Some salmon and sturgeon adults migrating up the Sacramento River this spring have had new help in passing upstream via the Yolo Bypass. With roughly half the Sacramento River’s flood waters flowing through the Yolo Bypass at the beginning of March, many salmon and sturgeon returning to the upper river to spawn likely chose entered the lower end of the Bypass at Rio Vista. These fish had a new notch opening to help them get over the Fremont Weir at the upper end of the 40-mile-long Bypass (Figure 1) and back into the Sacramento River to continue their journey.

The new $6-million gated-notch opening in the Fremont Weir is the first of several to be built into the two-mile-wide weir to help fish passage. The notches will allow an easier passage route over the weir, especially for large sturgeon. The notches are especially important in allowing an extended period for adult fish to finish their passage through the Bypass when Sacramento River water levels fall and the river flow ceases spilling over the weir into the Bypass. In the past, these conditions would have trapped any fish that remained in the Bypass. The notches will also help pass downstream-migrating juvenile salmon to enter the Yolo Bypass, where there is potential beneficial tidal and floodplain rearing habitat.

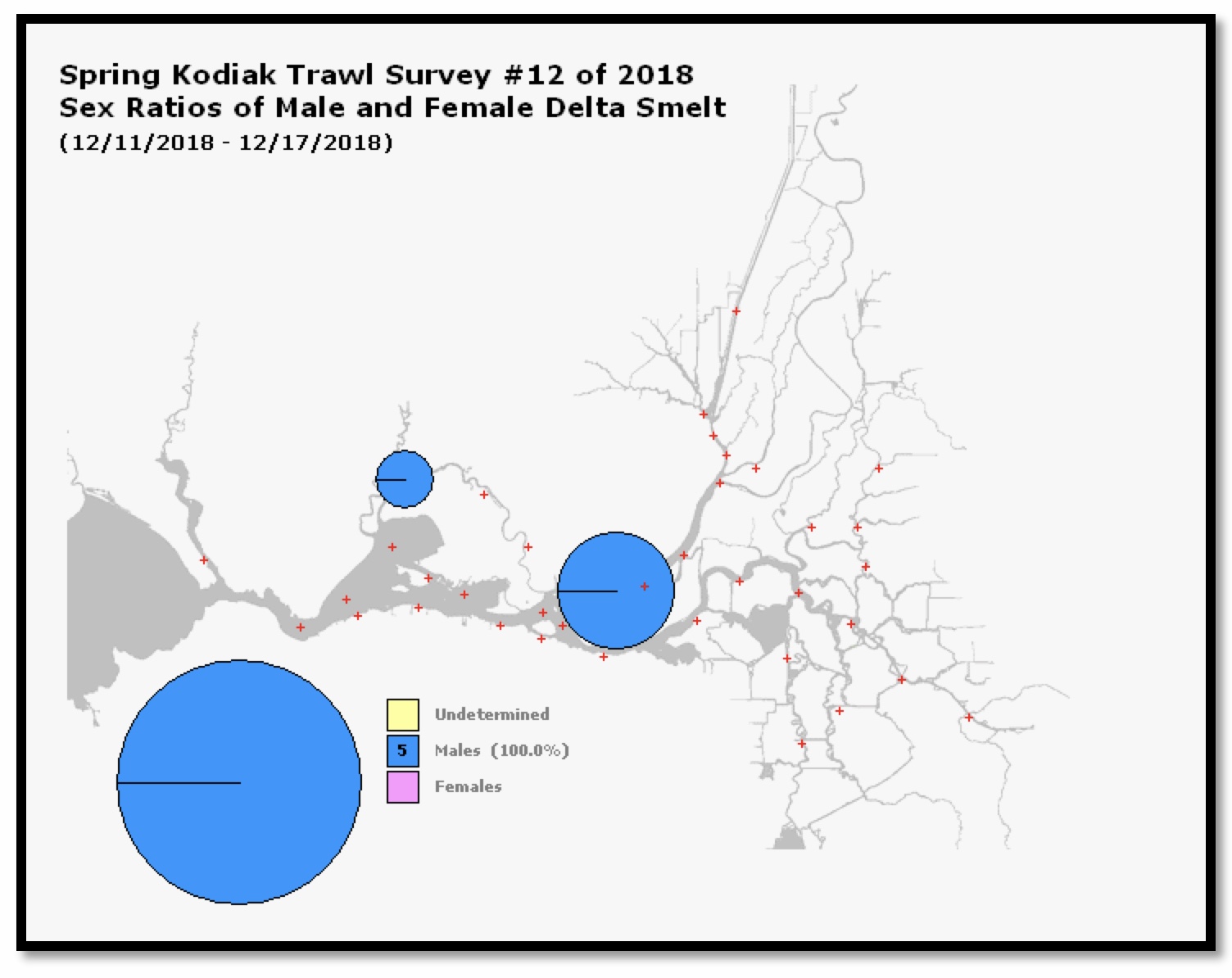

The first year of the new notch’s operation has not been without some glitches.1 Significant numbers of salmon and sturgeon have died and probably continue to die at the weir and in the Bypass.

But the new notch was not the underlying cause of this problem. The problem lies in flood control and reservoir storage management in the Central Valley. Drastic reductions in river flow and water levels led to fish stranding in the Bypass, the draining of the floodplain, and a rapid rise in water temperatures in the Bypass that stressed migrating fish.

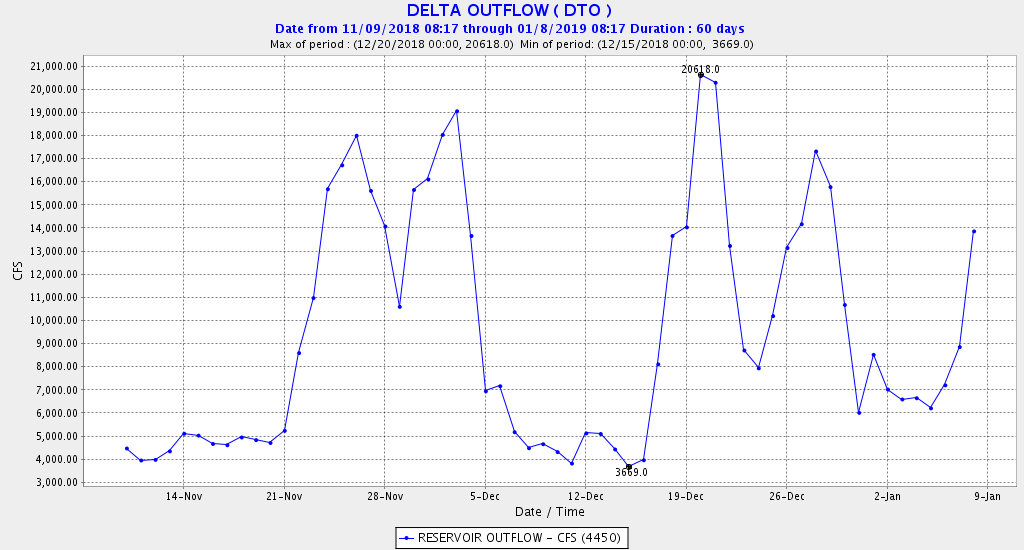

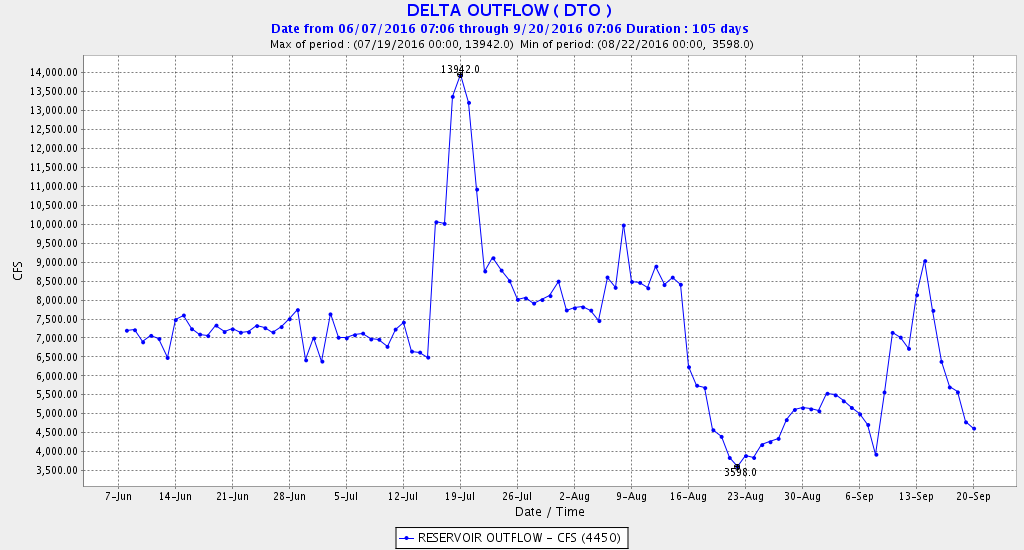

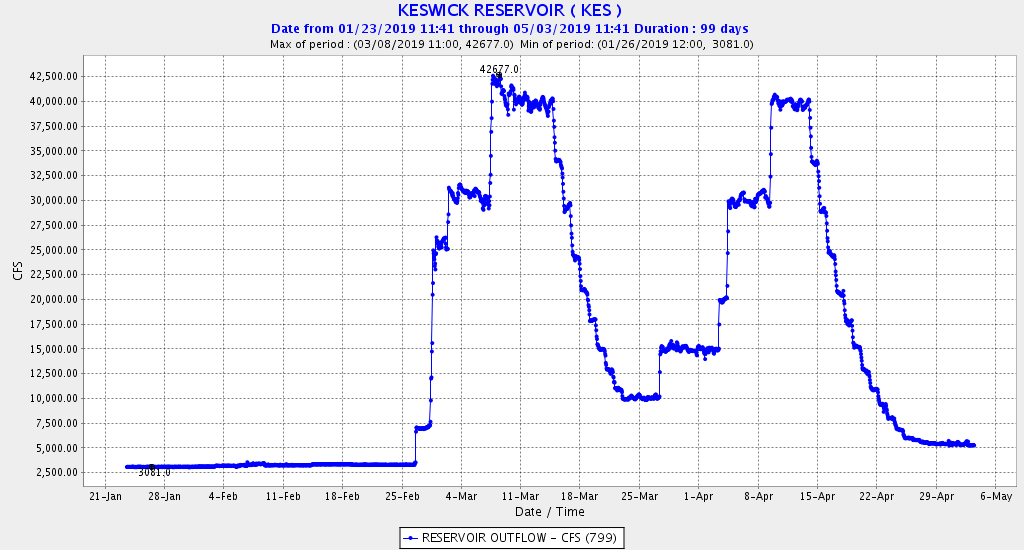

- Shasta/Keswick reservoir releases were reduced sharply after two major flood releases this winter/spring (Figure 2).

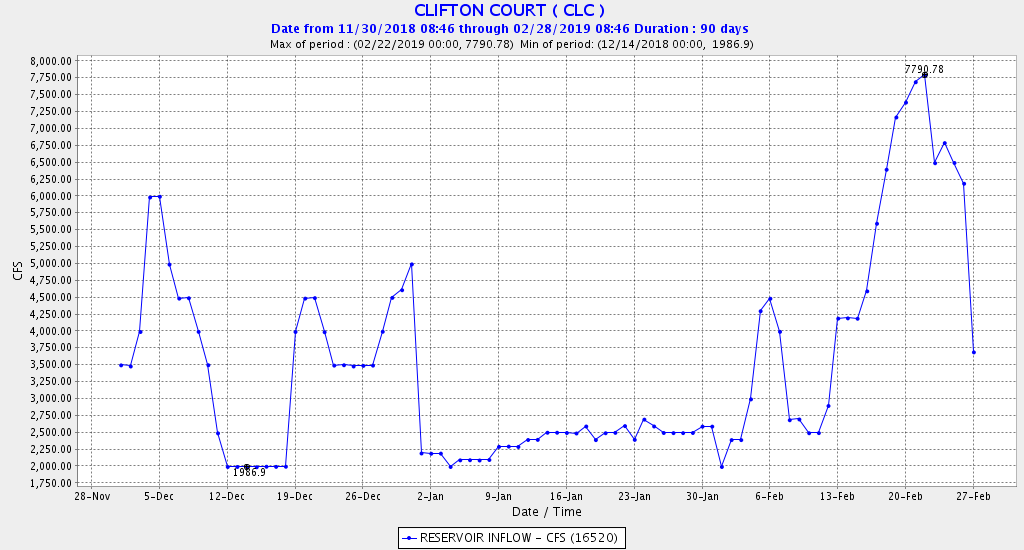

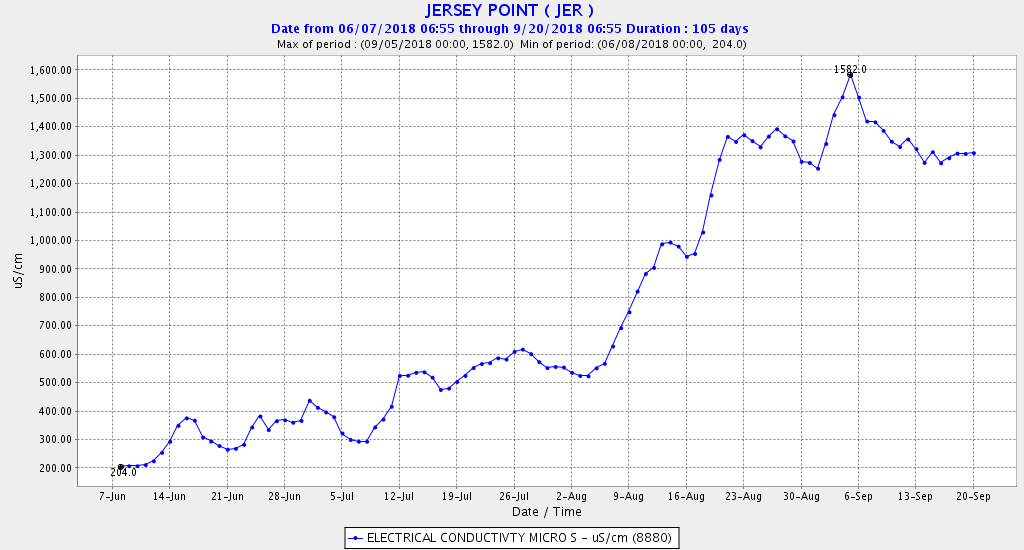

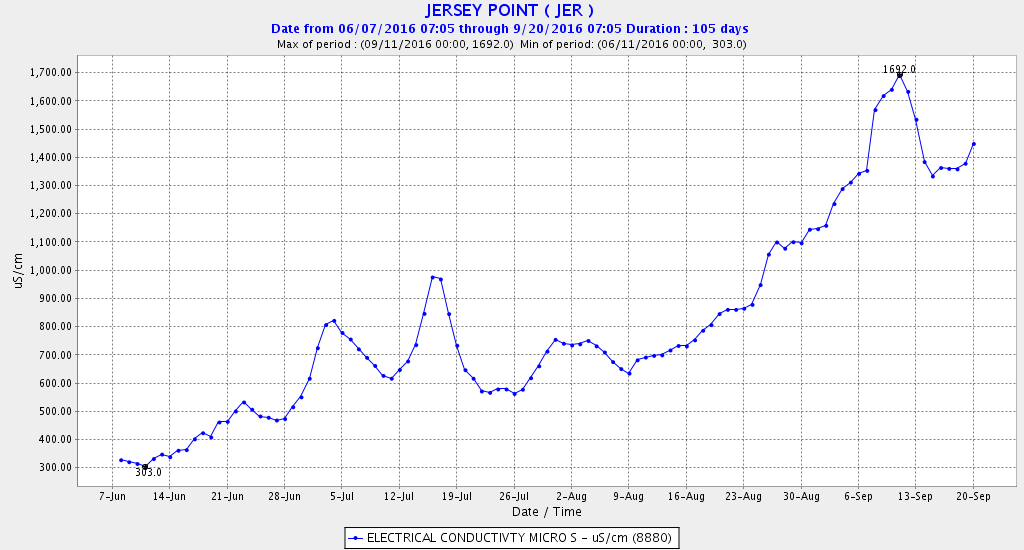

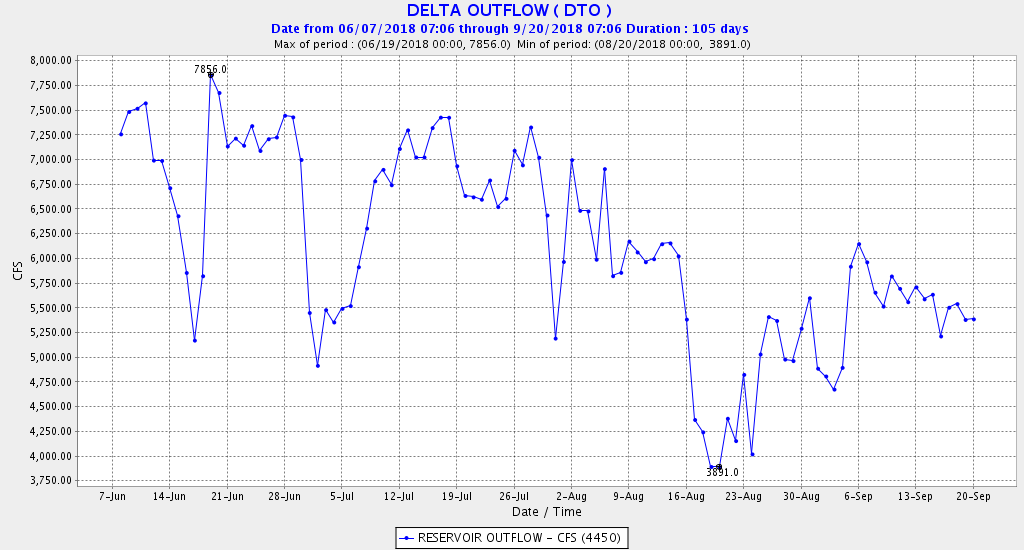

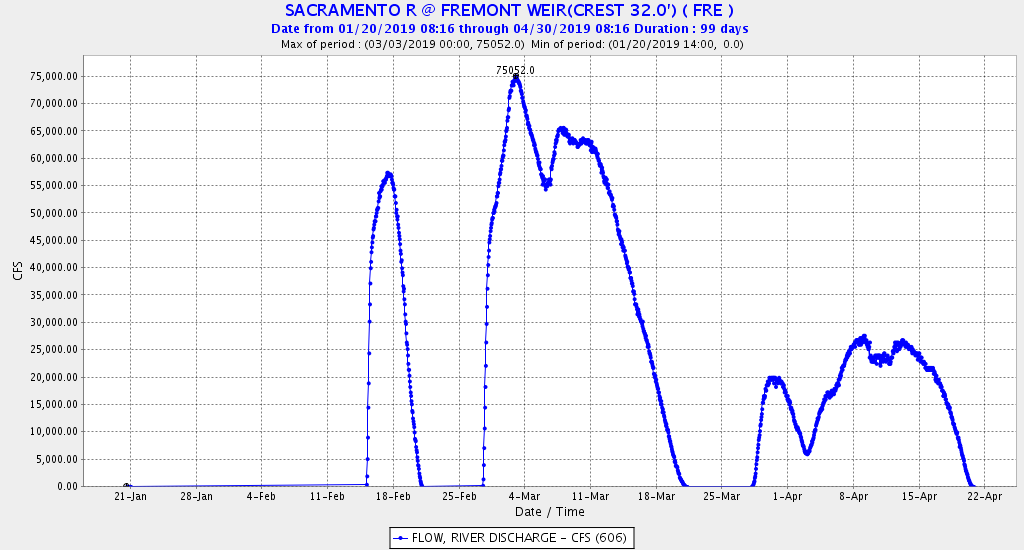

- This led to abrupt ends to Fremont Weir overflows into the Yolo Bypass (Figure 3)

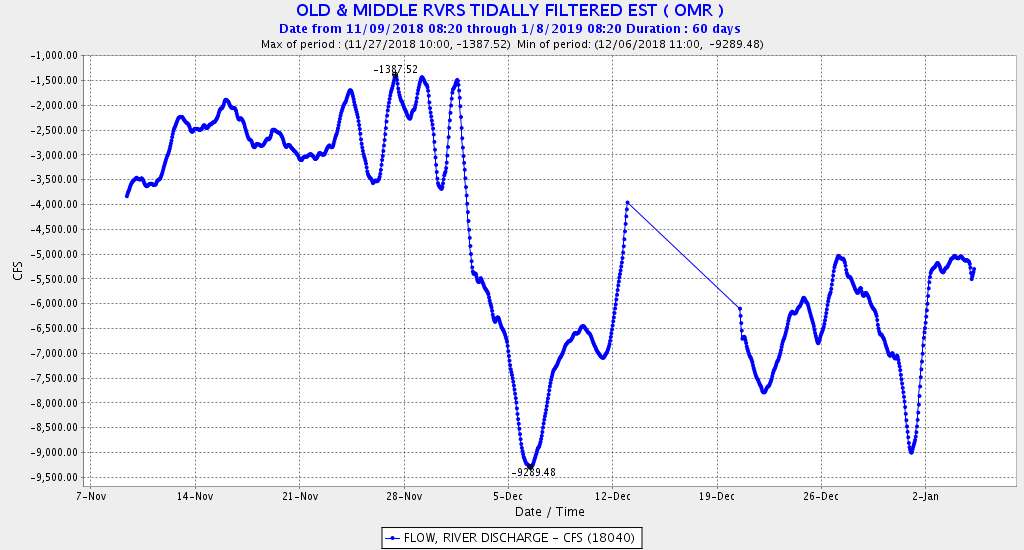

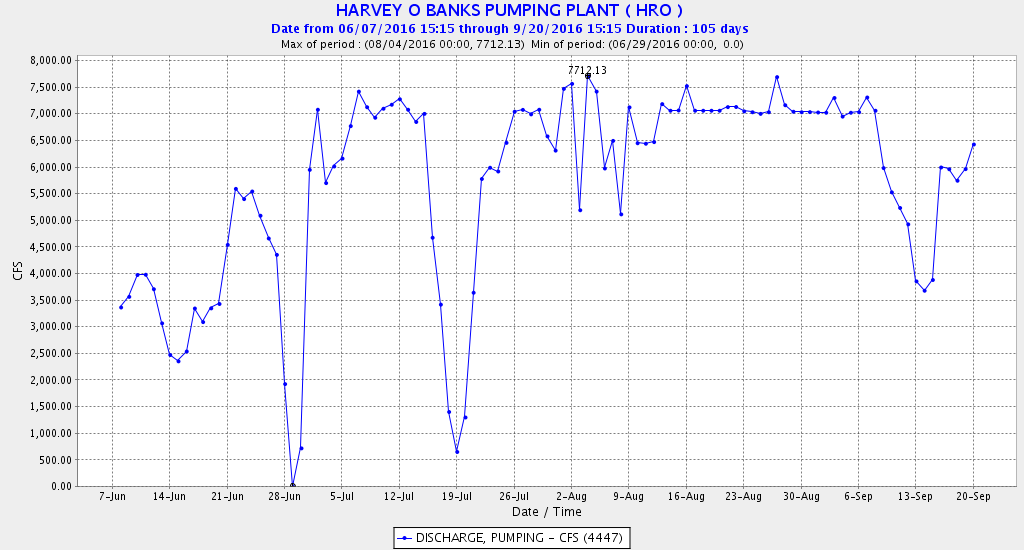

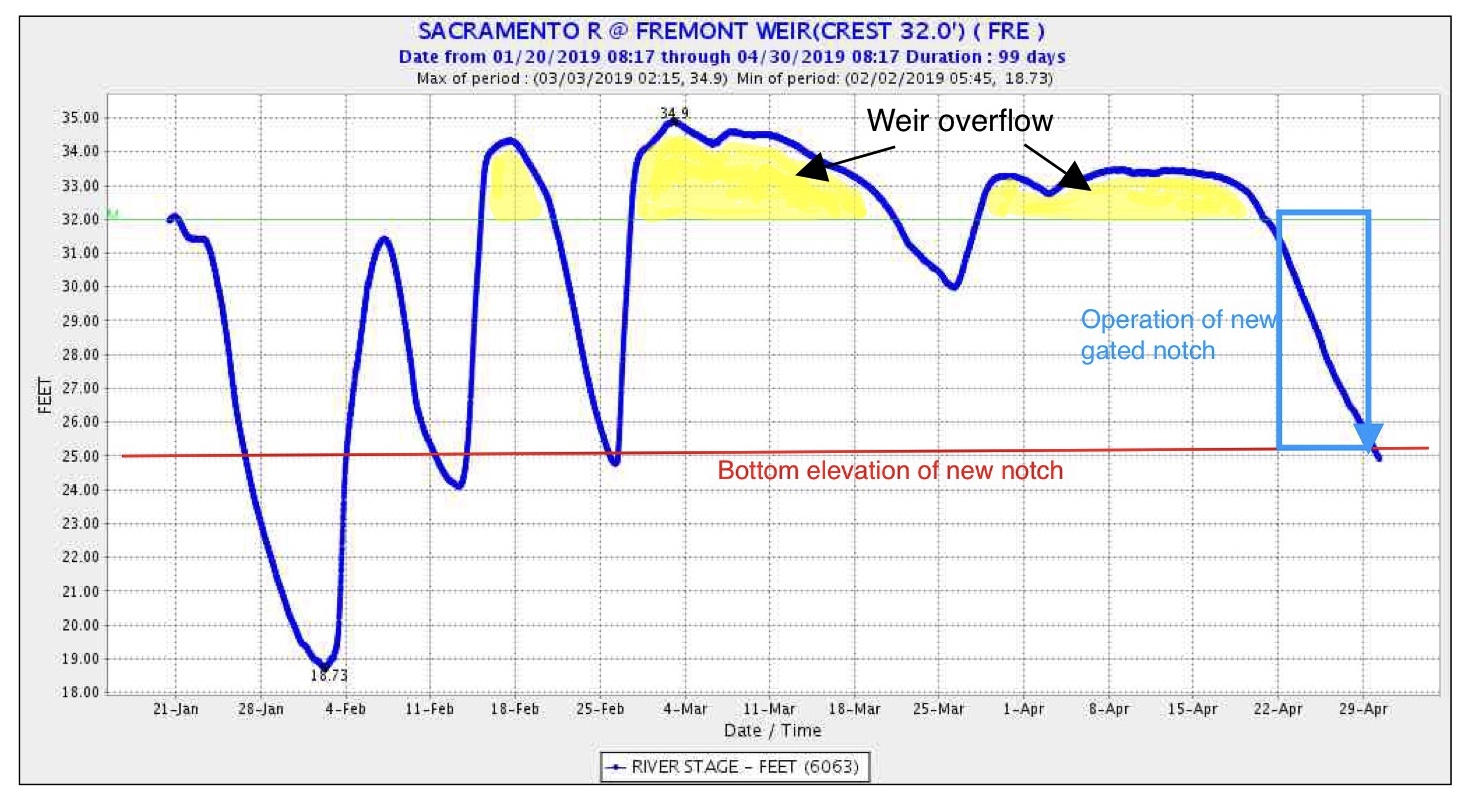

- The sharp drops in water levels in the river allowed only one week of extended Bypass inflows through the new notch (Figure 4).

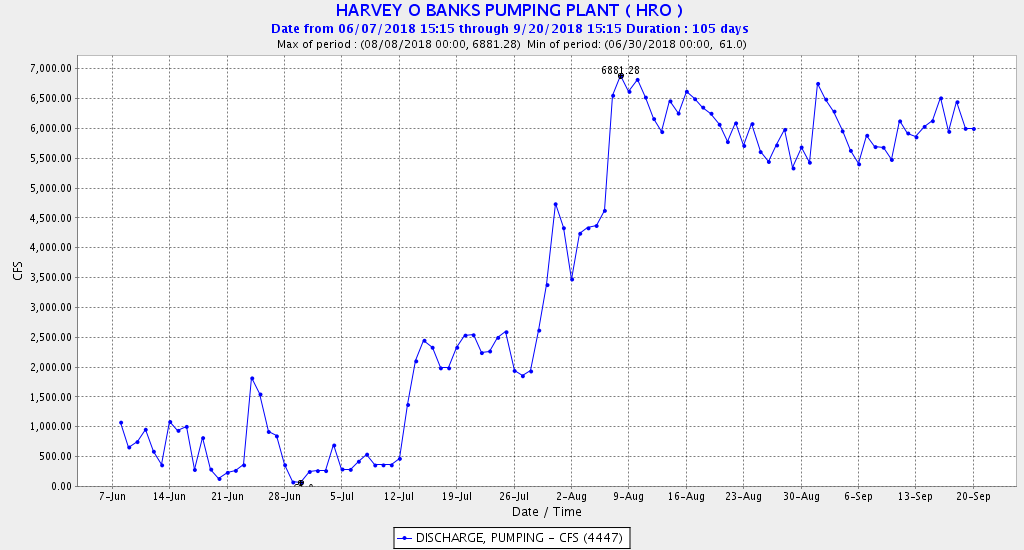

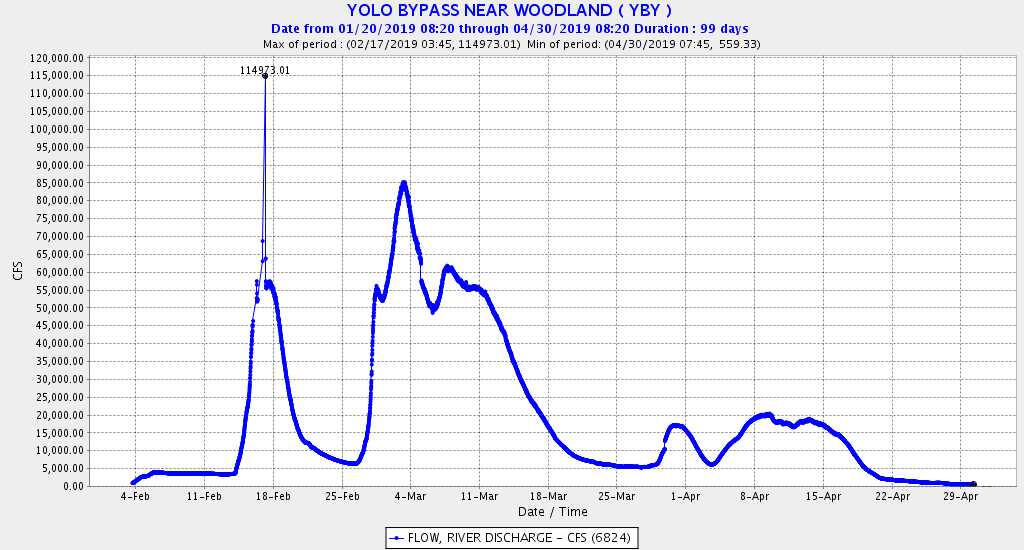

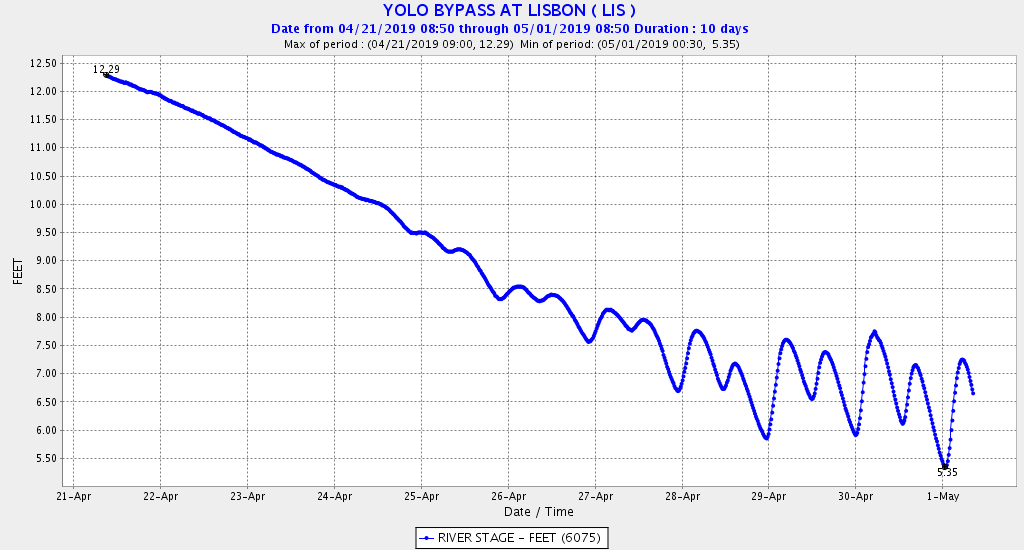

- That led to a rapid draining of the Bypass (Figures 5 and 6).

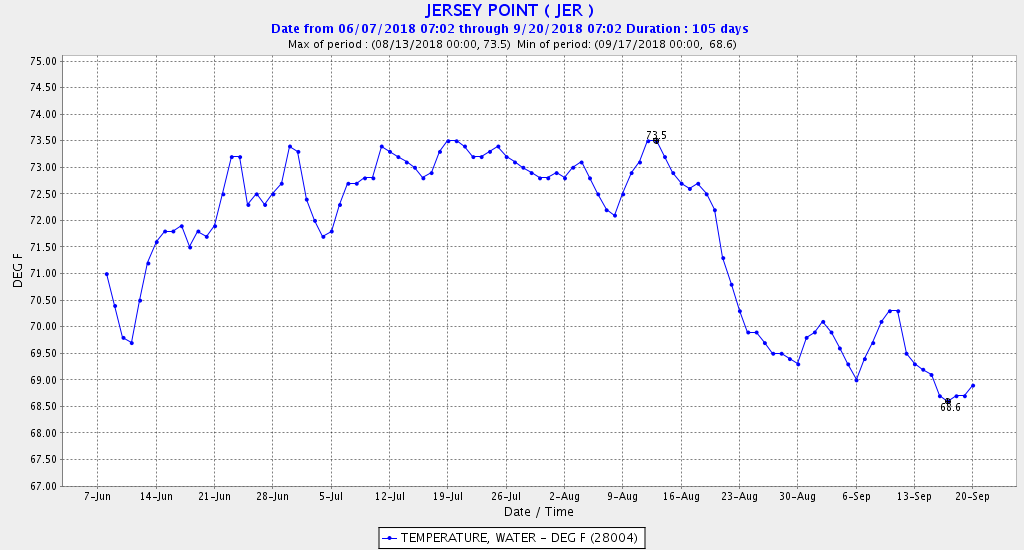

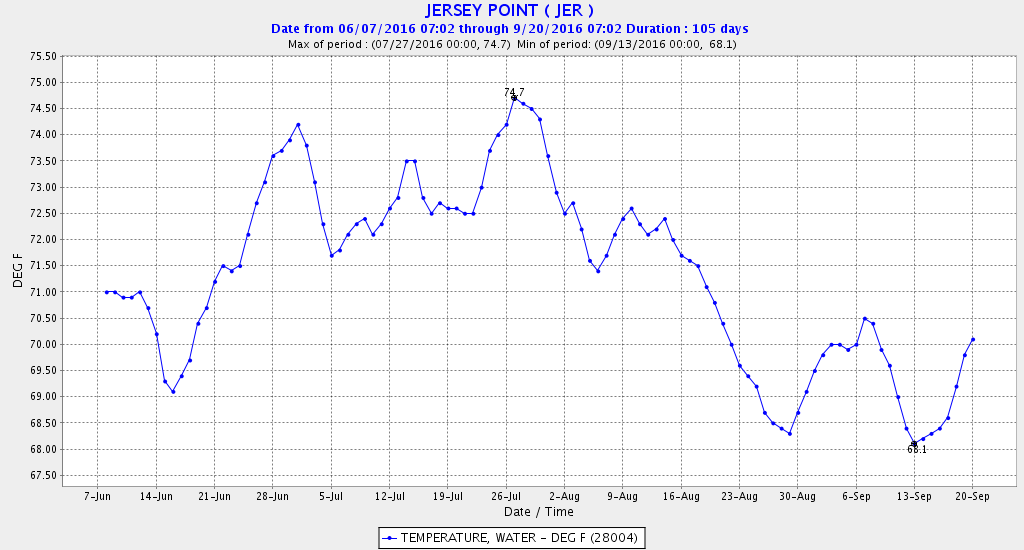

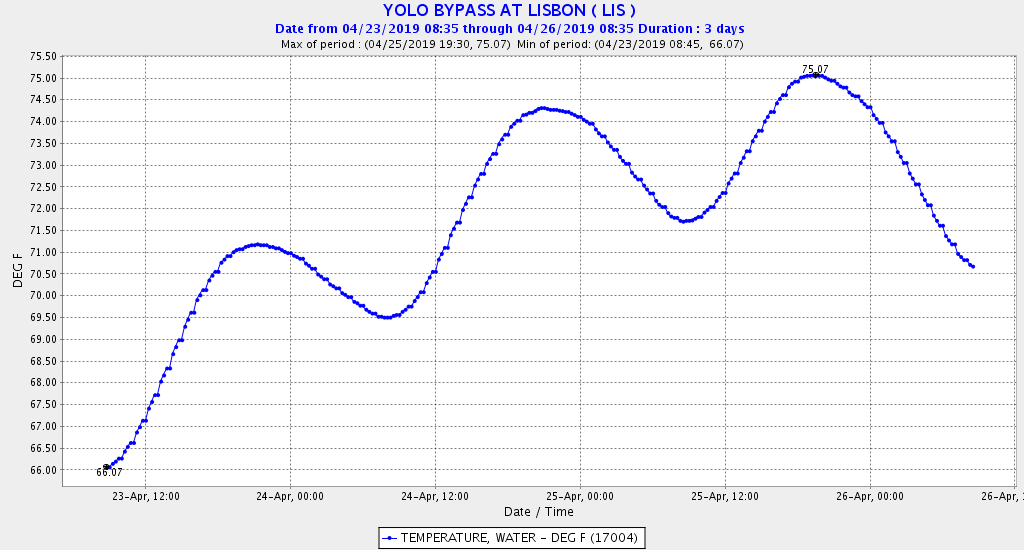

- This in turn led to excessive water temperatures in the Bypass (Figure 7) for migrating and rearing salmon (>70oF).

For the new notches to be effective, an extended period of flow through the new notches will be needed to allow time for migrating and rearing salmon and sturgeon to safely exit the Yolo Bypass without being subjected to a sudden draining of warm water from the shallow margins of the Bypass. With a near record snowpack and filling reservoirs, there were sufficient river flows and reservoir storage this year to extend the duration of river flows into the Yolo Bypass.

Figure 1. New Fremont Weir gated notch to help fish passage between Yolo Bypass and Sacramento River.

Figure 2. Reservoir releases from Shasta/Keswick dams in winter-spring 2019.

Figure 3. Flow into Yolo Bypass from Sacramento River at Fremont Weir in winter-spring 2019.

Figure 4. Water elevation of Sacramento River at Fremont Weir in winter-spring 2019. Top of weir is at 32-ft elevation. Bottom of new notch is at 25-ft elevation. Extended operation of new notch would have occurred from April 22-28.

Figure 5. Flow in upper Yolo Bypass in winter-spring 2019.

Figure 6. Water elevation in mid Yolo Bypass during Bypass draining in last week of April 2019.

Figure 7. Water temperature in mid Yolo Bypass at Lisbon Weir during Bypass draining in last week of April 2019.