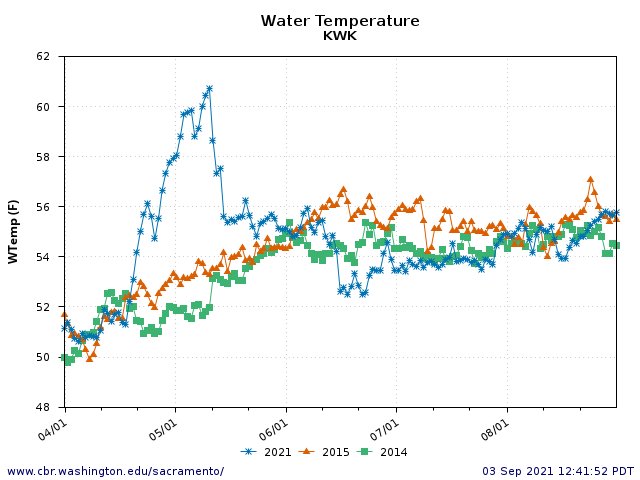

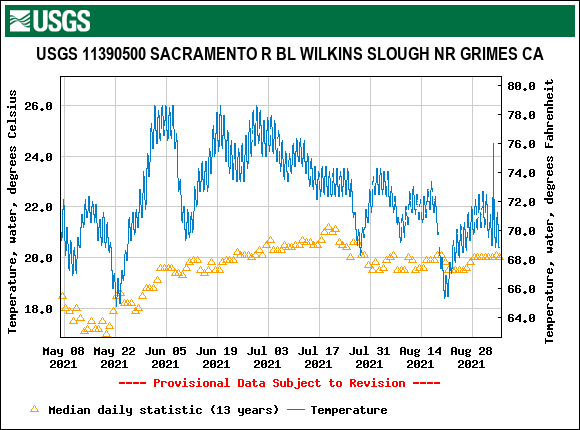

Earlier this summer, the Bureau of Reclamation’s operations of Shasta Reservoir, under its Drought Plan jointly developed with the California Department of Water Resources (DWR), caused high water temperatures that delayed spawning of winter-run Chinook salmon to early summer (mid-June through mid-July).1 Winter-run salmon leave the redds after 2-3 months, which in 2021 will mean a mid-August through September peak emergence.

In their Addendum to the State Water Project and Central Valley Project Drought Contingency Plan issued August 31, 2021, Reclamation and DWR state how an increase in September releases responded to a request from fisheries agencies:

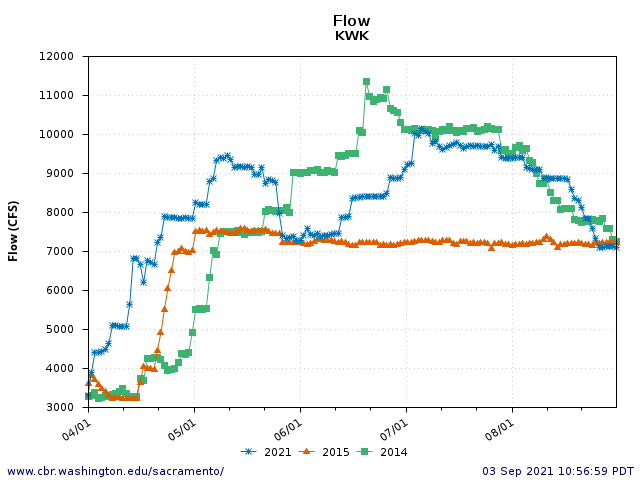

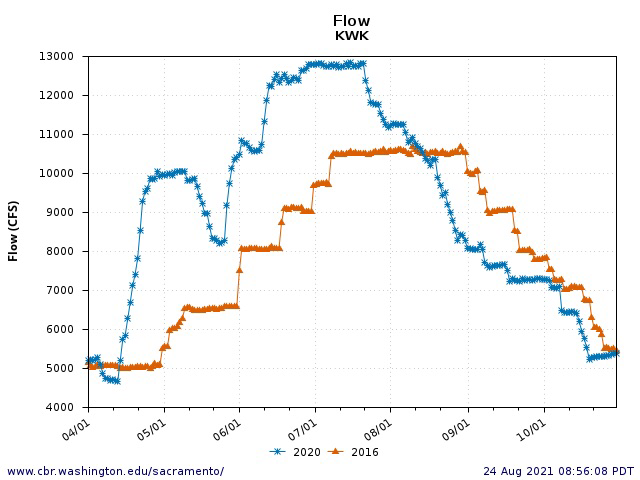

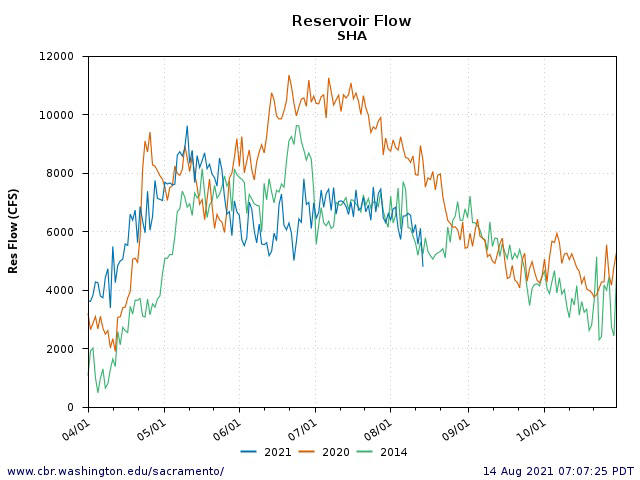

In the July Drought Plan update, Reclamation’s forecast for releases to the Sacramento River were 7,850 cfs in August, ramping down to a monthly average of 5,200 cfs in September, and then going back up to 7,550 cfs in October to move the transfer water referenced above. In late August, the fishery agencies reviewed updated data indicating that a flow of approximately 6,800 cfs was needed through early-October to protect several remaining winter-run Chinook salmon redds. As a result, Reclamation modified its previous plan and held releases at 6,800 starting August 26.

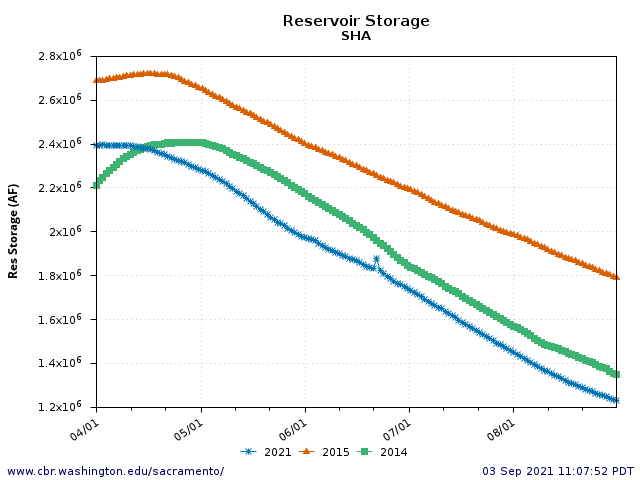

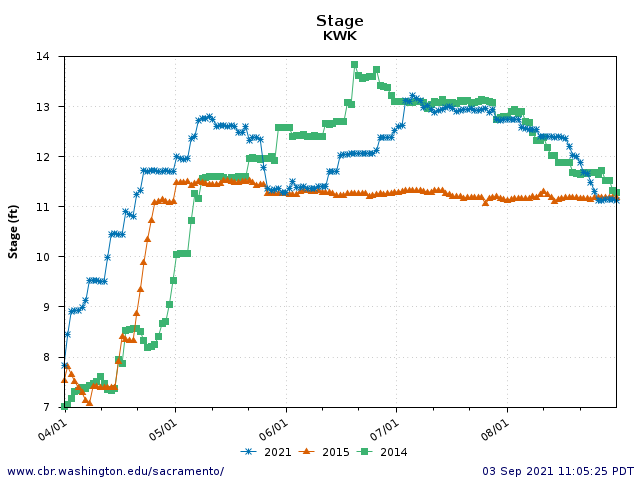

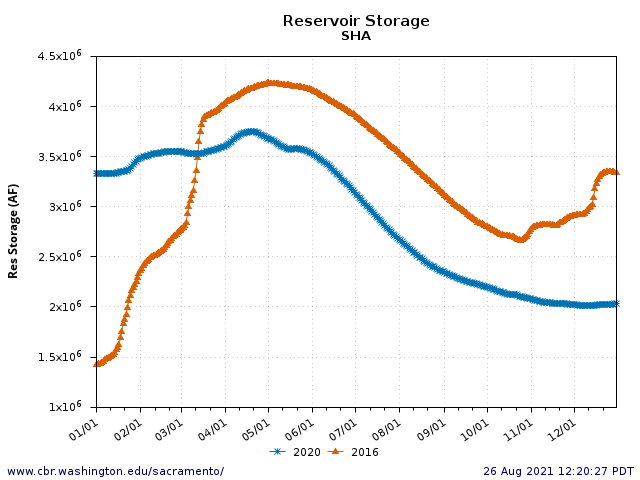

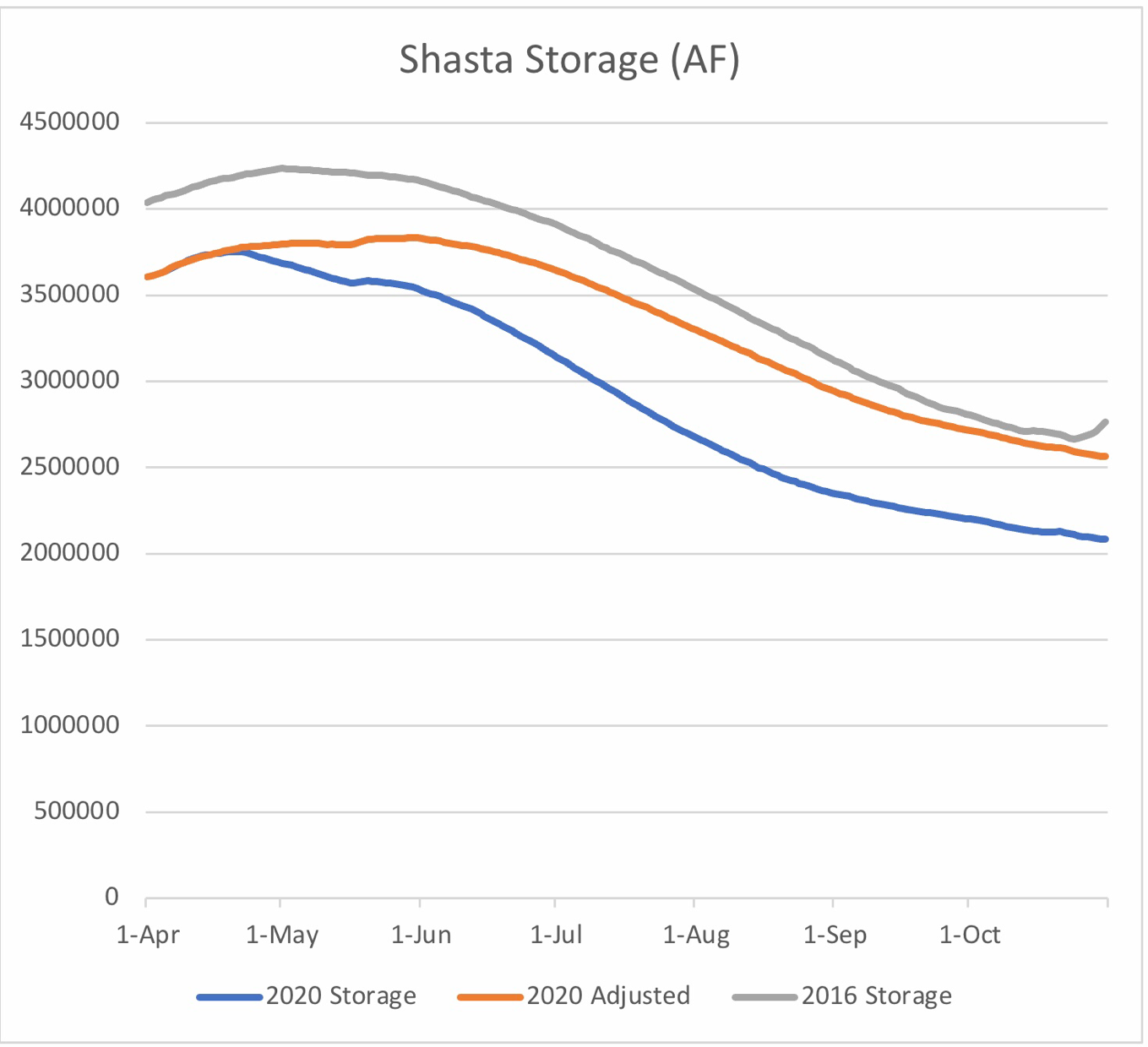

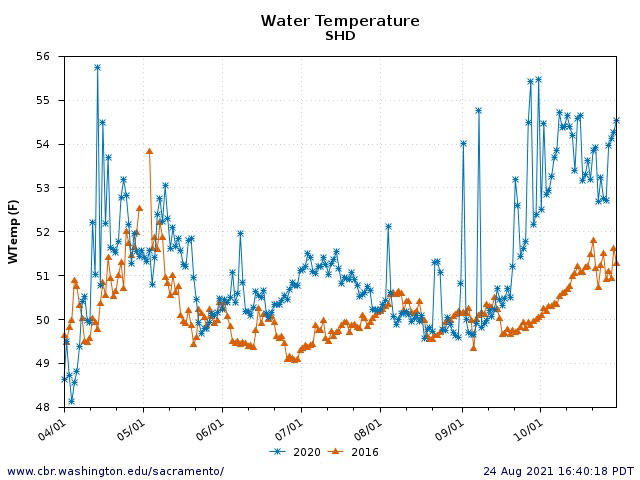

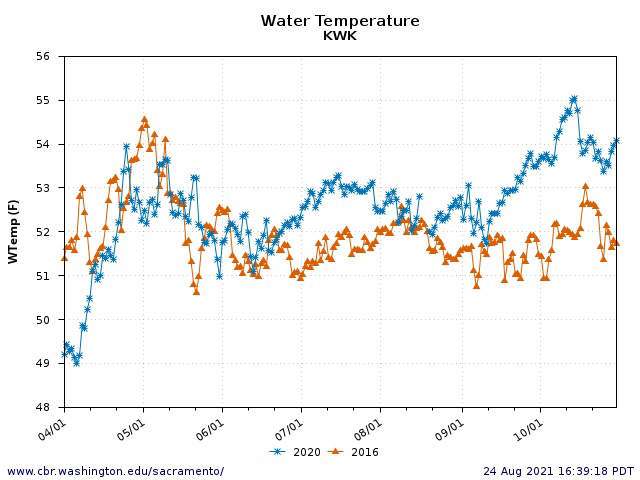

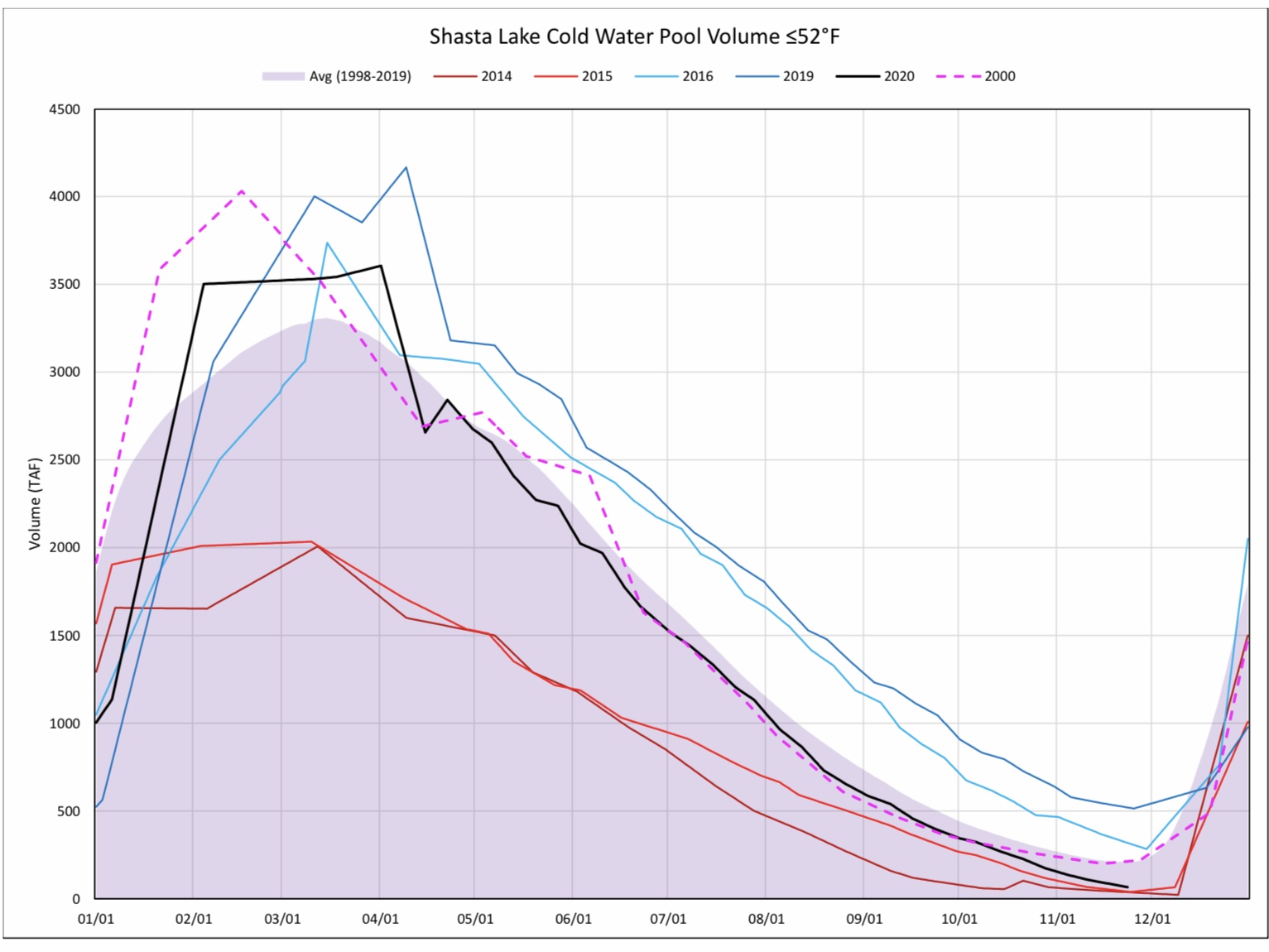

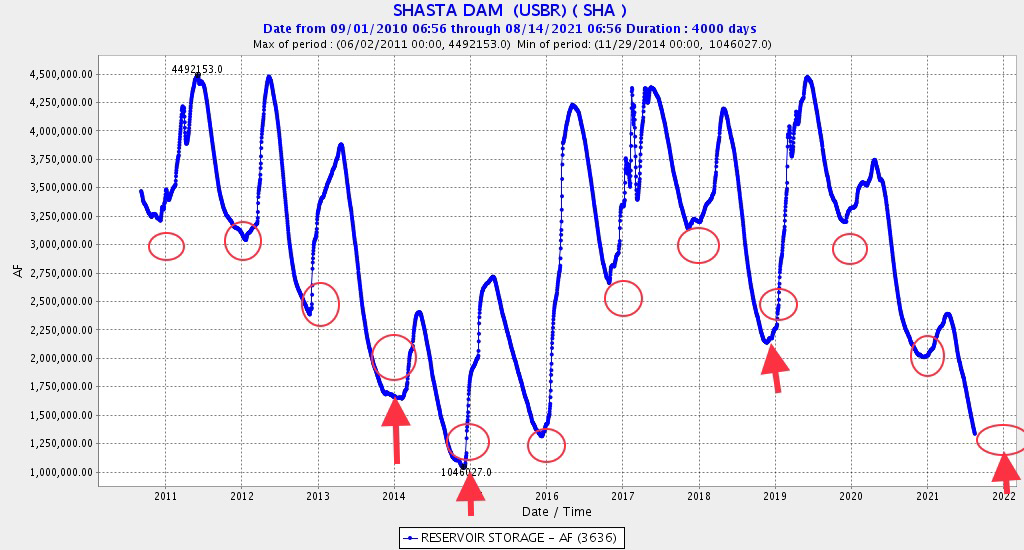

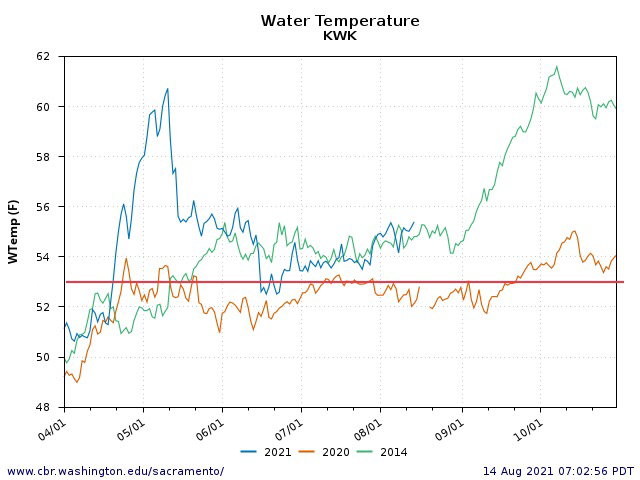

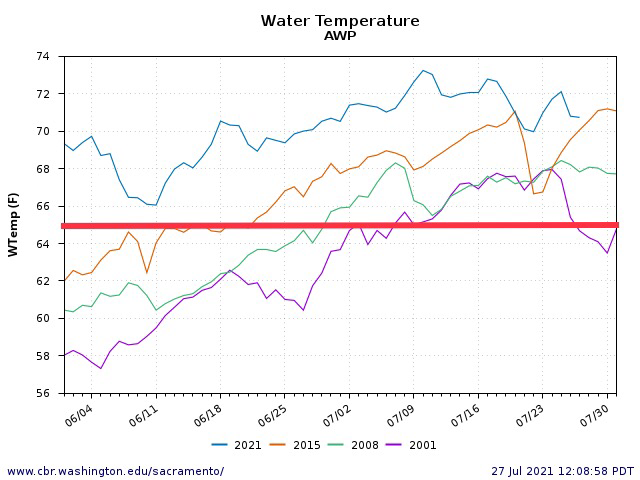

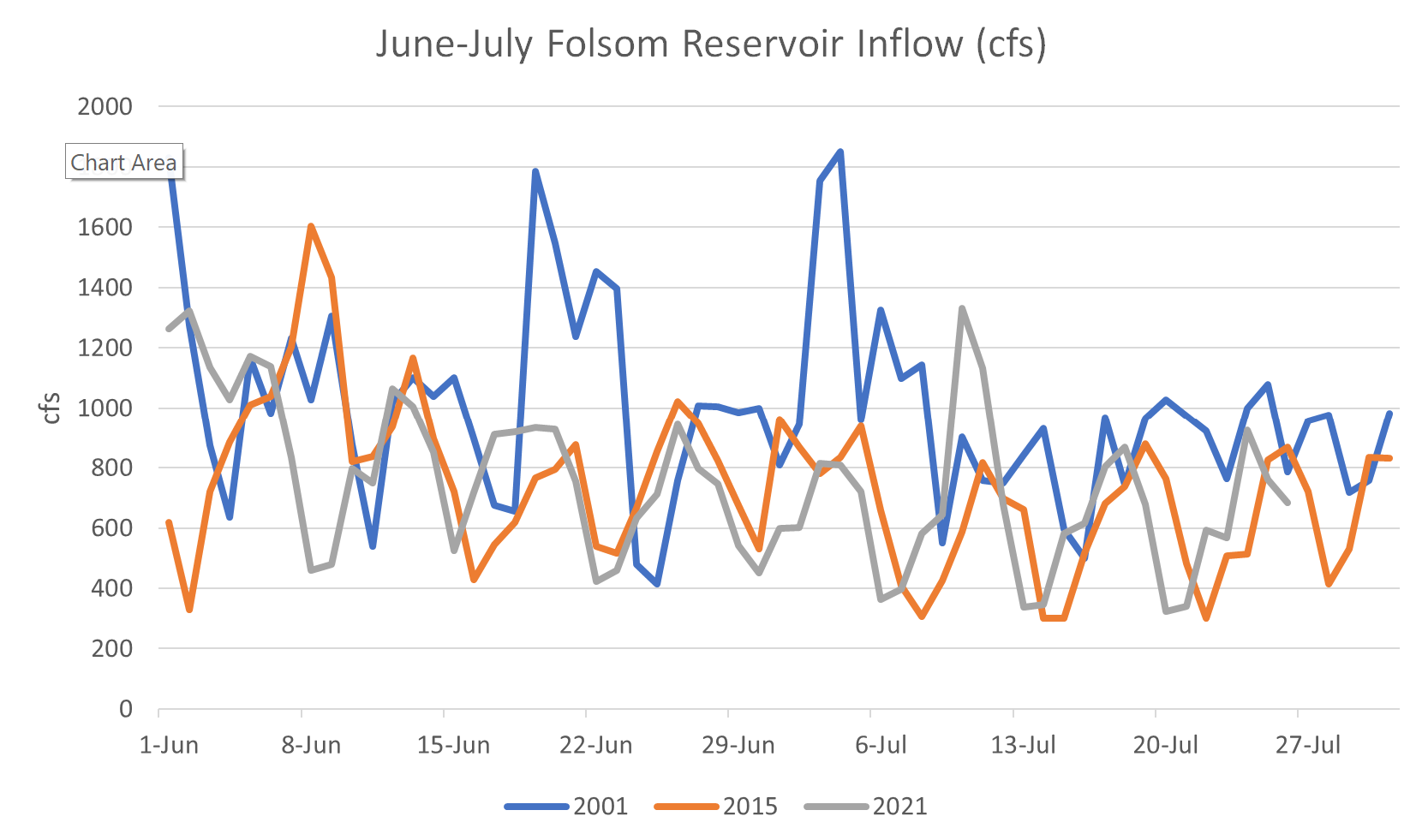

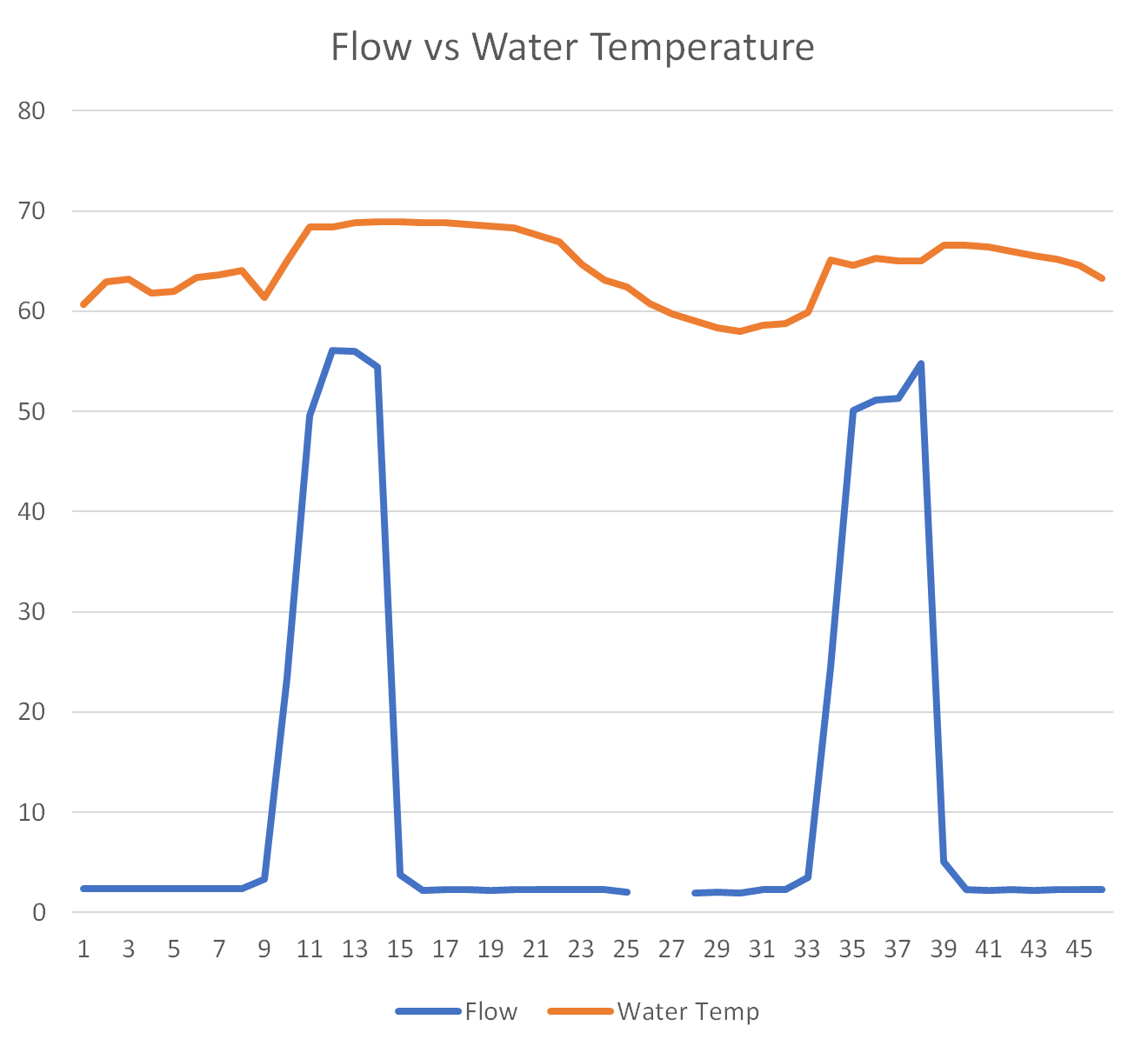

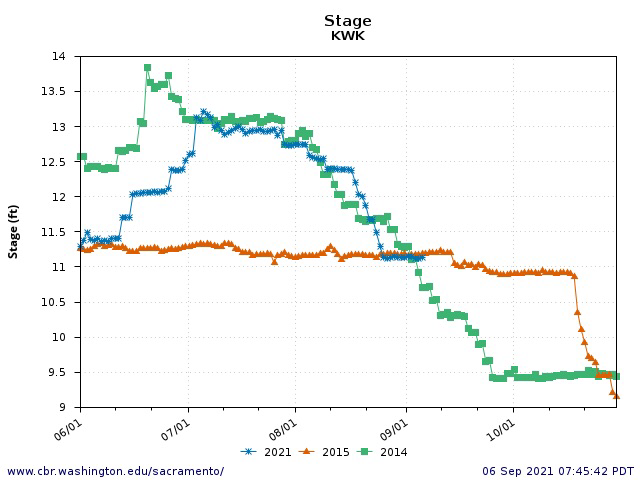

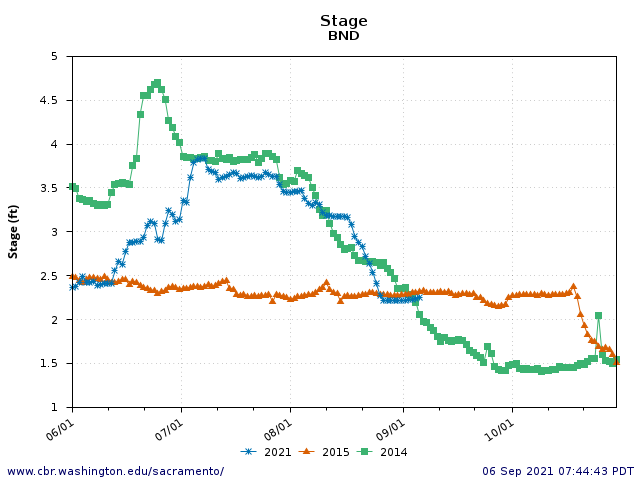

Not so fast. In 2021, as in 2014, Reclamation cast the die early in the year, releasing too much water that was too warm until late June (Figures 1 and 2). That was Reclamation’s call, not the choice of the fish agencies. The agencies know that in drought year 2014, Reclamation also maintained both high flow releases and high water temperatures early in the summer, and that therefore the winter-run salmon spawned late. The agencies also know that a drop the water level 2-3 feet at the beginning of September 2014 (Figures 1 and 2) proved catastrophic to eggs and alevin still in the redds. Such drops in water level, with most redds in 1-3 ft of water, cause dewatering, reduced inter-redd water flow, sedimentation within the redd, lower dissolved oxygen, higher redd water temperatures, early hatching, direct egg/embryo mortality, and restricted fry movement within and emergence from redds.

The planned drop in early September of 2-3 feet in water level, part of the original 2021 Drought Plan, was a bad part of bad plan from the get-go. In 2015, Reclamation at least tried to avoid the drop by keeping releases lower throughout the summer (Figures 1 and 2). The August Addendum insinuates that added loss of storage in September-October to maintain higher flow/stage was the result of fishery agency review, when the agencies never wanted nor originally approved the September drop in river flow. The steady flow/stages in 2015 (Figures 1 and 2) was the appropriate prescription.

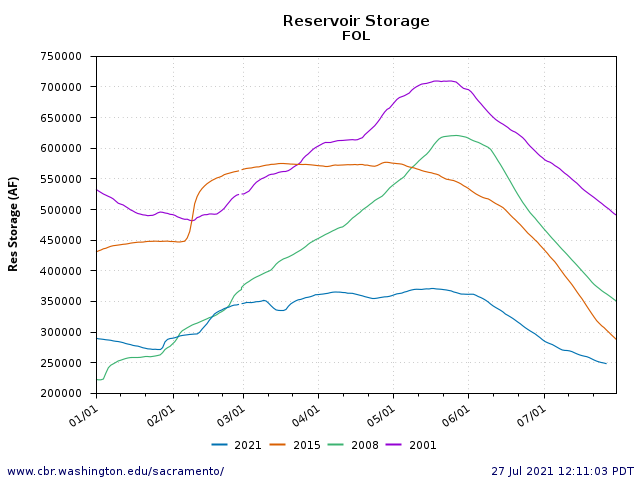

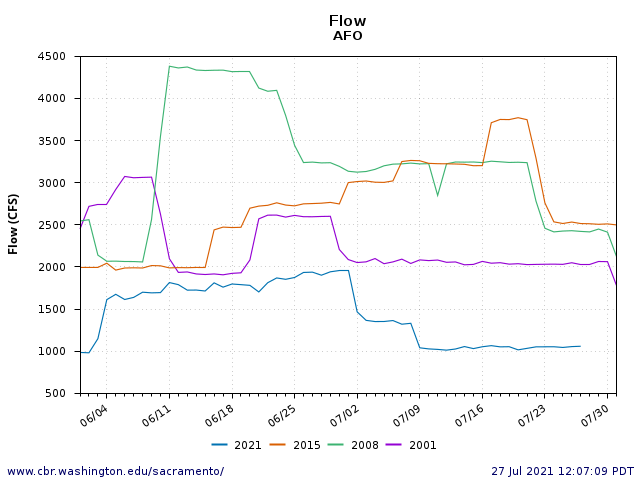

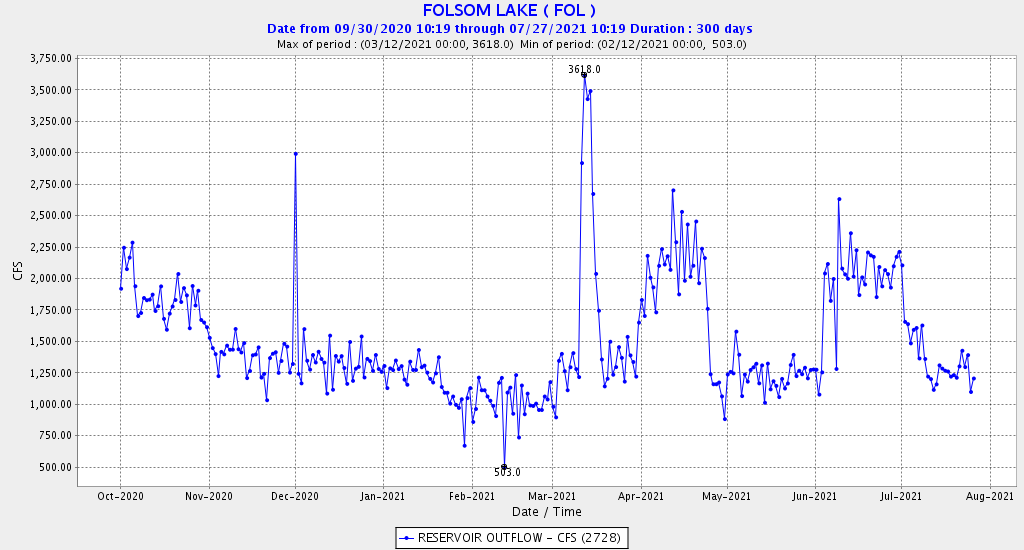

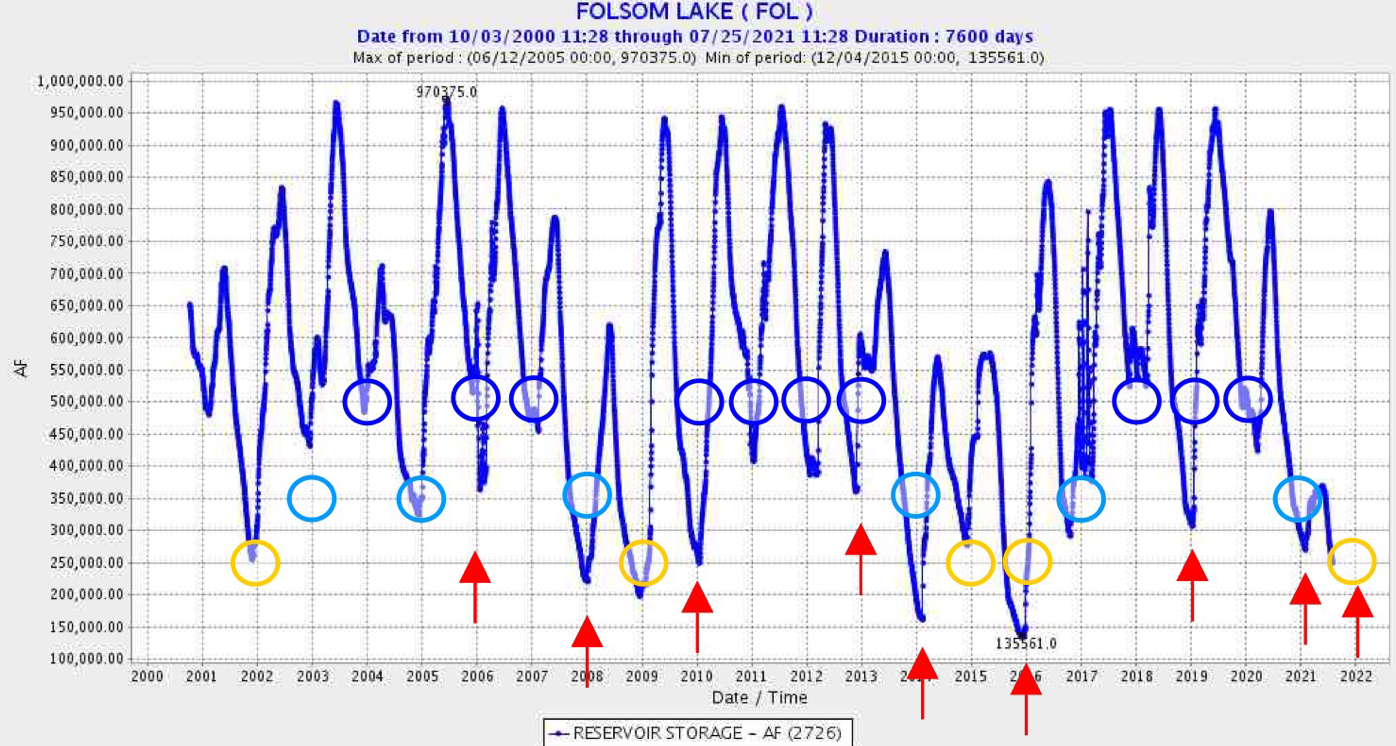

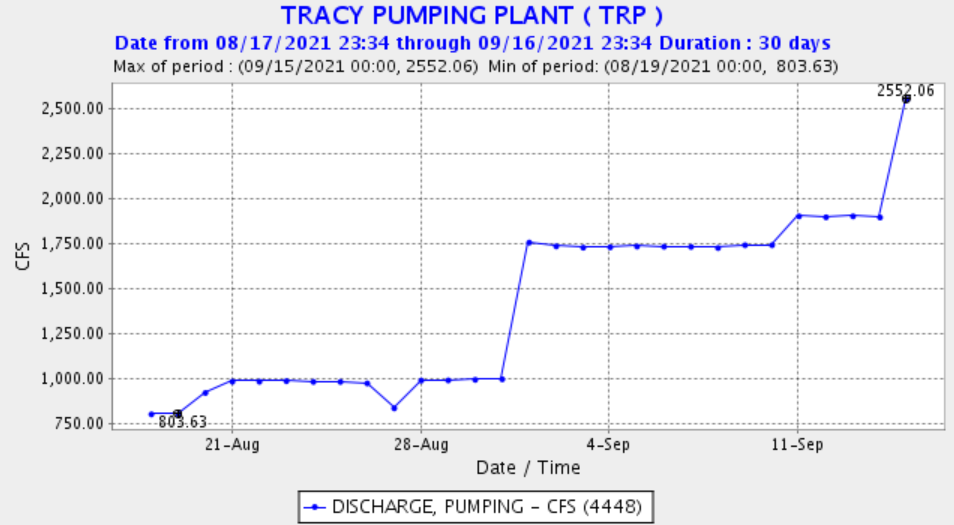

Just as it was a happy circumstance for the Sacramento River Settlement Contractors that Reclamation delivered them too much water north of the Delta early in the year, it was a happy circumstance for Reclamation and the Settlement Contractors that their planned water transfers of about 200 thousand acre-feet (TAF) to buyers south of the Delta just happened to be ready to go just as the drop planned earlier in the summer was scheduled to happen. Transfer water in a market where prices are north of $1000/AF is the mother’s milk of the change in September Shasta operations (Figure 3).

The accelerated schedule of transfers from Shasta storage also reduces the opportunity for the State Water Board or its Executive Director to wake up and smell the receding predictions for the reservoir’s receding shoreline. The tables at the end of the August Addendum now predict end-of-November storage in Shasta to be an unprecedented 729 TAF, down from the July Addendum’s prediction of 849 TAF. The only numbers that have maintained relative consistency throughout the summer 2021 Sacramento River debacle are the levels of deliveries and transfers. That consistency has been matched and enabled by the silence of the Water Board.

In summary, the original 2021 Drought Plan did not address the real risk of redd stranding that proved devastating for the winter-run salmon spawn in summer 2014. The July-August 2021 stage drop was bad enough and should have been avoided, given that high water temperatures delayed the spawn of winter-run to late June. The fish agencies were cornered into choosing between a large September 1 stage drop in a bad original plan and the buy-now-but-pay-later option of maintaining higher flows through September. The additional drain on Shasta storage and Reclamation’s increasing inability to maintain cold water releases through October show the folly and poor design of the original Drought Plan.

This post is part 3 in a series on DWR and Reclamation’s August Addendum to the 2021 Drought Plan.

- Post 1: Addendum to the State Drought Plan — August 31, 2021, Part 1: the Art of the Euphemism

- Post 2: Addendum to the State Drought Plan – August 31, 2021, Part 2: This Is a Test(?)

Figure 1. River stage below Keswick Dam June-October 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 2. River stage at Bend Bridge, 60 miles below Keswick Dam June-October 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 3: Reclamation’s Delta Exports August 15-September 15, 2021.