I last reported the status of striped bass in 2016. The prognosis was not good after four years of drought (2012-2015). Today, after a sequence of water years (2016-2019) that were below normal, wet, below normal and wet, the prognosis has not improved, notwithstanding the remarkable resilience of striped bass.

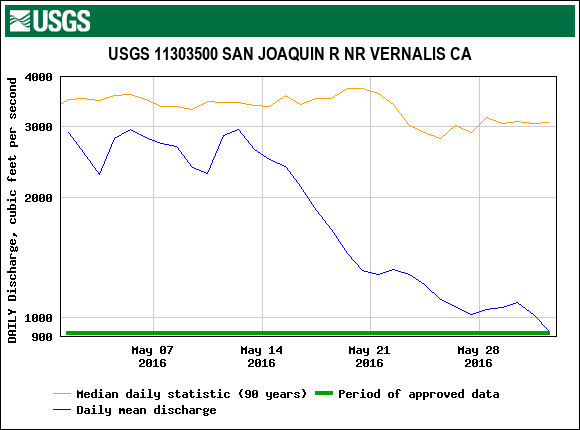

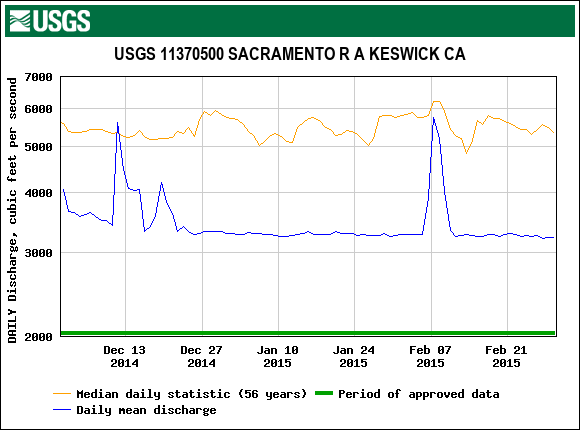

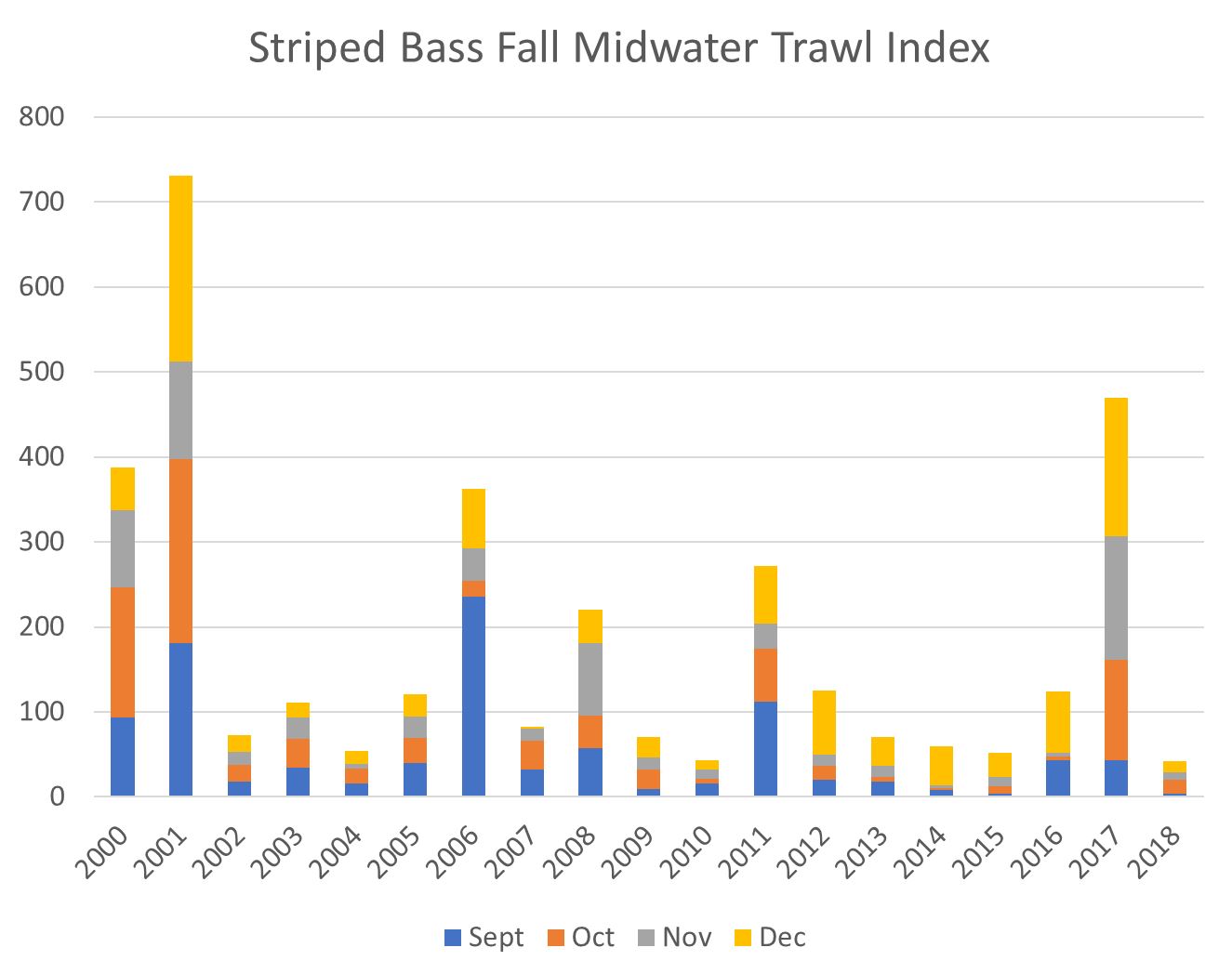

After improving in below-normal 2016 and wet year 2017, the below-normal 2018 fall index equaled that of below-normal 2010, the lowest since 2000 (Figure 1). A similar pattern occurred in the 2018 summer index (Figure 2).

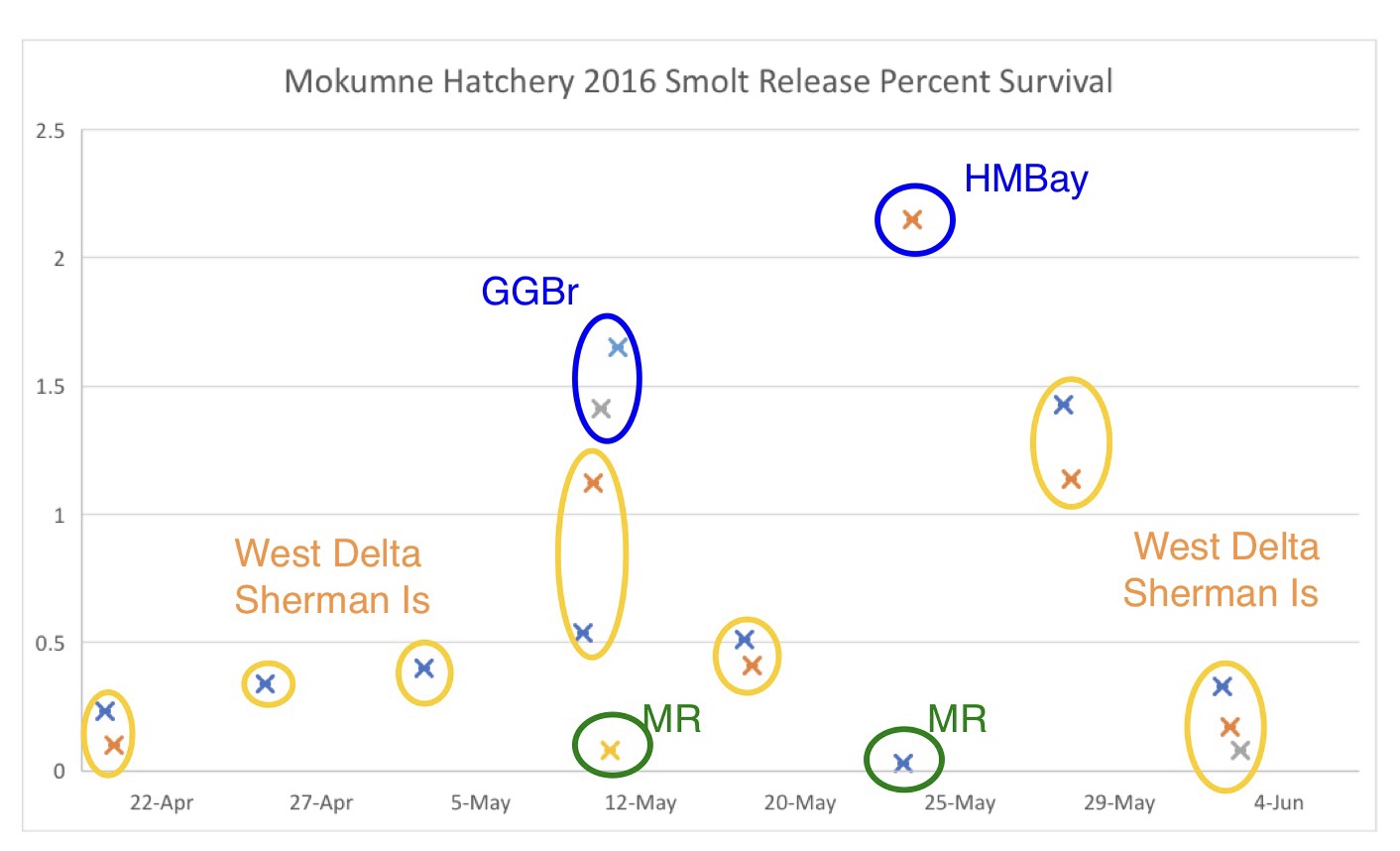

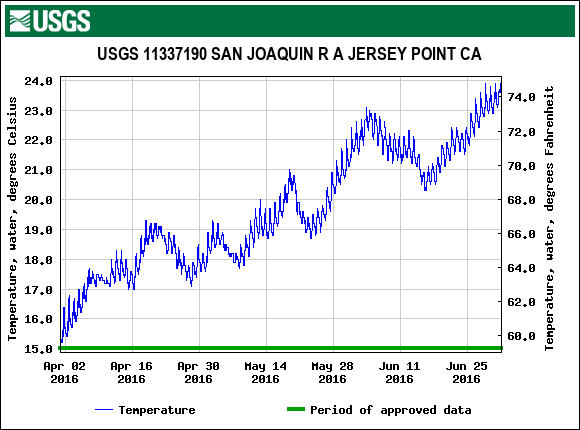

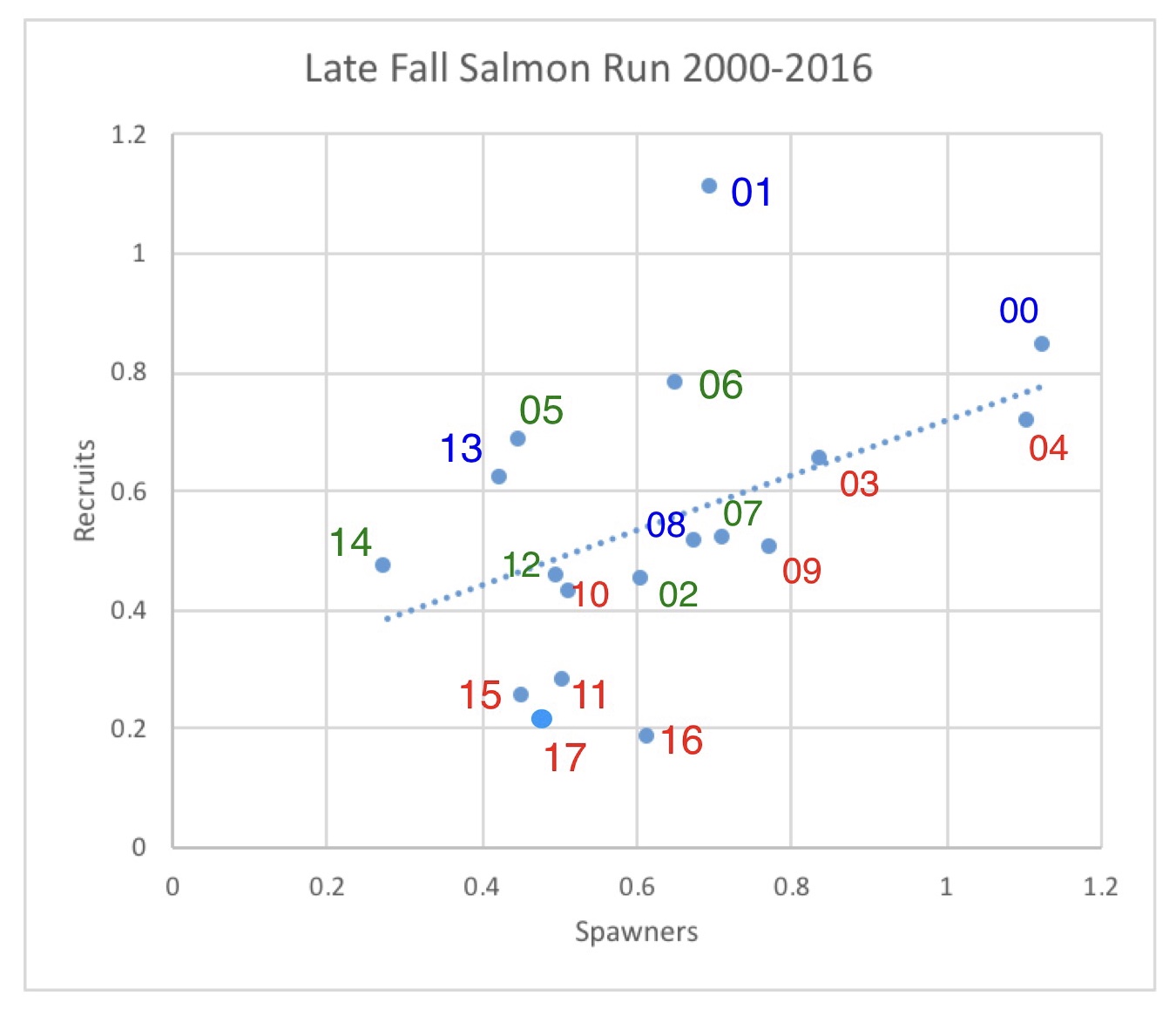

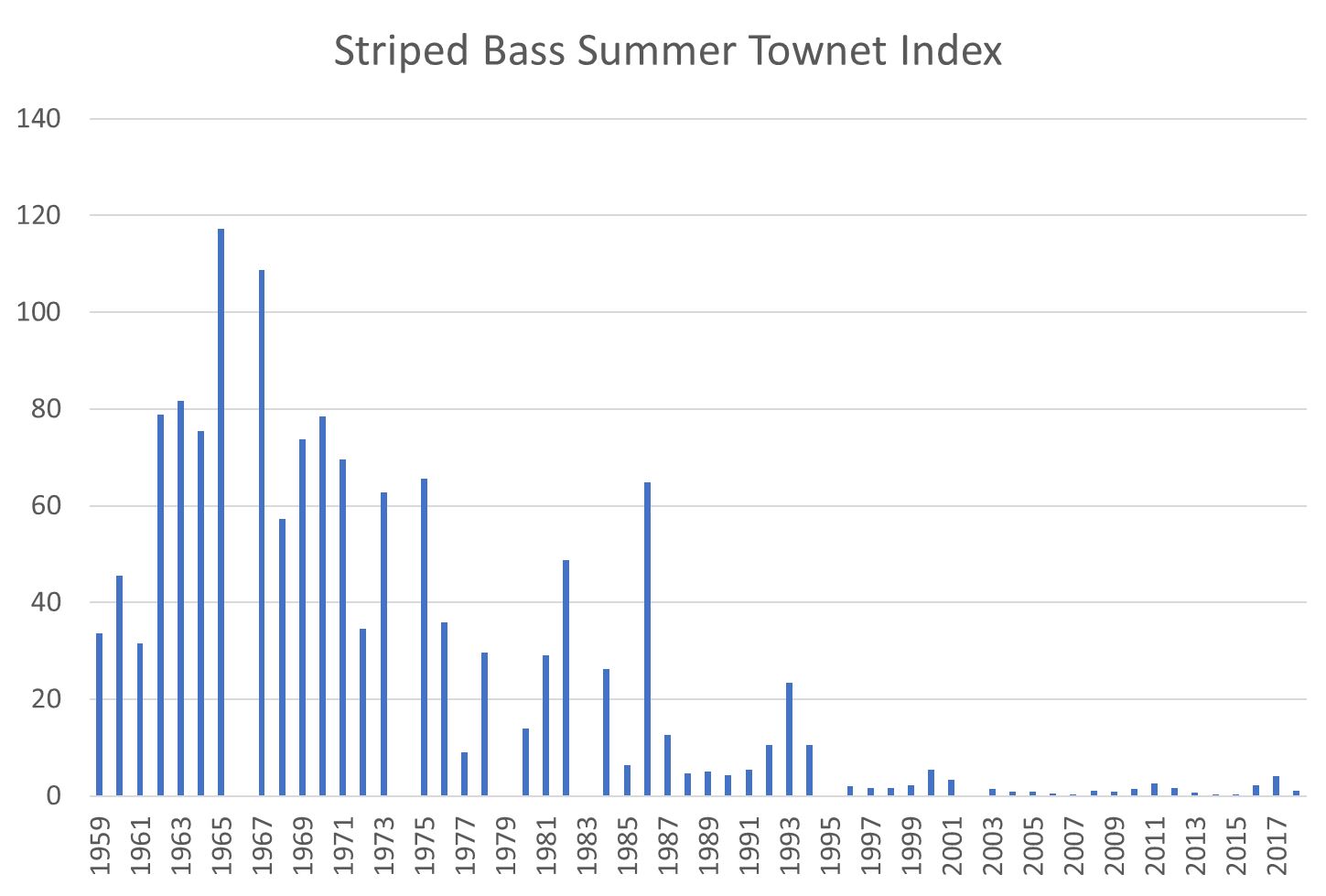

The summer-to-fall recruitment relationship (Figure 3) shows a continuing strong relationship between the summer index and fall recruitment. Furthermore, the relationship continues to show a positive response in wet years (2011 and 2017), but a poor response in the below normal years (2010, 2016, and 2018). This indicates that summer conditions in these below-normal water years is depressing the fall recruitment of striped bass.

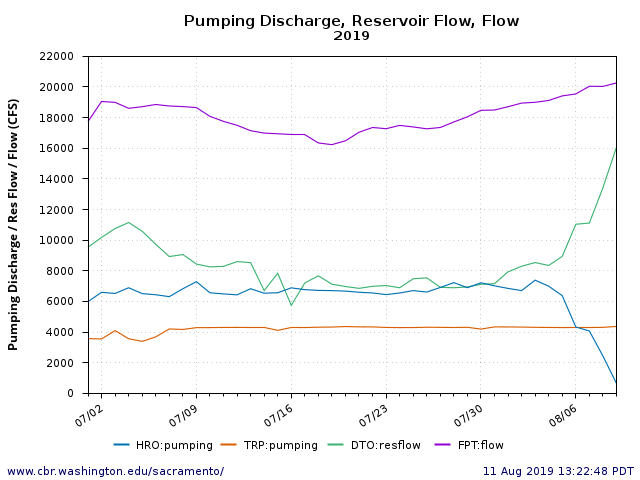

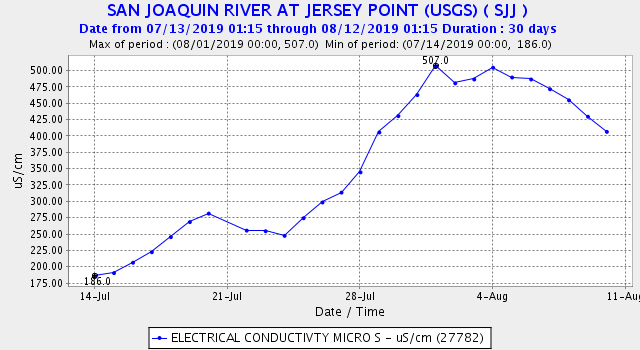

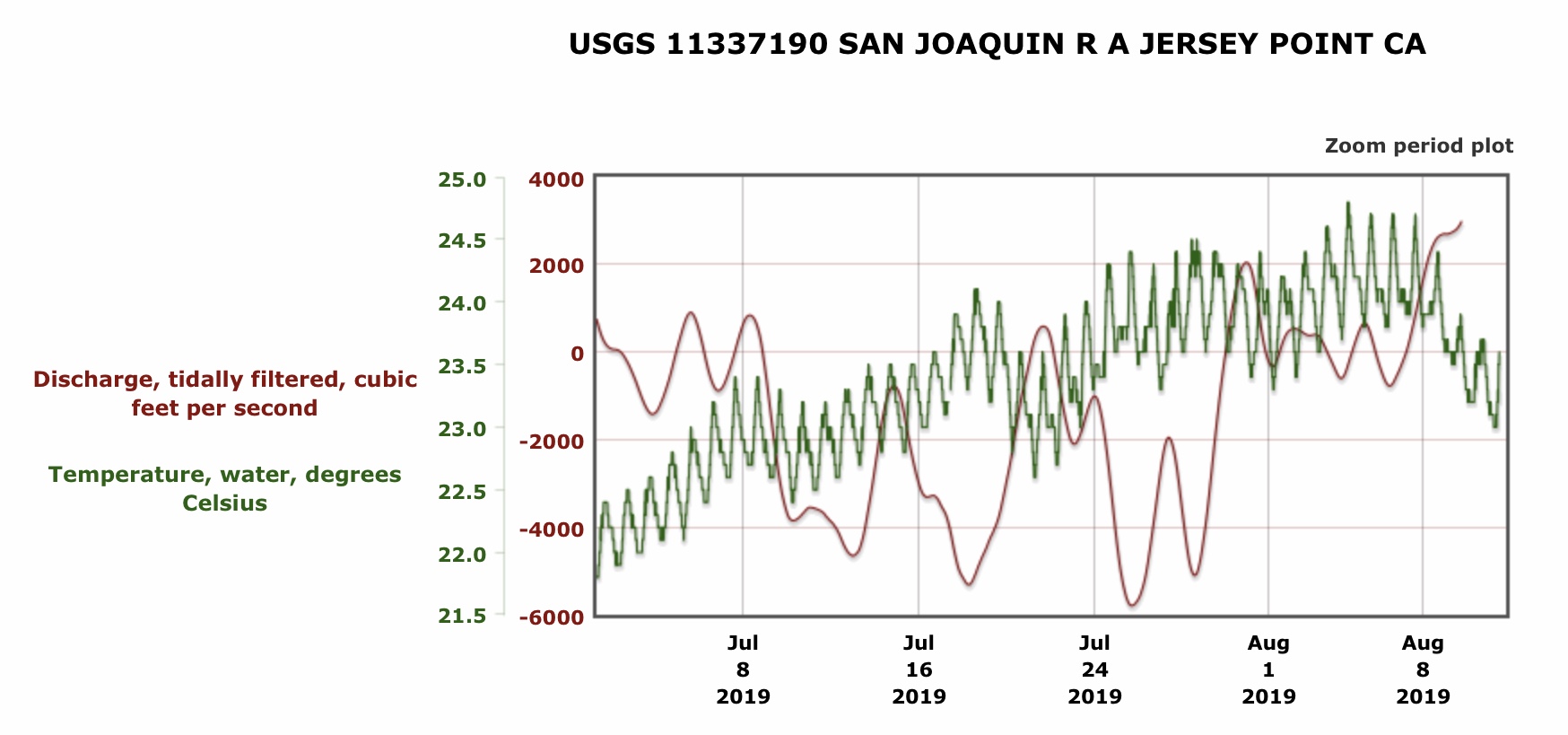

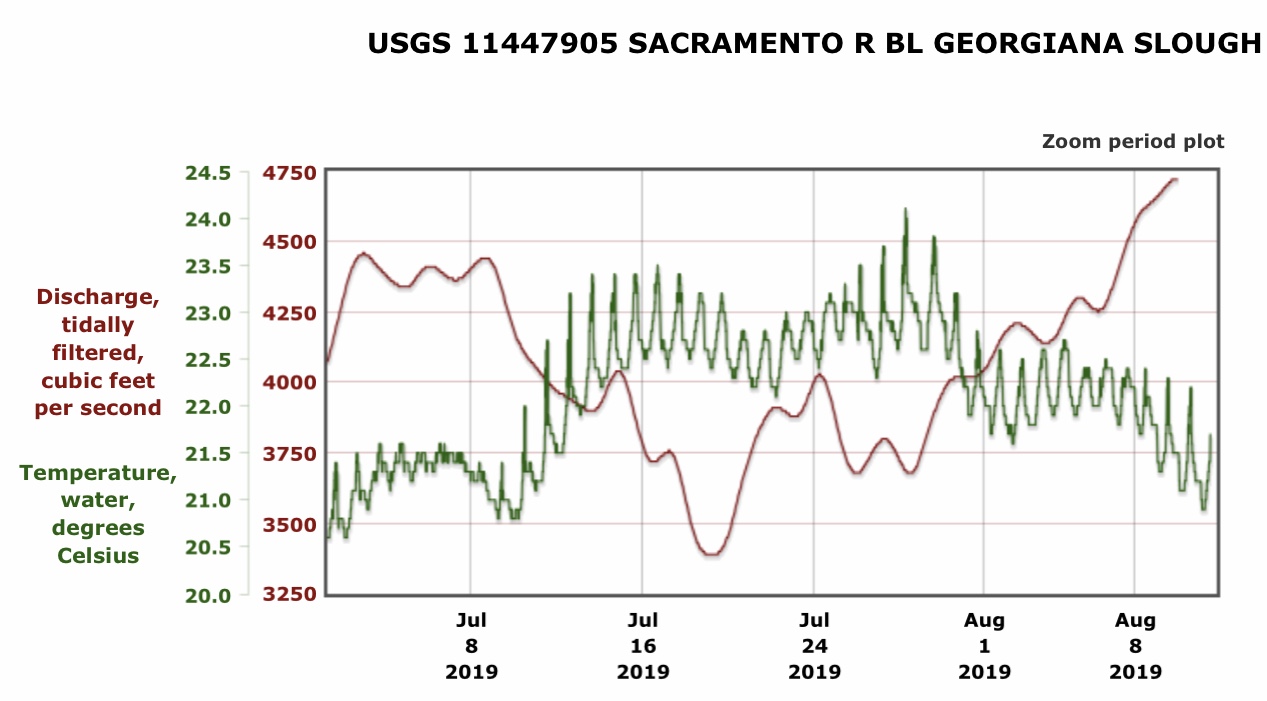

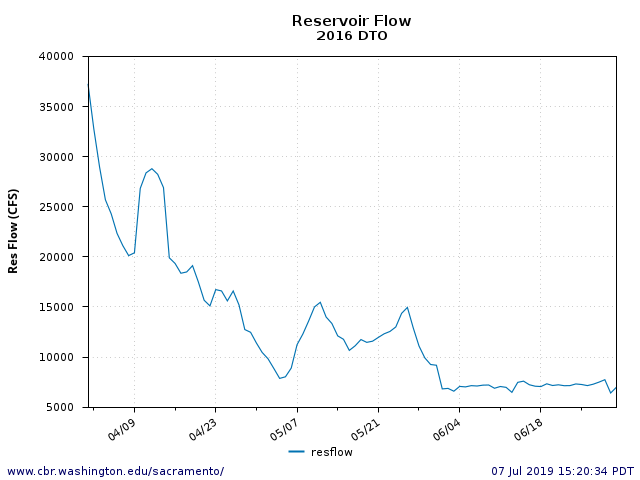

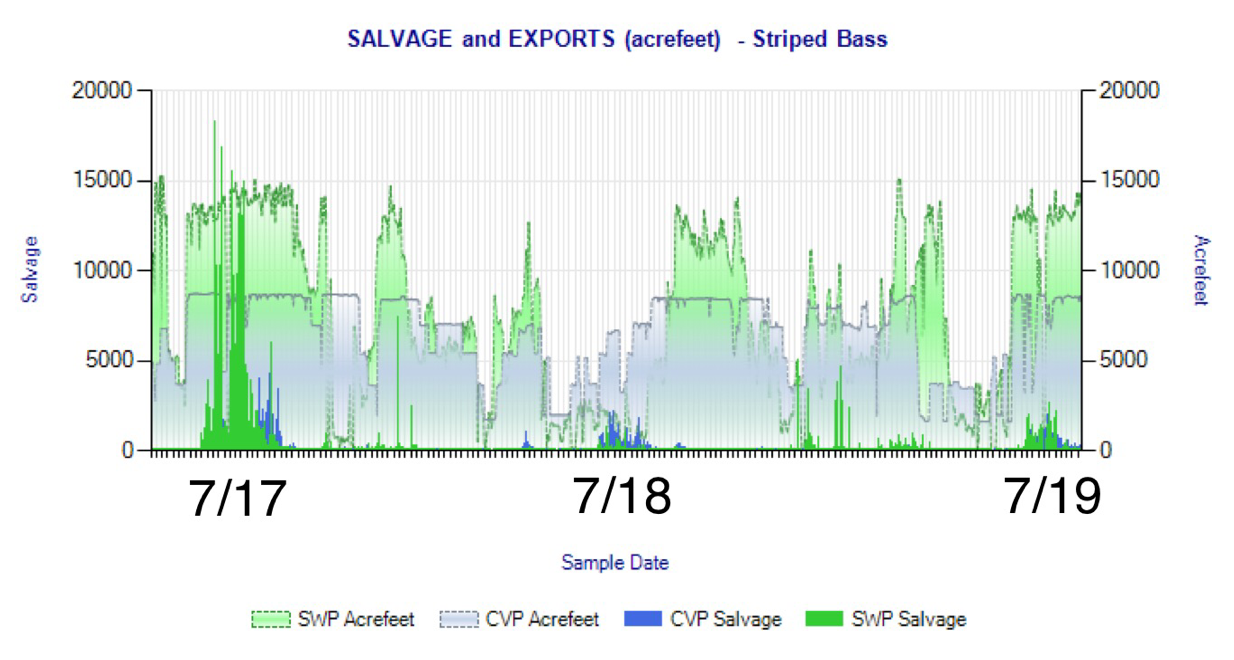

Early indicators for wet year 2019 give me pause and further concern for striped bass recruitment this fall. First, numbers and densities in the 2019 late spring 20-mm survey were way down as compared to 2017. Second, despite high south Delta exports in July 2019, juvenile striped bass salvage is also lower compared to July 2017 (Figure 4), consistent with the lower 20-mm survey results. The summer and fall indices for 2019 will help complete the story.

Figure 1. Striped bass fall index 2000-2018.

Figure 2. Striped bass summer index 1959-2018.

![Figure 3. Striped bass Fall Midwater Trawl Survey Index (log10[index+1]) versus prior Summer Townet Index (log10). Select years labeled, with color of number showing year type: blue=wet, green=normal, and red=critically dry.](http://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/image1-1.png)

Figure 3. Striped bass Fall Midwater Trawl Survey Index (log10[index+1]) versus prior Summer Townet Index (log10). Select years labeled, with color of number showing year type: blue=wet, green=normal, and red=critically dry.

Figure 4. Striped bass salvage at south Delta export facilities with export levels (acre-feet) summer 2017-summer 2019. Note near maximum export levels in July 2017 and 2019.