A suite of disturbances in the Central Valley has eroded many of the inherent characteristics that once conferred resilience in historically abundant salmon populations. Resilience is provided by natural abundance, diverse run timing, multiple habitats, and broad habitat availability and connectivity. Last November, I recommended a dozen specific actions to save winter-run salmon. This post focuses on long-term actions to restore resilience in Central Valley salmon populations and fisheries.

Resilience has declined due to the narrowing of optimal adult migration conditions, the confinement of spawning to localized areas and time periods, the limitation of outmigration periods and regional conditions, the confinement of rearing periods, and the amount of and connectivity of geographical habitats.

Confinement of salmon below dams constructed in the 1940’s took away much of the resilience in the salmon populations. In the past 70 years, the populations have depended upon a narrowing range of habitat conditions in time and space in the limited spawning habitat below Shasta and other major rim dams, as well as in the migration and rearing habitat between these spawning areas and San Francisco Bay. The development of the State Water Project further diminished Central Valley salmon’s remaining resilience.

Resilience has been lost in following ways:

- Spawning habitat has gradually declined below dams due to lack of new gravel recruitment and the gradual armoring of spawning riffles.

- Spawning habitat has declined with weakened management of water temperature below Shasta, narrowing the spawning reach from 40 miles to as little as 10 miles. Early spawning of winter-run salmon in April and May has been lost even in wetter years like 2016 because of flow reductions in these months and because the temperature of water released from Shasta in these months has been increased.

- Embryo survival in redds and fry survival in rearing reaches has been compromised by low, warm summer and fall flows. More redds are dewatered with more frequency as water deliveries for irrigation taper off in the fall.

- Winter flows that carry juveniles to and through the Delta are lower and more sporadic. Fall and early winter flows and pulses that occurred historically and enhance smolt emigration no longer occur to the extent they once did, particularly in the spawning reaches immediately below the major reservoirs that regulate all the inflow.

- With lower and warmer river and Delta flows, salmon predators have become increasingly more effective.

- The quality of the physical habitat of salmon, and winter-run salmon in particular, has been adversely modified over time.

Hatcheries can reduce resilience over time if specific precautions are not taken to avoid weakening the gene pool and population diversity, and to avoid interactions with wild fish. But hatcheries can also be used to strengthen resilience by increasing genetic diversity and spreading populations in time and geographical range.

Habitat restoration can increase resilience by limiting bottlenecks such as lack of spawning gravels or migration corridor connectivity. Flow and water temperature remain the two most important habitat factors in the Central Valley. The availability of floodplain rearing habitat is also important. Reduced winter flooding resulting from global warming and lower reservoir carryover storage levels has reduced habitat resilience over time. The gradual decline of large wood in Valley rivers over the decades has reduced the rearing capacity of streams and rivers. River and stream channels have gradually degraded due to scour and the lack of large wood and natural sediment supplies.

A resilience-based approach is likely to be more successful than traditional mitigation or restoration approaches “by seeking to rebuild suites of disturbance-resistant characteristics” that were historically present in the Central Valley. A resilience-based strategy “emphasizes the diversification of life history portfolios” and “would seek to maintain a diversity of habitat types, including less productive habitats that may have primary importance only as refugia or alternate spawning habitat during disturbances.” The ultimate goal is to get salmon smolts to San Francisco Bay and the ocean, which offer cold waters and abundant food.

Historically, resilience occurred at all life stages, beginning with an abundance of adults. With the present depressed adult runs, resilience is thus already handicapped. Building runs requires restoring resilience of all life stages, starting with egg survival. Turning around the decades of decline in resilience and increasing it, especially in the short term to avoid extinctions, is a therefore a major, expensive undertaking. First, we should focus on stopping further declines in resilience. Second, we should improve resilience where we can to begin the healing. The following are some suggestions:

- Increase the salmon spawning reach below Shasta in time and space by providing better flows and water temperatures. Extend the spawning reach back down to Red Bluff and diversify timing with better early season conditions (e.g., April-May winter run spawning). Improve physical habitat further downstream toward Red Bluff, not just near Redding. Extend habitat improvements where possible into tributaries (e.g., Clear and Battle Creeks).

- Extend the range of salmon into former habitats, such as the planned improvements on Clear and Battle creeks, and in the reaches above selected rim dams.

- Expand the conservation hatchery program to diversify genetics and support expanded range. Select for specific natural genetic traits that have been lost or changed to increase diversity.

- Develop and implement a river flow management plan for the Sacramento River downstream of Shasta and Keswick dams that considers the effects of climate change and balances beneficial uses with the flow and water temperature.

- Increase the range in time and space of rearing and migratory habitats that accommodate diversity.

- Develop and implement a long-term large wood and gravel augmentation plan consistent with existing plans and flood management to increase and maintain spawning habitat for salmon and steelhead downstream of dams. Diversify habitats and reduce habitat bottlenecks. Expand rare and important habitat types.

- Counteract where possible the effects of climate change. Where changes in flow and water temperature changes delay smolting, make changes that return diversity.

- Provide a more natural diversity of flow pulses immediately below major dams during the emigration season (i.e., December-April) to diversify the timing and life stages of the emigration of juvenile salmon.

A final note:

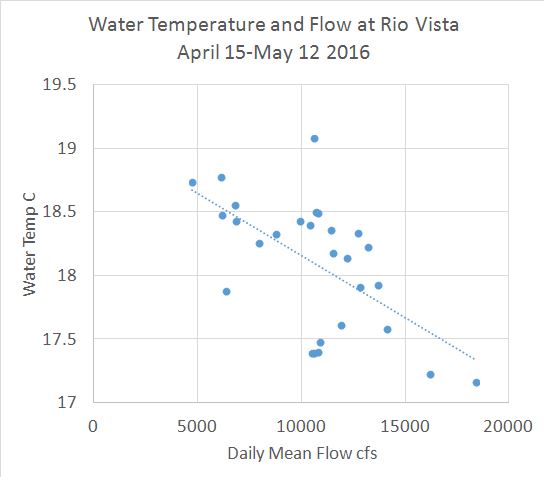

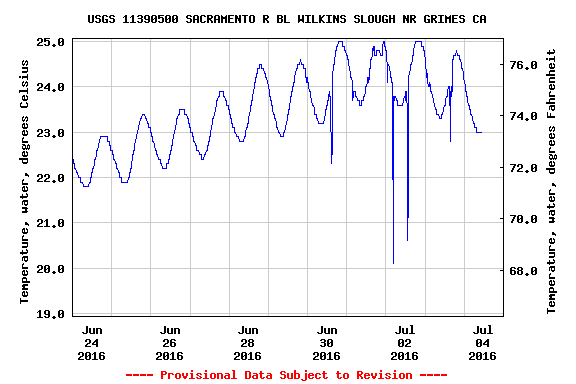

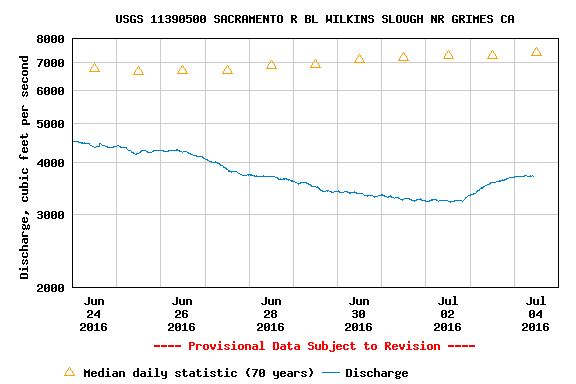

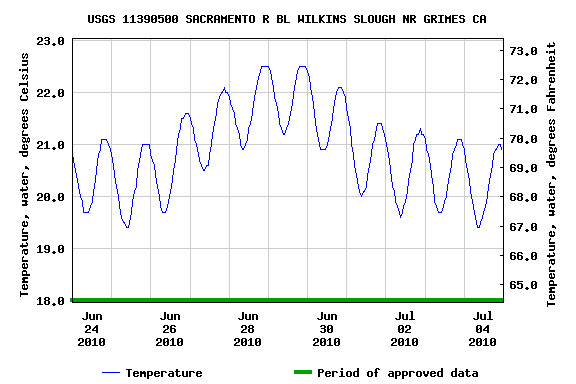

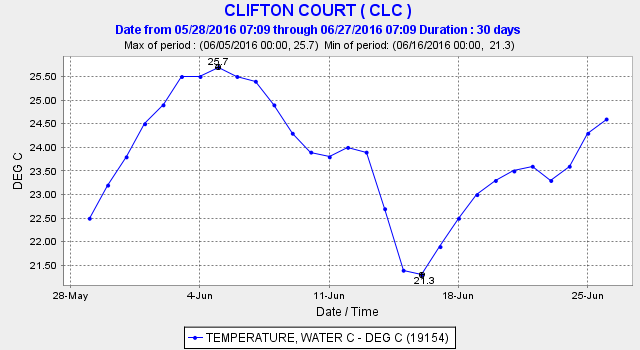

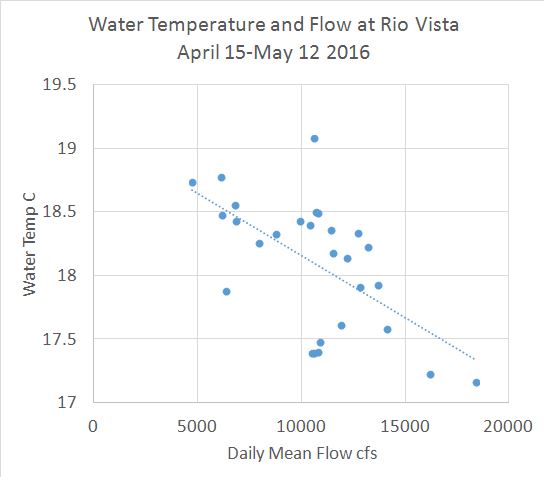

Instead of improving resilience, the Delta “WaterFix” will only cut further into and adversely modify the resilience of the salmon populations. There will be more demands on Shasta storage to meet new Tunnel diversion capacity. Flows below the Tunnel intakes will be lower, further reducing resilience by warming through-Delta spring migration routes (Figure 1). Less freshwater flow into the Delta will further alter Delta habitats and make them more conducive to non-native invasive species of plants and animals. Delta habitat will be warmer earlier in the season, less turbid, and more brackish.

Figure 1. Water temperature versus mean daily flow at Rio Vista in spring 2016. (Source of data: CDEC). Resilience in terms of Delta migration survival would be reduced by the effects of the proposed WaterFix on water temperature in the Delta spring migration route.