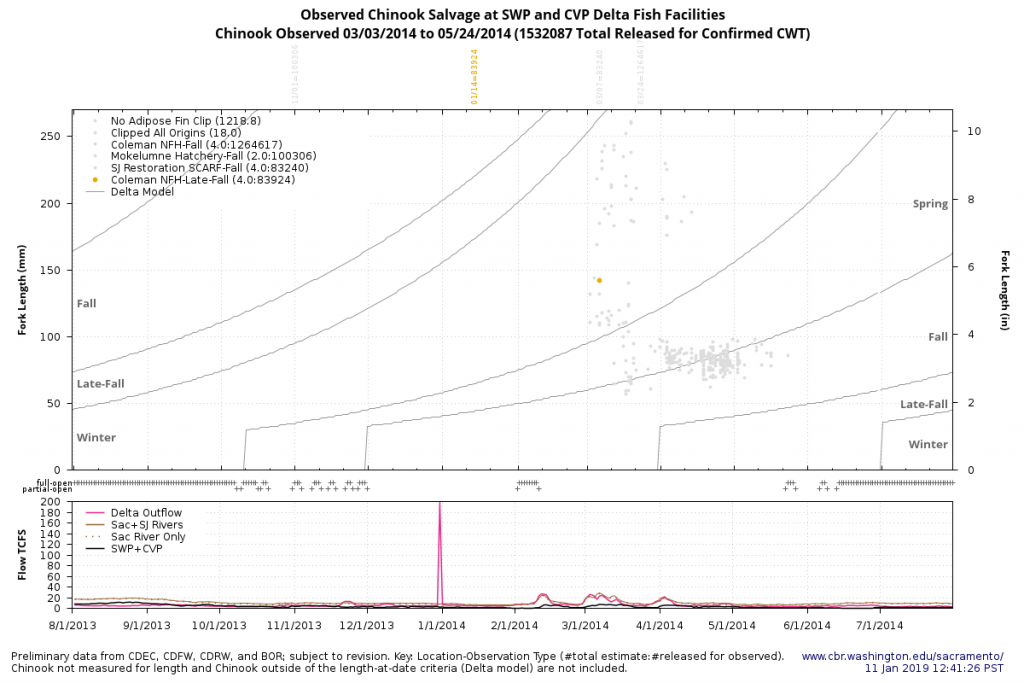

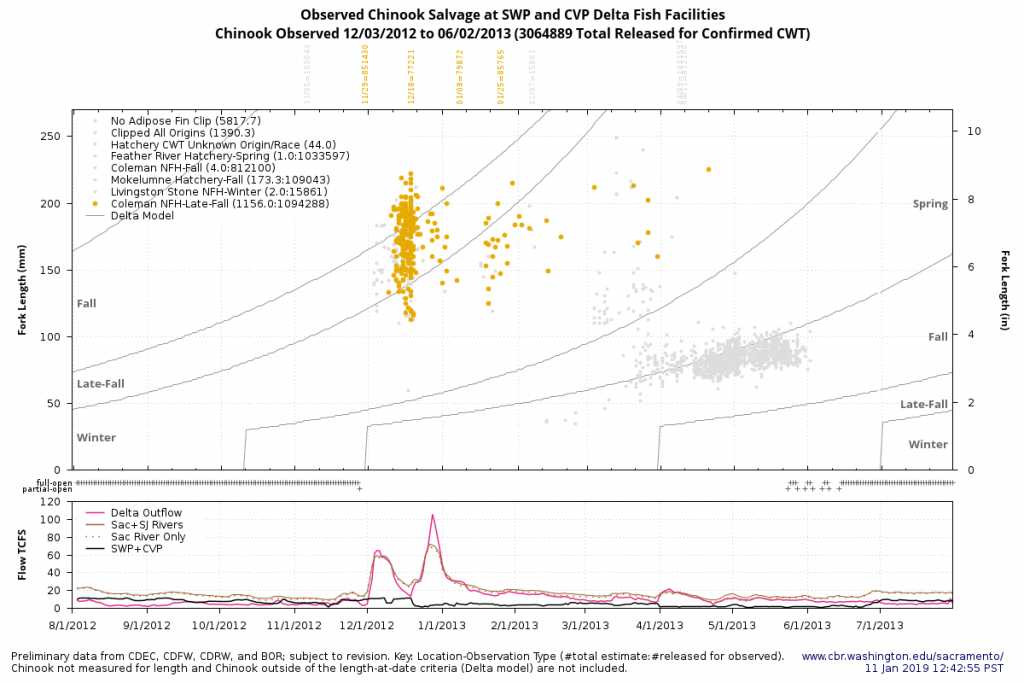

From 2013-2015, 35.5 million fall run smolts, about 12 million per year, were reared for release by the Coleman NFH. In 2013, all were released at the hatchery into Battle Creek. In 2014, 3.4 million were released at the hatchery, and the remainder were trucked to the Bay. In 2015, all 12 million were trucked to the Bay. Since 2015, all Coleman NFH fall-run smolts have been released at the hatchery.

Trucking during the drought did meet the 1% production goal, but did not provide adequate hatchery returns for broodstock and did not achieve low straying rates. The USFWS has since chosen to ignore the production goal in order to achieve the other two goals. In dry years, the 12 million smolts now provide 10,000-20,000 adults (0.1-0.2%) to fisheries instead of 100,000-200,000 (1-2%). Instead of increasing hatchery production by barging smolts or improving post-release river conditions (higher flows), the fall-run salmon production program at Coleman NFH, designed explicitly as mitigation for loss of salmon from the federal Central Valley Project, is not meeting its primary mitigation goal.

In the response to Maven’s questions on USFWS presentation at the Bay-Delta Science Conference, the USFWS managers offered the following responses:

Is Straying Bad?

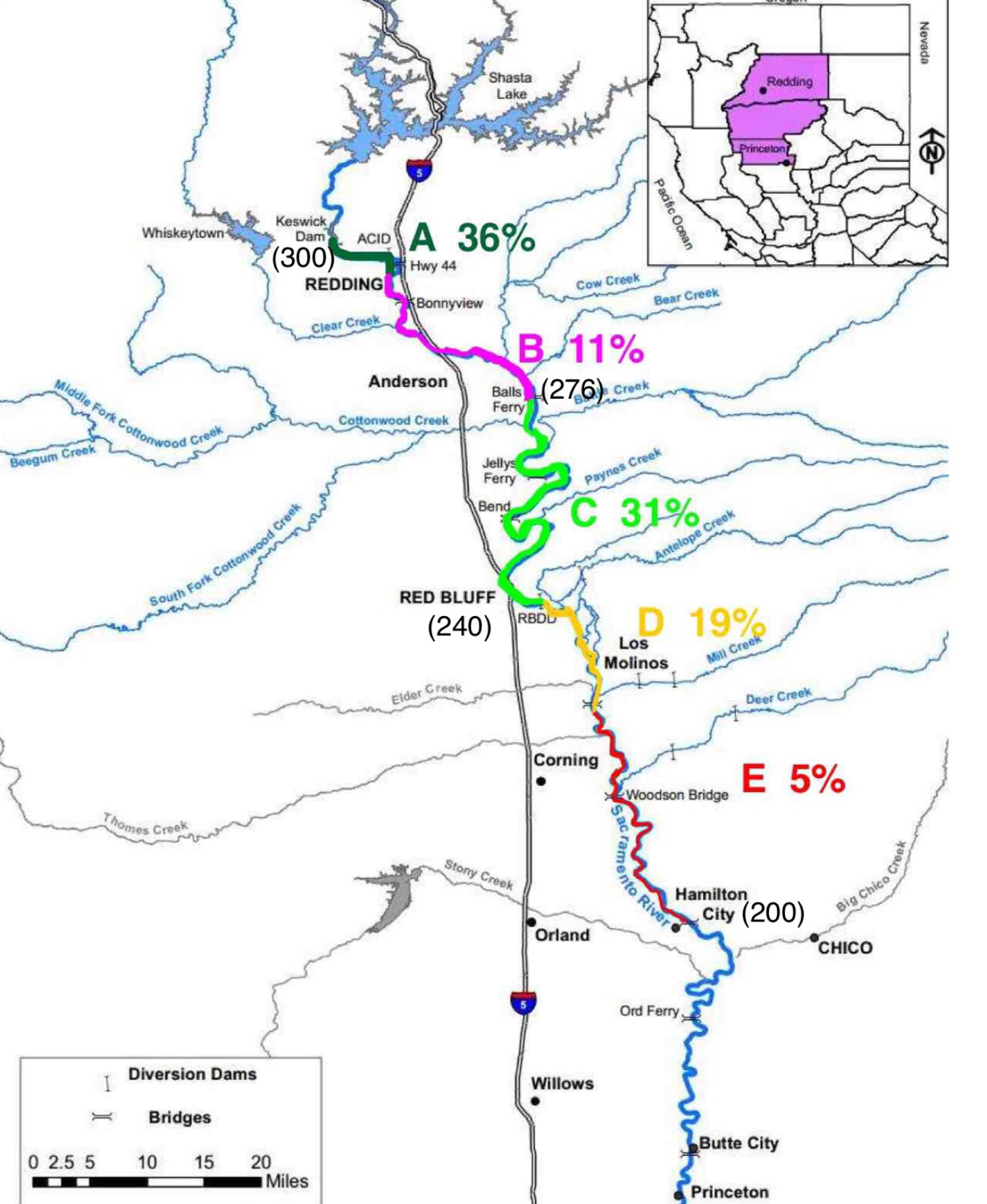

- This occurs because fish that do not naturally emigrate through the river system lose the opportunity to imprint properly and may be unable to locate their natal area when they are ready to spawn. Response: High stray rates are unique to the federal Battle Creek Coleman NFH, partially because many of their returning adults spawn in the upper Sacramento River (as intended) and do not move into Battle Creek, and are thus considered strays. Regardless of imprinting influence, returning adults to the Sacramento River are confronted with poor flows and high water temperatures above the mouth of the Feather-Yuba-Butte Creek, Mokelumne, and American rivers, so they choose those rivers out of necessity. This problem does not occur at the Feather, American, and Mokelumne state hatcheries. These other hatcheries have also transported stray, earlier-returning Battle Creek adults (or fertilized eggs) to the Coleman Hatchery to help Coleman offset its egg shortages.

- Hatchery fish that stray into natural spawning areas can detrimentally affect natural fish populations through genetic, ecological, and behavioral mechanisms…. Increased straying by hatchery fish may reduce genetic diversity within and among salmon populations. Response: While this is generally true for pristine natural salmon watersheds, this concern was long ago lost in the Central Valley after a century of disturbance and hatchery interference. Eggs have been shared, even from out of state, and even from different runs (hatcheries and dams have forced mixing of spring-run and fall-run spawners). Hatchery strays continue to dominate runs in non-hatchery rivers; without the strays, there would be few if any salmon in these rivers. Straying is also a natural process needed to retain population fitness, resilience, and genetic diversity.

- Likely due to the prevalence of off-site release practices at Central Valley hatcheries, Central Valley fall Chinook Salmon have lost locally adapted genes and become one large, genetically homogeneous population (see Johnson et al 2012). Response: Adapted genes were lost decades ago before off-site releases. Johnson et al were describing how hatchery dominance covers up underlying problems in wild populations, not necessarily how it causes the underlying problems. This is a real concern in the Central Valley where only 25% of the fall run hatchery smolts are marked. The true wild components of individual river runs need protection. For some rivers, natural spawning areas can be reserved for true wild spawners (e.g., Battle Creek, Yuba River, Mokelumne, Calaveras, Butte Creek, etc.). Wild spawners can also be relocated above rim dams. Conservation hatcheries can use “wild” spawners.

- Furthermore, salmon that are spawned and reared in fish hatcheries may become quickly adapted for characteristics that favor their survival and reproductive success in the hatchery environment while, at the same time, diminishing their ability to survive and reproduce in the natural environment. Response: while potentially (and historically) true, modern hatchery programs minimize or should minimize, if not reverse, these tendencies.

- Stray hatchery fish may also compete with natural fish populations for limited resources, including competition for preferred spawning areas by adults and competition for food resources and habitat by juvenile fish. Response: Again, while generally and historically true, hatchery adult returns now take the place of wild adults in increasingly depressed amounts of spawning habitat in Central Valley rivers. Also, it is generally known that in many cases wild adults out-compete hatchery adults for habitat. Also, in most Central Valley rivers, hatchery fall-run adults can be effectively excluded from primary spawning areas. Hatchery smolts can readily be excluded from natural rearing areas by controlling timing and location of releases. In arguing against barging or trucking, USFWS managers are in essence arguing to continue releasing their hatchery smolts into prime natural rearing areas.

- When hatchery fall Chinook Salmon from Coleman NFH stray at high rates, the freshwater fishery may be redistributed to other parts of the Central Valley and sport fishing in the upper Sacramento River fishery is negatively impacted. Response: Low flows and high water temperatures are the biggest contributor to poor upper Sacramento River salmon fishing. Also, Coleman hatchery adults that spawn in the upper Sacramento River or that are caught by sport fisherman in the Sacramento River upstream of Battle Creek are considered strays, even though they are produced to mitigate for Shasta Dam.

- High stray rates of trucked hatchery fish may impact the ability of Coleman NFH to meet its annual fish production targets. For example, in 2017 (which corresponded to age-3 adult returns of fish that were 100% trucked), less than 350 adult salmon returned to the hatchery. At a minimum, Coleman NFH needs to spawn 2,600 pairs of adult salmon to meet the production target of 12 million juveniles. As a result, Coleman NFH released less than 6 million juveniles in the spring of 2018, which will result in fewer fish available to achieve our management goals in future years. Response: Then why not release a portion of the smolts in the Bay as for brood year 2013 (2014 releases)? Other potential measures to increase egg take outlined by the authors can also be enhanced.

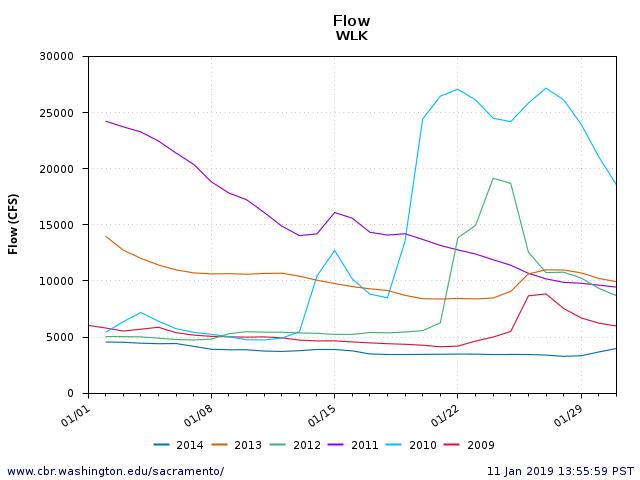

Need for Trucking

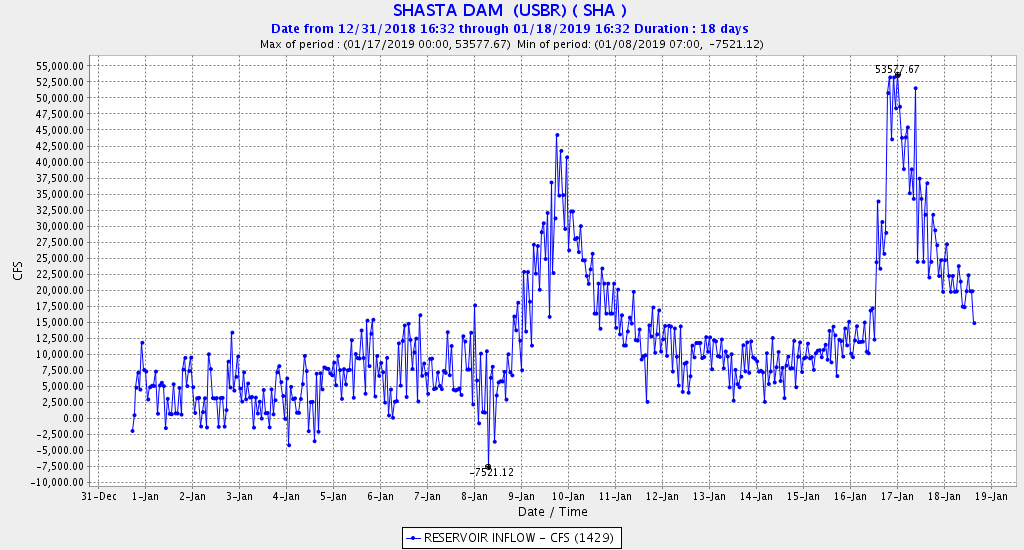

- California’s drought had some negative impacts for Coleman National Fish Hatchery….The one percent contribution goal to the fisheries and returns to Battle Creek was not able to be achieved under the drought conditions. Response: The drought was not to blame. Reclamation’s water right permits require measures to protect salmon, even during droughts. During the 2013-2015 drought, Reclamation delivered too much water to Sacramento River settlement contractors. This left Reclamation too little water to meet the conditions in its water rights permits that are designed to protect salmon. Water management during droughts is the problem.

- Despite our extra efforts to collect additional eggs, we only met about half of our production target. We’ve undertaken a study to assess fish survival under different release strategies. This information will hopefully allow for adaptive management, based on changing environmental conditions and may give us some flexibility to release fish onsite to meet our multiple management goals in the future. Response: If Reclamation provides environmental flows from Shasta, and if USFWS times releases of hatchery juveniles at Coleman NFH to water conditions, then Battle Creek releases may produce more adult salmon. Some amount of trucking may be necessary to meet overall mitigation goals.

Conclusion

Hatchery program managers should not give up on trucking and on reducing high stray rates. They should consider barging juvenile salmon to better imprint smolts and improve smolt survival. Federal water managers also need to improve lower Sacramento River conditions for returning adults, in order to reduce straying. Water contractors and state/federal purveyors must also collectively limit their water diversions to meet water right permit conditions and water quality standards that are designed to protect fish. Egg taking should be increased if hatchery releases are to continue, in order to meet mitigation goals. These measures will all help hatchery managers meet their adult production goals and mitigation commitments. Trucking, a standard practice at state hatcheries in all year types, may be necessary, especially in periods of drought, to meet mitigation goals.