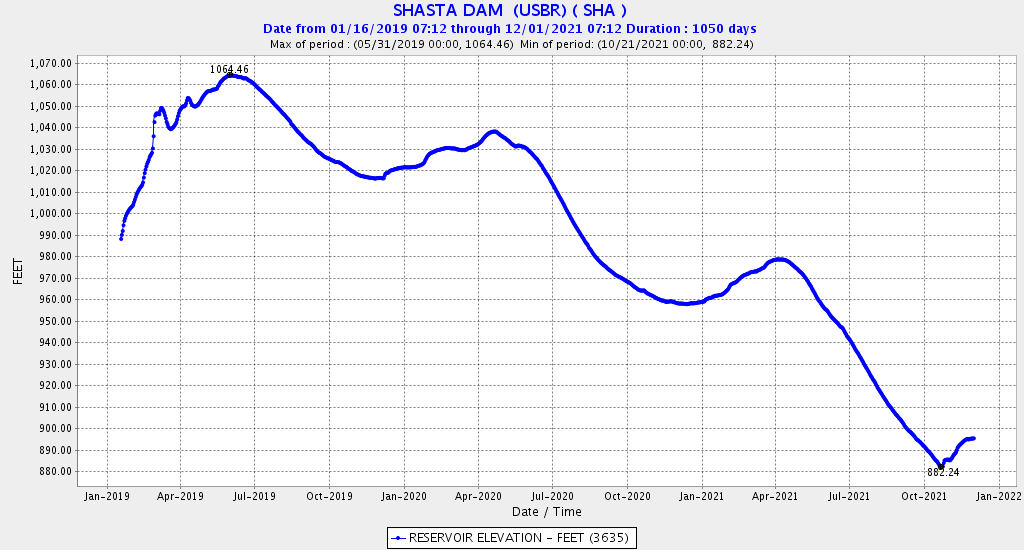

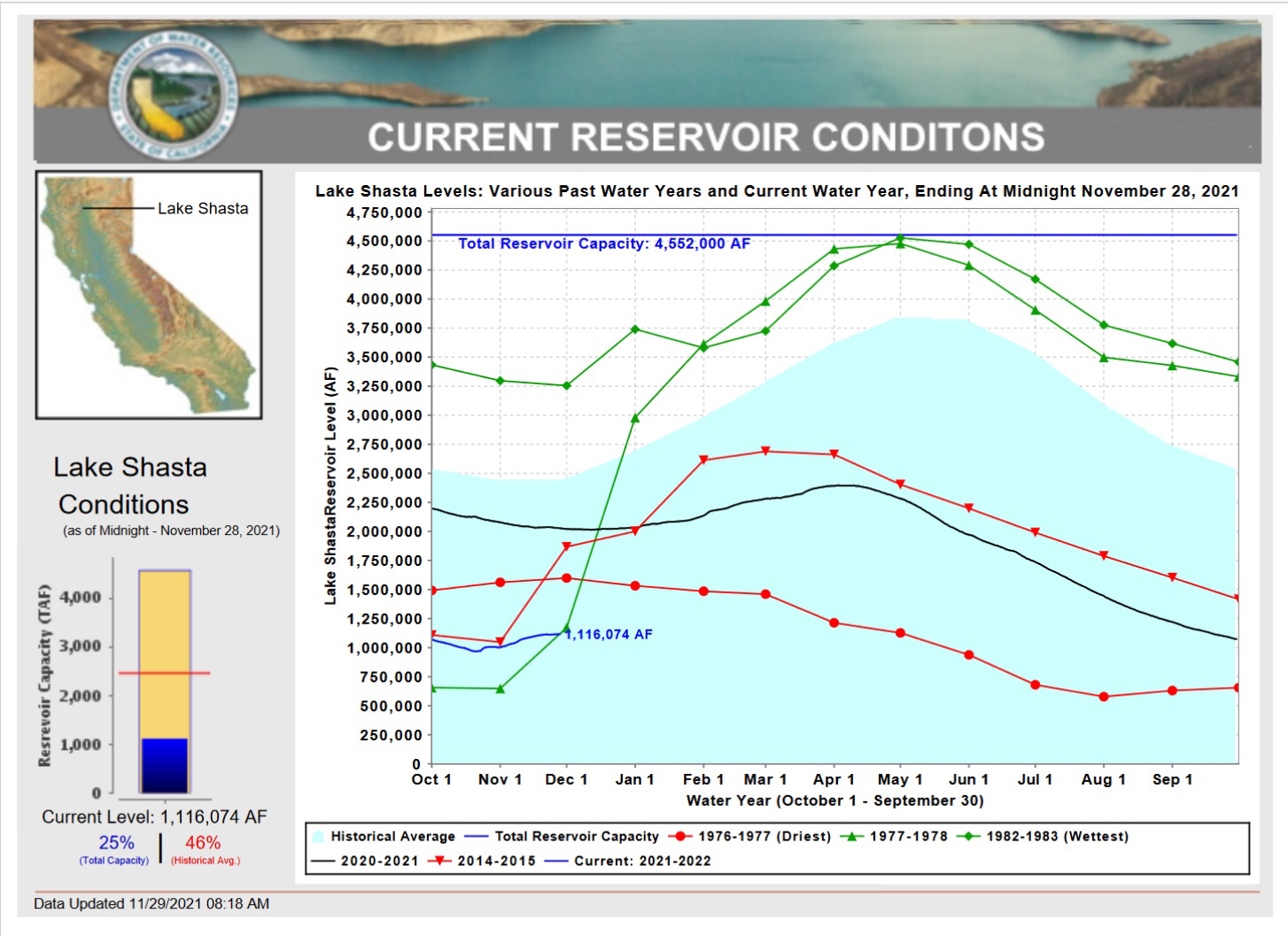

Fall-run salmon spawn in the fall in the 20-40 miles of the Sacramento River downstream of Keswick Dam near Redding. Numbers of in-river fall-run spawners have declined severely over the past several decades (Figure 1). Declines were worst three years after drought periods (2007-2009, 2013-2015), due to poor egg and fry survival during droughts. A February 2021 post discussed the role of redd dewatering and fry stranding from severe drops in flow and water level (stage) as major drought-related factors in the escapement declines. A 2018 post listed a broader range of factors, including high water temperatures during droughts in addition to stranding.

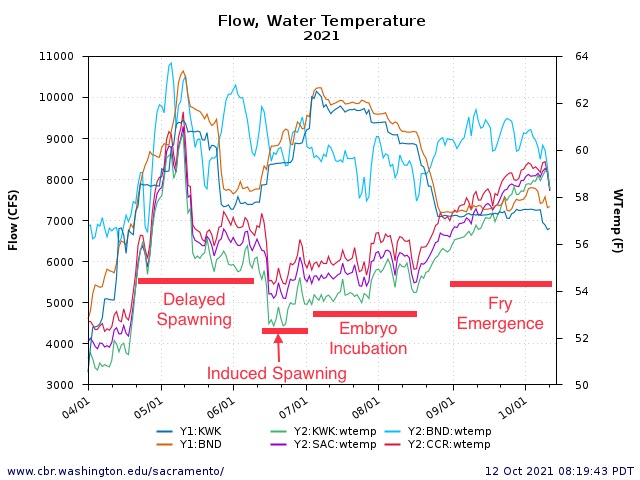

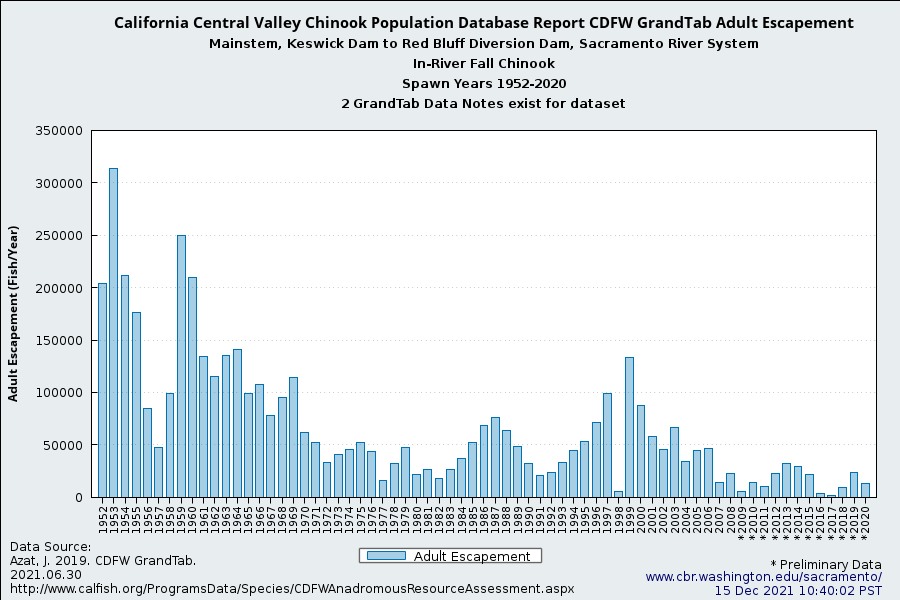

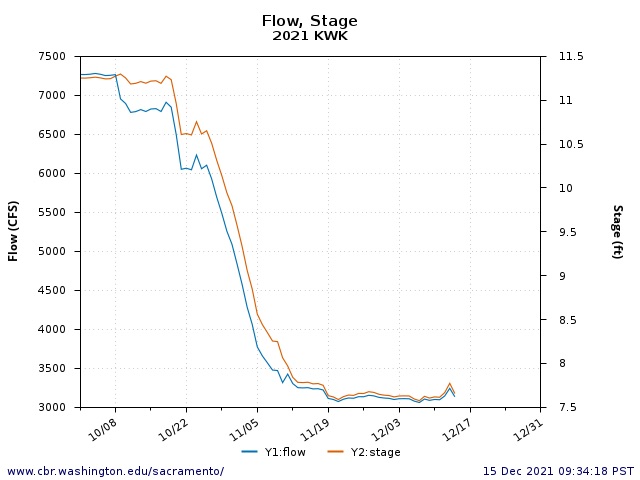

Stranding was once again a major factor in fall 2021 as water levels near Redding dropped 4 feet from October to November (Figure 2). Further downstream in the lower spawning reach, salmon have also had to contend with high flows as well (Figure 3). High flows (1) encourage salmon to spawn in margin habitat that later dewater, and (2) cause scouring of redds spawned earlier at lower water levels.

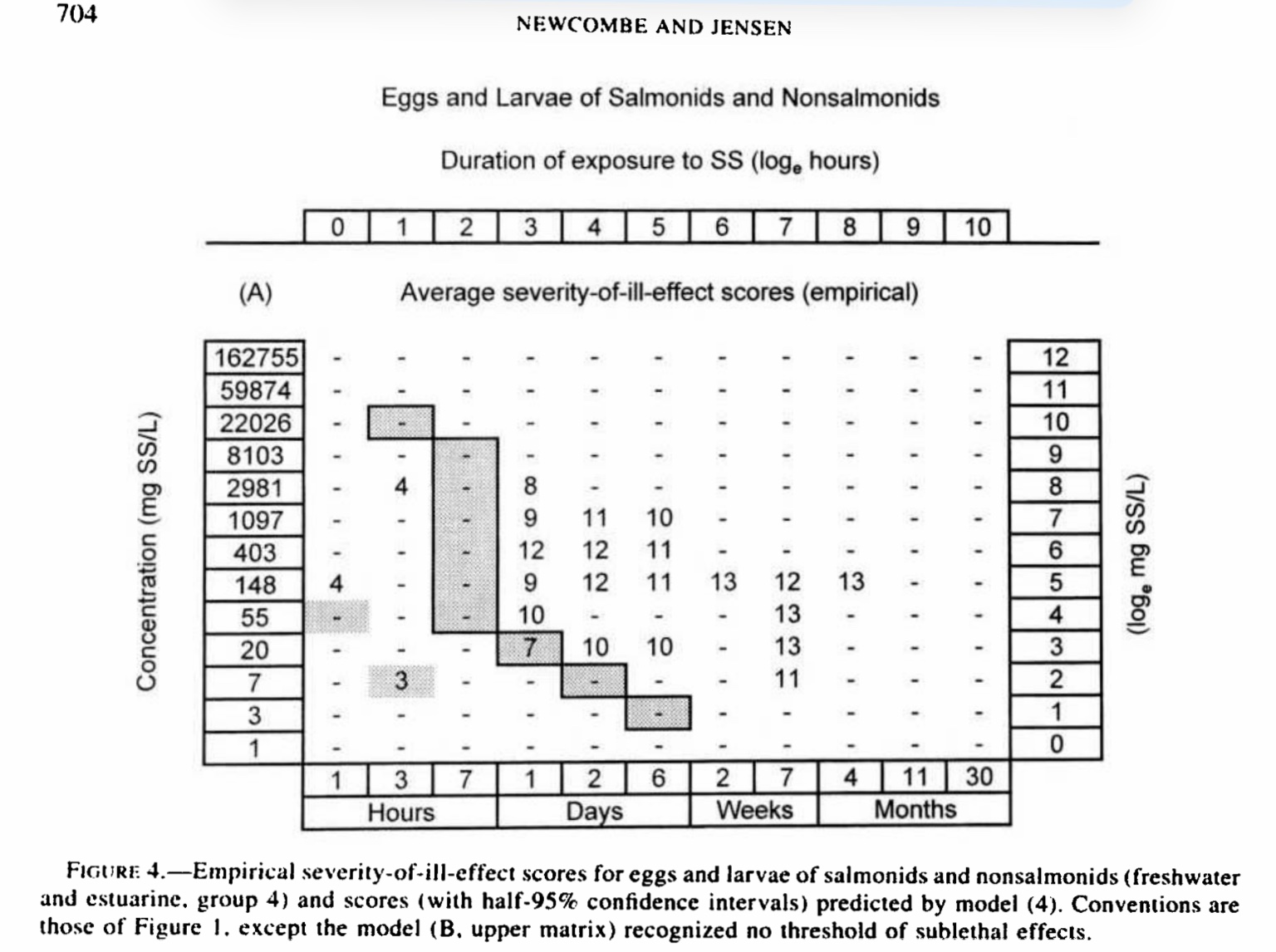

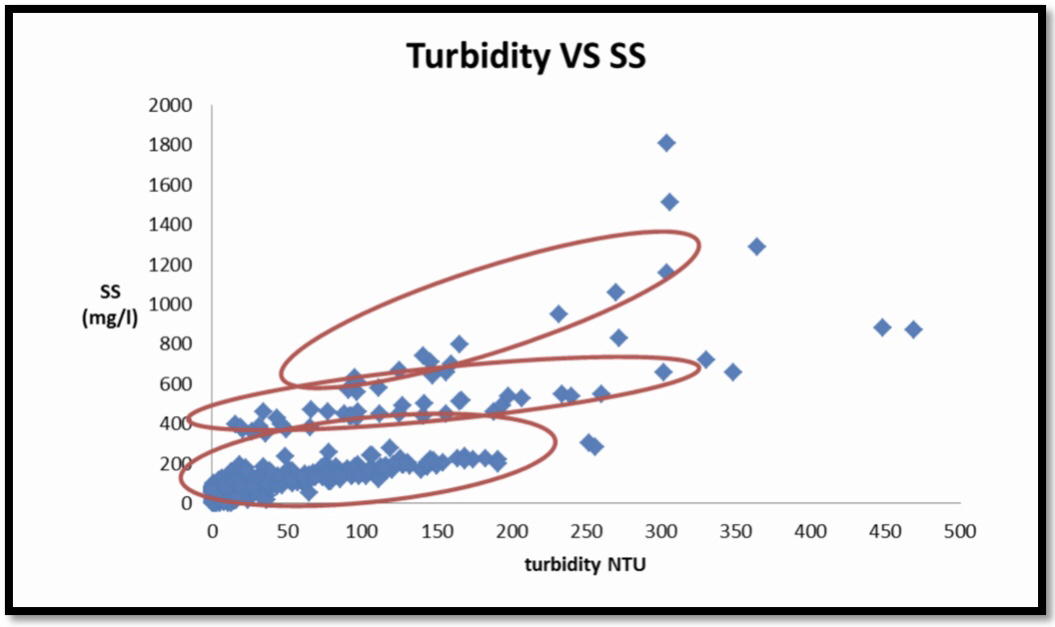

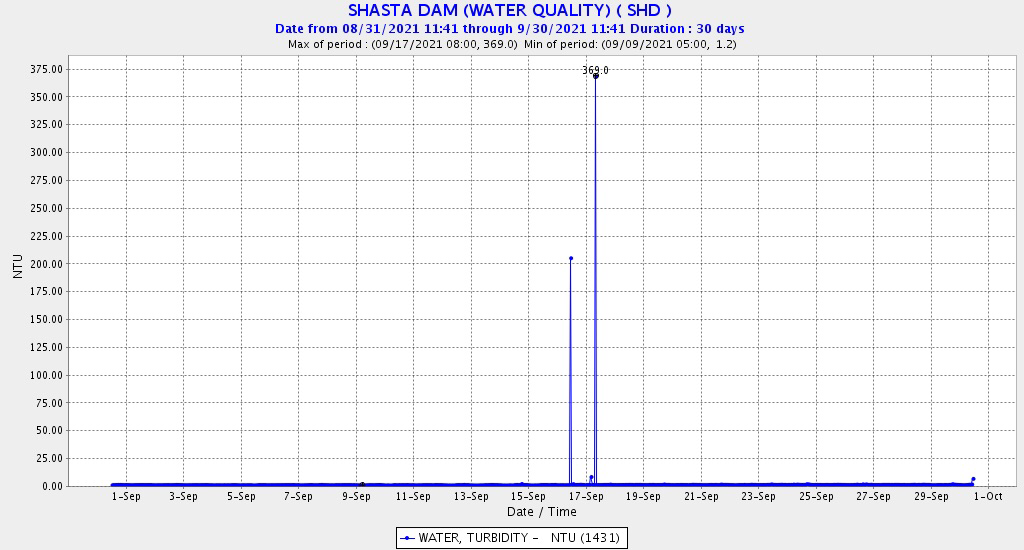

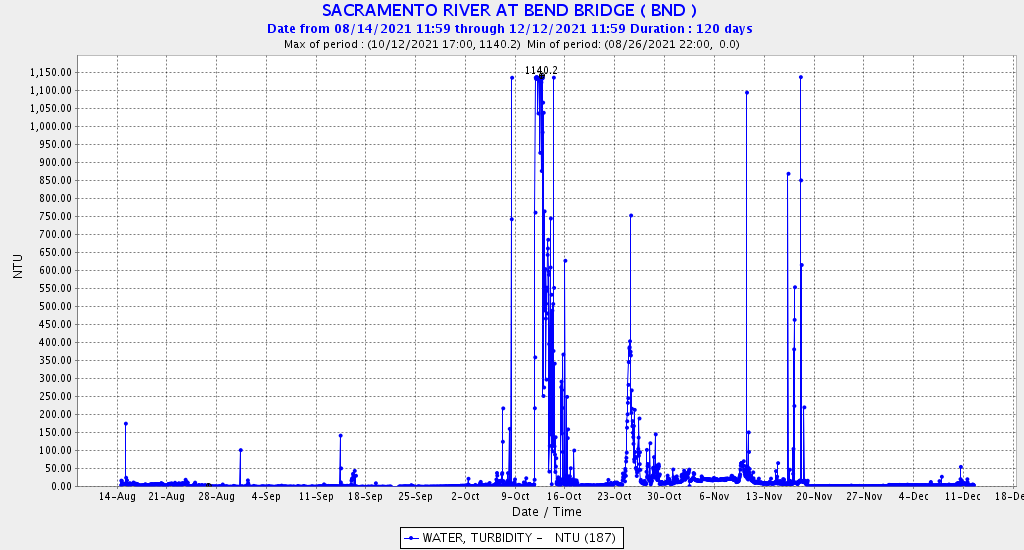

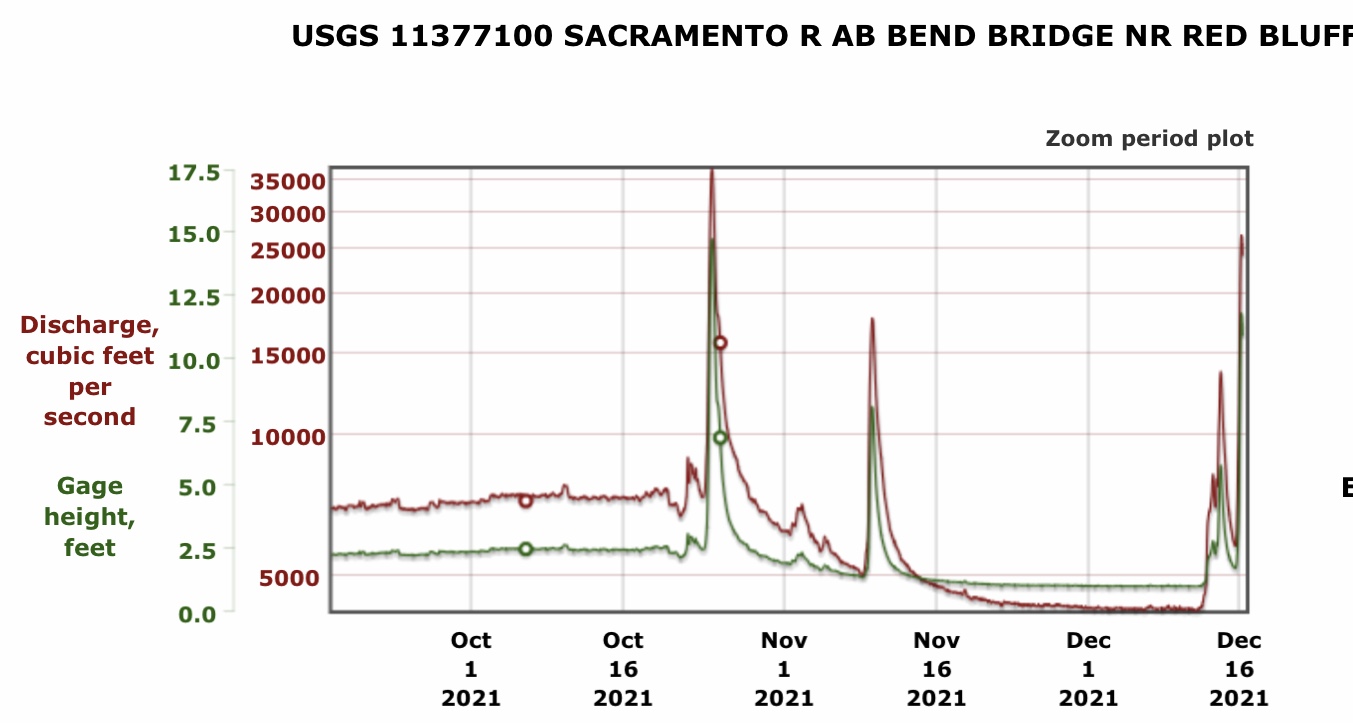

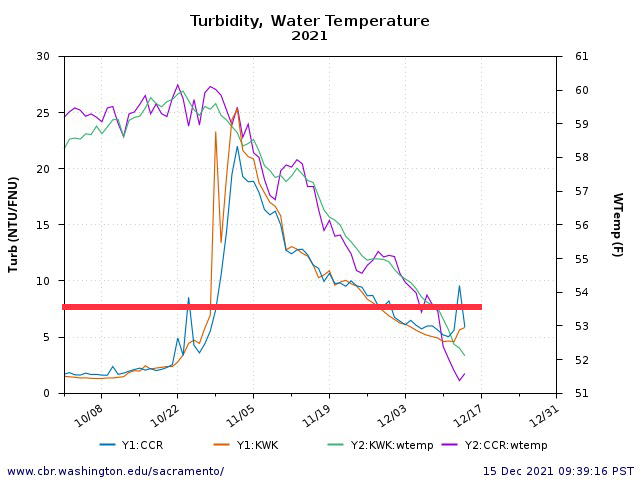

In fall of drought year 2021, an additional severe-mortality factor has become apparent. Turbidity/suspended sediment levels in the spawning reach (Figure 4) were at or above lethal levels for salmon eggs and embryo (see December 23, 2021 post) for most of November, a peak spawning period. The late-October record storm and subsequent further rain and runoff have elevated inflows to Shasta Reservoir. As these higher flows have entered the reservoir, they have eroded vast areas of sediment exposed in the drought-depleted reservoir.1 The suspended sediment has carried through the reservoir into the spawning reach below Keswick Dam.

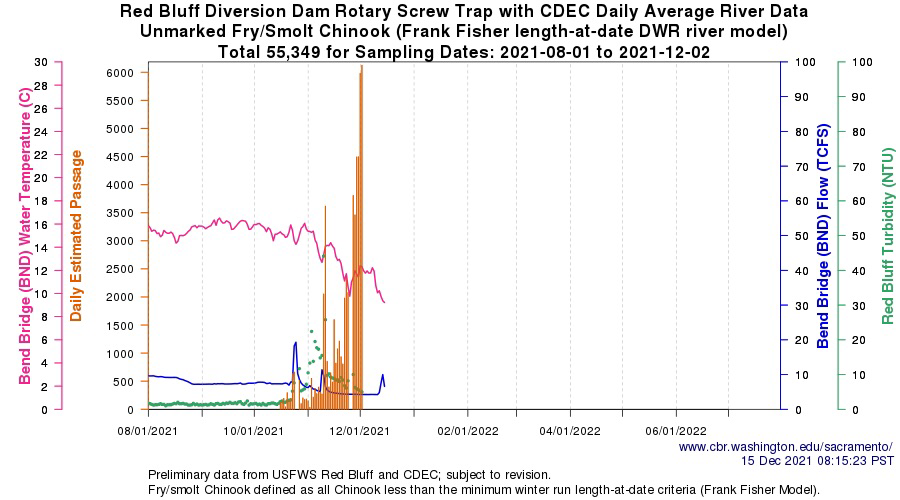

Of positive note, the higher flows (Figure 3) and associated turbidity have likely helped salmon fry that spawned earlier in tributaries like Battle Creek and Clear Creek move downstream in the Sacramento River toward the Delta and Bay.

In summary, fall-run salmon spawning in the most upstream reach of the lower Sacramento River near Redding have faced extreme habitat conditions in 2021. These conditions began with high October water temperatures from a depleted cold-water-pool in Shasta Reservoir. Next came a four-foot drop in water level due to sharply reduced Shasta Reservoir releases. Added to these traumas were egg-smothering levels of suspended sediments from Shasta Reservoir caused by erosion of drought-exposed, decades-old reservoir sediment during a record-level late October storm and subsequent runoff events.

Figure 1. In-river fall-run Chinook adult escapement to the upper Sacramento River 1952-2020.

Figure 2. Streamflow (cfs) and water surface elevation (stage) in the Sacramento River immediately below Keswick Dam October 1 – December 15, 2021.

Figure 3. Streamflow (cfs) and water surface elevation (stage) 50 miles below Keswick Dam October 1 – December 15, 2021. High flows were from tributary inflows below Redding (Cow Creek, Battle Creek, Clear Creek, and others).

Figure 4. Water temperatures and turbidities below Keswick Dam (RM 300) and above the mouth of Clear Creek (RM 290) October 1 – December 15, 2021. Red line depicts literature-based, severe-mortality turbidity level for eggs and embryo salmon for a one-day exposure.

Figure 5. Spring and fall run salmon fry catch at Red Bluff (RM 240) screw traps August – November, 2021. Also shown are nearby Bend Bridge water temperature and flow, and Red Bluff turbidity.

- See photos at https://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/?p=4001. ↩