In an April 19, 2020 blog post entitled Science of an underdog: the improbable comeback of spring-run Chinook salmon in the San Joaquin River, a UC Davis team describes the efforts over the past five years to recover spring-run Chinook salmon in the San Joaquin as a “good comeback story.” It is a great story – as far as it goes. Eighteen years of litigation and fifteen years of restoration work have put water back in a river that Friant Dam completely dried up in 1950. There are also some spring-run salmon in the river, and a few made it from near Fresno to the ocean and back in the last few years.

The goal of the reintroduction program is the long-term maintenance of a population of 30,000 spawning adults with negligible hatchery influence. The count for the 2019 run was 23. Reaching the goal is highly improbable in the present scheme of things.

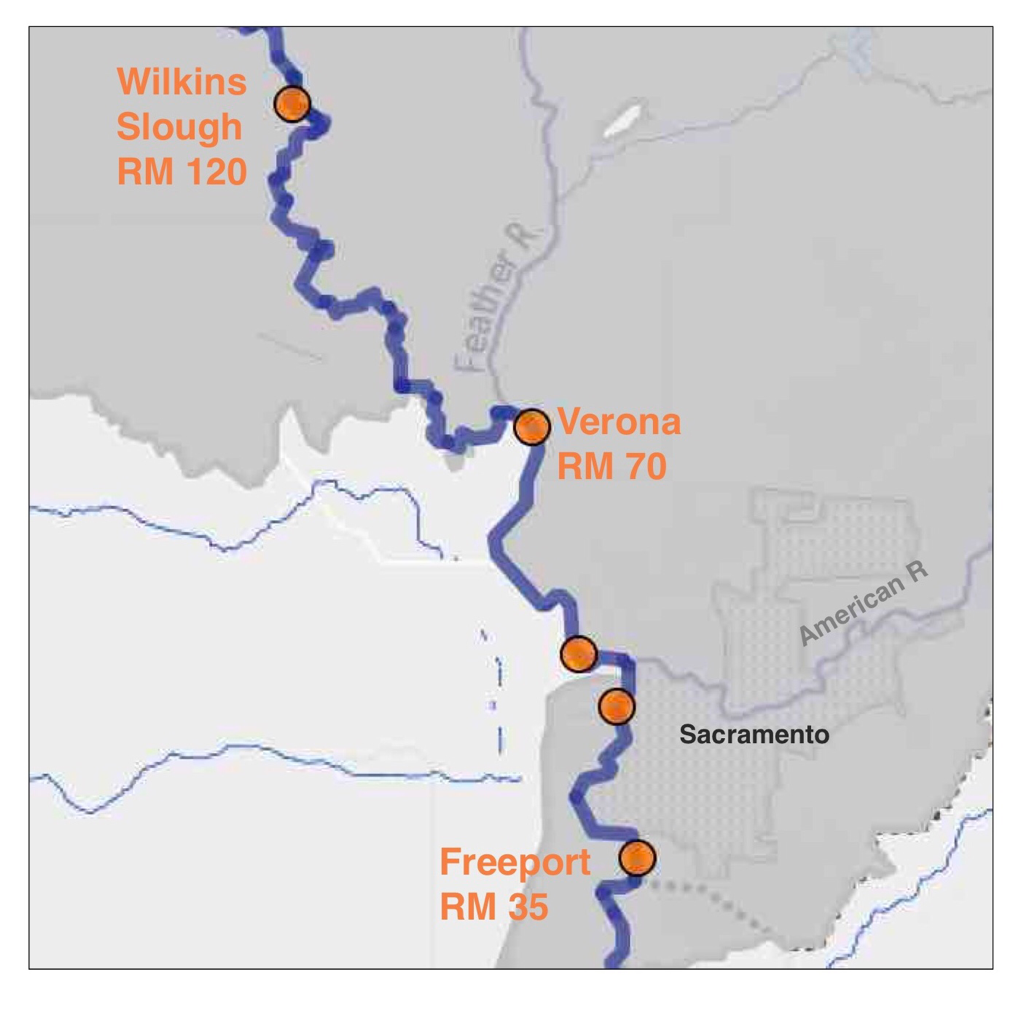

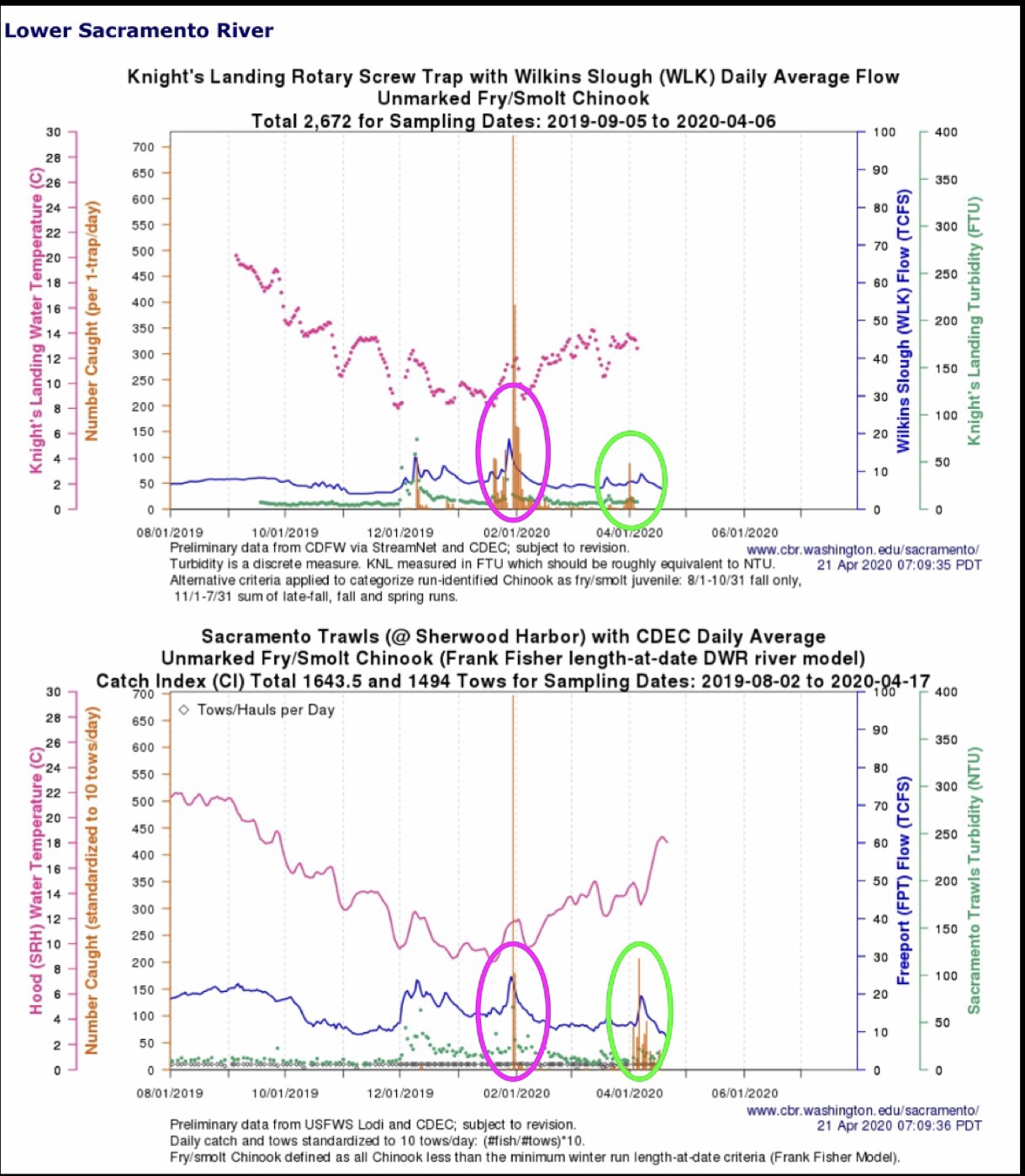

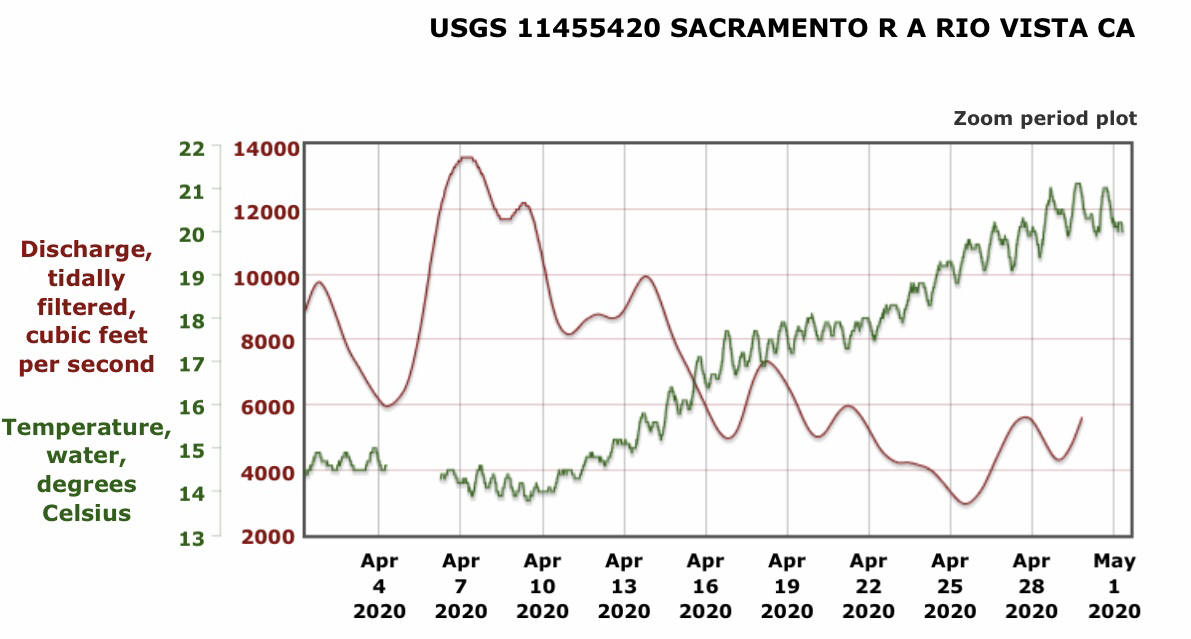

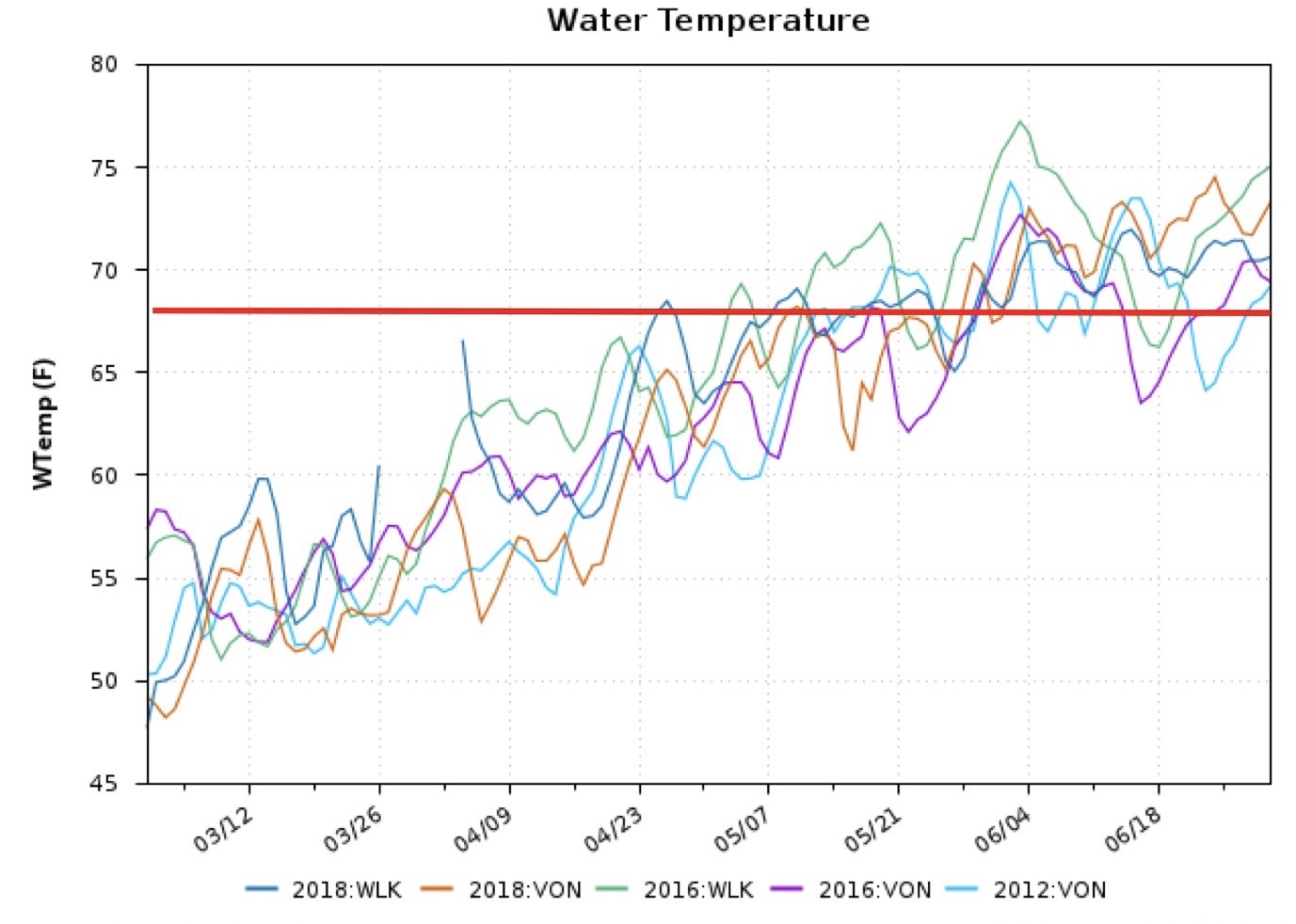

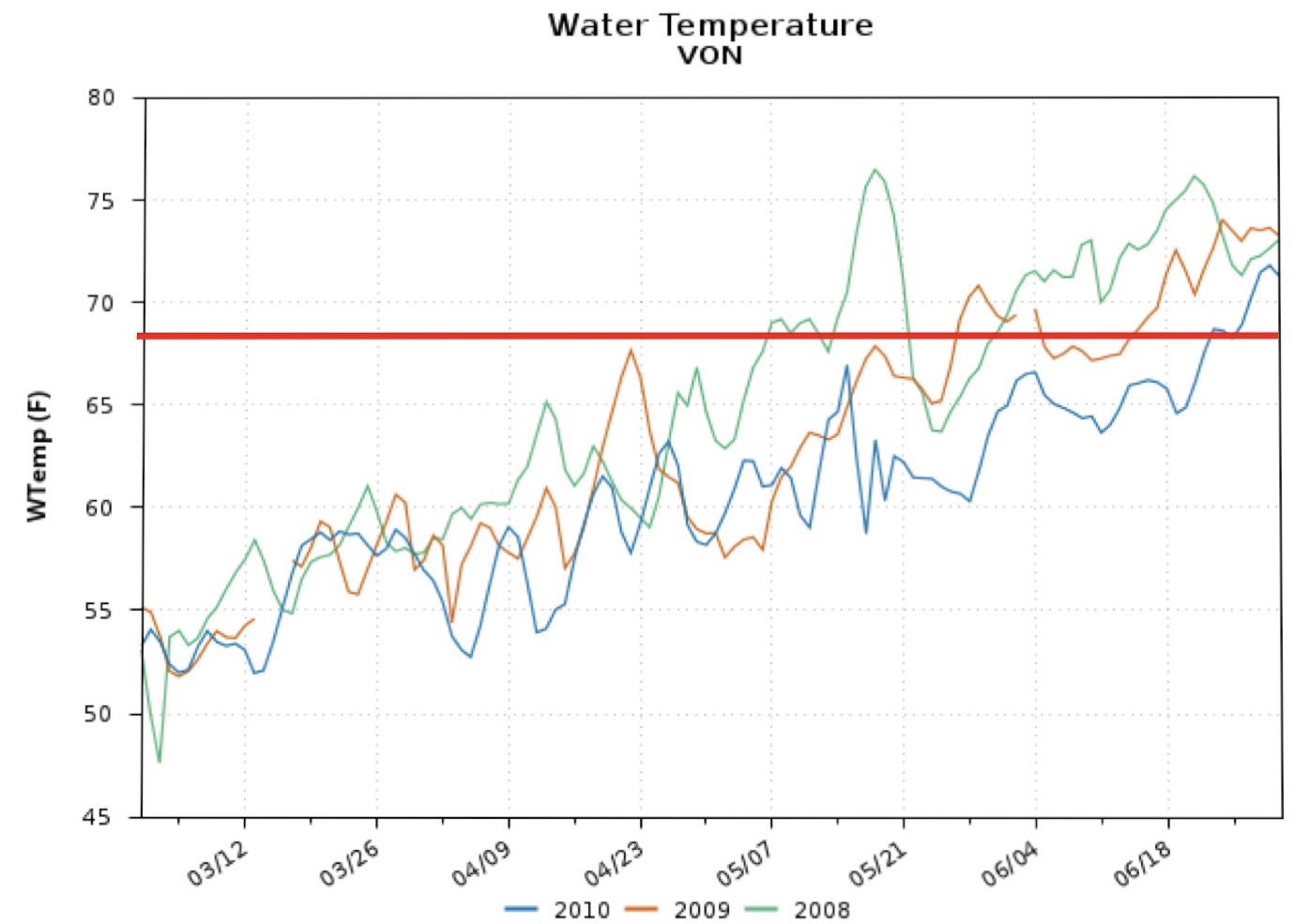

Why? As the UC Davis team stated: “Most of the tagged fish that enter the interior Delta simply don’t make it out.” Juvenile salmon from natural spawning areas and hatcheries do not survive downstream passage downstream to and through the Delta in necessary numbers to make the goal achievable. There are simply too many “obstacles.”

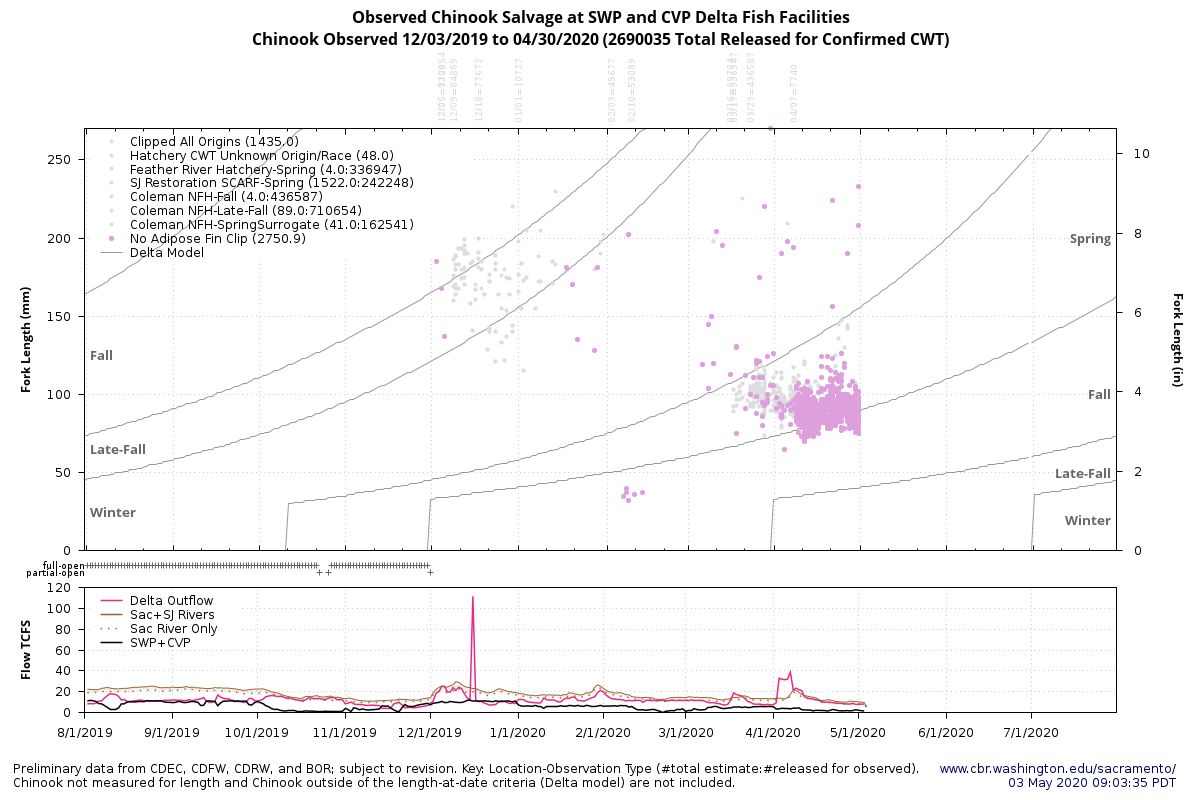

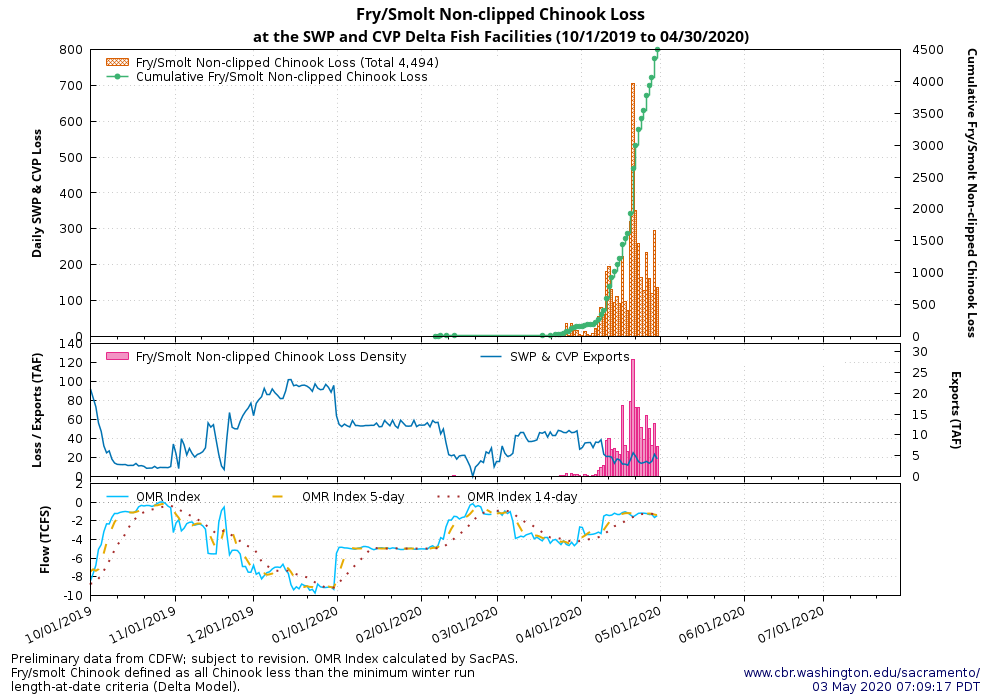

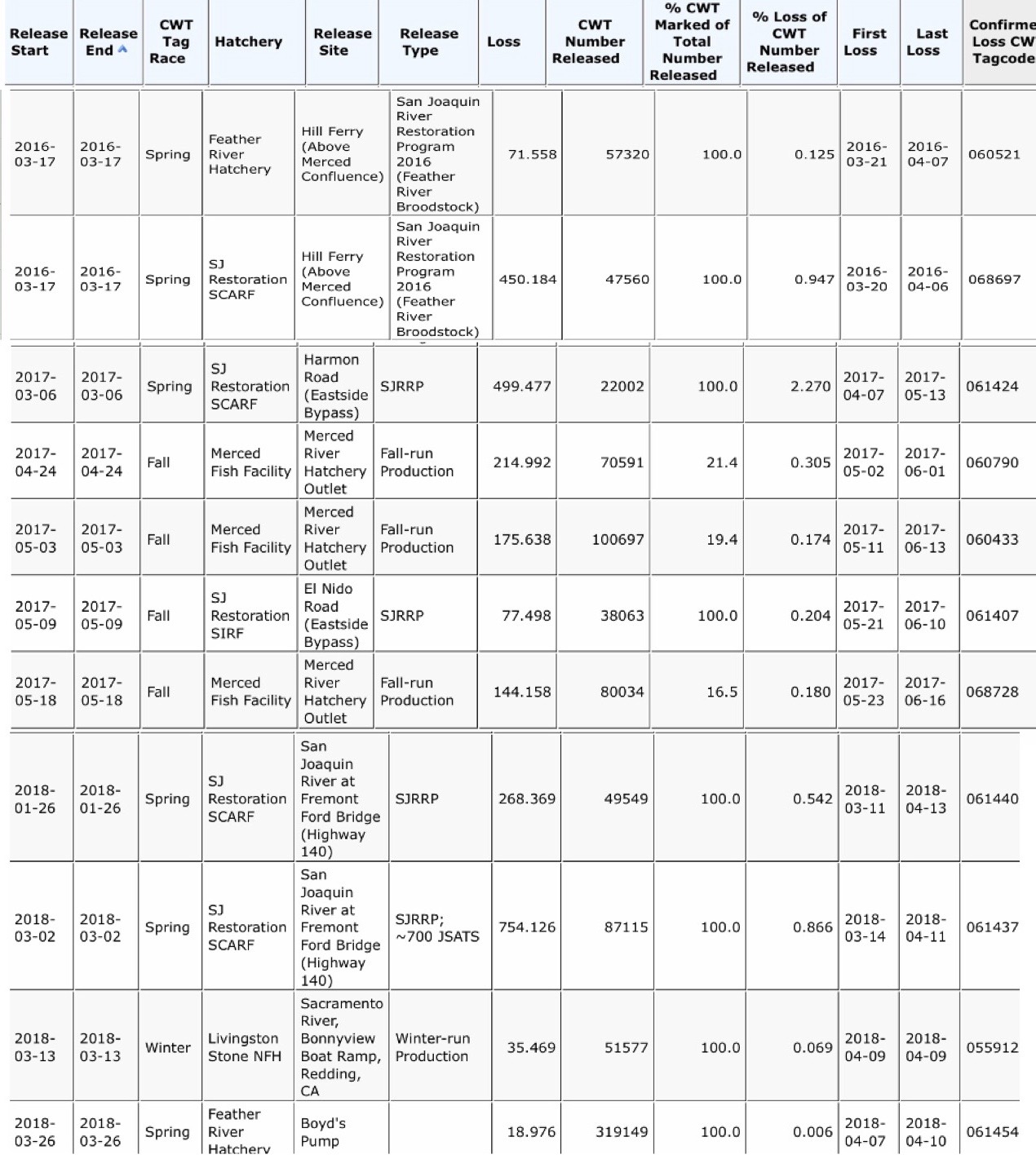

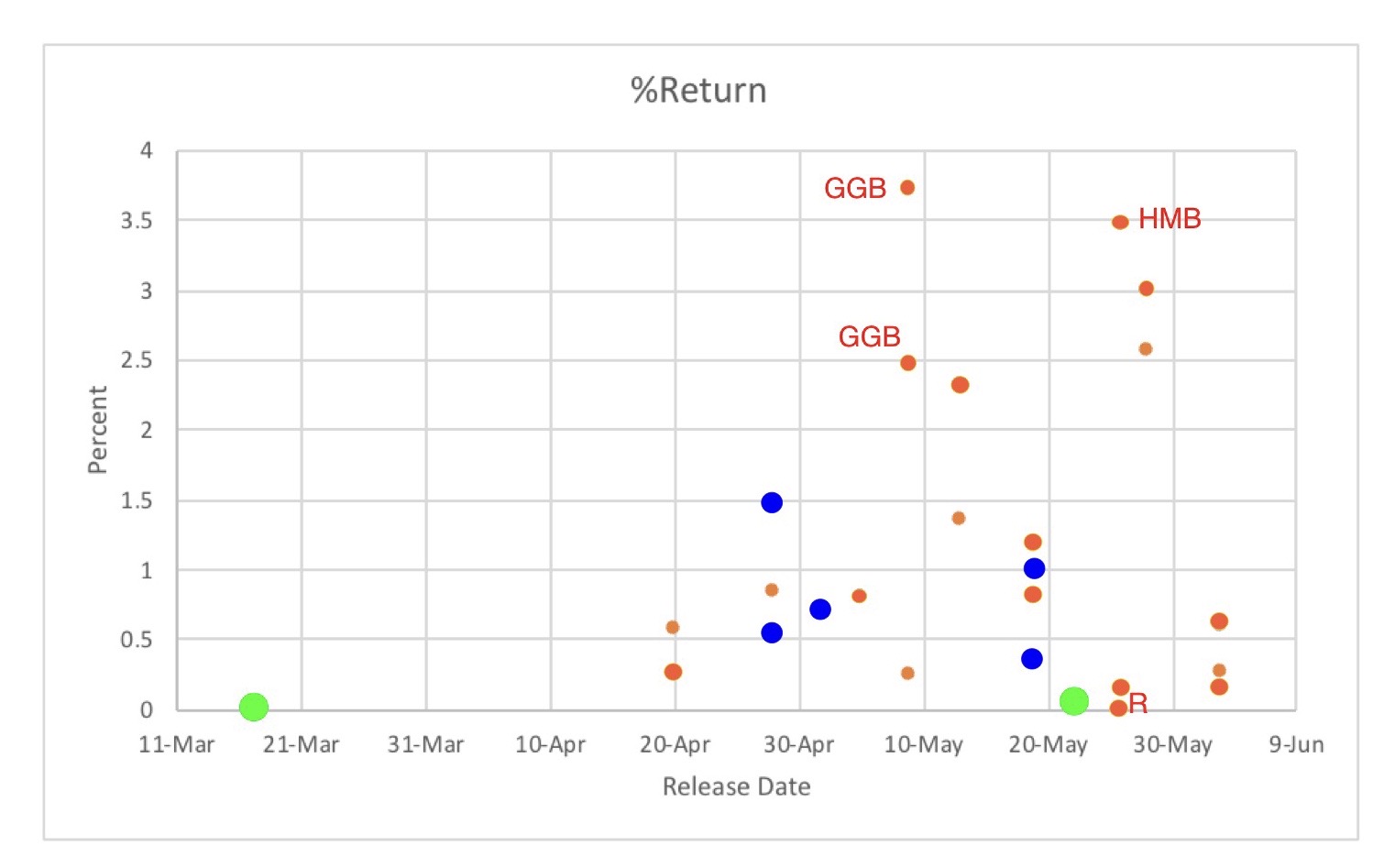

The UC Davis team also stated: “It is notably sad and ironic perhaps, that the quality of habitat in the lower river is so poor that the best migration path for salmon appears to be as a salvaged fish, trucked around the Delta by DWR or BOR staff.” The word “best” is just the wrong word to describe a path and procedure that is founded on a dysfunctional fish salvage system that at its best saves a tiny fraction of the fish that the Delta pumps pull off course and ultimately decimate. Returns of adult salmon to the San Joaquin River are extremely low (Figure 1). Department of Water Resources and Bureau of Reclamation “staff” collect and truck these totally misdirected, stressed, and abused fish, and dump them into the waiting mouths of predators in the west Delta, not even bothering to truck salvaged fish to the Bay. Compared to Sacramento River hatchery smolts, the odds of San Joaquin hatchery smolts being “salvaged” are one to two orders of magnitude higher (Table 1).

What could help recover San Joaquin River spring-run salmon?

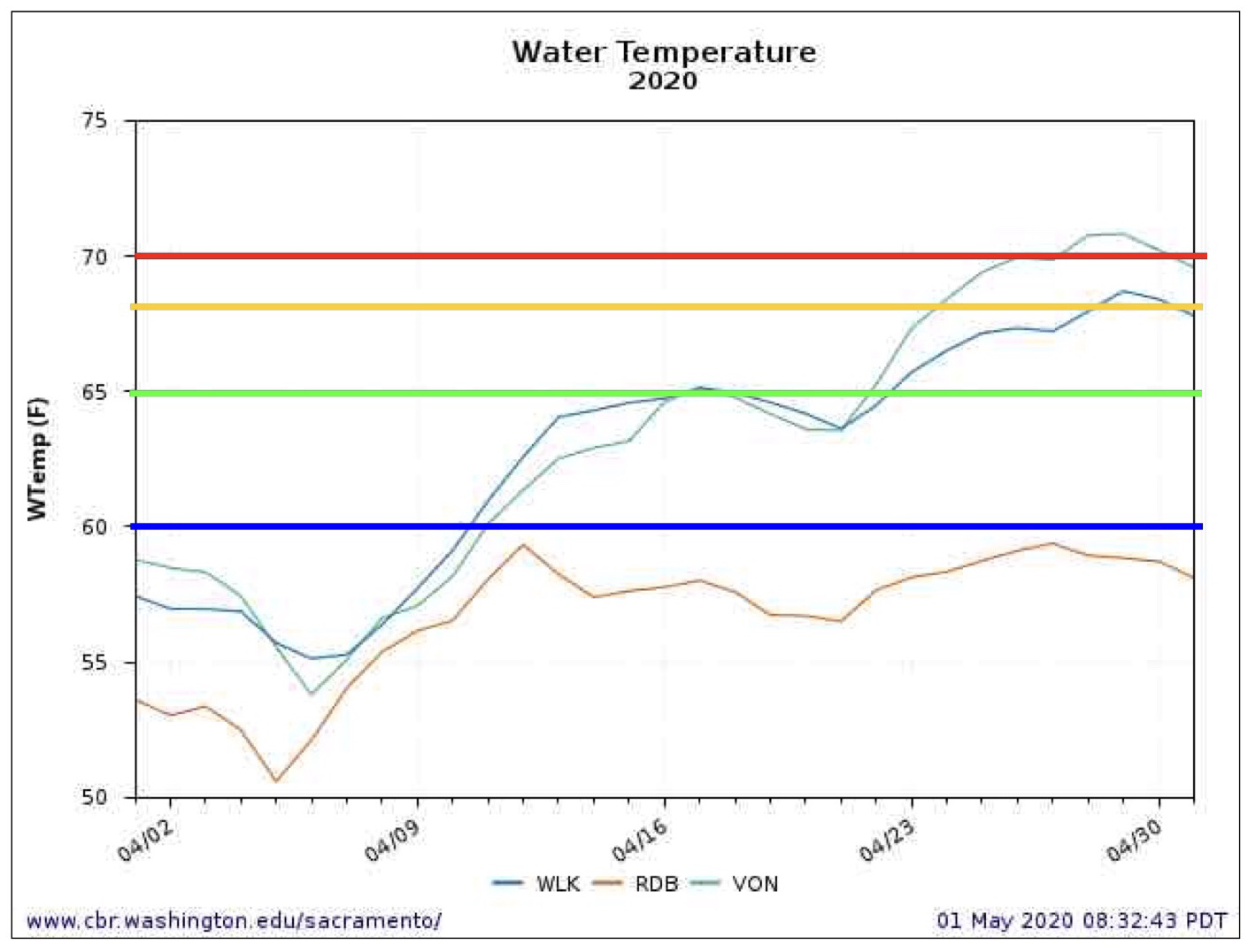

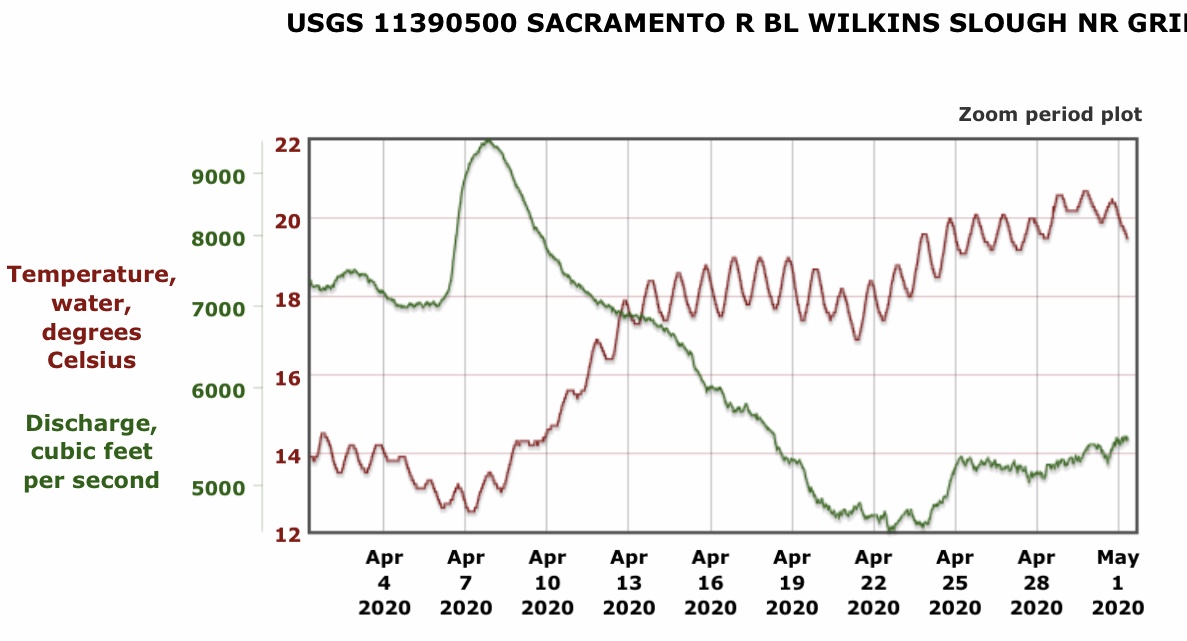

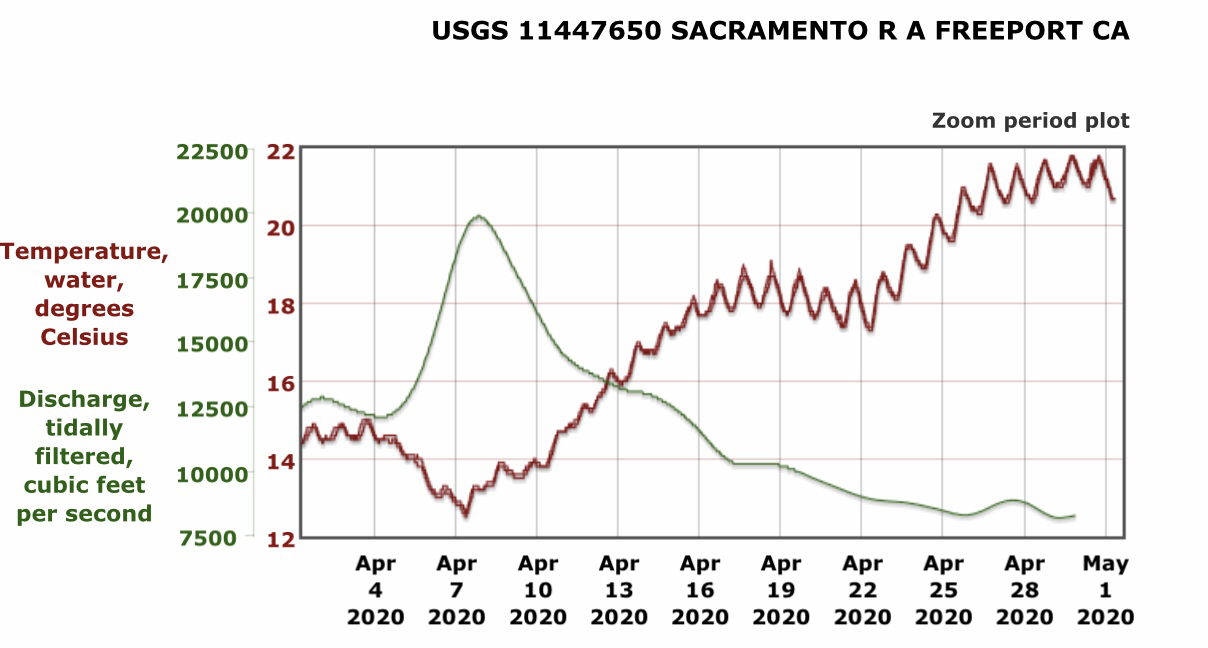

- Reduce exports from the south Delta, especially from March through May.

- Increase San Joaquin River and tributary flows during adult and juvenile migration seasons.

- Improve habitat in spawning, rearing, and migration corridors from spawning reaches to the Bay.

- Capture wild juvenile spring-run below spawning reaches and transport them to the Bay.

- Transport hatchery and wild smolts via barge or floating net pens from lower rivers to the Bay.

So far minimal progress has been made on measures 1-3. As yet, there has been no attempt to address measures 4 and 5 other than pilot studies (encouraging) by the Mokelumne River Fish Hatchery.

“Ironic” is also the wrong word to describe how Delta salvage operations are the least impossible longshot for San Joaquin smolts: it is absolutely infuriating that thirty years of dedicated and talented legal, biological and in-river effort can be undone by the Delta operations that DWR and BOR have just made more efficient at fish killing.

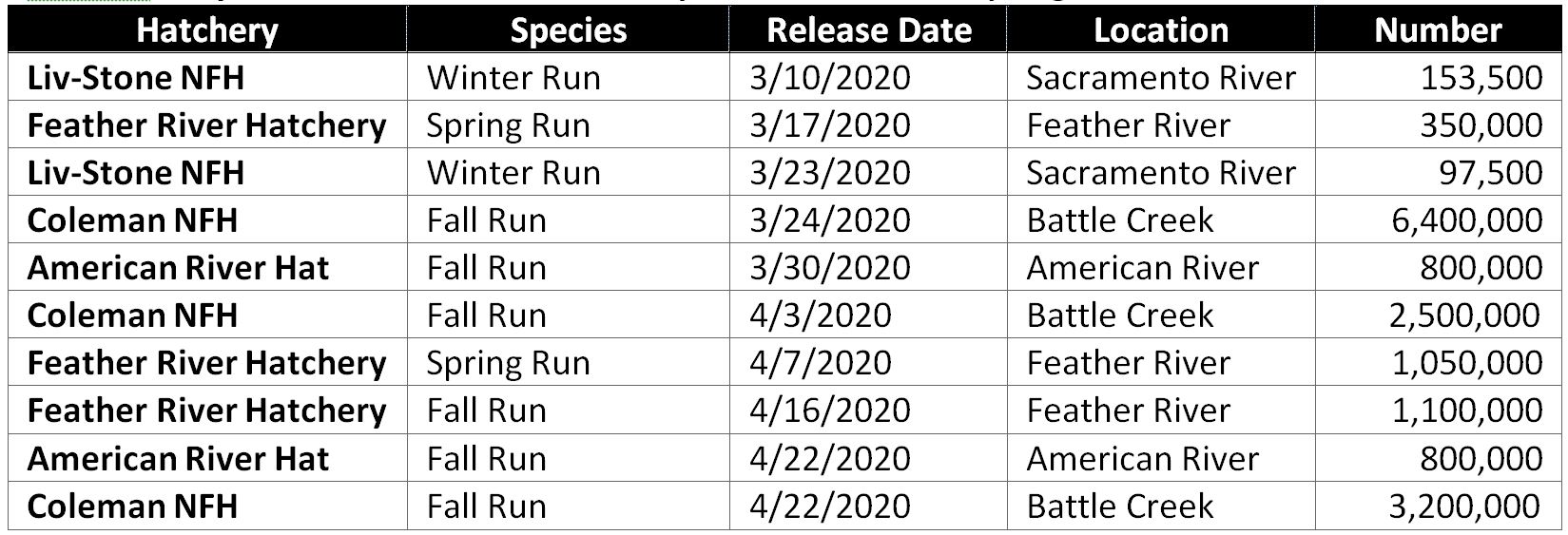

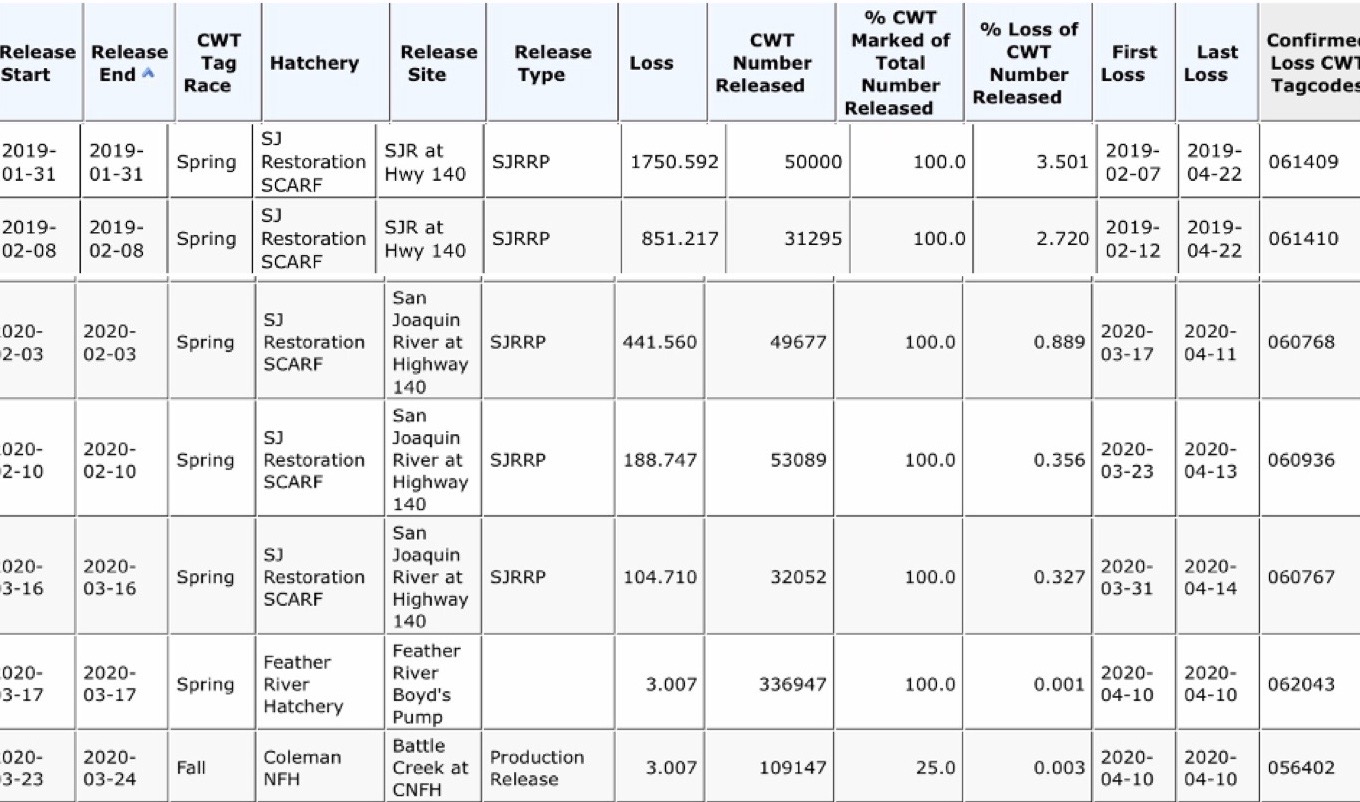

TABLE 1. Comparison of “loss” in Delta salvage facilities between San Joaquin hatchery spring-run smolts and other Central Valley salmon hatchery smolts 2016-2020. Note the word “loss” is used instead of “salvaged” in these tallies. Source: http://www.cbr.washington.edu/sacramento/tmp/deltacwttable_1587318641_393.html Table 1. Continued.

Table 1. Continued.

Figure 1. Hatchery tag adult returns from San Joaquin releases in 2016 (dry San Joaquin water year). Green dots are San Joaquin hatchery spring run released above Merced River in San Joaquin. Blue dots are releases from Merced hatchery fall run released to the Delta near Sherman Island. Orange dots are Mokelumne hatchery fall run released to the Delta near Sherman Island unless specified: GGB = Golden Gate Bridge, HMB = Half Moon Bay on coast, R = Mokelumne River. Data source: https://www.rmpc.org