In a May 29 post, I discussed how a small diversion of cold water from the West Branch of the Feather River sustains the Butte Creek spring-run Chinook salmon, the largest spring-run salmon population in the Central Valley. In a May 8 post, I described how the Shasta River, despite its relatively small size, produces up to half the wild fall-run Chinook salmon of the Klamath River. In both examples, it is not the amount of water, but the quality of the water and the river habitat that matters. In the former case, man brought water to the fish. In the latter, man returned water and habitat to the fish.

While both examples are remarkable given the relatively small amount of water involved, the relatively small restoration effort required on the Shasta River and the minimal effect on agricultural water supply make it almost unique.

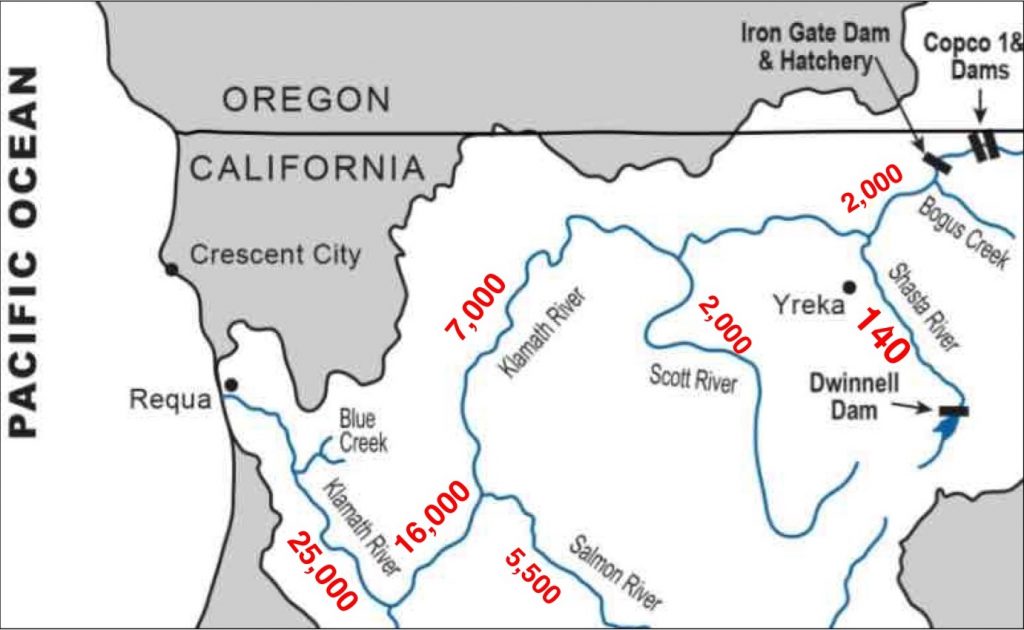

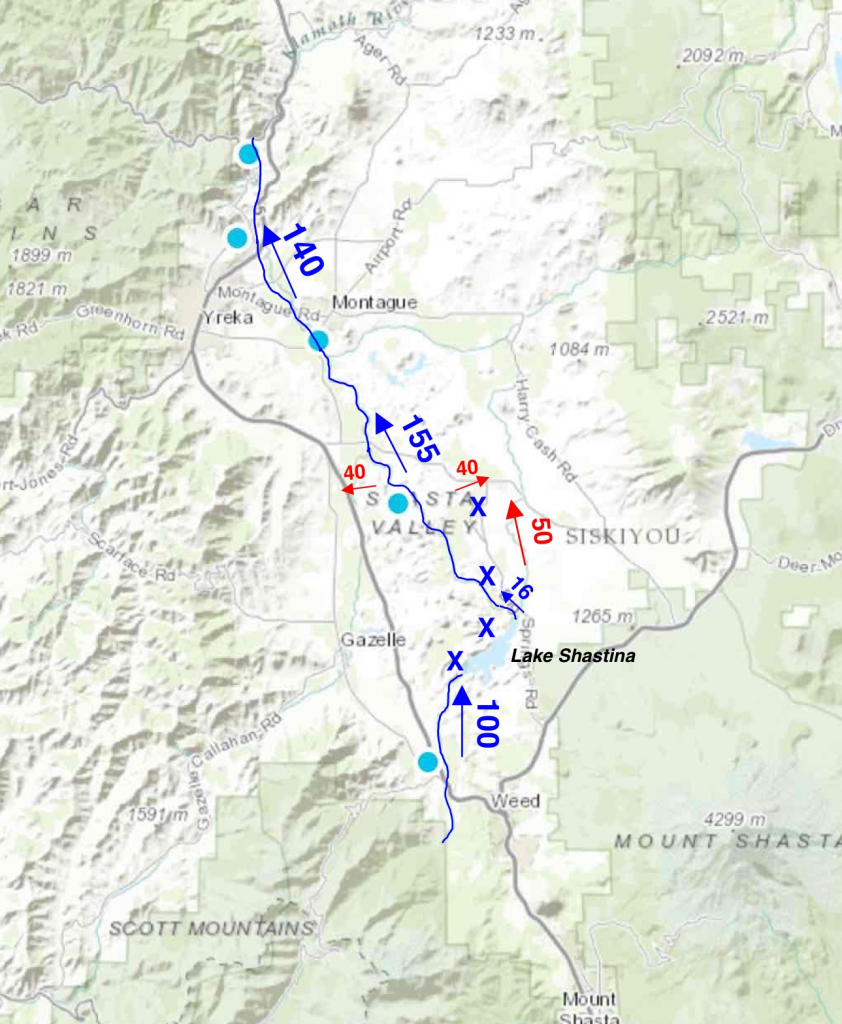

Just take a look at the present late May 2017 hydrology of the Klamath River (Figure 1). There was only 140 cfs flowing in the lower Shasta River. At the same time, there was 25,000 cfs flowing in the lower Klamath, 2000 cfs in the upper Klamath below Irongate Dam, and 2000 cfs in the Scott River. What is different is that most of the Shasta flow is spring fed, some of which is sustained through the summer. Of the roughly 300 cfs base flow in the river in late May 2017, about 200 was from springs (Figure 2). By mid-summer, flow out of the Shasta River into the Klamath will drop to about 50 cfs, with agricultural diversions from the Shasta at about 150 cfs. October through April streamflow is generally sufficient to sustain the fall-run salmon population. Summer flows are no longer sufficient to sustain the once abundant Coho and spring-run Chinook salmon.

Figure 1. Lower Klamath River with late May 2017 streamflows in red. Note Shasta River streamflow was only 140 cfs near Yreka, California. Data source: CDEC.

Figure 2. Selected Shasta River hydrology in late May 2017. Roughly 150 cfs of the 300 cfs total basin inflow is being diverted for agriculture, with remainder reaching the Klamath River. Red numbers are larger diversions. The “X’s” denote major springs. Big Springs alone provides near 100 cfs. Of the roughly 100 cfs entering Lake Shastina (Dwinnell Reservoir) from Parks Creek and the upper Shasta River and its tributaries, only 16 cfs is released to the lower river below the dam. Red numbers and arrows indicate larger agricultural diversions. Up to 15 cfs is diverted to the upper Shasta River from the north fork of the Sacramento River, west of Mount Shasta.