Dave Vogel and I are contributing a series of posts on the potential effects of the WaterFix Twin Tunnels Project on Delta fishes. Our focus to date has been on salmon. In this post, I focus on the “other” fishes of the Bay-Delta that will be harmed by WaterFix.

Striped Bass (non-native gamefish)

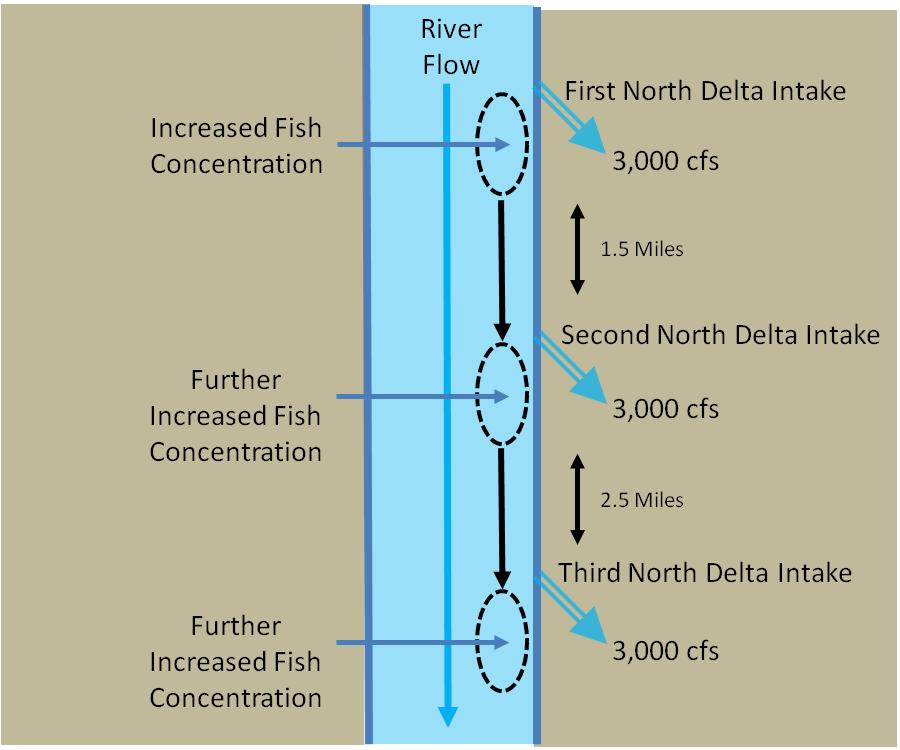

Striped bass will be devastated by WaterFix tunnel intakes located on the lower Sacramento River. The main spawning run of striped bass is in spring in the lower Sacramento River from near Colusa down to the tidal Delta. Eggs and larvae are buoyant and are carried by currents to the tidal Delta and Bay. Nearly all the eggs and larvae must pass the tunnel intakes. The original Peripheral Canal (circa 1980) had a provision to limit diversions during the striped bass spring spawn. The Vernalis Adaptive Management Program (VAMP) from the late 1990s to the late 2000s protected striped bass in spring with higher Delta inflows and reduced exports (generally a limit of 1500 cfs from mid-April to mid-May). The D-1485 Delta standards had a limit on exports through June (6000 cfs). The proposed WaterFix would have spring exports up to 15,000 cfs (9000 from tunnels and 6000 from existing South Delta pumps). Those eggs and larvae that pass the tunnel intakes would be subject to the pull of south Delta exports without the benefit of the extra flow taken at the tunnel intakes.

Longfin Smelt (native)

Longfin smelt will suffer from reduced flows in the winters of drier years. The WaterFix will take a quarter to a third of sporadic uncontrolled winter flow pulses that support the spawn of longfin smelt in drier years. The lower flows will force longfin to spawn further upstream in the Delta where they are vulnerable to central and south Delta exports. The longfin population declines in drier year sequences; the WaterFix will add to downward population pressure.

Delta Smelt (native)

A recent post by Moyle and Hobbs at UC Davis suggests Delta smelt will be better off under WaterFix:

“The status quo is not sustainable; managing the Delta to optimize freshwater exports for agricultural and urban use while minimizing entrainment of delta smelt in diversions has not been an effective policy for either water users or fish.” Comment: So allowing the water projects to take more water will help? Delta inflow and outflow are the key factors in Delta smelt population dynamics – both will be negatively affected by WaterFix.

Moyle and Hobbes point out “reasons to be optimistic about Waterfix,” as follows:

- “Entrainment of smelt into the export pumps in the south Delta should be reduced because intakes for the tunnels would be upstream (of) current habitat for delta smelt and would be screened if smelt should occur there.” Comment: The existing south Delta intakes will continue to take spring-summer water (and smelt) from the Delta in similar amounts as in the past. However, smelt in the south Delta will not have the benefit of the inflow taken by the proposed tunnels. Smelt will also be more likely to spawn near or upstream of the tunnel intakes. Screens on the tunnel intakes would not help save larval smelt and would be minimally effective for adult smelt.

- “Flows should be managed to reduce the North-South cross-Delta movement of water to create a more East-West estuarine-like gradient of habitat, especially in the north Delta.” Comment: If outflow remains low or becomes even lower, the low salinity zone will more frequently move further into the Delta. The north Delta already has a strong gradient – allowing the gradient to move further upstream into the Delta will have adverse effects. Circulation in the south Delta will remain poor, and the south Delta will continue to experience reverse flows, because south Delta exports will continue. The south Delta will lose the benefit of inflow taken by the tunnels.

- “Large investments should be made in habitat restoration projects (EcoRestore) to benefit native fishes, including delta smelt.” Comment: Delta smelt are totally dependent on pelagic (open-water) habitats, but few EcoRestore projects will improve such habitats. Salinity, water temperature, turbidity, tidal-flow dynamics, water quality, and nutrients are by far the most important factors controlling smelt population dynamics.

Steelhead (native)

Steelhead, much like salmon, are affected by ancillary changes in reservoir storage and releases, river flows, Delta inflow and outflow, water temperatures, and turbidities. But the greatest threat to steelhead, as for salmon, is from the three large intakes and their screen systems, which will adversely affect young steelhead passing on their way to the ocean.

Splittail (native)

Splittail were once on the endangered species list. Today, splittail numbers, especially for recruitment of juveniles, are way down, well below the numbers occurring at the time of their listing. Splittail from the Bay-Delta migrate upstream into river floodplains upstream of the Delta to spawn in spring. The three largest floodplain areas are in the Yolo Bypass, Sutter Bypass, and the lower San Joaquin River wildlife areas. The Sutter group will be at high risk to fry-stage entrainment/impingement at the tunnel intakes. The San Joaquin group will have a continued risk to south Delta exports, a risk made worse by the diversion of inflow from the Sacramento River into the tunnels.

American shad (non-native gamefish)

American shad migrate from the ocean to Valley rivers to spawn in the spring. Eggs, larvae, and fry from the major spawning rivers of the Sacramento Valley must pass the tunnel intakes in the north Delta. Like the striped bass, these lifestages of American shad will be devastated by entrainment and impingement at the tunnel intakes.

Pacific Lamprey

Like salmon and steelhead, Pacific lamprey migrate from the ocean to spawn in Valley rivers during the spring. Young larval lamprey would pass the tunnel intakes on their migration back to the ocean. Because they are weak swimmers they would be highly vulnerable to impingement or predation at the screens.

Native Minnows and Suckers

Many species of native minnows and suckers migrate upstream from the Delta to Valley rivers to spawn in spring and summer. Their young must pass the tunnel intakes on their return to the Delta, and thus will be at risk to entrainment/impingement at the tunnel screens.

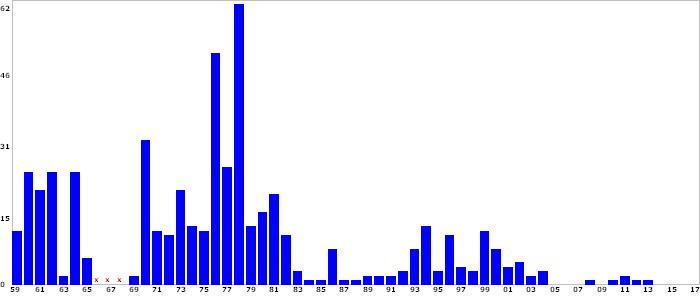

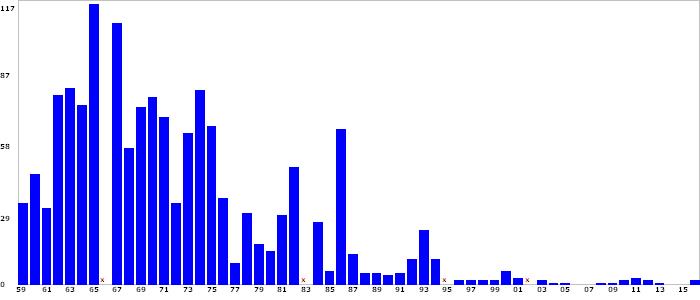

The Delta smelt Summer Townet Index is at record low numbers in recent years including the wet year 2017 index.

The striped bass Summer Townet Index remains near record low in 2017.