August 2023 has come to an end, following the second “Super Moon” of the month – a Blue Moon. The first full moon of the month was called a “Sturgeon Moon,” originally coined in reference to the ease of catching sturgeon in the Great Lakes during a full moon in summer. The cycle began with the quarter moon and neap tide on July 24 until the full moon on August 1.1

This year’s Super Moons have made a mess of San Francisco Bay, as they did in summer 2022. This year’s August moons have again, regrettably, led to a die-off of sturgeon and other Bay fish.2 The Super Moons’ strong tides caused warm water from the Delta to drain into the Bay, making the usually cool Bay unseasonably warm. (The ocean Blob may have added to some of this summer’s warm Bay water.) The warm water and the associated algal blooms (and their die-offs) have led to unprecedented low dissolved oxygen levels in the Bay, which can kill fish.

While the degree of harm has not been as bad as last year’s summer blooms that were aggravated by the 2022 drought, this year’s algal blooms have also harmed fish despite generally beneficial wet-year conditions. Last summer, there was die-off of nearly a thousand adult white sturgeon in the greater San Francisco Bay due to algal blooms. More dead white sturgeon adults also showed up on Bay beaches again this summer.3

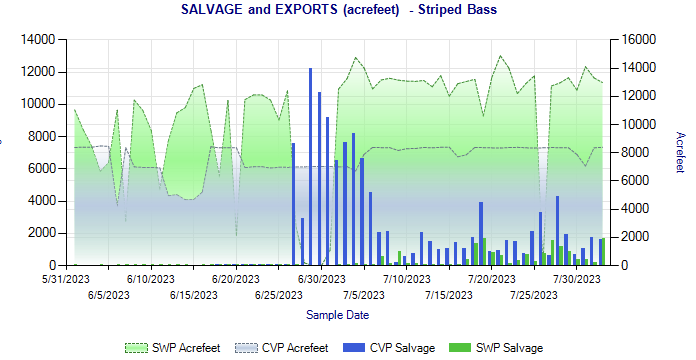

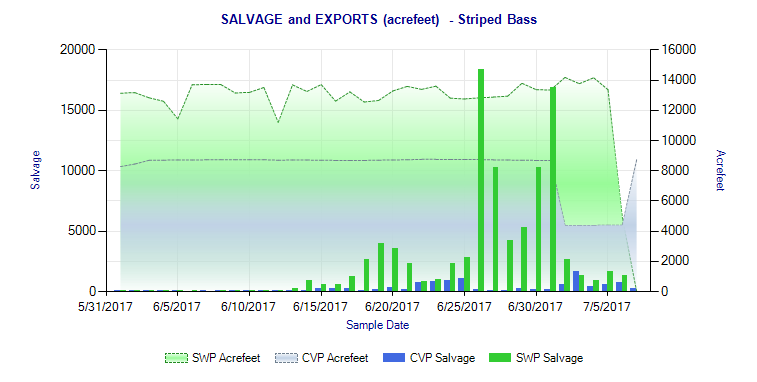

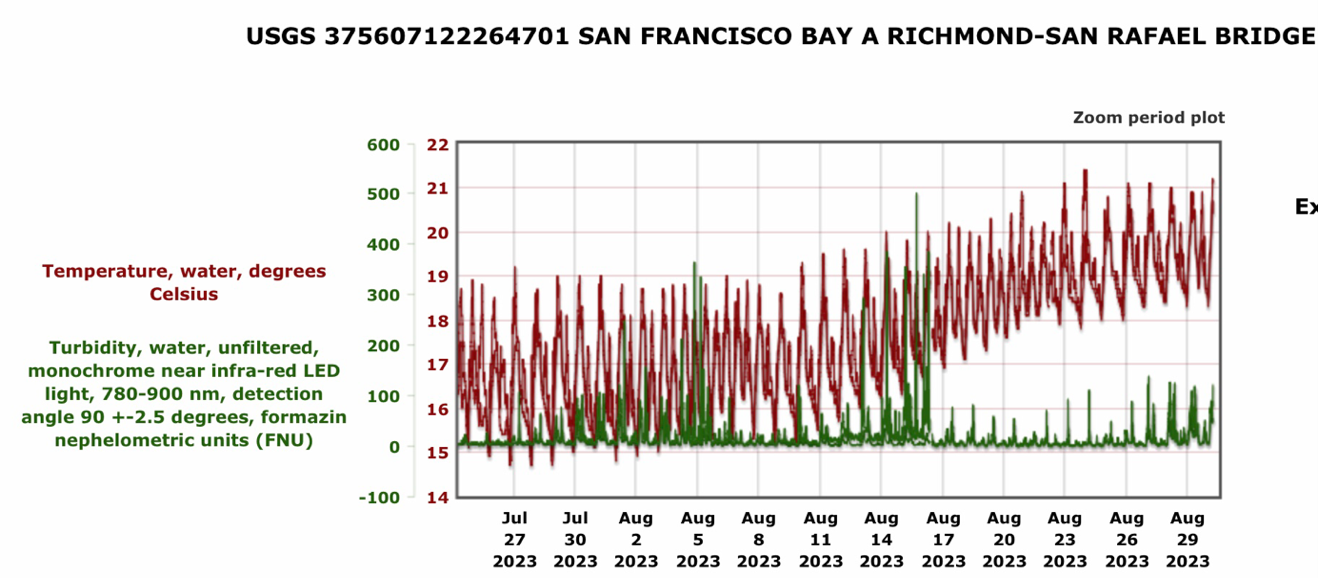

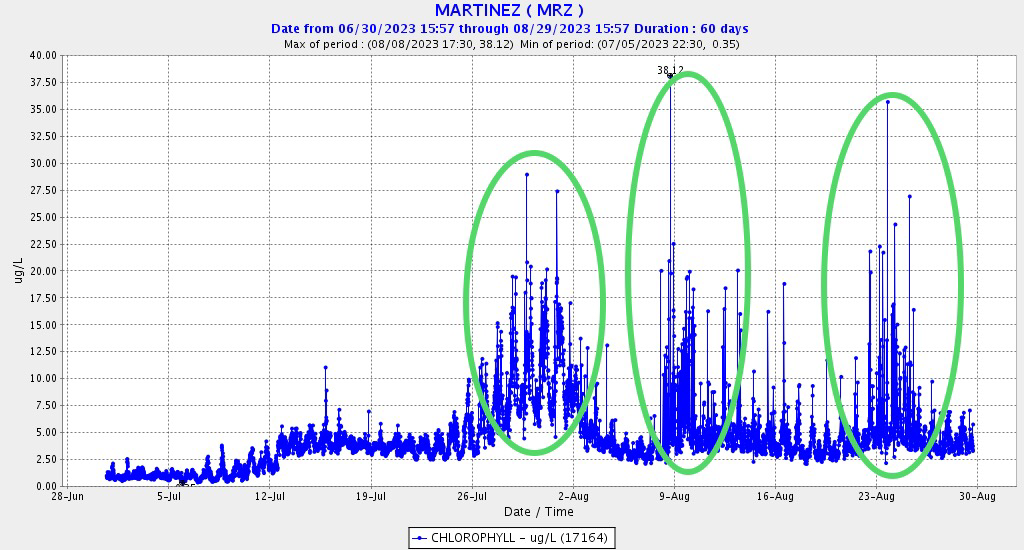

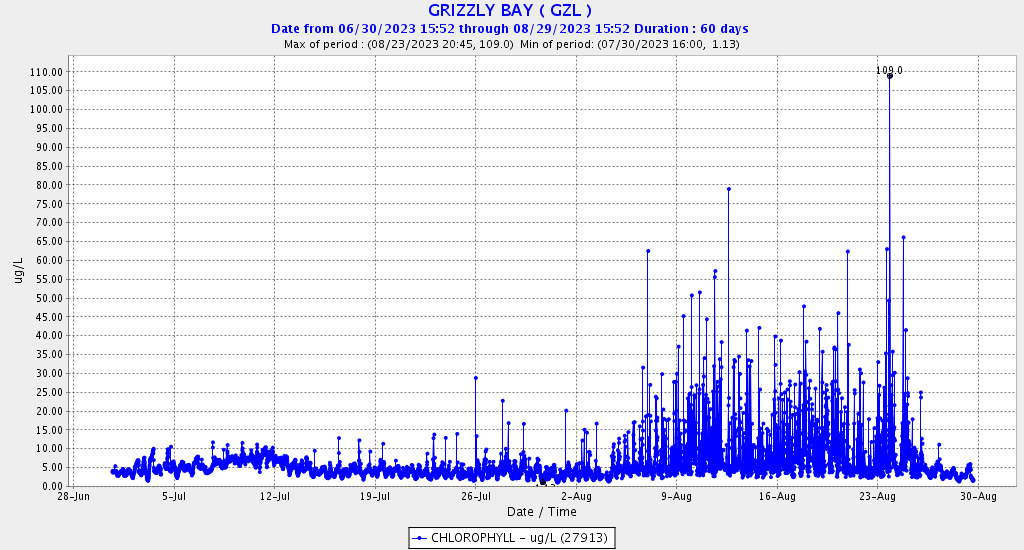

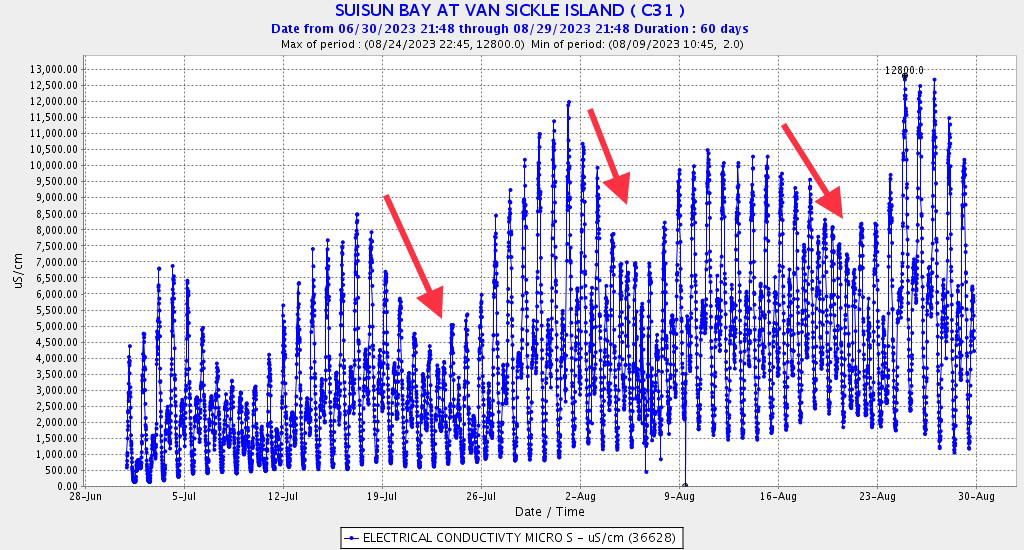

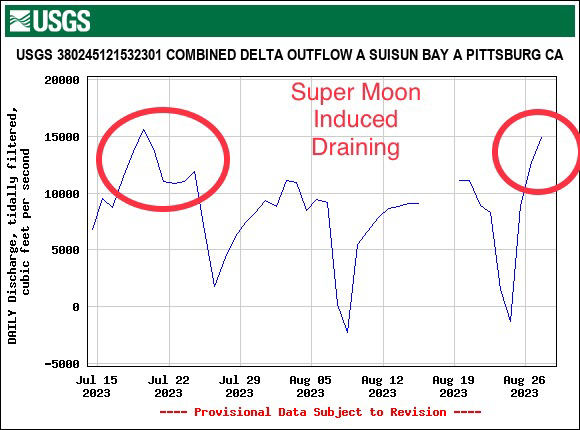

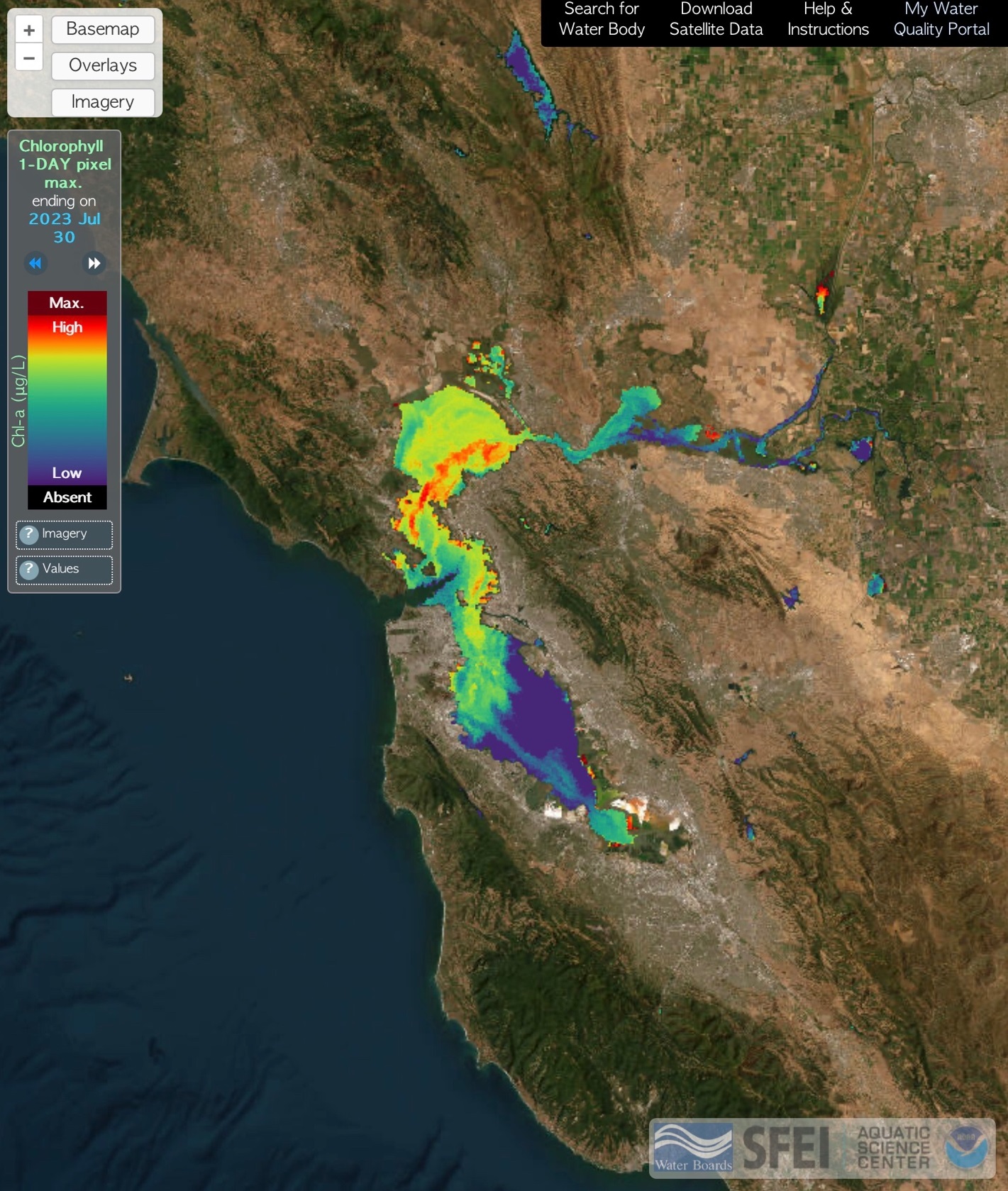

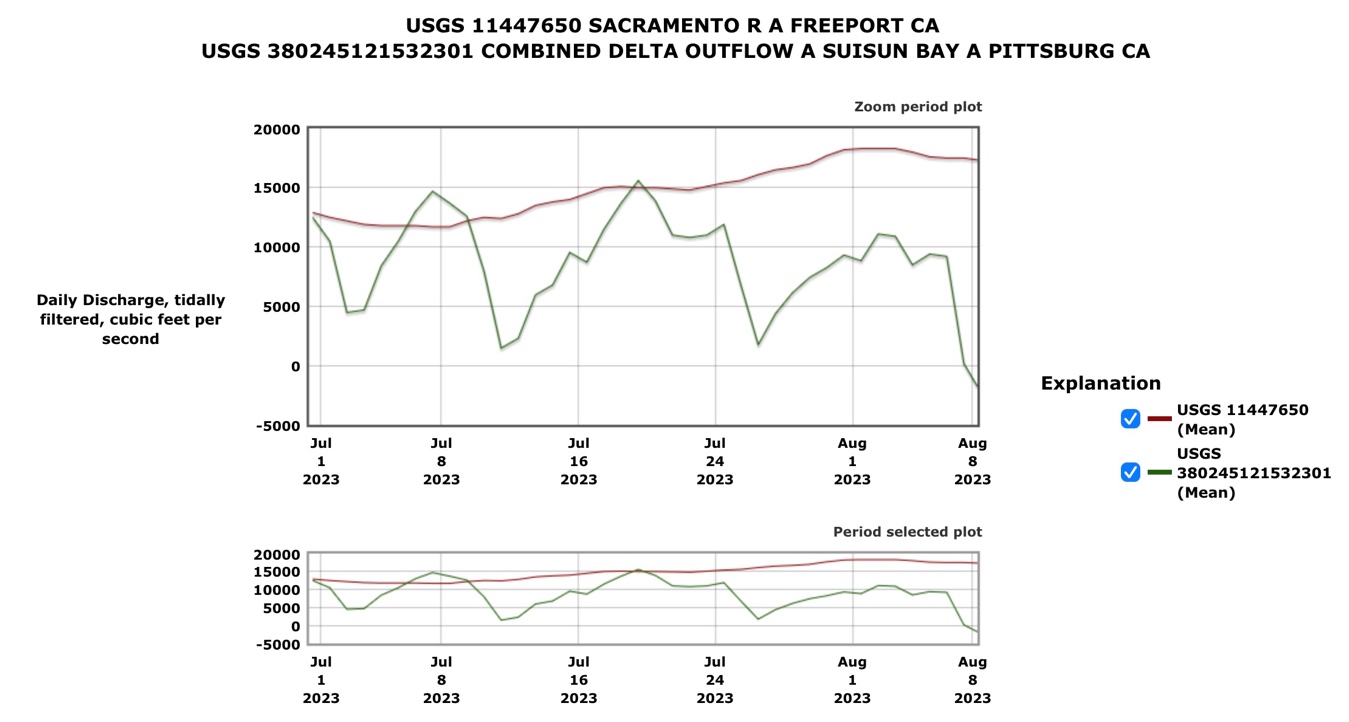

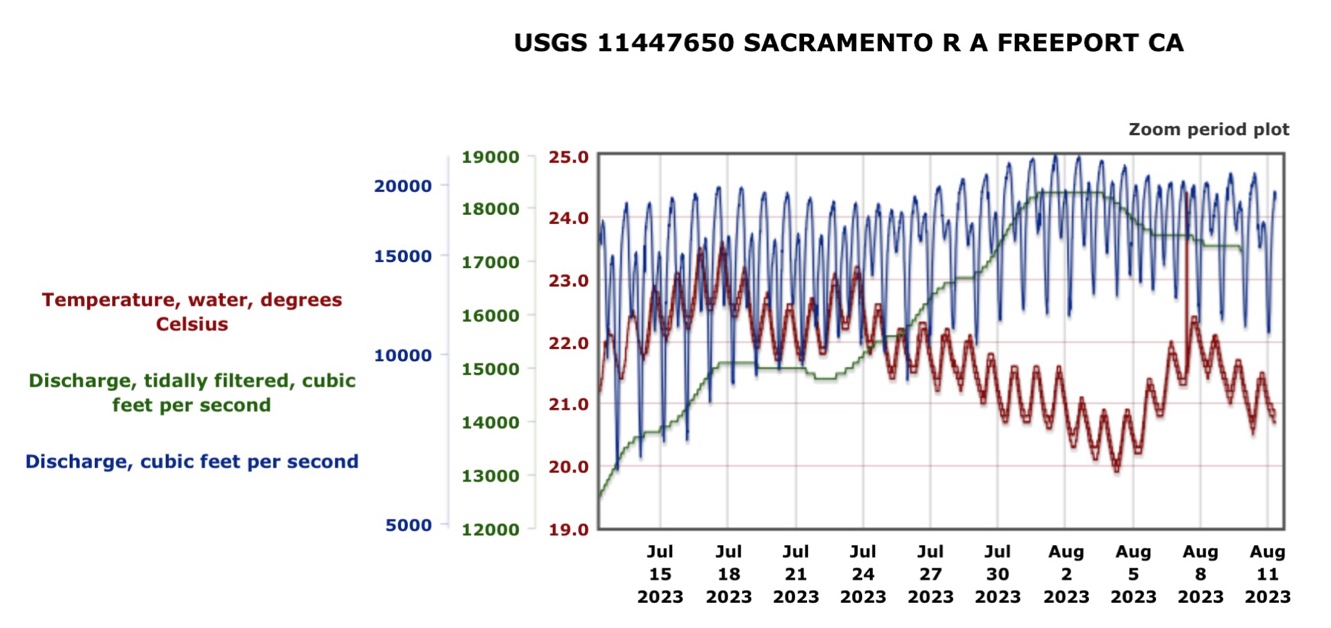

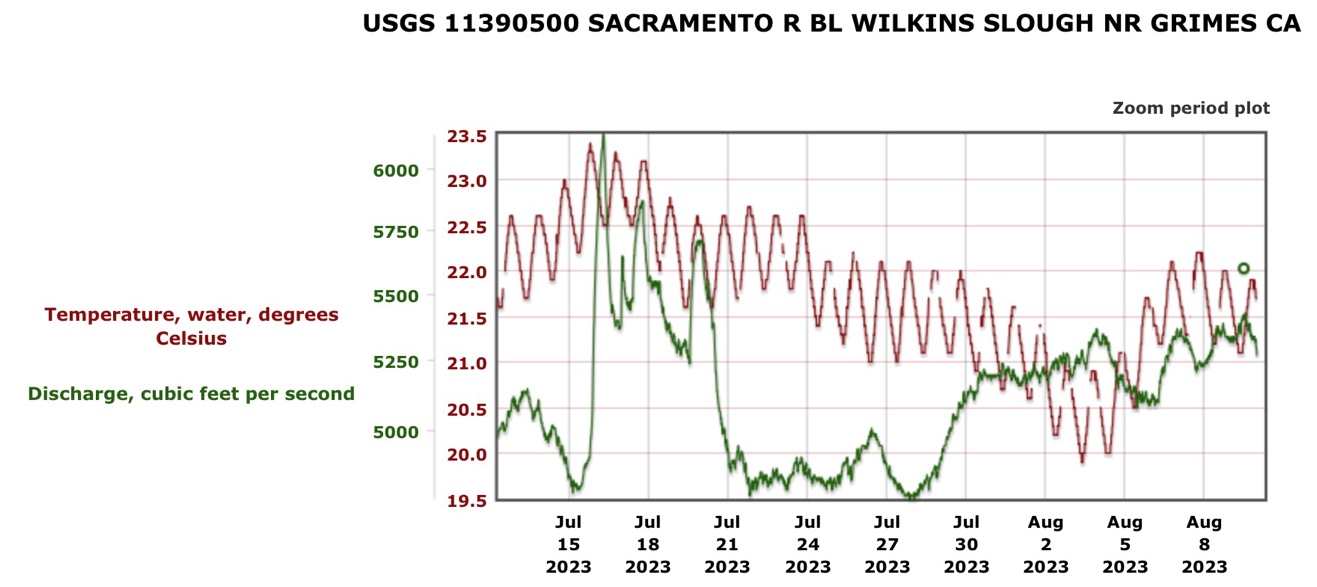

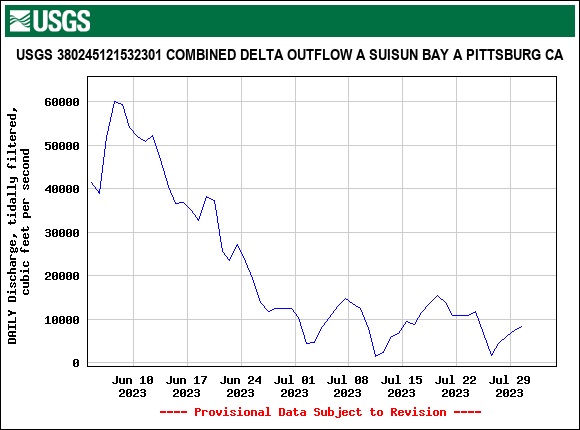

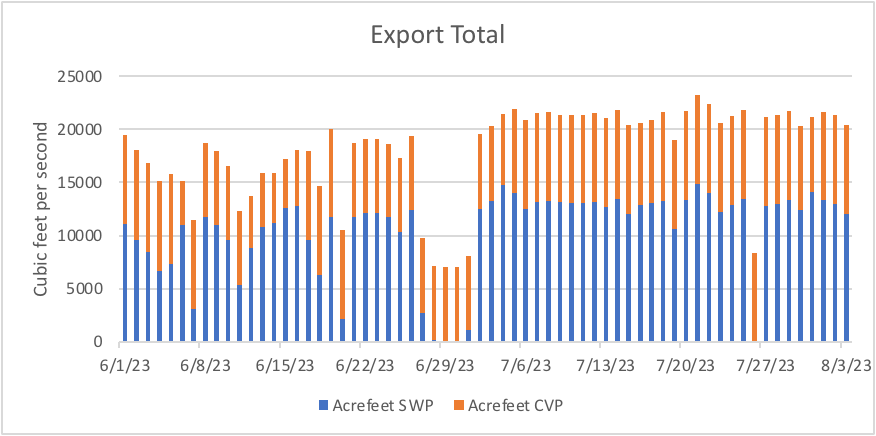

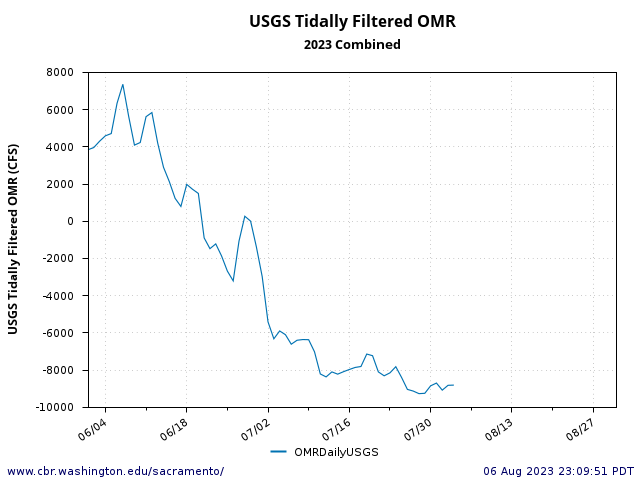

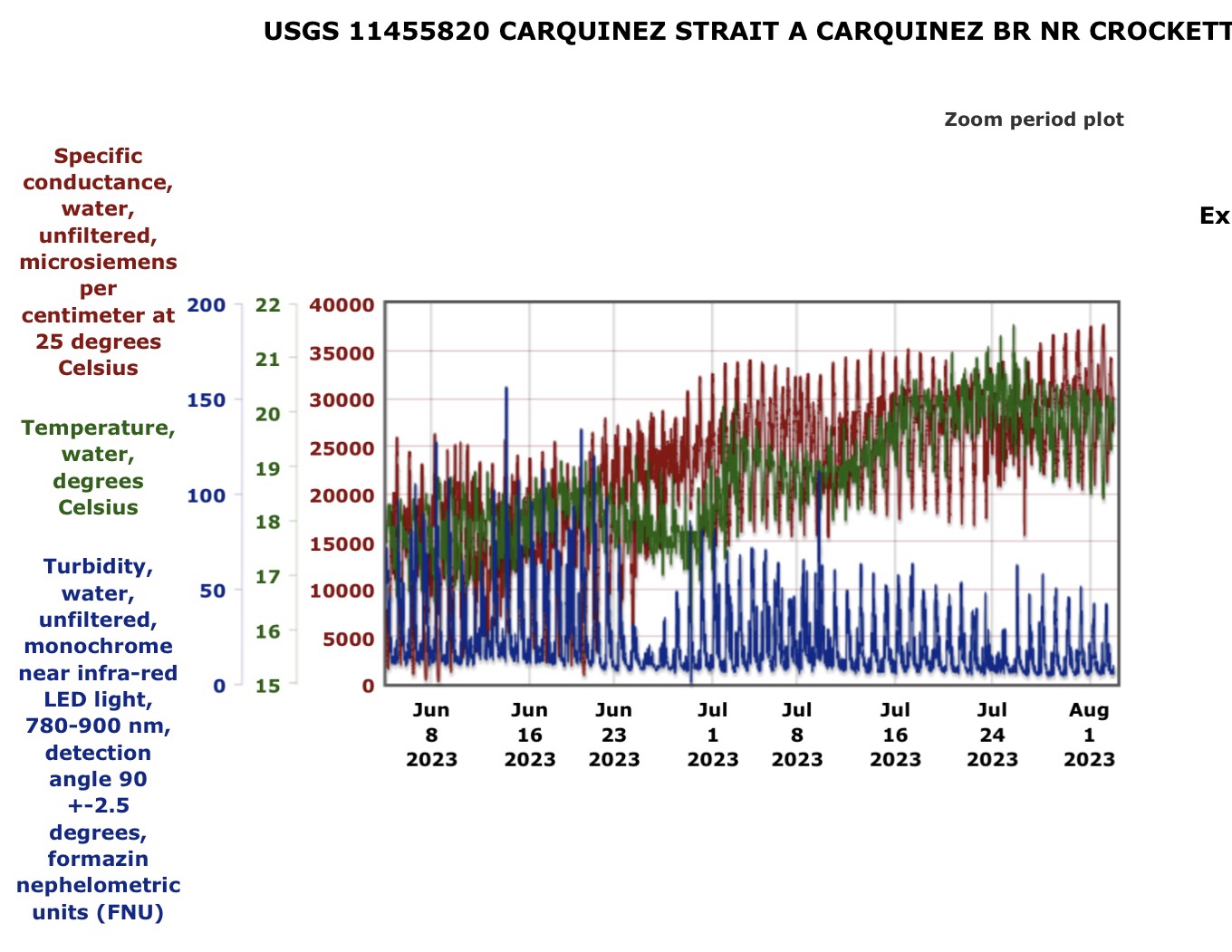

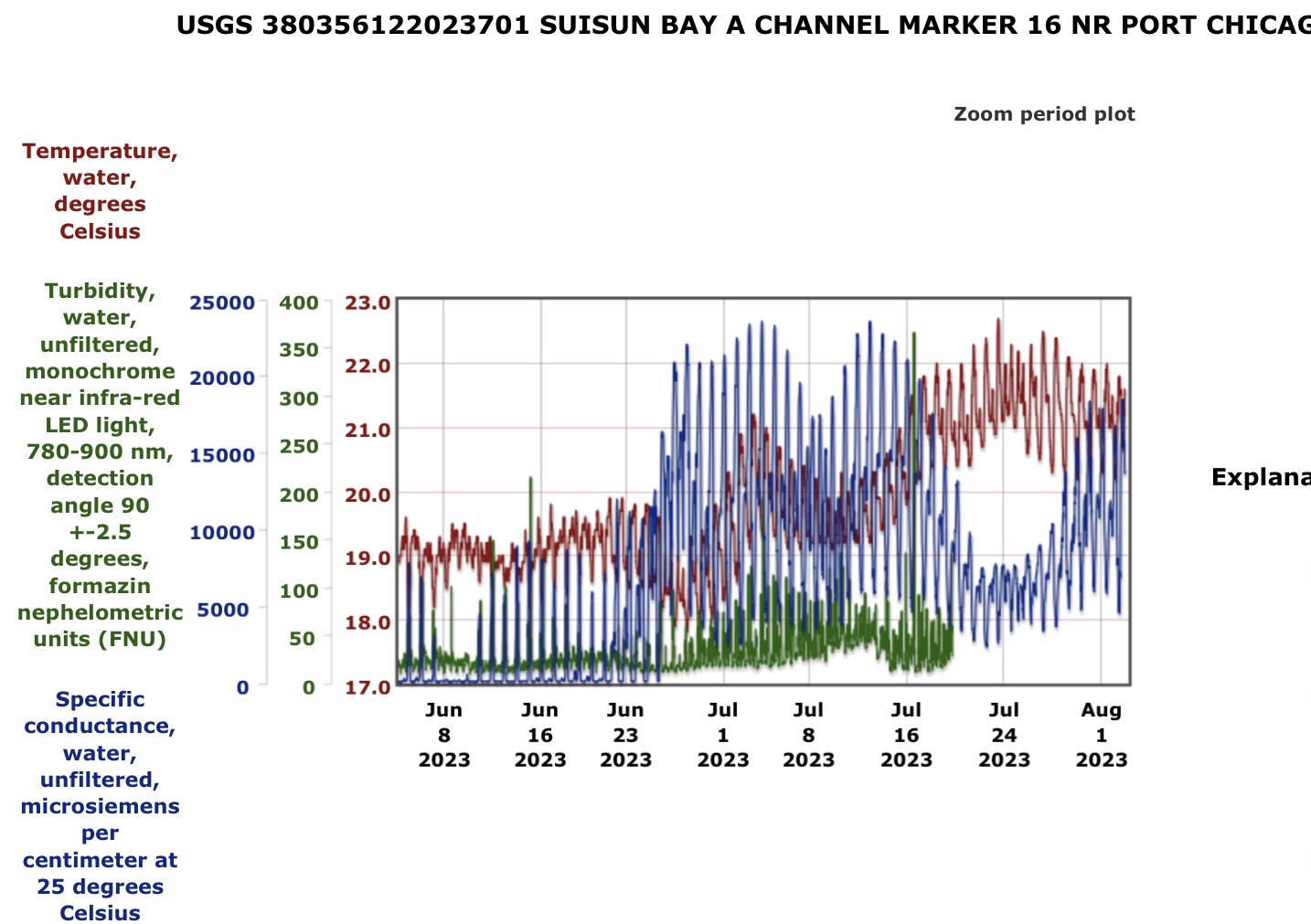

The Bay turned warmer under this summer’s Super Moons than under those last summer (Figure 1). Blooms are still happening, as indicated by high turbidities and chlorophyll levels in portions of the Bay (Figures 1-3). The draining of warm Delta water to the Bay just before the 2023 Super Moons (Figures 4 and 5) warmed the Bay (Figure 6). Low dissolved oxygen continues to plague the Bay (Figure 6). The most recent bloom is depicted in Figures 7 and 8.

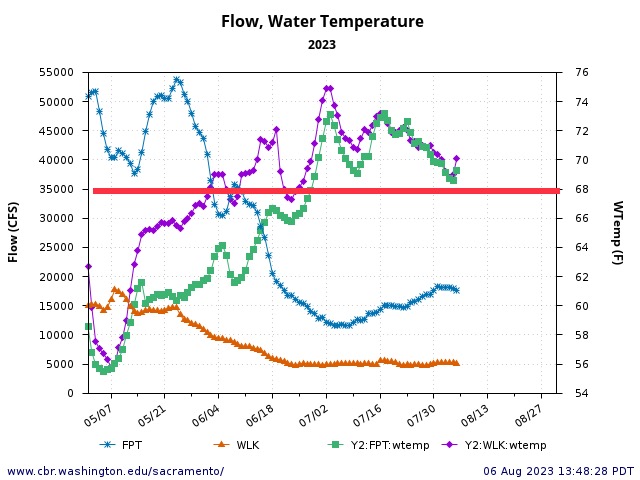

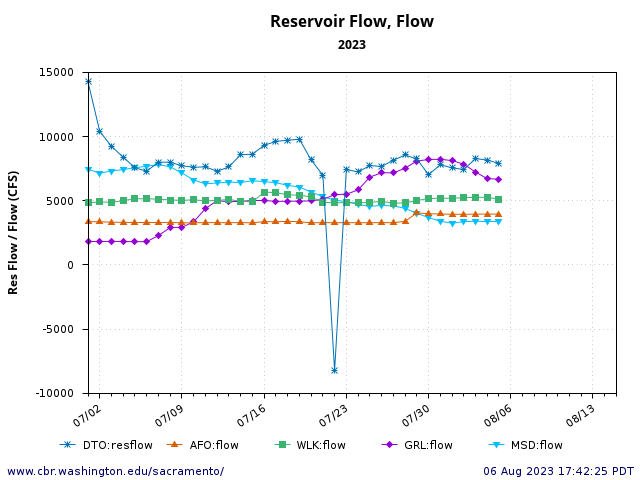

The summer 2023 Super Moons and their algal blooms make a complicated story, with the effects of various factors implicated in the blooms, and their role in fish die-offs in the Bay, yet to be fully determined. My concern centers on how warm the Delta becomes in summer before it drains into the Bay during the lunar tidal cycles (Figure 9). The lower rivers and Delta received too little flow from major Central Valley reservoirs for a wet year with full reservoirs. This is an increasing trend that deserves a lot more attention to ensure protection of the Bay’s fish and other public trust values. Otherwise, the trend will simply be chocked up to climate change.

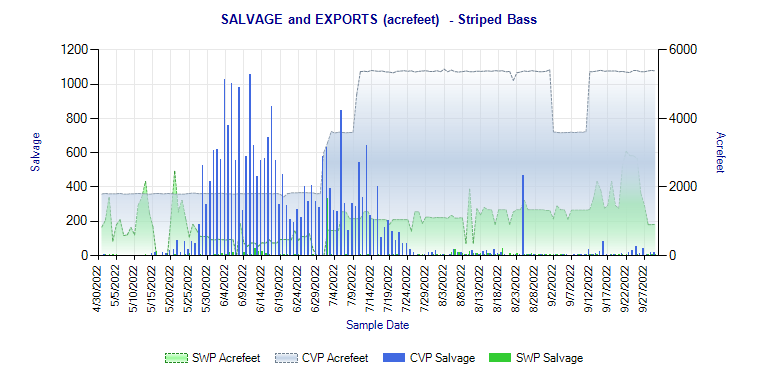

Figure 1. North Bay (San Pablo Bay at Richmond Bridge) water temperature and turbidity in summer 2023. Note the presence of the three blooms indicated by high turbidity levels (>100 FNUs)

Figure 2. Chlorophyll levels at Martinez CA gage between East and North San Francisco Bay in summer 2023. Note three periods (green circles) of blooms located at this site.

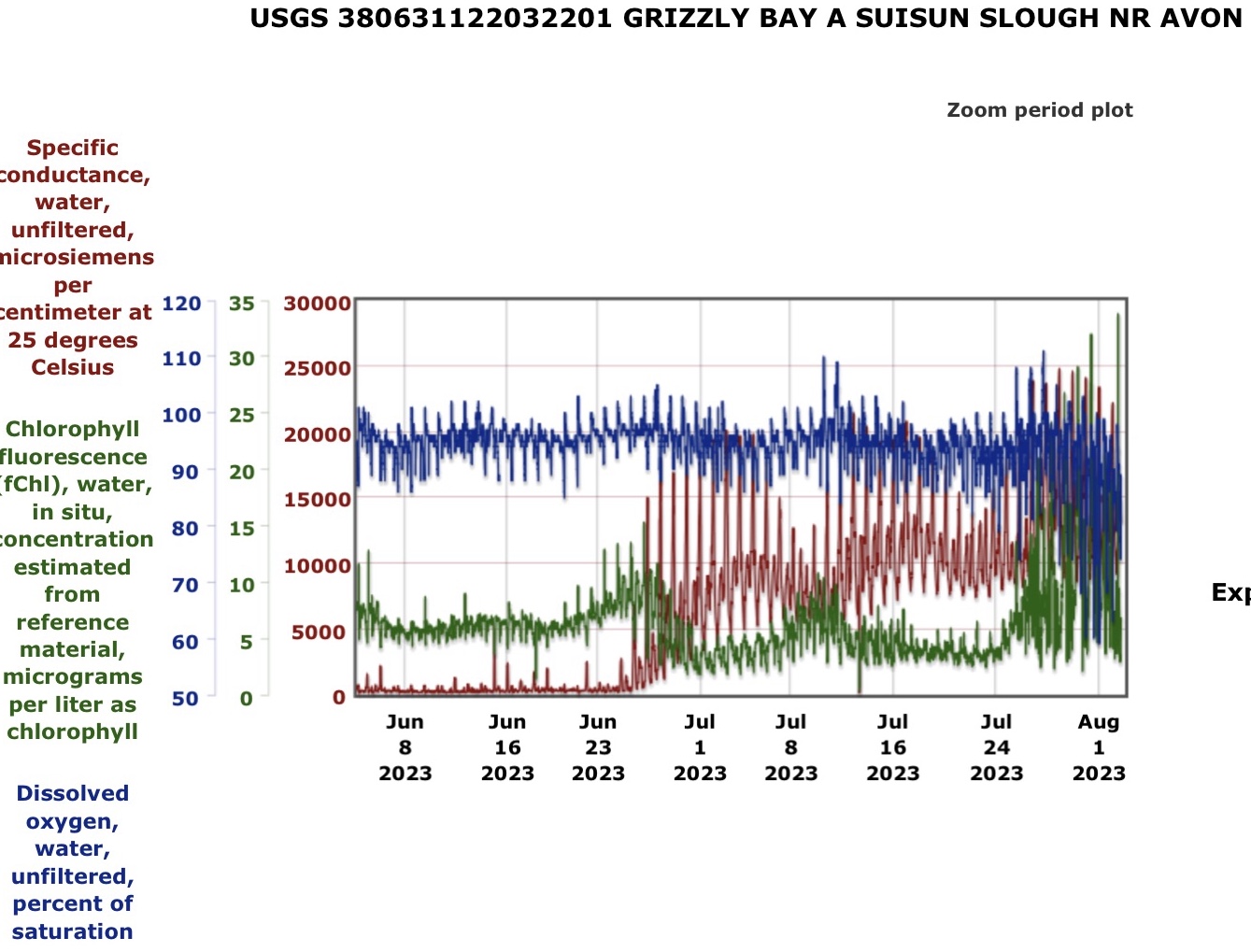

Figure 3. Chlorophyll levels at Grizzly Bay gage (in northwest East Bay) in summer 2023.

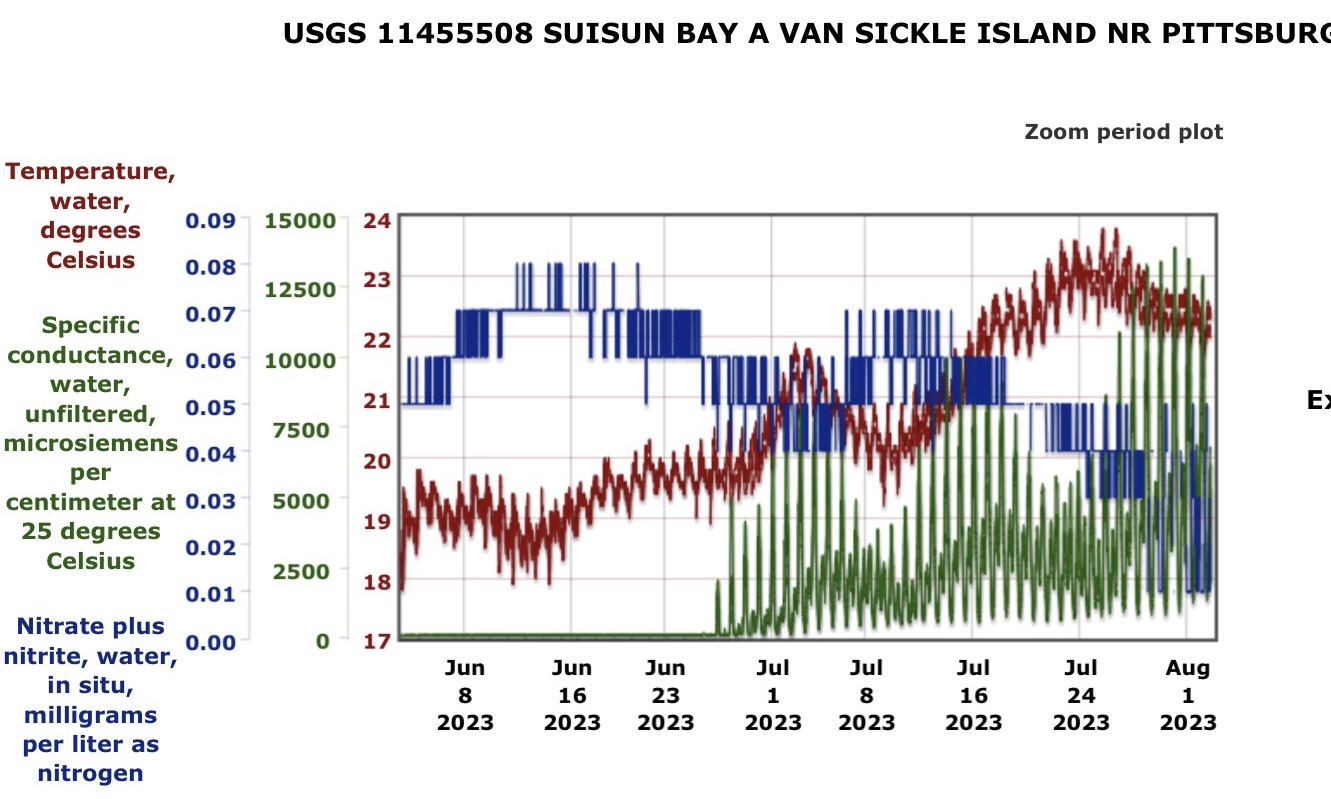

Figure 4. Salinity (EC) at eastern Suisun Bay gage (in east Bay) in summer 2023. Red arrows indicate periods of draining prior to and between full moons.

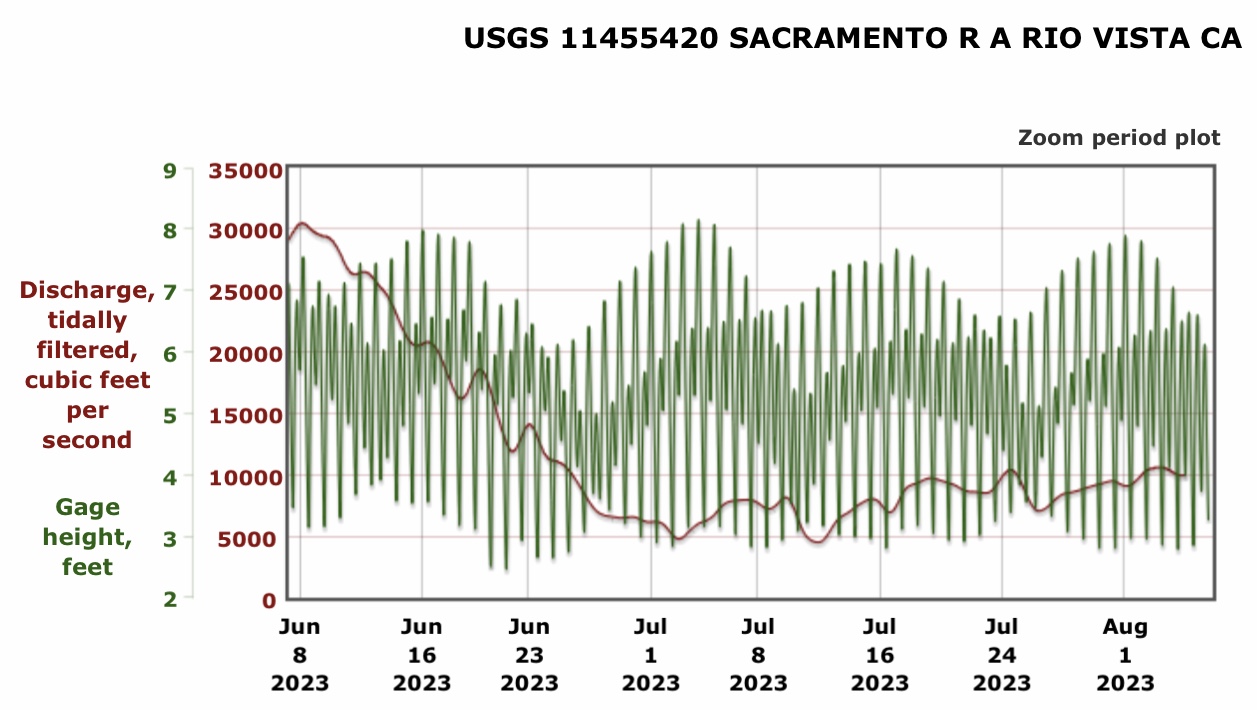

Figure 5. Daily average (tidally filtered) discharge at Pittsburg gage in Suisun Bay summer 2023. Red circles indicate drainage rates to Suisun Bay prior to two Super Moons (August 1 and 30).

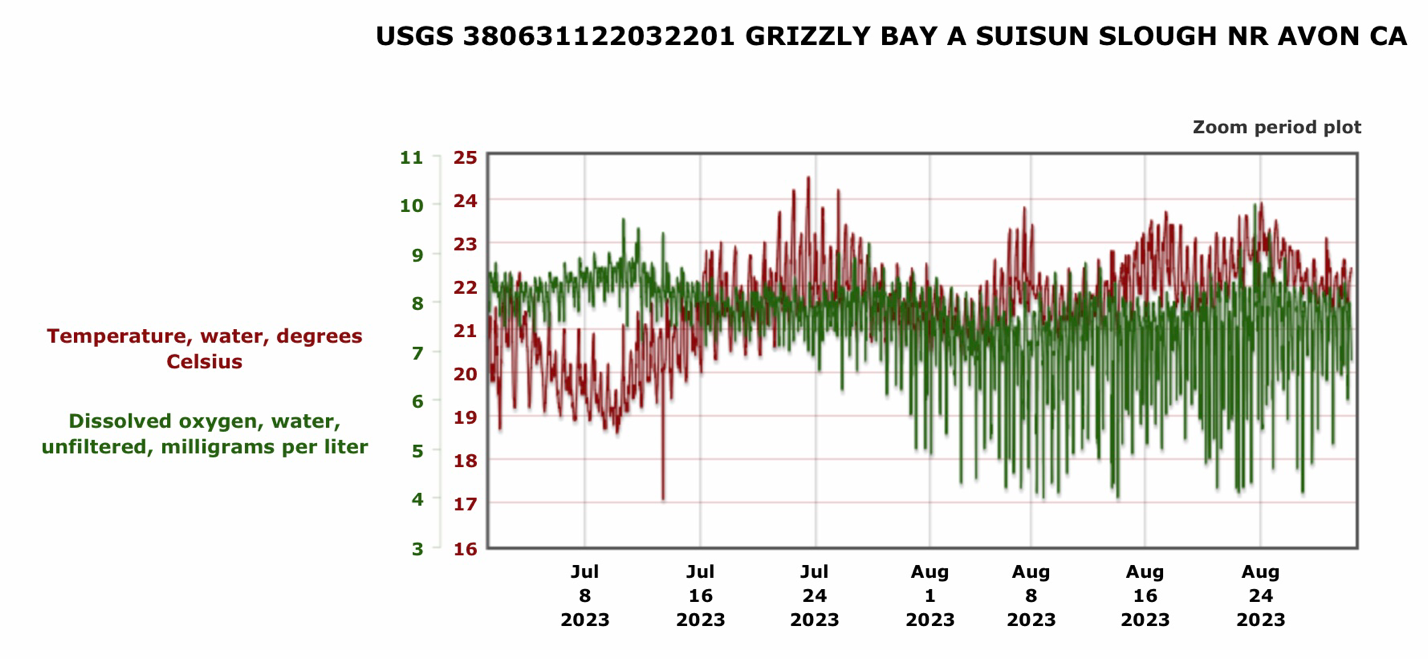

Figure 6. Hourly dissolved oxygen levels in Grizzly Bay in summer 2023. Note inverse relationship with chlorophyll levels in Figure 4. The low dissolved oxygen levels (<5 mg/l) began with the first bloom (August 1) and continued through August. Also note the Bay water quality standard is a minimum 6 mg/l dissolved oxygen level for fish health.

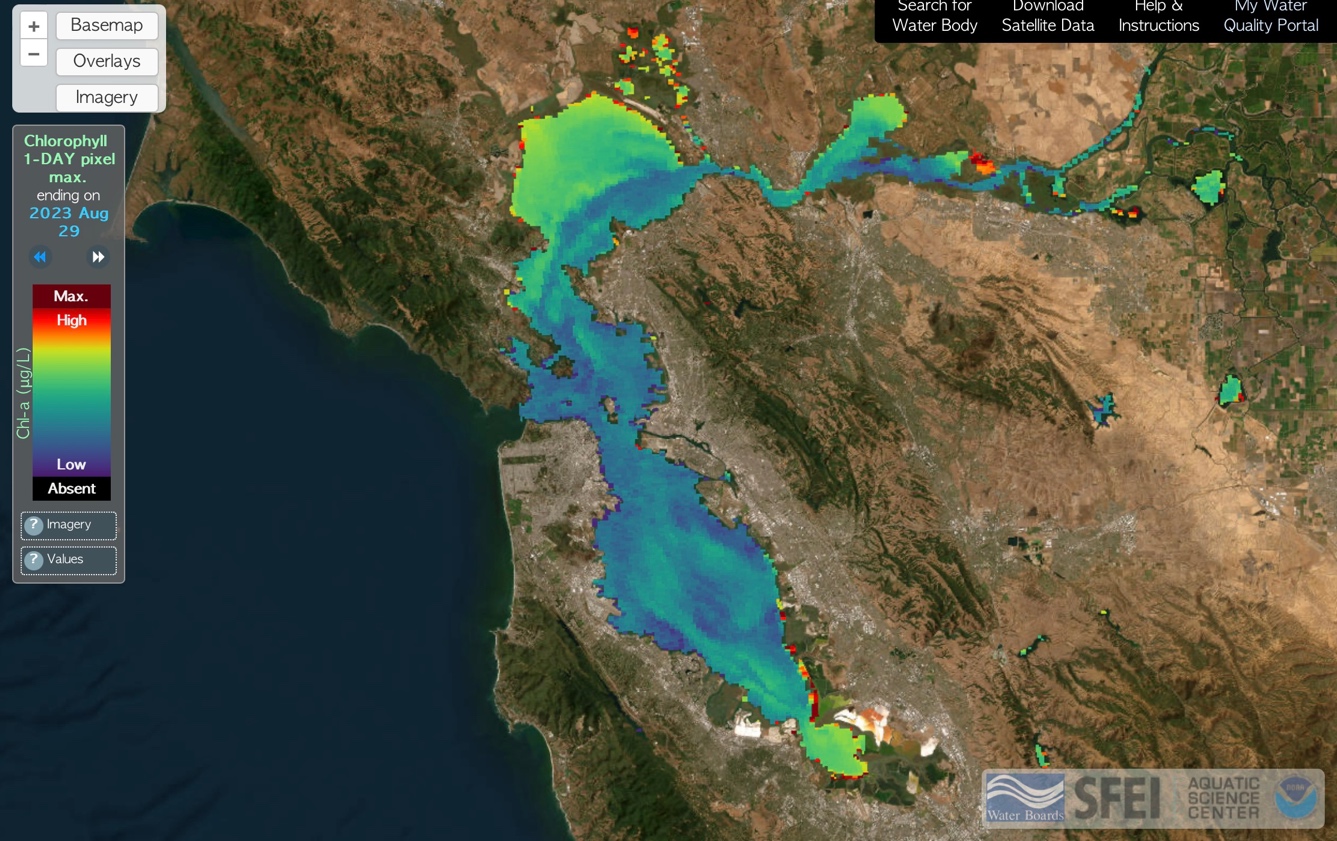

Figure 7. Satellite imagery of chlorophyll levels in San Francisco Bay on 8/29/2023.

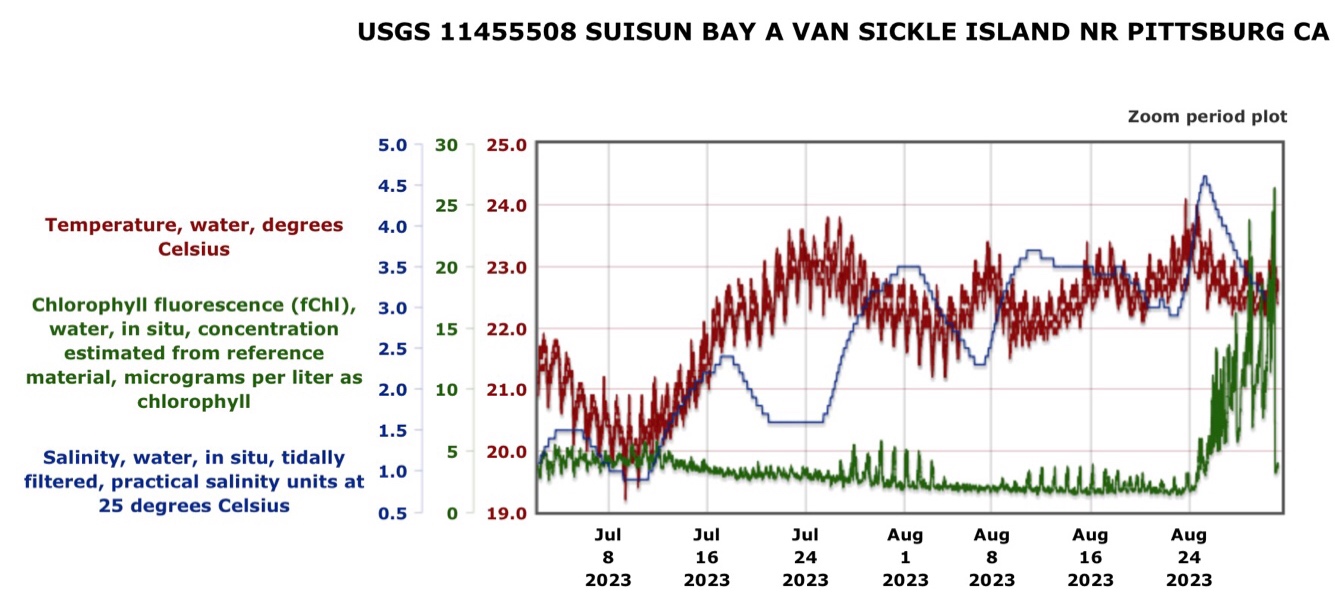

Figure 8. Water temperature, chlorophyll, and salinity in Suisun Bay in summer 2023. Note algal bloom in late August that began after the late-August draining of the Delta into the Bay when water temperatures reached 24oC (75oF).

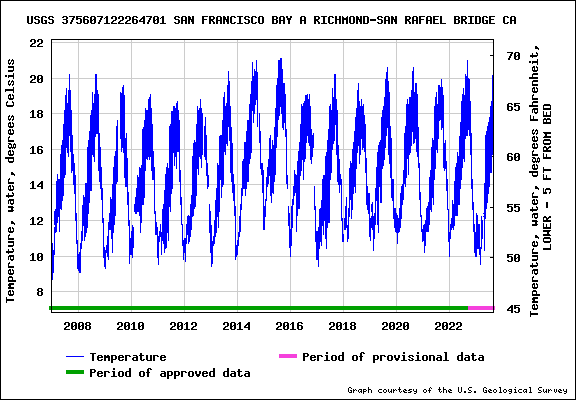

Figure 9. San Francisco Bay water temperatures from 2007-2023. Note 2023 reached 70oF (see Figure 2) a recent record reached not even reached in critical drought years 2014, 2015, and 2022.

- Spring tides always happen when the Moon is at the full or new phase, which is when the Sun, Moon and Earth are in alignment. Neap tides occur around the first and last quarter phase of the Moon, when the Moon’s orbit around Earth brings it perpendicular to the Sun. ↩

- https://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/?p=4398 ↩

- https://www.sfchronicle.com/climate/article/fishkill-18279379.php ↩

![Graph showing Striped bass Fall Midwater Trawl Survey Index (log10[index+1]) versus prior Summer Townet Index (log10). Select years labeled, with color of number showing year type: blue=wet, green=normal, and red=critically dry.](https://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/image1.jpeg)