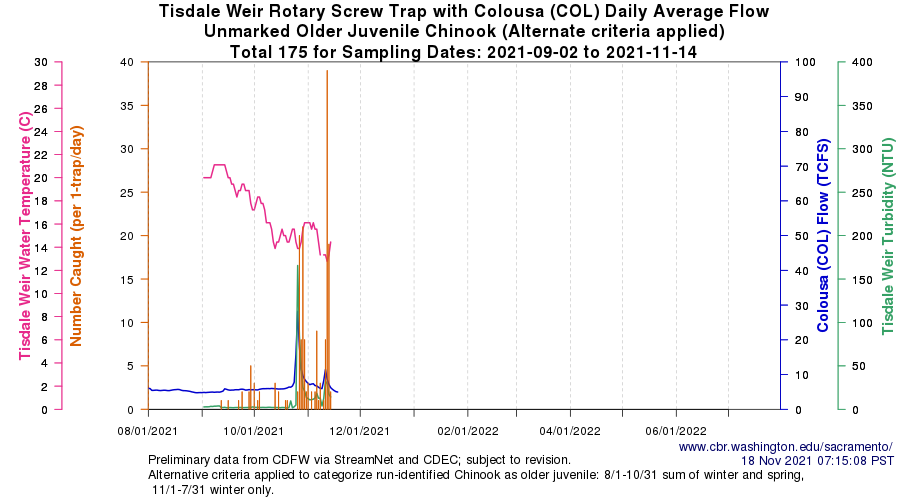

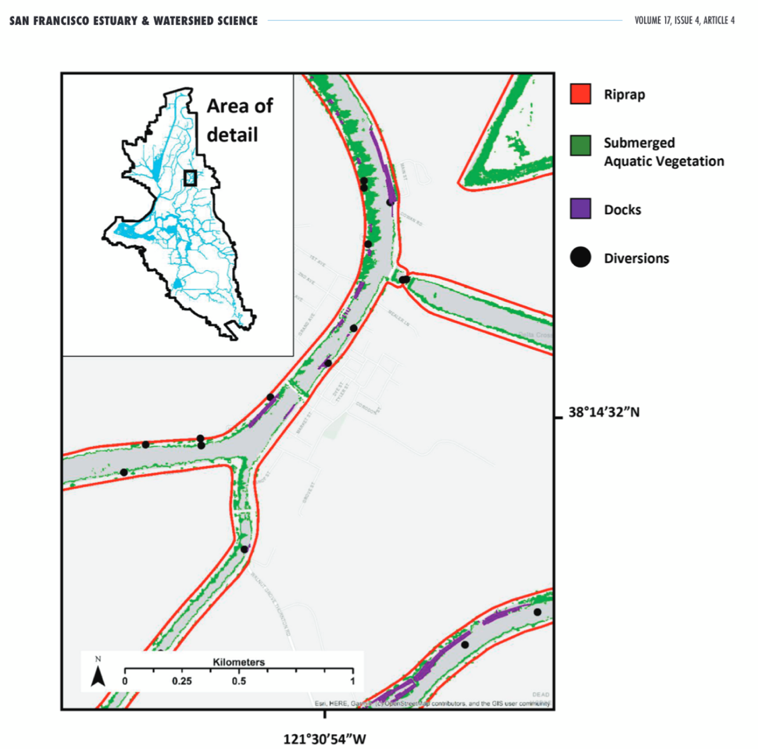

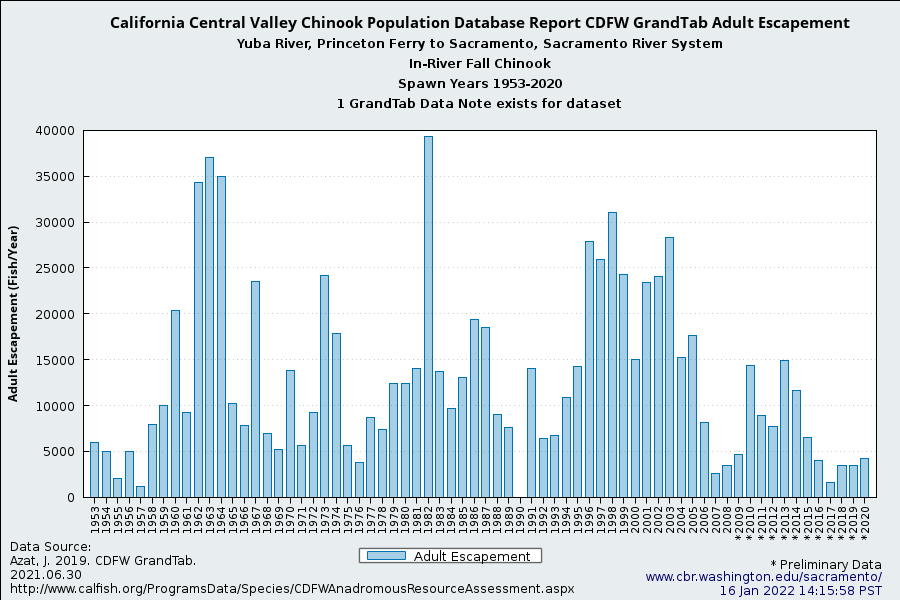

In a December 2020 post, I described the status of the fall-run salmon population in the Yuba River. Hatchery salmon predominate, while natural production is minimal. The population remains in a very poor state – at about 10% of recent historical levels during and subsequent to multiyear droughts such as 2007-2009 and 2013-2015 (Figure 1).

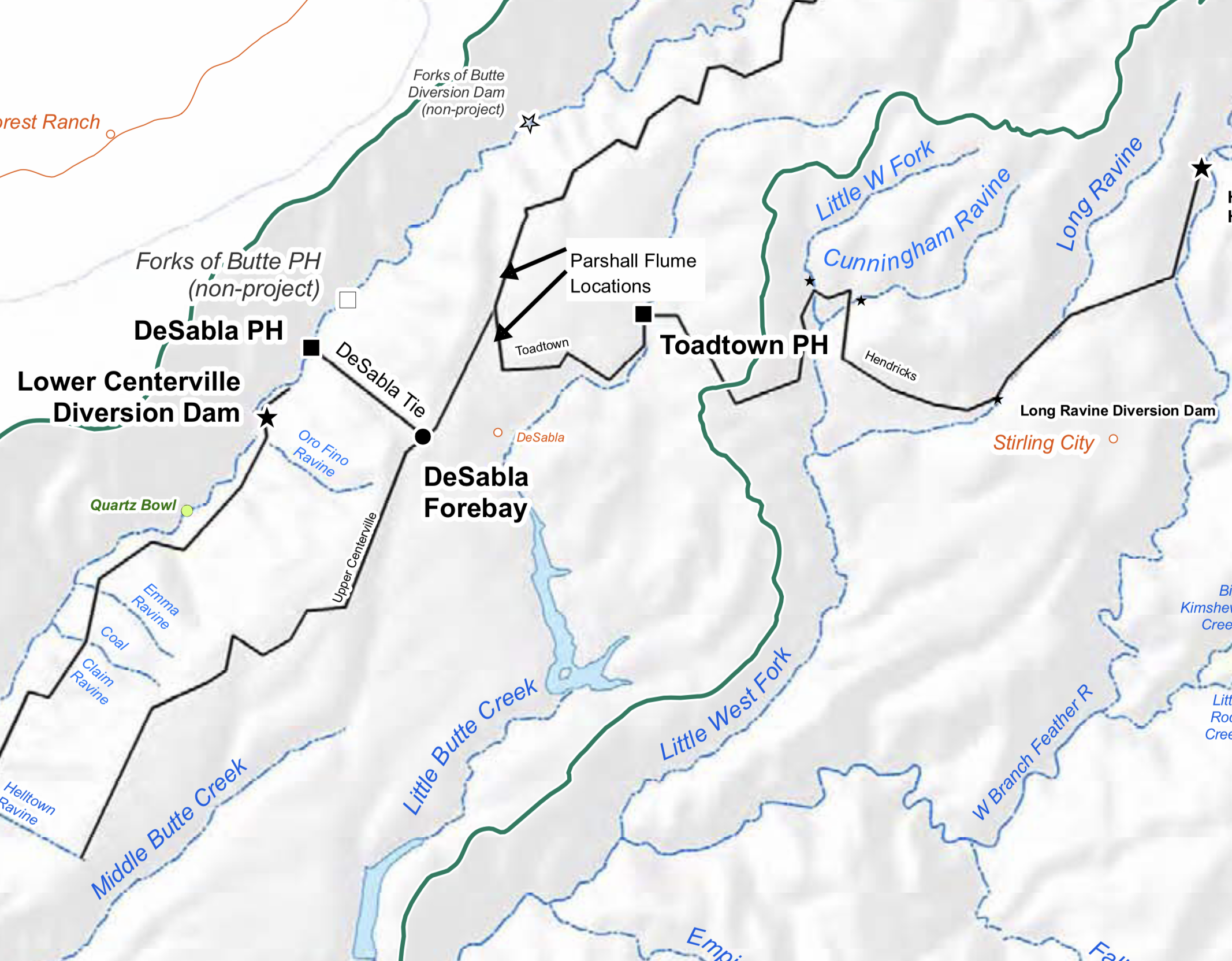

In a January 11, 2022 post, the South Yuba River Citizens League (SYRCL) promotes cleaning the two fish ladders at Daguerre Dam half way up the river to the impassable Englebright Dam, in order to provide better passage for spawning salmon to prime spawning habitat. Without effective ladders, salmon are delayed or even forced to spawn downstream of Daguerre Dam in marginal habitat. The ladders must be maintained per the federal NMFS biological opinion and take permit to operate Daguerre Dam as a water diversion dam for the Yuba County Water Agency (YCWA).

SYRCL’s plea to clean the fish ladders is helpful in bringing attention to the problems facing salmon (and steelhead) in the lower Yuba River. However, the fish ladders at Daguerre are only a small part of the problem for Yuba River salmon. River flows and habitat in the lower Yuba River need improvement.

River Flows

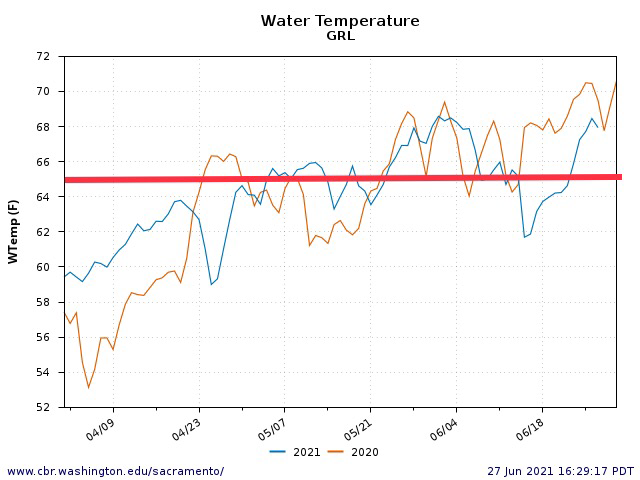

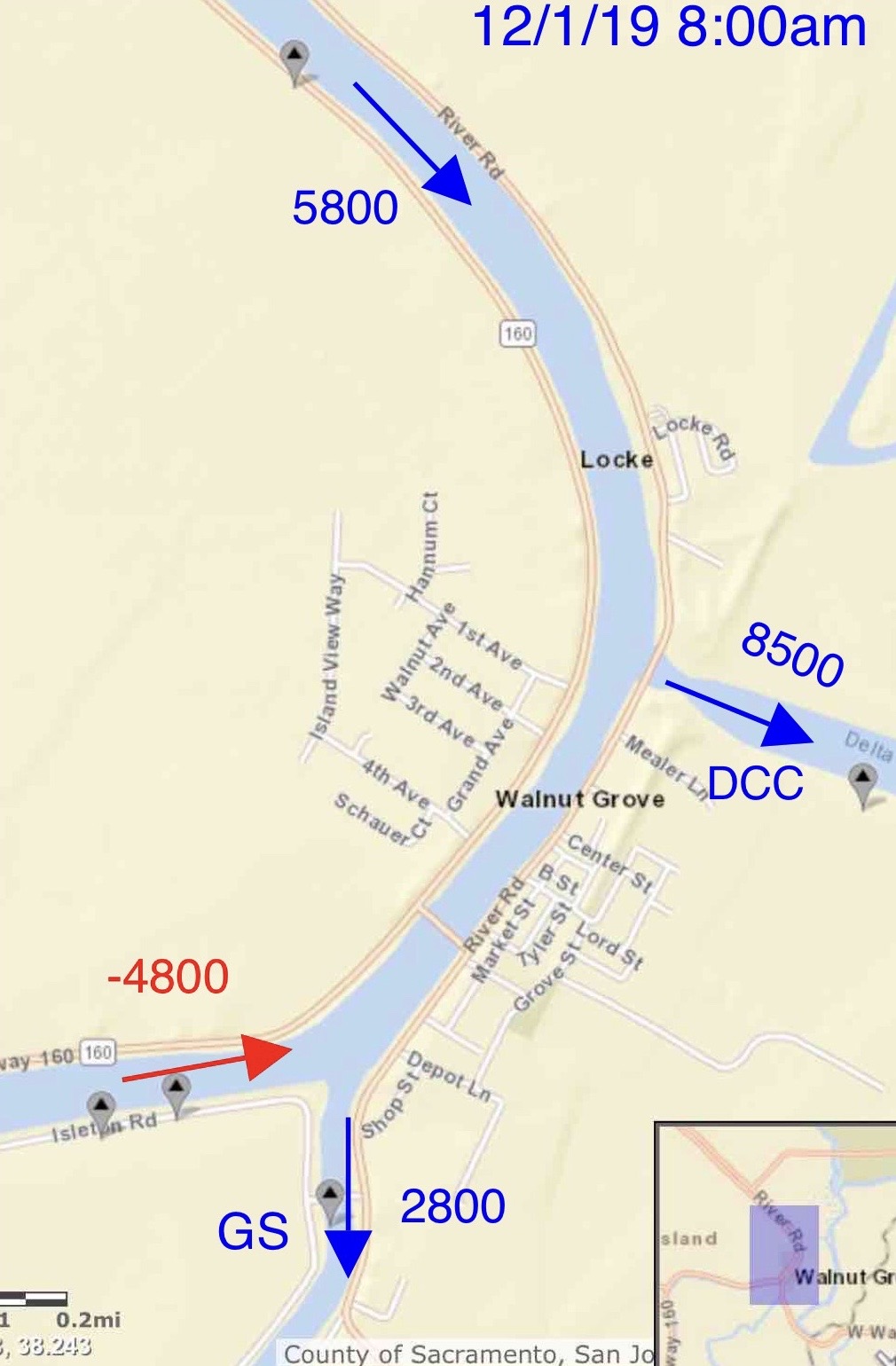

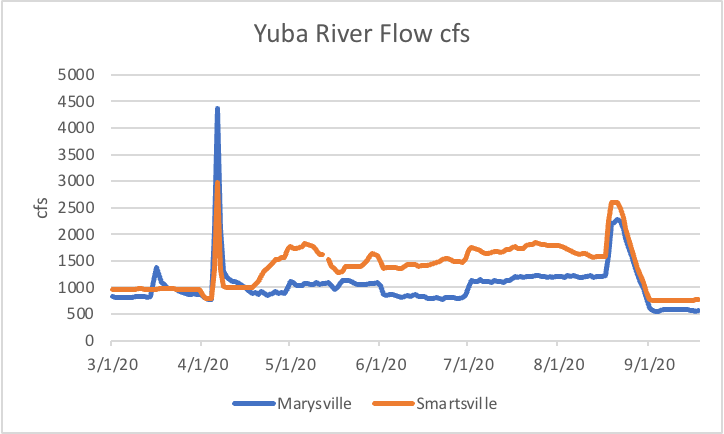

It is instructive to compare flows in 2020 (Figure 2) to flows in 2021 (Figure 3), particularly at the Marysville gage, where water has passed downstream of all the local agricultural diversions at Daguerre Dam.

2020

From May through mid-August of 2020, flows at Marysville averaged about 1000 cfs (Figure 2). The vast majority of this water was released through YCWA’s New Colgate Powerhouse upstream of Englebright Dam. In the fiscal year from July 1, 2020 to June 30, 2021, YCWA had revenues from power sales of over $80 million. 1 Water released during the summer creates more power revenue than flows released in spring.

Better management for fish would release more of the water in the spring, providing more areas in the lower Yuba River for juvenile salmon and steelhead to grow and higher flows to move them downstream when they are ready to leave the system. SYRCL, CSPA, and other conservation organizations, as well as staff from fisheries agencies, have recommended such a change in release pattern during the ongoing relicensing of YCWA’s hydropower project.

Some of this water released in the summer of 2020 was also sold out of the watershed, generally to entities south of the Delta. In the fiscal year ending June 30, 2021, YCWA also made $12 million on water sales.2 The large flow increase at the end of August 2020 – likely a water sale – had no benefit for fish. Its biggest effect on fish was that It drew down storage in New Bullards Bar Reservoir, which created a cascading effect in the very dry year 2021, when flows for all purposes were limited by lack of stored water.

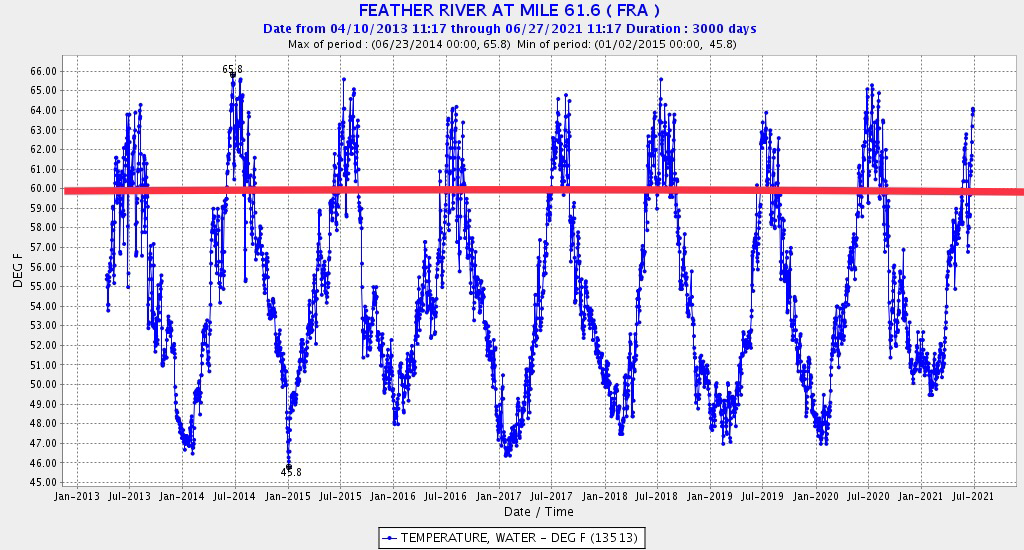

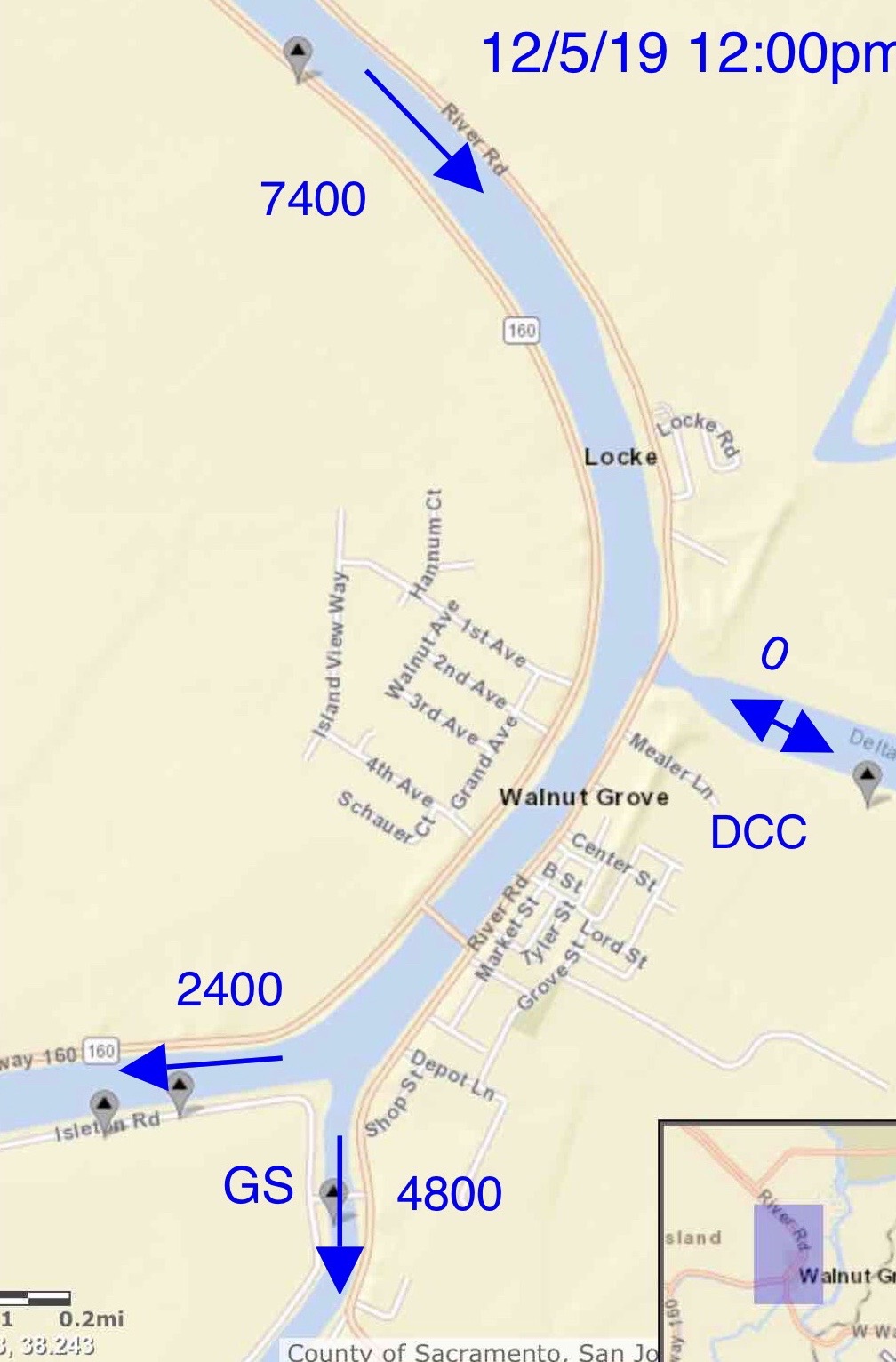

2021

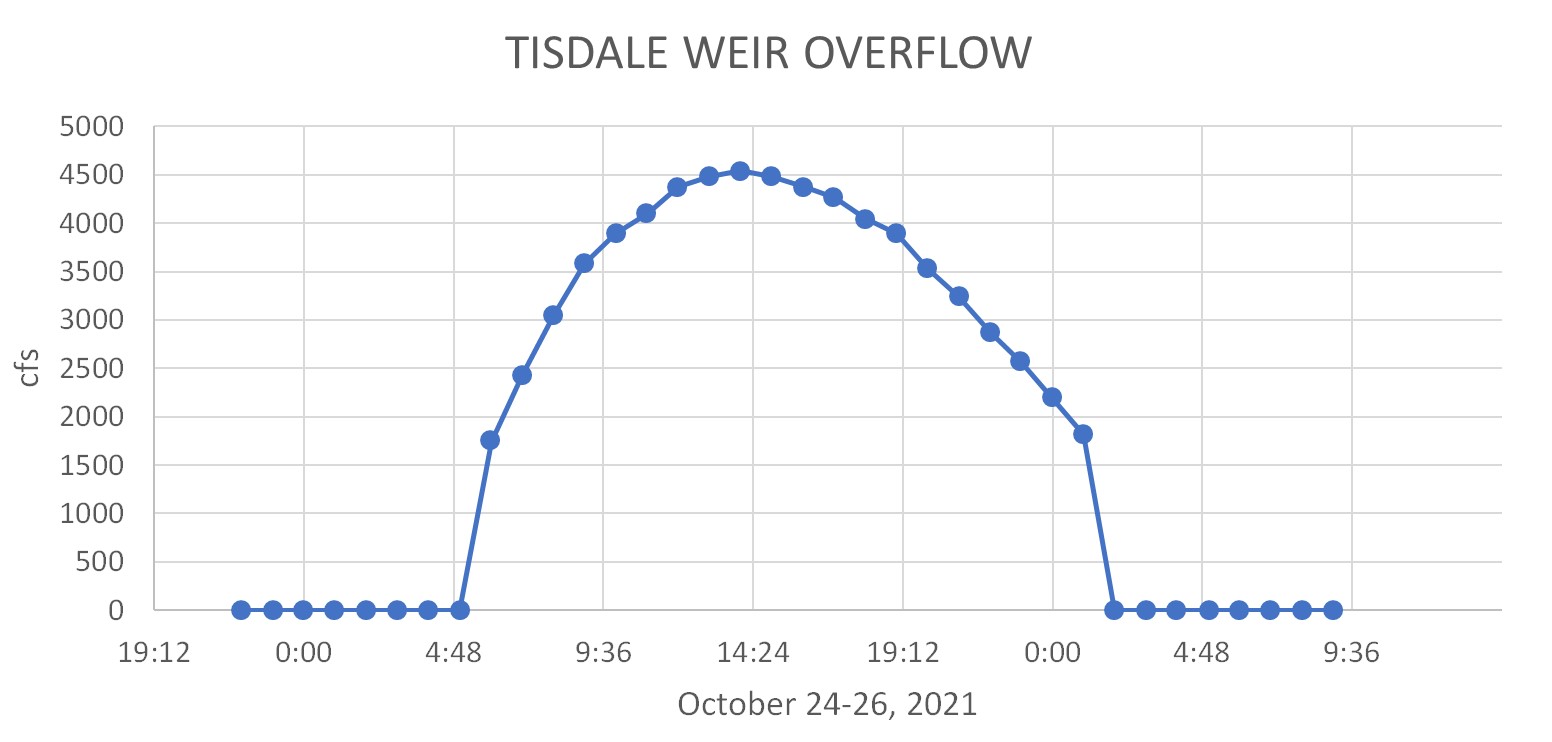

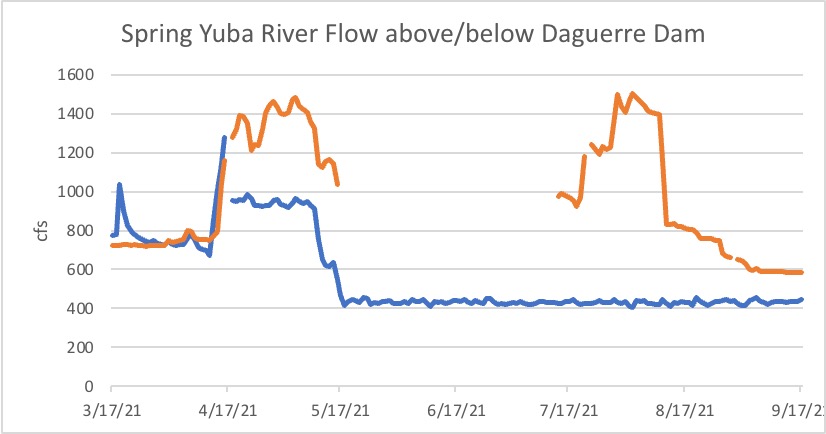

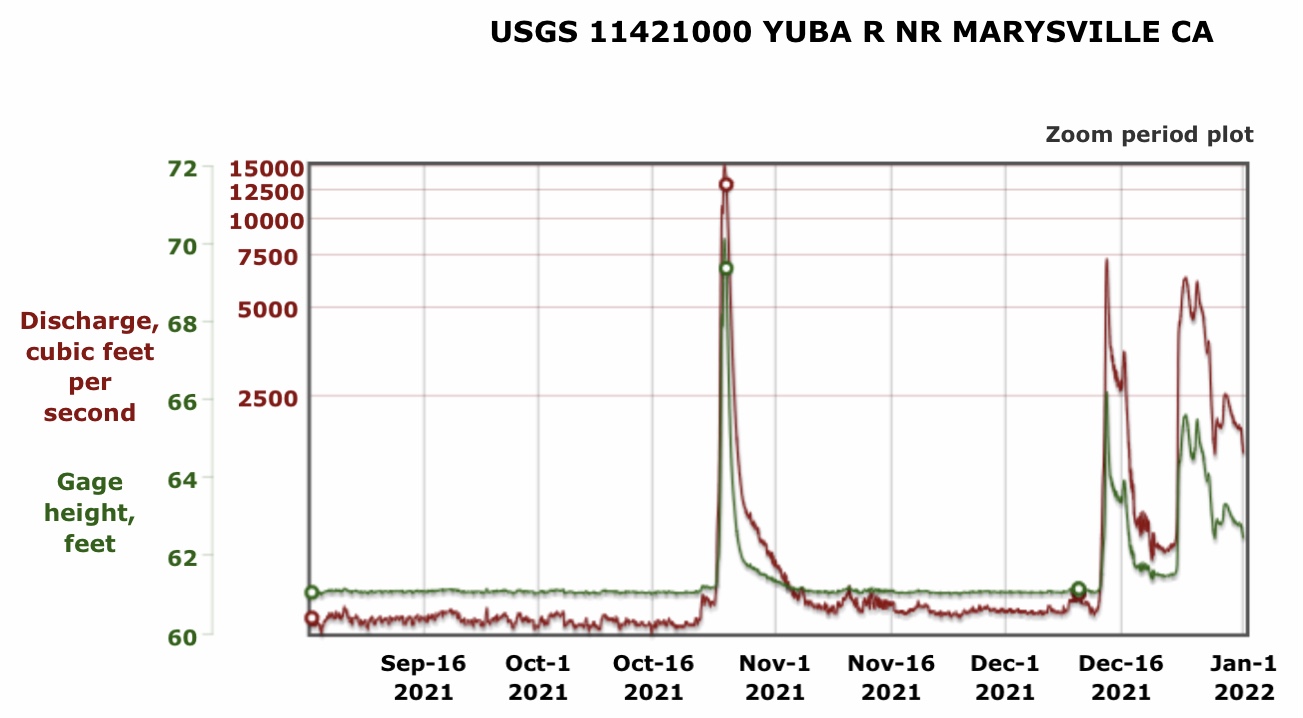

In a very dry year like 2021 that follows a dry year like 2020, river flows in spring and summer (Figure 3) become a major limiting factor. First, there are no late-winter, early-spring flow pulses to attract adult spring-run salmon. At a flow of 400 cfs at the bottom end of the lower Yuba River, there is insufficient flow to help adult spring-run salmon move upstream through many shallow riffles and through the Daguerre ladders. Very low late-summer and fall low flows likewise hinder fall-run salmon. Second, flows in late winter and early spring are too low to efficiently carry juvenile salmon downstream while avoiding the many predators on their way to the Bay and ocean. Downstream of Daguerre Dam, over-summering juvenile salmon and steelhead must contend with low flows and associated stressful water temperatures. Additionally, spawning at 400 cfs flow leads to redd scour if fall rainstorms occur: a late-October storm in 2021 brought Yuba flows up to 15,000 cfs and raised water levels nearly 10 feet (Figure 4).

Habitat

Feeding and cover habitat in the lower Yuba River are virtually nonexistent. Predatory fish abound below Daguerre Dam. Floodplain off-channel habitat and woody debris are severely lacking, especially during when winter-spring river flows are relatively low. Many fall-run salmon spawn in poor spawning habitat below Daguerre. To its credit, YCWA has contributed on a voluntary basis to several habitat improvement projects in the lower Yuba River, including the ongoing restoration at Hallwood. However, it has vigorously resisted the establishment of regulatory requirements for additional projects.

Biological Opinion (BO)

Keeping the ladders clean is already a mandate.

- Measures shall be taken by the Corps to minimize the effects of debris maintenance and removal at the Daguerre Point Dam fish ladders.

- When Yuba River flows exceed 4,200 cfs, the Corps shall provide notifications to NMFS on the status of debris accumulations and fish passage conditions at the Daguerre Point Dam fish ladders.

- The Corps shall take action within 24 hours, or as soon as it is safe, to remediate fish passage conditions related to debris maintenance and removal at the Daguerre Point Dam fish ladders.

- The Corps shall, by January 31 of each year, report to NMFS an update on previous year’s debris maintenance and removal actions, including details on amount of debris removed, the timing of removal and the conditions that triggered debris accumulation.

- The Corps should consider predator removal at Daguerre Point Dam.

Summary and Conclusions

Flow regimes and habitat improvements are necessary to save Yuba salmon, in addition to ladder repairs and cleaning at Daguerre Dam. The Yuba River Accord, which has defined lower Yuba River flows since 2008, leaves too much flow in the summer by shorting flows that salmon and steelhead need in the spring. The channel of the lower Yuba River also needs extensive physical improvement.

Figure 1. Yuba River salmon escapement 1953-2020.

Figure 2: Yuba River flow (cfs) March 1 – September 15, 2020 above (orange) and below (blue)

Daguerre Dam.

Figure 3. Yuba River flow (cfs) March 15 – September 15, 2021 above (orange) and below (blue) Daguerre Dam.

Figure 4. River flow (cfs) and stage (feet) in lower Yuba River below Daguerre Dam near Marysville in fall 2021.

- See YCWA financial report for 2021 and 2020 at https://www.yubawater.org/Archive.aspx?ADID=310, pdf p. 14. ↩

- Id. Compare wet year 2019, with likely no out of basin water sales, and water sale revenues of $531 thousand. ↩