On Wednesday, February 10, 2016, the Water, Power and Oceans Subcommittee held a one-panel oversight hearing on “The Costly Impacts of Predation and Conflicting Federal Statutes on Native and Endangered Fish Species.” FISHBIO President Doug Demko was invited to provide testimony on the issue in reference to California’s Central Valley.

FishBio photo

FishBio’s testimony begins: “California resource agencies sink tens of millions of dollars every year into a failing effort to protect native and endangered fish species, while also bolstering introduced top-level predators that are decimating the very fish they are required to maintain.”

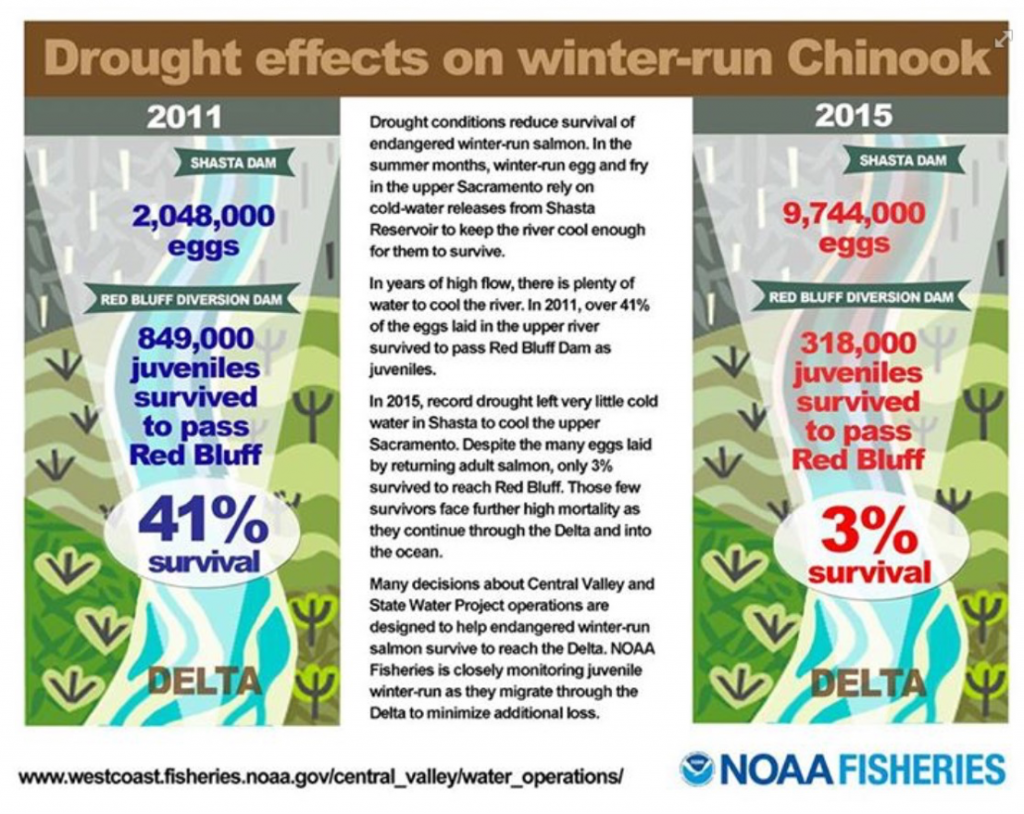

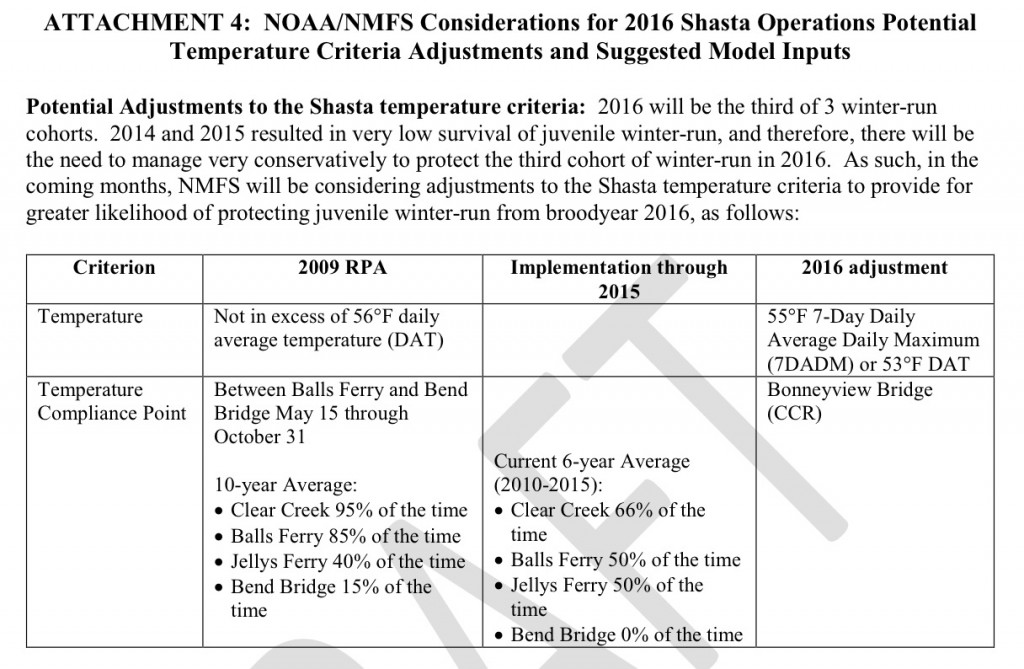

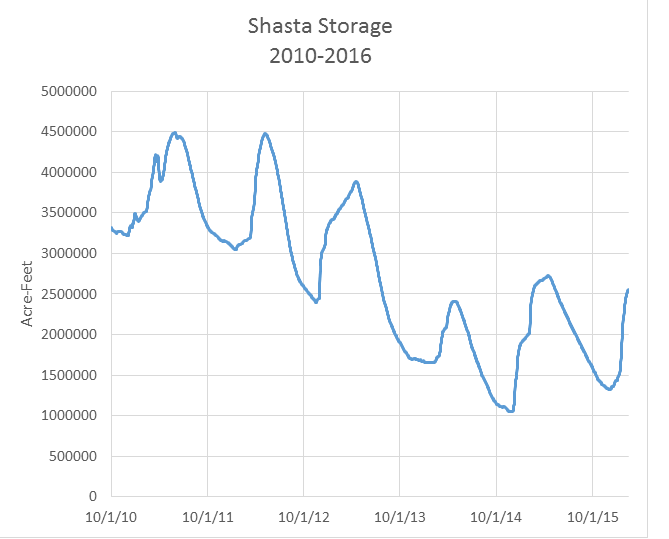

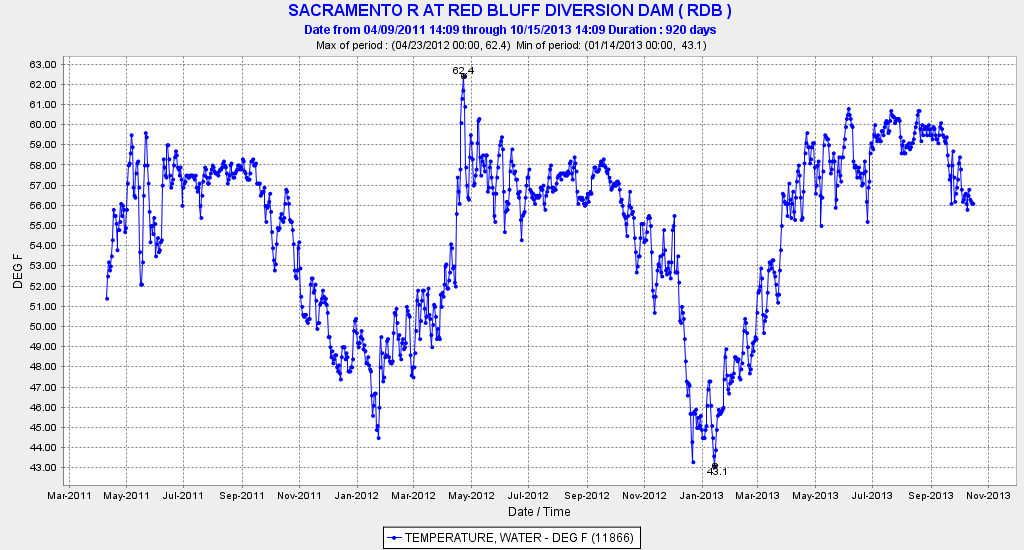

- Failure to protect native and endangered fish species in the Central Valley has far more to do with water management within the federal Central Valley Project and State Water Project and lack of protections from water quality standards and biological opinions, especially during four multi-year droughts beginning in the late-1970’s. Over a billion dollars have been spent by federal and state agencies on fish recovery, with strongly positive results between droughts.

-

In no way have the recovery efforts bolstered introduced top-level predators such as the striped bass. As noted in the testimony, stocking of striped bass ceased nearly two decades ago. Striped bass production had declined dramatically over the past three decades along with the native fish. Summer water quality standards that once protected striped bass were removed twenty years ago.

-

The increases in stocking of hatchery salmon smolts to over 30 million annually in the Central Valley have encouraged and sustained the remaining striped bass, which now focus more on young salmon. Adult striped bass now concentrate in spring below all the Central Valley salmon hatcheries and dams. Remnants of the once prolific striped bass population await the fat hatchery smolts in all 300 miles to the Golden Gate. A shift in prey and location of prey has forced more Striped Bass into the rivers and tributaries for prey.

-

Photo: yearling hatchery steelhead smolt fed on wild salmon fry in American River. (Photo by author)

The stocking of millions of large yearling salmon and steelhead smolts also contributes directly to predation on wild salmon and steelhead fry. (see photo at right)

- Research has shown that habitat changes have had more to do with increased predator populations like largemouth bass in the Delta. Controlling habitat change is the proven way to limit predators, rather than direct control of predators, which does not work (logistically impossible and very costly and inefficient).

“However, only recently has the existing body of science on predation been recognized among fisheries managers as a major source of juvenile salmon mortality.” This statement is simply not true. Hatchery salmon smolts have been trucked to the Bay for three decades to avoid the hundreds of miles of predator gauntlet. Predation studies at specific locations such as the Red Bluff Diversion Dam have long indicated predation problems. The dam was removed because it was a recognized predator “hot spot”.

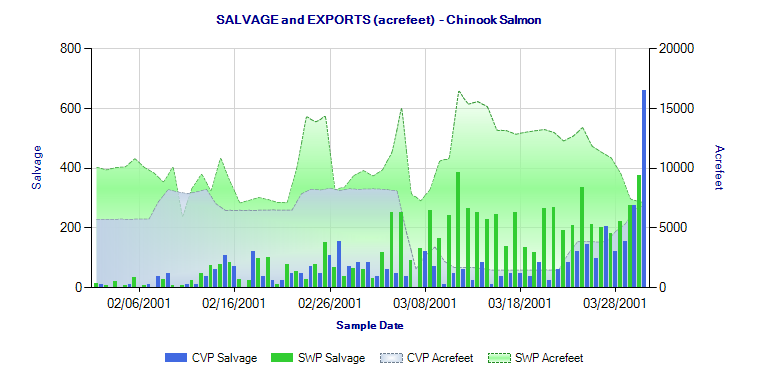

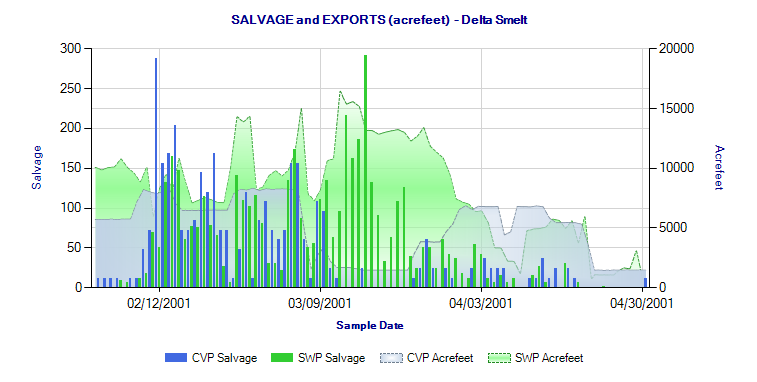

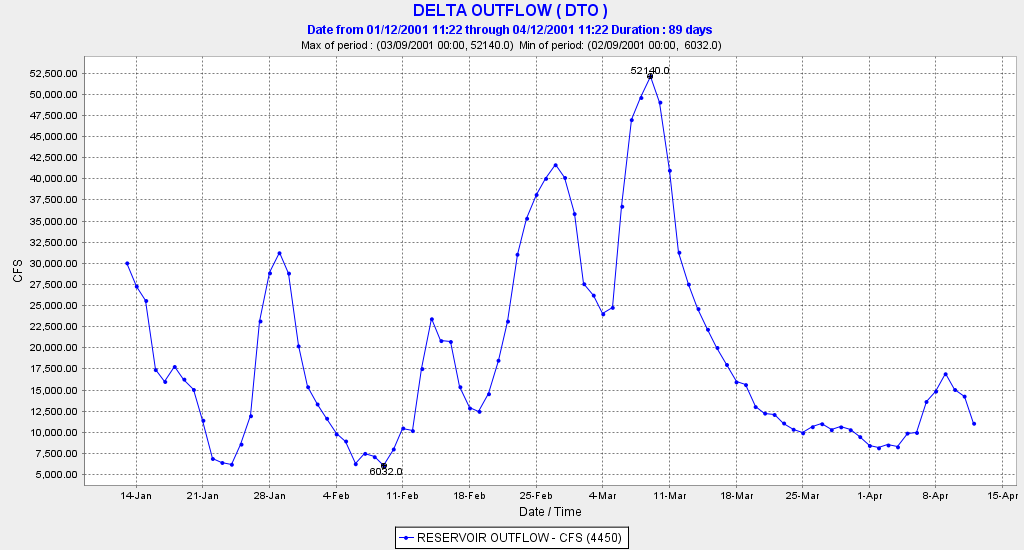

There is no doubt that predation by non-native fish like Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass is a major factor in Chinook Salmon and Steelhead mortality in the Central Valley. However singling them out as the primary cause of native fish declines misses the key factor: water management. Salmon, smelt, and bass got along well until the State Water Project came on line in the 1970s and increased Delta exports from 2 million to 6 million acre-feet per year. There is no doubt that droughts and climate change have added to or sped up changes; however the underlying problem remains water diversions.

“It has now become clear that predation may significantly limit the success of salmon recovery efforts (NMFS 2009b; Dauble et al., 2010).” While this statement may be true under existing conditions where salmon production is limited by water management and habitat degradation (with predation exacerbated by these factors), the solution should be a broader range of risk factor management, not just a focus on predation. For example, spring reservoir releases can reduce predation risk by speeding emigration, increasing turbidity, and reducing water temperature.

“The survival estimate of 7% in 2012 was much lower than the 40-60% previously estimated by mark-recapture studies conducted by CDFW.” In drought years like 2012, reservoirs capture and retain nearly all winter-spring flows. No doubt this creates better conditions for Striped Bass (and resident Rainbow Trout and Pikeminnow) predation on young salmon that are programmed to emigrate when Mother Nature provides appropriate freshets. So is the problem predation or lack of natural flows? (This problem could be partly mitigated through a more comprehensive approach in the worst case drought years by capturing young salmon in migrants traps and transporting them to the Bay, thus avoiding the predators in the river (and Delta). In such dry years adult Striped Bass could also be effectively captured in upstream migrant traps and transported to the Bay where other types of prey are far more abundant.)

“[N]o changes in sportfishing regulations, and, to date, no meaningful actions of any kind have been taken to accept or address the problem.” Changing sport fishing regulations would be a drop in the bucket and alienate most sport fishermen. Why doesn’t CDFW take the hundreds of thousands of young striped bass salvaged each summer at the Delta export pumps (and returned to the west Delta) and stock them in a southern California reservoir? Because that would cripple the Bay-Delta striper fishery – an angler’s Catch-22. Why doesn’t CDFW take the catch from hundreds of bass tournaments each year in the Delta somewhere other than nice spots in the Delta? Because that would cripple the world-renowned bass fishery – another Catch-22. FishBio describes the bounty fishery on Columbia River predators that are less desired as gamefish. It is altogether different to put a bounty on Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass.

FishBio noted that harvest restrictions on non-native sport fish have recently been removed on the Columbia River to protect native salmonids. “A similar policy change in California, coupled with focused removal and suppression efforts, could lead to improved survival conditions for native species as has been demonstrated on the Columbia River.” Columbia River salmonid fisheries are far more valuable and popular than bass and walleye fisheries. Furthermore, there is little else managers can do on the Columbia to benefit salmon. Water diversions in the Columbia are far less of a problem, and managers on the Columbia have already severely limited hydropower production to provide spring spills for salmon. These actions have brought record or near record salmon and steelhead runs.

In conclusion, Striped Bass and Largemouth Bass are two of the top sportfish in the Central Valley. Destroying their populations and sport fisheries, and associated socio-economic benefits, without addressing water management, the real culprit, will not solve or defuse the problem.

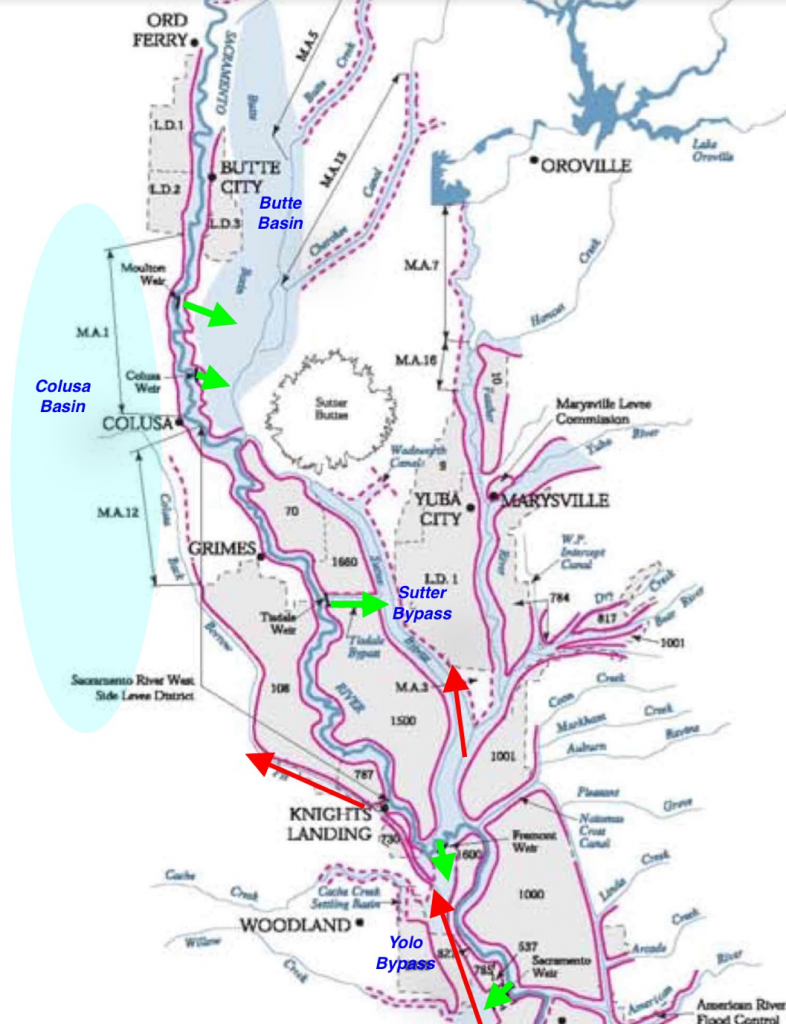

It is one of those wet springs when the Sacramento River has spilled over the Fremont Weir at the upstream (north) entrance to the Yolo Bypass near Verona. In a January post I summarized the need to fix salmon and sturgeon passage at the weir. In early April 2011 adult sturgeon and salmon were rescued at Tisdale and Fremont weirs1 under nearly the same circumstances that have developed since mid-March this year. In the coming weeks, many adult sturgeon and Winter Run salmon attracted by the high Bypass flows will again show up and become stranded at the Fremont Weir as the weir ceases to overflow. River levels are expected to drop as much as eight feet in the coming week. As the Bypass slowly drains in the coming days more and more salmon and sturgeon will migrate up the Bypass via Cache Slough near Rio Vista. Many will become stranded in the upper Bypass as far up as the Fremont Weir concrete apron, where rescues occurred in the past.

It is one of those wet springs when the Sacramento River has spilled over the Fremont Weir at the upstream (north) entrance to the Yolo Bypass near Verona. In a January post I summarized the need to fix salmon and sturgeon passage at the weir. In early April 2011 adult sturgeon and salmon were rescued at Tisdale and Fremont weirs1 under nearly the same circumstances that have developed since mid-March this year. In the coming weeks, many adult sturgeon and Winter Run salmon attracted by the high Bypass flows will again show up and become stranded at the Fremont Weir as the weir ceases to overflow. River levels are expected to drop as much as eight feet in the coming week. As the Bypass slowly drains in the coming days more and more salmon and sturgeon will migrate up the Bypass via Cache Slough near Rio Vista. Many will become stranded in the upper Bypass as far up as the Fremont Weir concrete apron, where rescues occurred in the past. Others will make their way to the west side of the upper Bypass to outlet of the Knights Landing Ridge Cut (KLRC), and migrate up into the Colusa Basin via the Colusa Basin Drain where they will be lost. In spring 2013, many Winter Run salmon were found stranded in the Colusa Basin under similar circumstances. The peak migration of Winter Run and sturgeon is in March and April. So I expect many salmon have or will be headed up the Ridge Cut, which is flowing 500-600 cfs.2 The CDFW trap is removed from the Ridge Cut outlet at such high flows.

Others will make their way to the west side of the upper Bypass to outlet of the Knights Landing Ridge Cut (KLRC), and migrate up into the Colusa Basin via the Colusa Basin Drain where they will be lost. In spring 2013, many Winter Run salmon were found stranded in the Colusa Basin under similar circumstances. The peak migration of Winter Run and sturgeon is in March and April. So I expect many salmon have or will be headed up the Ridge Cut, which is flowing 500-600 cfs.2 The CDFW trap is removed from the Ridge Cut outlet at such high flows.