The State Water Project (SWP) is not protecting salmon in the Feather River. The Feather River’s once-prolific populations of wild spring-run and fall-run salmon have been replaced by smaller numbers of hatchery fish of inferior genetic composition.

The fact that the replacement of wild fish by hatchery fish plagues all salmon stocks in the Central Valley Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) is no excuse. The California Department of Water Resources (DWR) has many responsibilities and commitments to protect Feather River salmon under the SWP’s project’s hydropower license, water rights, and other permits, and more generally under the public trust doctrine and the reasonable use doctrine in the state constitution (Article X, Section 2). The SWP has not met these responsibilities or related commitments since the SWP’s completion in the 1960s.

Neither Feather River nor Central Valley salmon recovery can be achieved without cleaning up the mess in the lower Feather River. This fact is recognized widely in salmon recovery plans, federal biological opinions, State incidental take permits, and even in part in the Oroville Settlement Agreement for the relicensing of the SWP’s hydroelectric facilities at Oroville. DWR has made many promises and commitments toward salmon recovery, but has realized very few. While DWR has spent billions on upgrading project infrastructure, especially after the 2017 spillway failure, it has spent little toward salmon recovery.

So how should DWR focus its salmon recovery process for the Feather River at this point?

Well, most certainly on mandatory provisions in the soon-to-be issued FERC hydropower license and related State Board water quality certification. Also, on existing or needed conditions in its water right permits that extend beyond the small geographic scope of the FERC license. The next focus should be on the “Habitat Expansion Agreement for Central Valley Spring-Run Chinook Salmon and California Central Valley Steelhead” (HEA) that DWR and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) agreed to during the Oroville relicensing. There are also requirements in the Reasonable and Prudent Measures in the 2016 federal biological opinion for the Oroville relicensing.

The overall focus should be on recommendations in specific salmon recovery plans pertaining to the project.

Below are my recommendations for top priority actions for Feather River salmon recovery from among the sources mentioned above.

Spring-Run and Fall-Run Salmon Introgression

A primary focus and priority should be on minimizing introgression of the spring-run and fall-run salmon populations in the hatchery and natural spawning area of the 8-mile Low Flow Channel (LFC) downstream of Oroville Dam.

For the natural spawning area of the LFC, one option is a segregation weir at the lower end above the Thermalito Afterbay outlet that would provide for selective passage of selected adult spawners into the spawning area. Similar weir systems are operated in lower Battle Creek and lower Butte Creek. For example, the weir could provide seasonal passage to accommodate only spring-run spawners that arrive earlier than fall-run. The fall-run would be forced to spawn downstream of the afterbay outlet in the High Flow Channel (HFC) where habitat conditions, especially water temperatures, would be more suitable later in the year when fall-run salmon are spawning. The weir could also trap fish to allow direct segregation or egg taking, or trapping-and-hauling of selected adults or offspring produced in the LFC.

The hatchery program should focus on broodstock selection and hatchery operations that produce returning adult spring-run and fall-run salmon of the highest genetic integrity possible. It should also operate to limit straying of Feather River origin hatchery salmon. Hatchery operations should also focus on strategies for smolt releases that provide the greatest return while limiting effects on wild salmon. Otherwise, the Feather River Fish Hatchery Improvement Program (Article A107 of the Oroville Settlement Agreement) should be implemented. This program sets specific targets for hatchery temperatures, requires development of a hatchery management program (including a Hatchery and Genetics Management Plan), potential installation of a water supply disinfection system, and funding for annual hatchery operations and maintenance.

Lower Feather River Habitat Improvements

There are many potential habitat improvements in the LFC and in the High Flow Channel (HFC, the lower Feather River downstream of the outlet of Thermalito Afterbay). Habitat improvements could provide significant benefits to adult salmon holding and spawning success, and wild fry survival and smolt production. One general category is water quality (i.e., water temperature) and streamflow management through improved infrastructure and operations strategies of flow releases to the LFC and HFC. The second category is improvements to the physical (non-flow) habitat features, including channel configuration (depths, velocities, and substrate composition) in both the LFC and HFC.

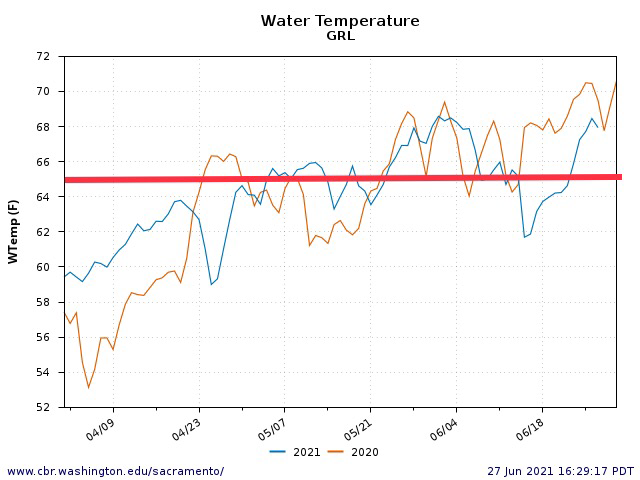

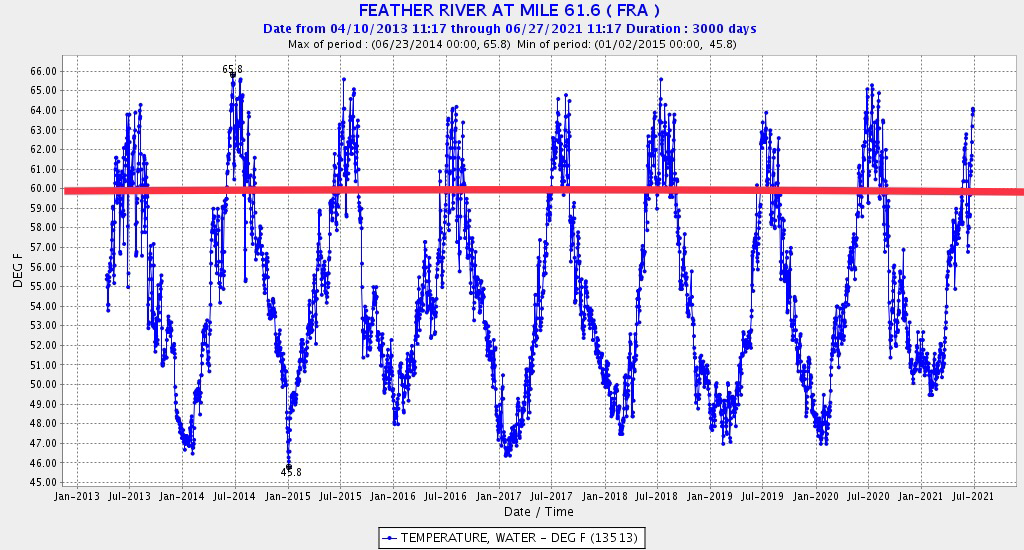

Flow and Water Temperature

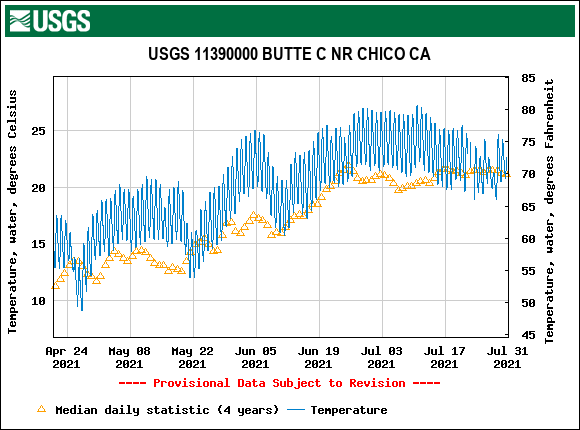

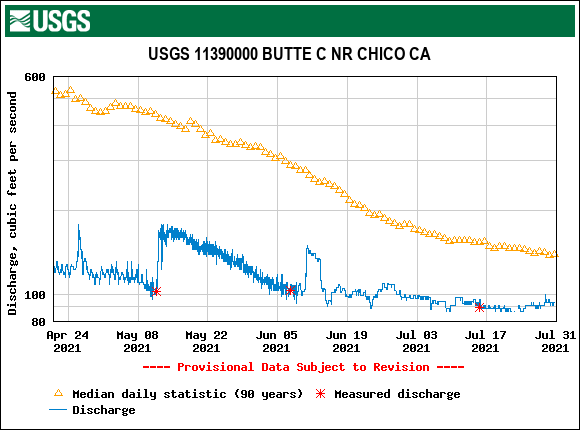

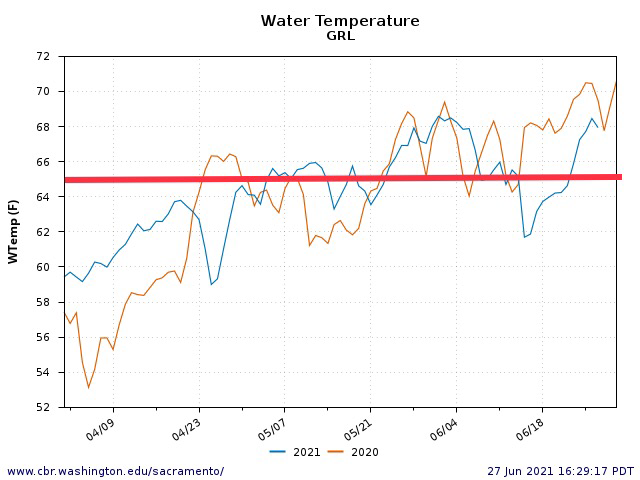

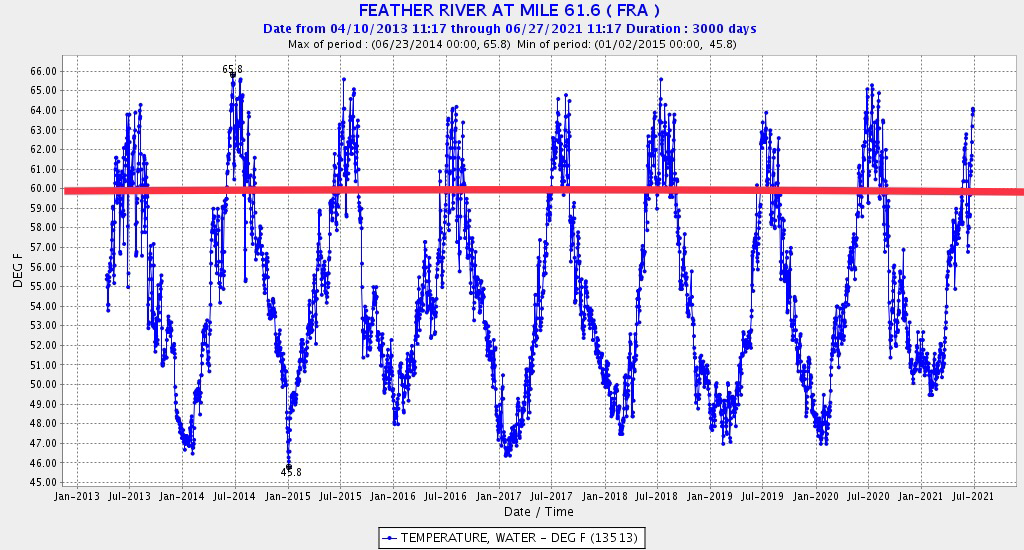

Adult spring-run salmon migrate in spring to the lower Feather River, then hold in deep pools over the summer to spawn in early fall. Adequate flows and cool water temperatures are essential elements of (1) spring adult migration habitat in the lower Feather River and (2) over-summering holding habitat. Without adequate flows for migration and holding, adult salmon are prone to disease and pre-spawn mortality, poor reproductive success, or lower survival of eggs. Water temperatures should be no higher than 65oF during migration and 60oF during holding to minimize such detrimental effects. Water temperatures in the HFC (or LFC) should not exceed 65oF in spring (Figure 1). Water temperatures in the LFC should not exceed 60oF in summer (Figure 2). The various planning documents outline potential options to reduce water temperatures in the LFC and HFC. These include measures to sustain Oroville Reservoir’s cold-water pool and reliably release water from it. They also include measures to keep water in the Afterbay complex cooler prior to release into the HFC. Still other measures may include limiting release of water from the Afterbay through a variety of modifications to facilities and operations.

Physical Habitat Features

The Biological Opinion and Settlement Agreement for the Oroville relicensing include prescriptions for the restoration and enhancement of lower Feather River salmon habitat, consistent with the NMFS Salmon Recovery Plan:

- Design and build infrastructure and stream channel features that will allow for segregation and reproductive isolation between fall-run and spring-run Chinook salmon naturally spawning in the LFC of the Feather River.

- Develop a spawning gravel budget and introduction plan, and implement the plan.

- Design, construct, and maintain side-channel and off-channel habitats for spawning and rearing salmon and steelhead.

- Obtain river riparian and floodplain habitat through easements and/or land acquisition as needed, allowing the river room to grow and move as necessary to provide key transition habitats, and to minimize degradation (such as channel incisions/filling and substrate armoring) of existing high quality habitat features. Provide a balance between the needs of flood conveyance, recreation, and aquatic, riparian and floodplain habitat in and near an urban environment.

- Design, build, and maintain channel features that provide optimum habitat, fish passage, and flood control necessary to minimize scour and erosion. High-flow floodplain channels may be such a feature.

- Provide deeper holding habitat and cover for adult over-summering spring-run salmon in the channel habitat features described above. Such habitat is often larger pools with a large bubble curtain at the head, underwater rocky ledges, and shade cover throughout the day. Adult spring-run Chinook salmon may also seek cover in smaller “pocket” water behind large rocks in fast water runs.

Benefits to Other Species

Efforts to improve salmon habitat in the lower Feather River will benefit other important native fish.

The lower Feather River is home to other significant fisheries resources including the following:

- Spawning anadromous steelhead – spawning is concentrated in Low Flow Channel below the Fish Barrier Dam in winter and spring.

- Steelhead eggs in gravel redds are concentrated in Low Flow Channel below the Fish Barrier Dam in winter and spring.

- Steelhead yearling smolts rearing occurs in the Low Flow Channel and the High Flow Channel in winter and spring.

- Steelhead fry rearing occurs in the Low Flow Channel and the High Flow Channel in winter and spring.

- Spawning of green and white sturgeon occurs in spring in the High Flow Channel.

- Sturgeon eggs are found in rock crevices of the river bottom in the High Flow Channel in spring.

- The newly hatched larvae and fry of sturgeon occur on the river bottom in the High Flow Channel in spring.

- Resident trout and non-salmonid fish occur year-round throughout the lower Feather River.

Habitat Expansion Agreement – Final Habitat Expansion Plan

The Oroville Project Habitat Expansion Agreement (HEA) requires creation of habitat suitable to increase populations of Central Valley spring-run Chinook salmon by a minimum of 2000 adults. The Habitat Expansion Plan proposed by DWR and Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) focuses on physical habitat improvements to the Lower Yuba River to benefit spring-run Chinook salmon. According to DWR and PG&E, this would develop a viable, self-sustaining population of spring-run Chinook salmon below Englebright Dam.

In my opinion, this is a big mistake. The lower Yuba River below Englebright Dam has many of the same problems as the lower Feather. Its spawning habitat already has capacity for many more spring-run salmon than are currently utilizing it.

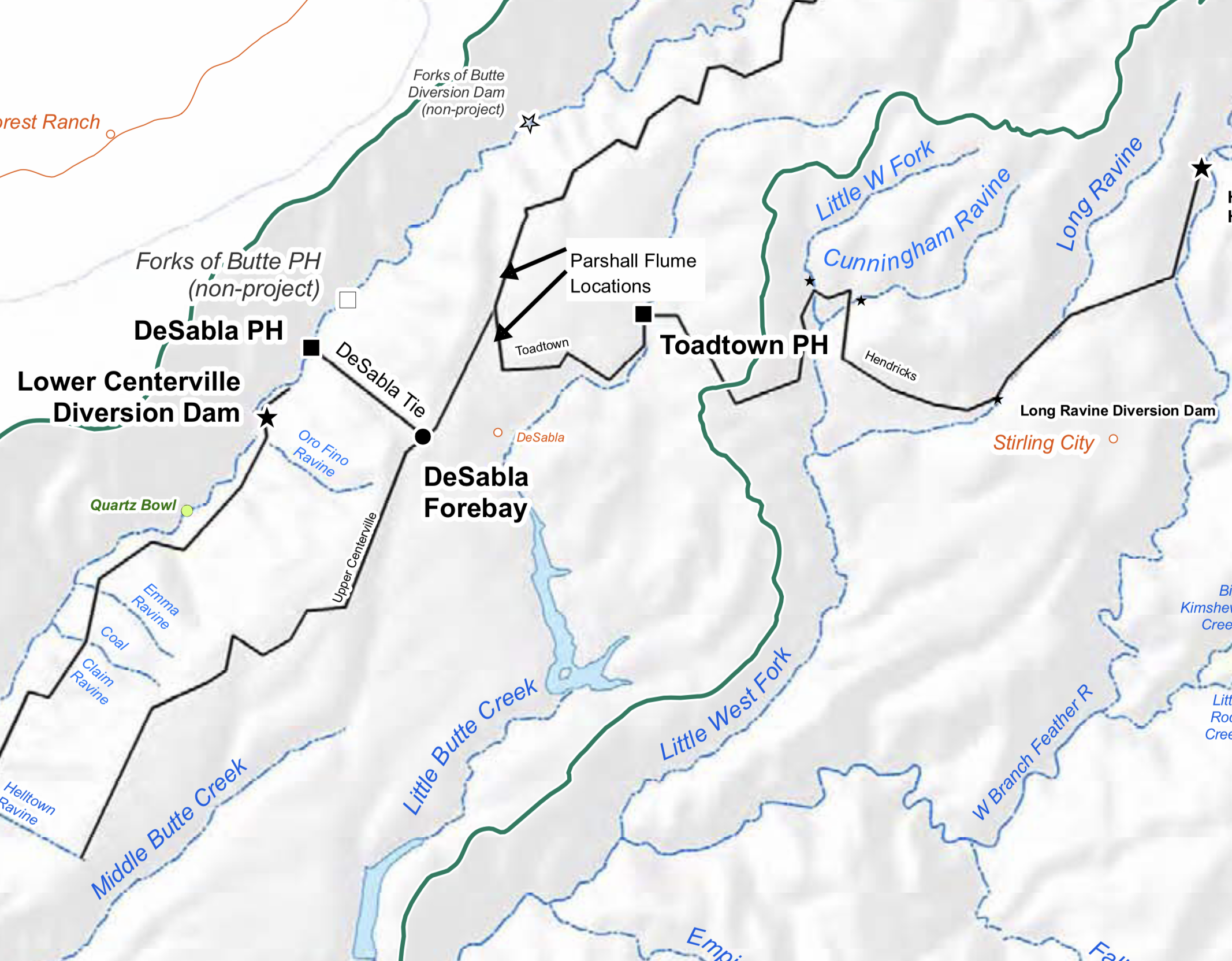

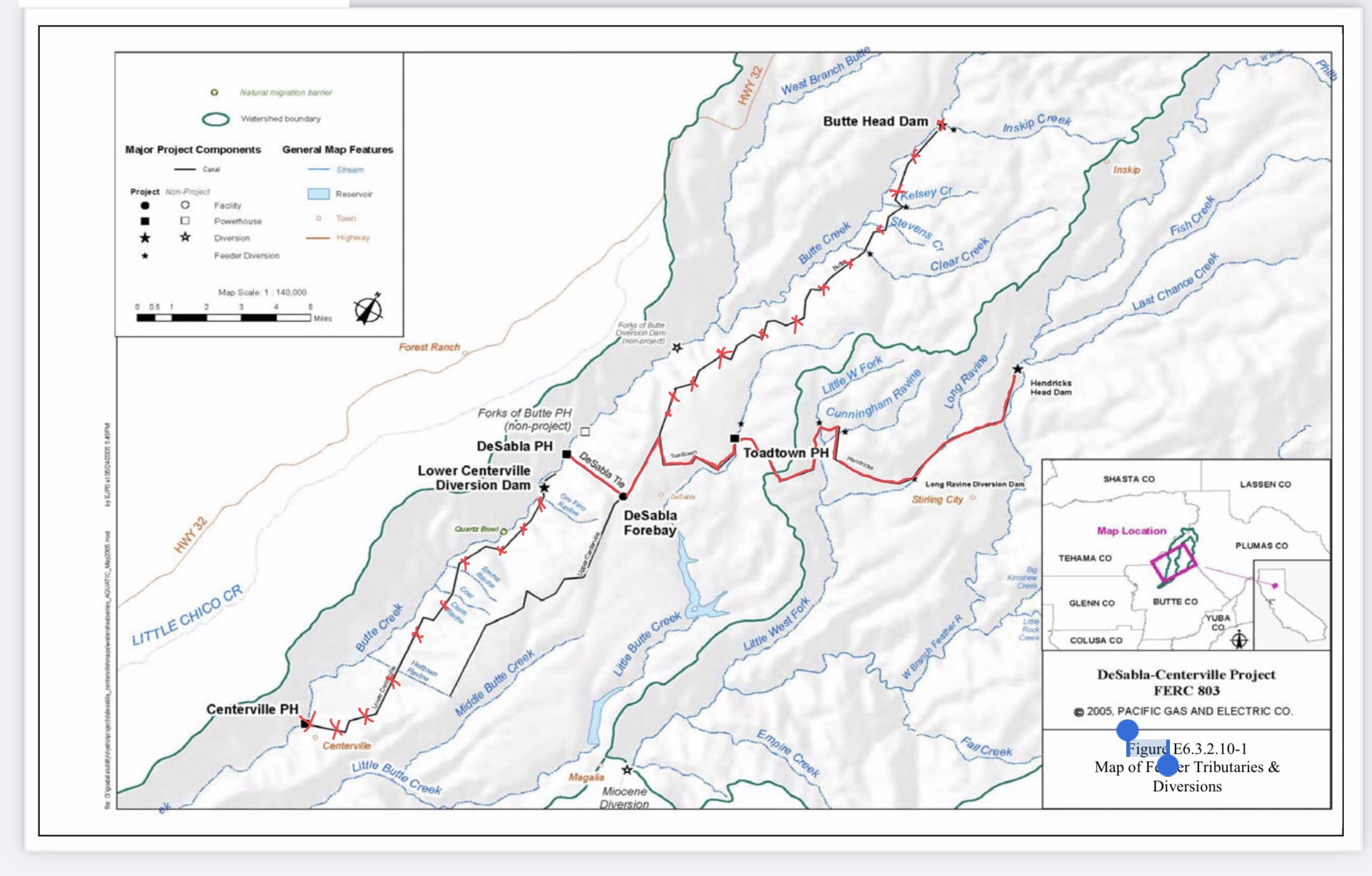

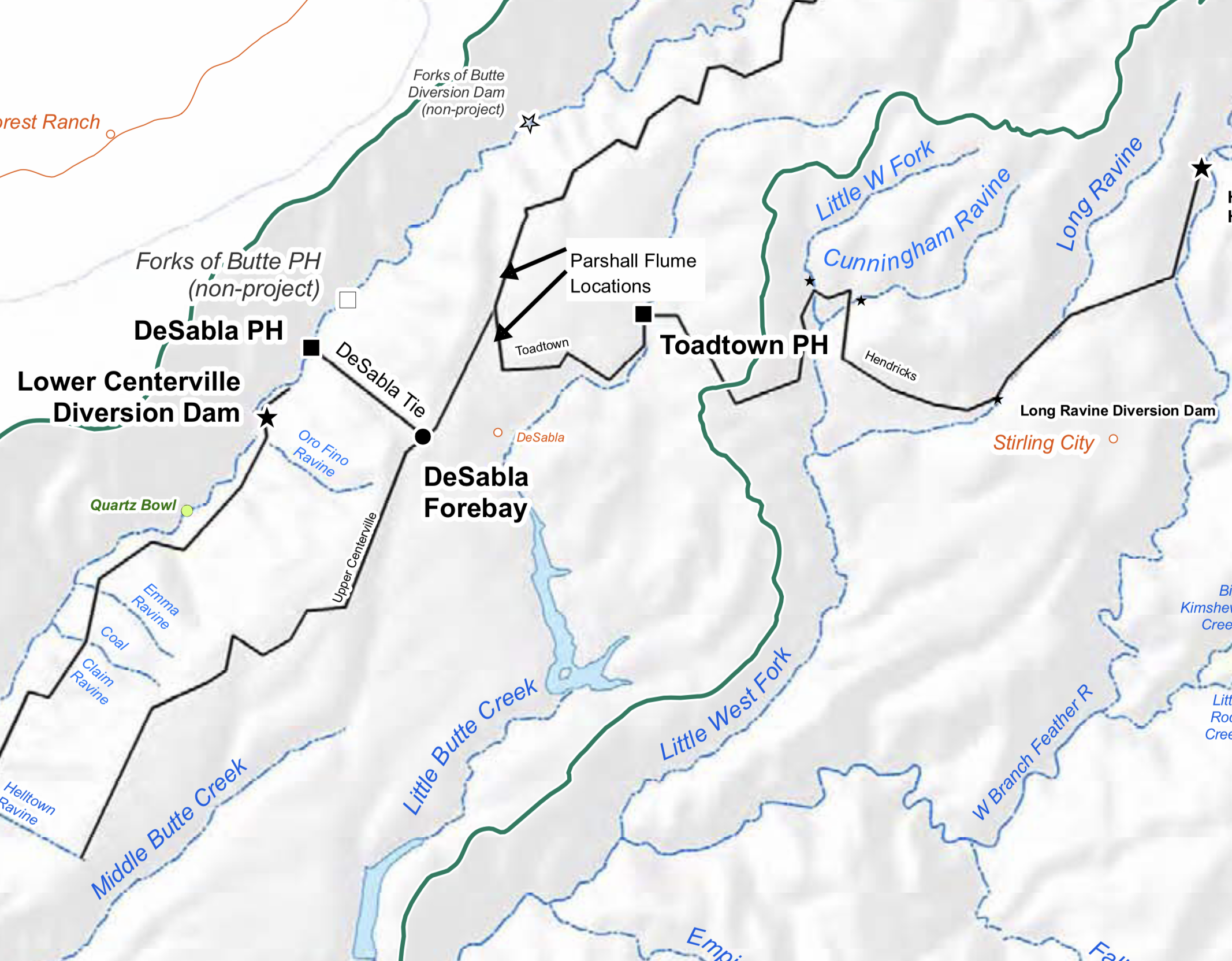

A much better option is saving the Butte Creek spring-run salmon, the largest core population of the CV Spring Run Salmon ESU. A first phase of a Butte Creek recovery program would be to secure Butte Creek’s supply of cold Feather River water for the immediate future. PG&Es decommissioning of the DeSabla-Centerville Hydroelectric Project would potentially eliminate or reduce cold-water inputs from the West Branch of the Feather River to Butte Creek. The DeSabla Project moves water from the West Branch Feather in canals for release into Butte Creek through the DeSabla Powerhouse. This additional, relatively cool water provides holding and spawning habitat that presently sustains Butte Creek’s spring-run salmon and supports Butte Creek’s fall-run salmon and steelhead.

A second phase of a Butte Creek recovery program would entail removal of the Lower Centerville Diversion Dam, a low-head dam on Butte Creek just downstream of the DeSabla powerhouse (Figure 3). Since 2014, this dam has not diverted any water. Removal of the dam and diversion, and potentially removal or modification of other fish passage improvements at natural barriers if needed, could allow access to many miles of upstream spawning and rearing habitat on Butte Creek. This would truly expand spring-run habitat in the Central Valley.

Summary and Conclusion

Feather River salmon recovery should proceed through improvements in flow, water quality, and physical habitat, project operations and facilities, and hatchery operations and facilities. Habitat expansion for spring-run salmon should focus on saving the existing run of spring-run salmon on Butte Creek and expanding their upstream range, not on physical improvements to the lower Yuba River.

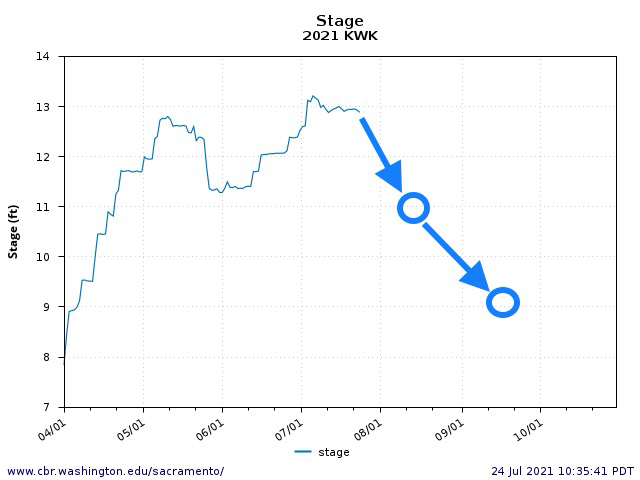

Figure 1. Water temperature in the lower Feather River within the HFC in spring 2020 and 2021. Red line is upper water temperature safe limit for migrating salmon.

Figure 2. Water temperature in the lower Feather River within the LFC, 2013 and 2021. Red line is upper water temperature safe limit for pre-spawn, adult holding salmon.

Figure 3. Map of PG&E DeSabla Hydroelectric Project features on Butte Creek and the West Branch of the Feather River.

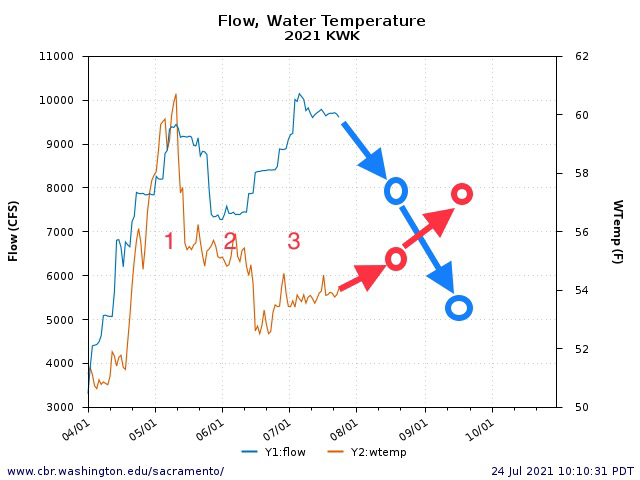

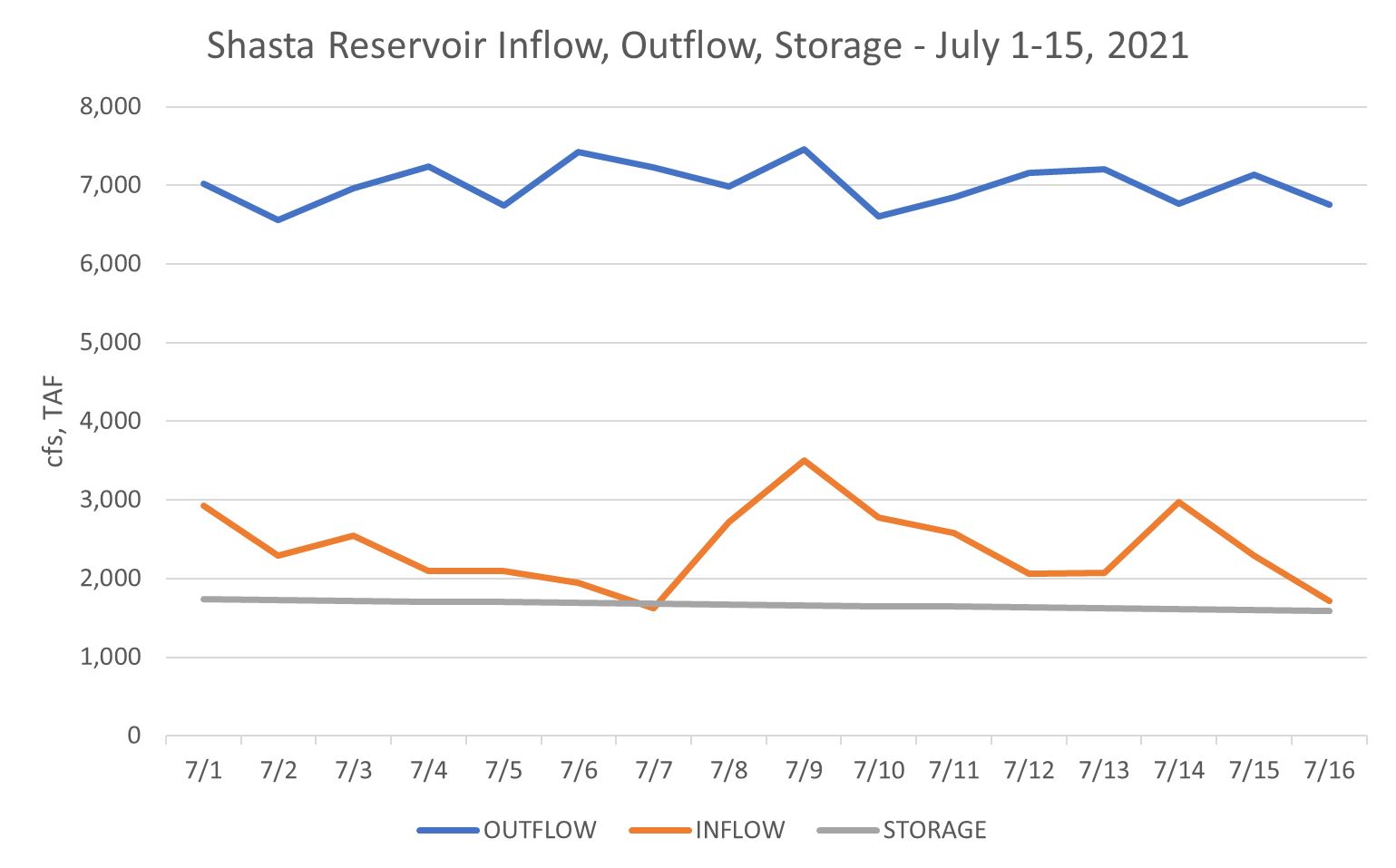

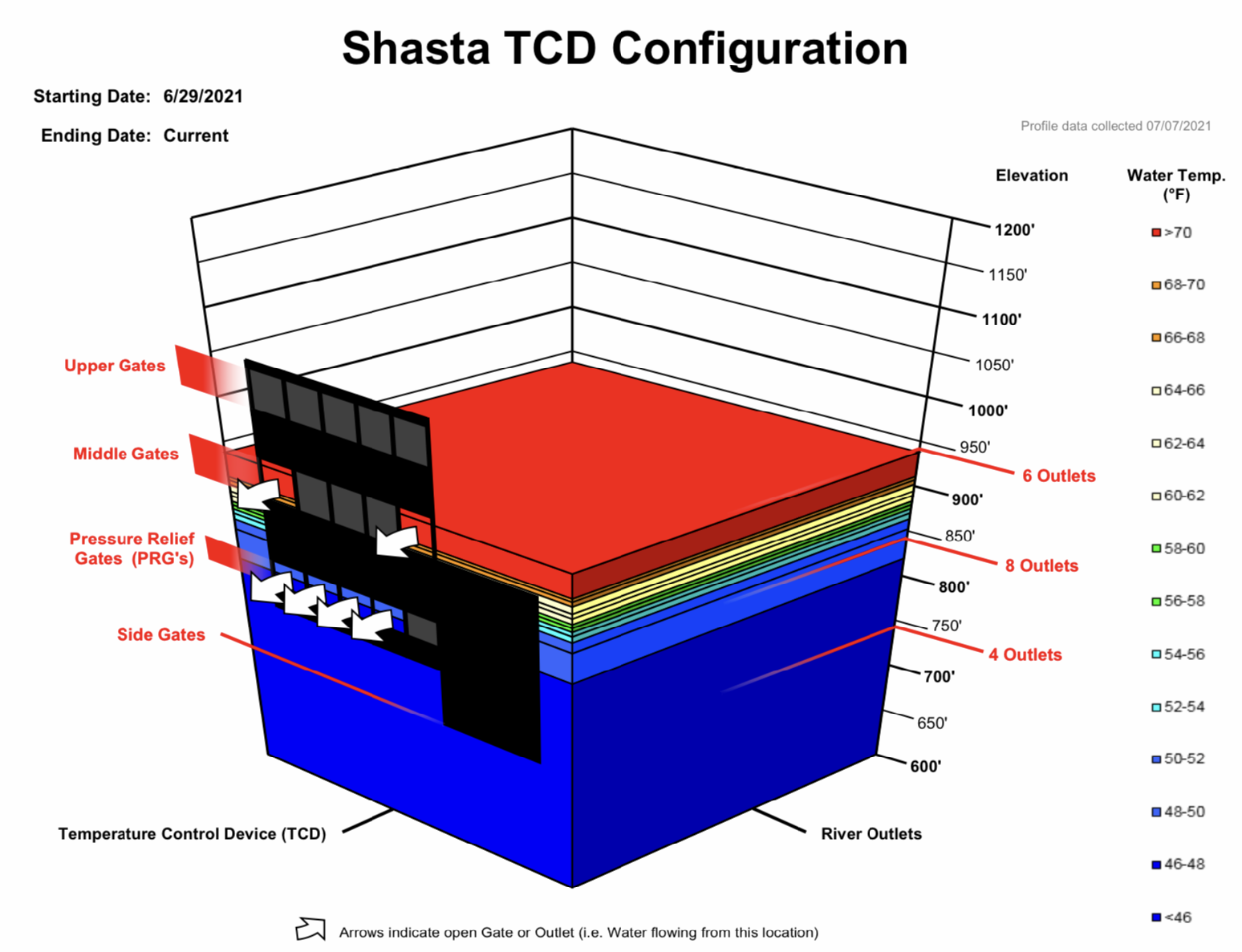

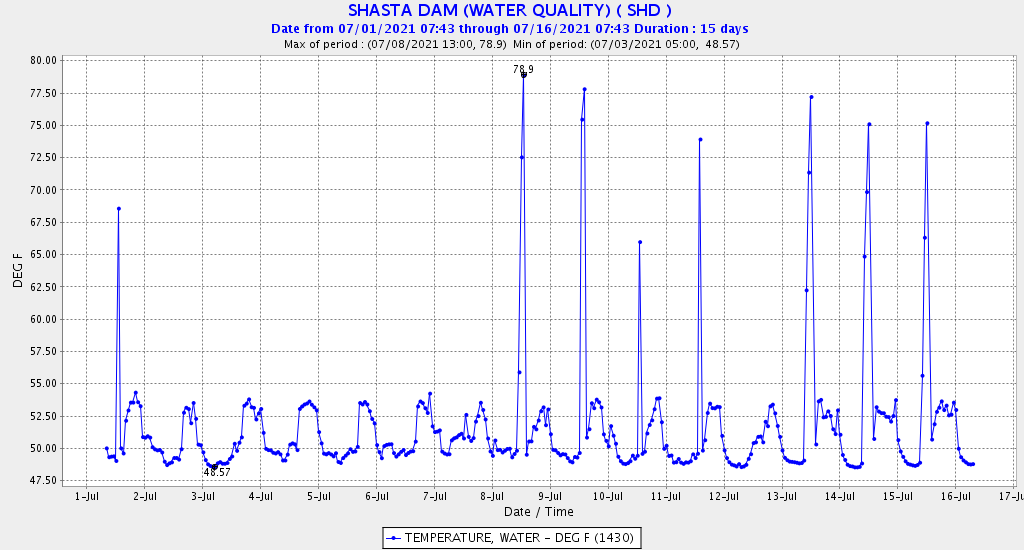

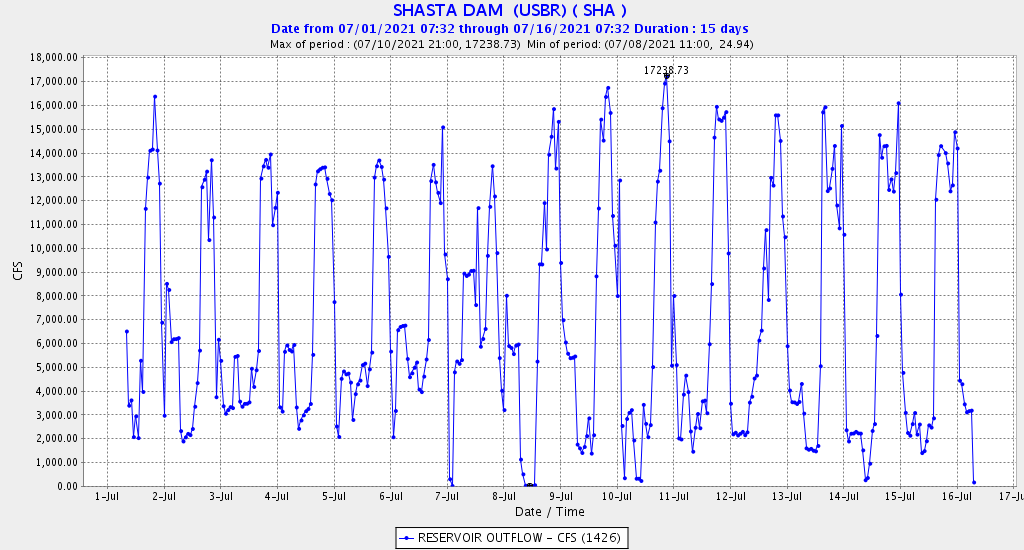

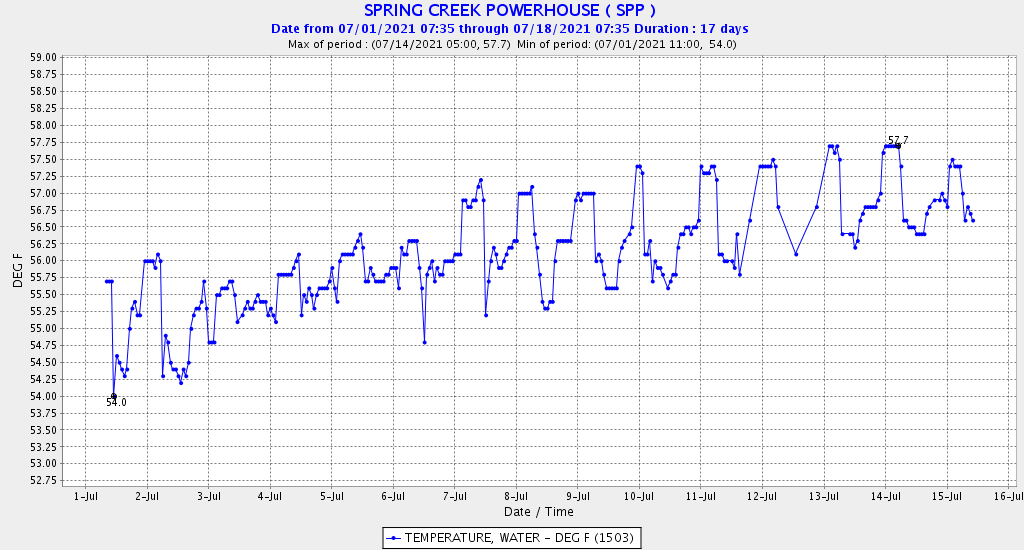

Figure 3a and 3b. Hourly water temperature (a) and flow (b) release pattern from Shasta Dam during first half of July 2021. Note most peaking-power releases are in afternoon and evening hours, with water temperatures several degrees higher during the daily peak generation. Daily average releases were 6500-7500 cfs, with peaks on the 6th and 9th.

Figure 3a and 3b. Hourly water temperature (a) and flow (b) release pattern from Shasta Dam during first half of July 2021. Note most peaking-power releases are in afternoon and evening hours, with water temperatures several degrees higher during the daily peak generation. Daily average releases were 6500-7500 cfs, with peaks on the 6th and 9th.

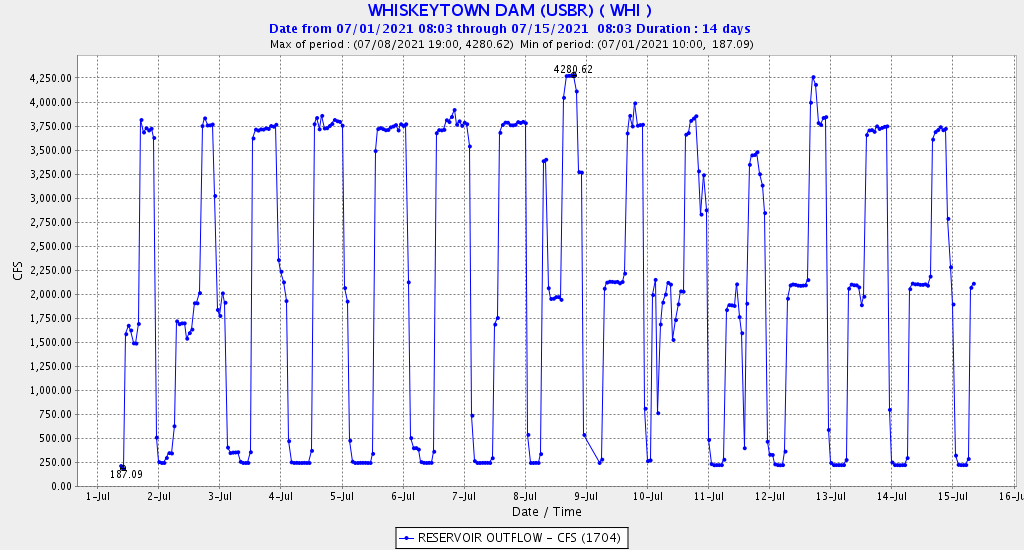

Figures 4a and 4b. Hourly water temperature (a) and flow (b) release pattern from Whiskeytown Dam during first half of July 2021. Note most peaking-power releases are in afternoon and evening hours, with water temperatures in the middle range of the daily pattern or about 1ºF below the daily maximum. Note the base flow of 250 cfs is to Clear Creek, with the remainder to Spring Creek powerhouse on Keswick Reservoir. Also, note peak releases to the Spring Creek powerhouse were about 3500 cfs for 12 hours from July 3-8. Daily average releases rose from about 1000 cfs on July 1 to 2000 cfs on July 4, then dropped to 1500 cfs on July 11, only to increase again through July 15.

Figures 4a and 4b. Hourly water temperature (a) and flow (b) release pattern from Whiskeytown Dam during first half of July 2021. Note most peaking-power releases are in afternoon and evening hours, with water temperatures in the middle range of the daily pattern or about 1ºF below the daily maximum. Note the base flow of 250 cfs is to Clear Creek, with the remainder to Spring Creek powerhouse on Keswick Reservoir. Also, note peak releases to the Spring Creek powerhouse were about 3500 cfs for 12 hours from July 3-8. Daily average releases rose from about 1000 cfs on July 1 to 2000 cfs on July 4, then dropped to 1500 cfs on July 11, only to increase again through July 15.