This is part 2 of a four-part series on the effects of the Shasta-Trinity Division on Sacramento and Trinity-Klamath salmon. Part 1 is an introduction to the series. Part 2 is a discussion of the effects of the Shasta-Trinity Division on Sacramento River salmon.

There are two key points regarding the Winter-Run Chinook Salmon of the Sacramento River in the 2009 NMFS Biological Opinion (BO) that address the long-term operation of the Shasta-Trinity Division:

- “The current status of the affected species is precarious, and future activities and conditions not within the control of Reclamation or DWR are likely to place substantial stress on the species.” It turns out that Reclamation also added a lot of stress that was under their control in both 2014 and 2015 that has put the species under extreme jeopardy.

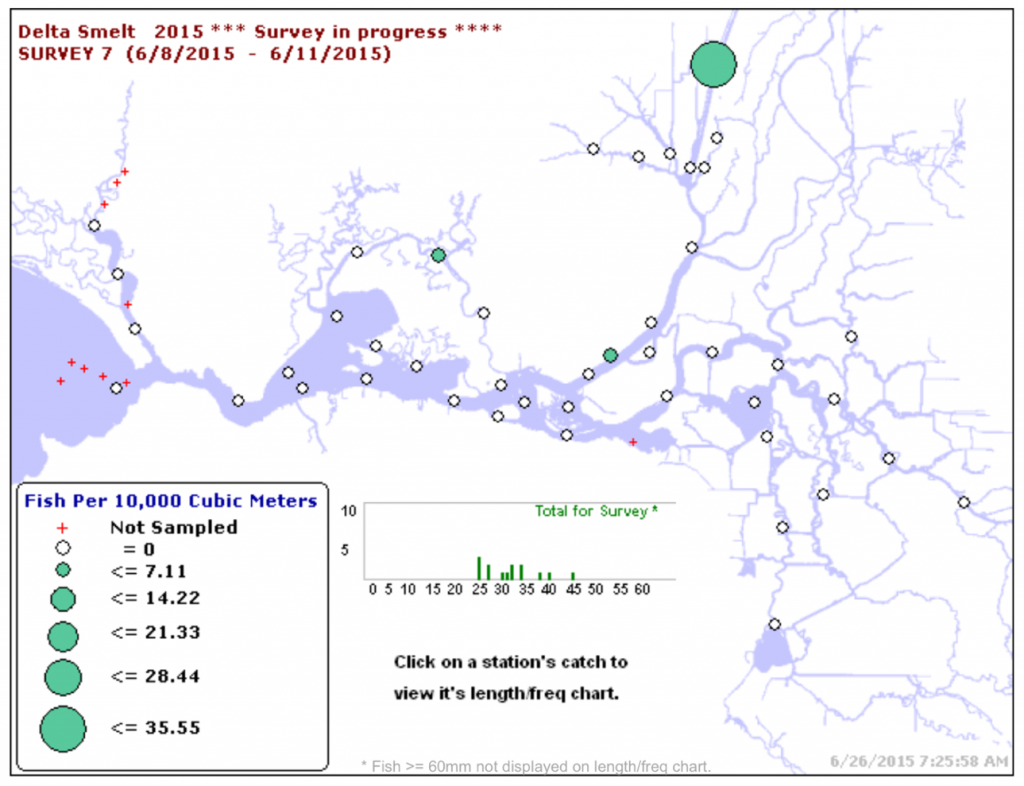

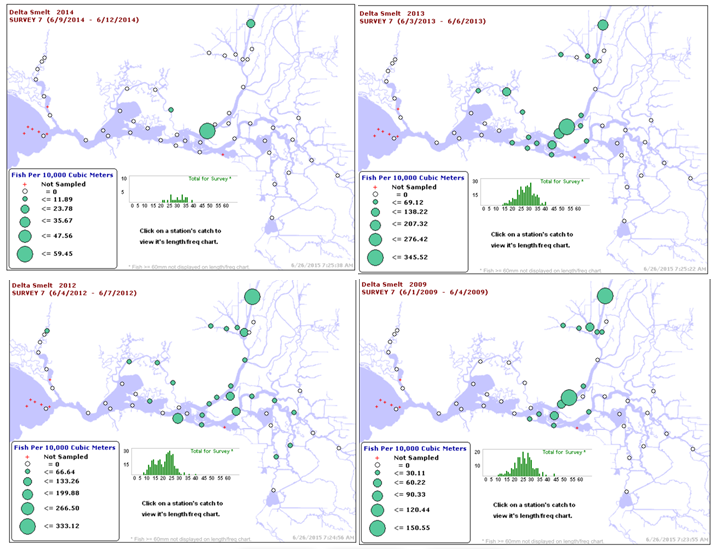

- Simply altering project operations was not sufficient to ensure that the projects were likely to avoid jeopardizing the species or adversely modifying critical habitat. So NMFS prescribed some long term actions (i.e. trap and hauling salmon above Shasta and establishing a Winter Run population in Battle Creek). Because these solutions remain far off, and short-term project operation prescriptions have been entirely ineffective in sustaining the population in the interim, the Winter Run population is in dire straits.

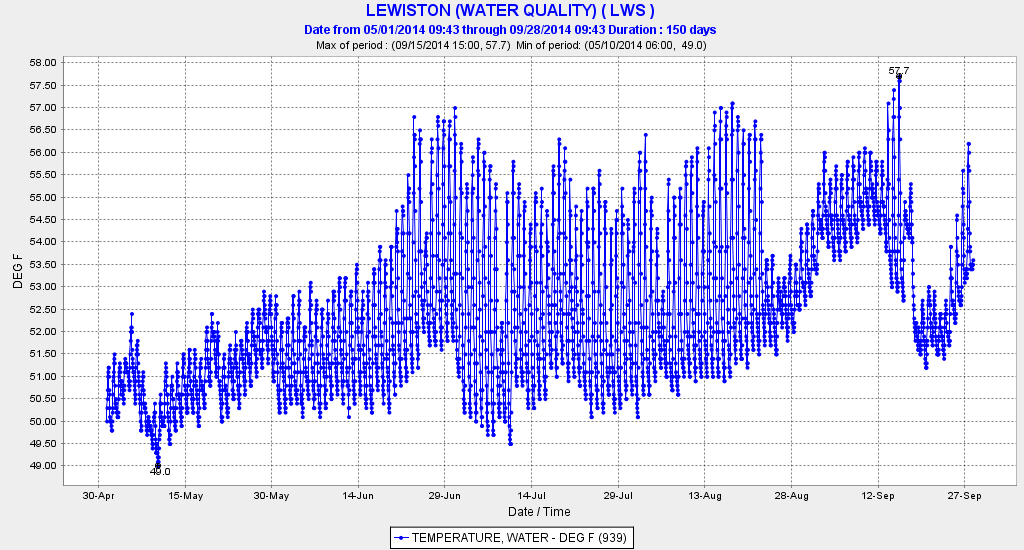

NMFS’s near-term measures prescribed in the BO focused on providing suitable water temperatures in the Sacramento River below Shasta in a high percentage of years. The BO prescribed fewer and fewer protections in the drier years with poorer and poorer spawning and rearing habitat near Redding, reaching an unintended consequence of little or no viable habitat left in late summer 2014 and sub-marginal habitat through the summer of 2015. NMFS blamed poor reservoir temperature modeling and forecasting by Reclamation in both years. In reality, problems in both years could have been avoided.

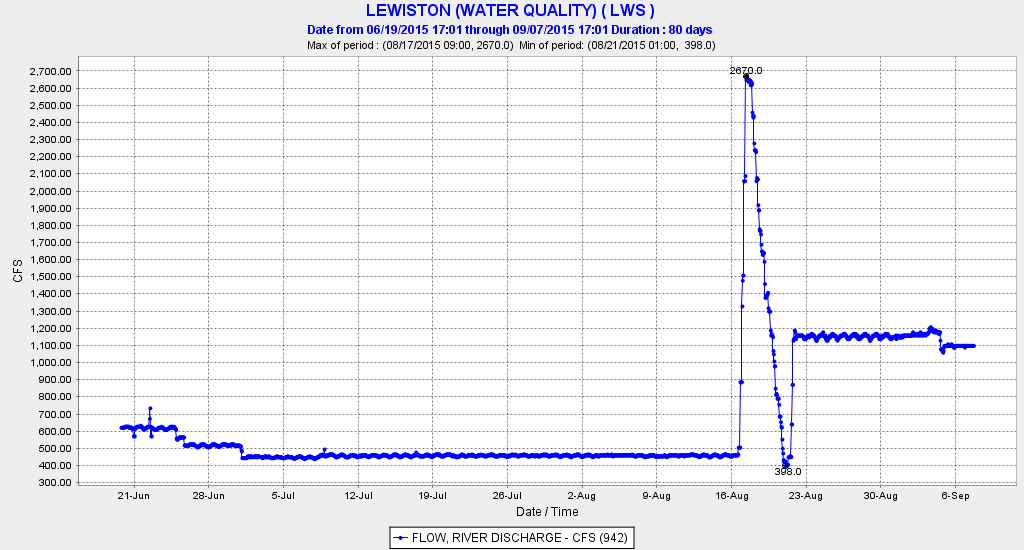

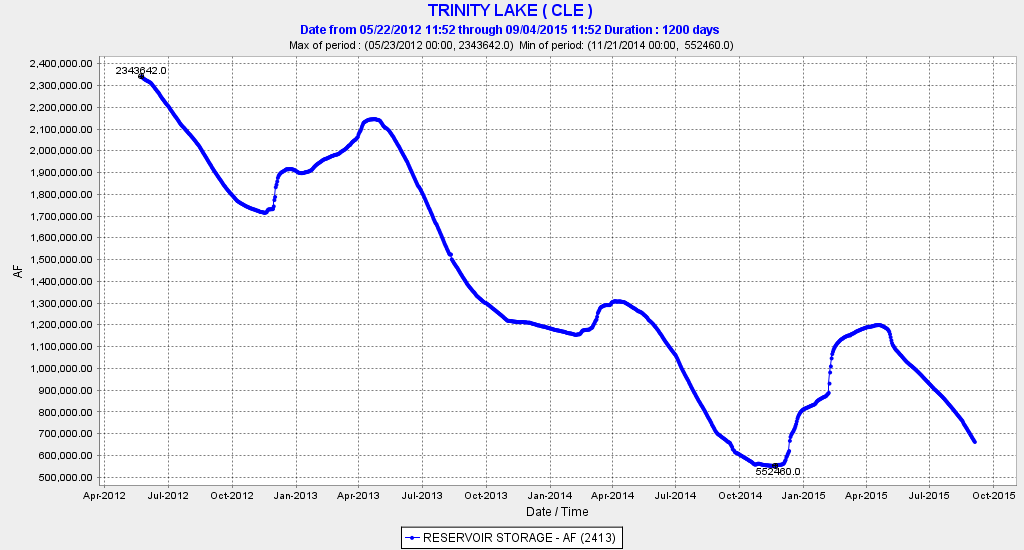

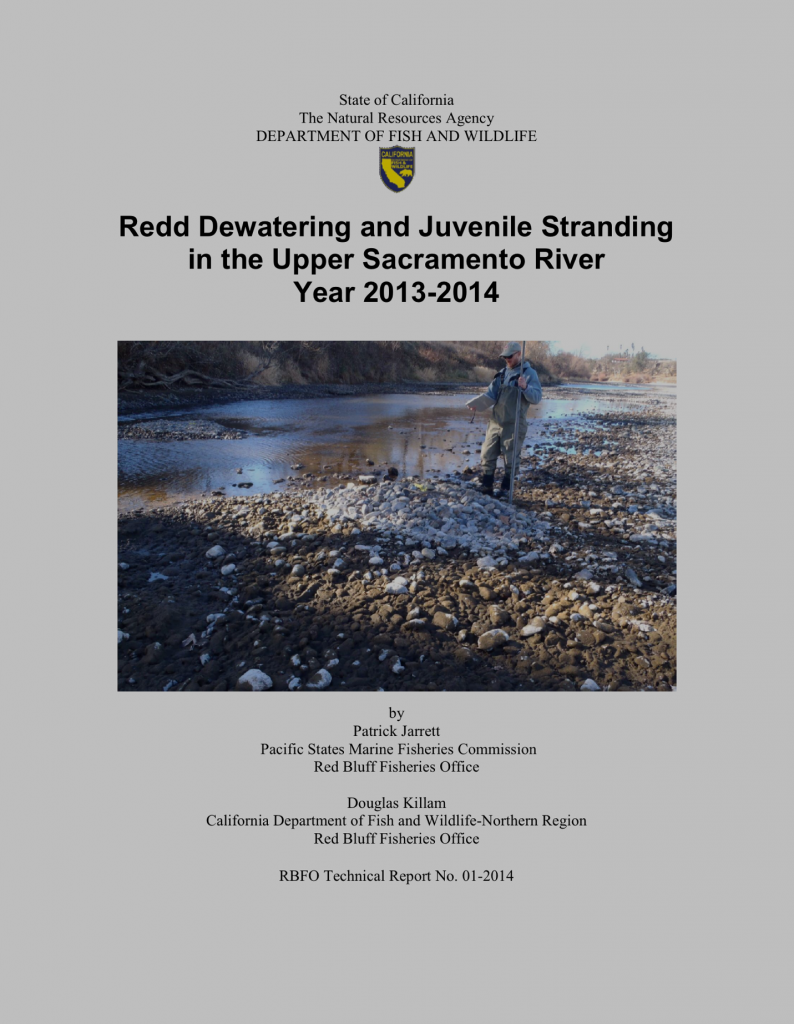

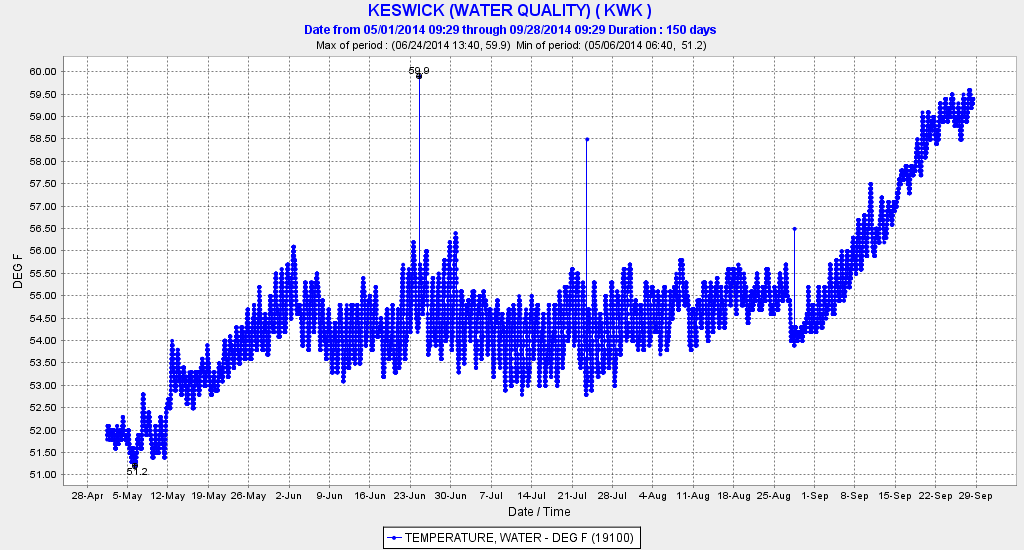

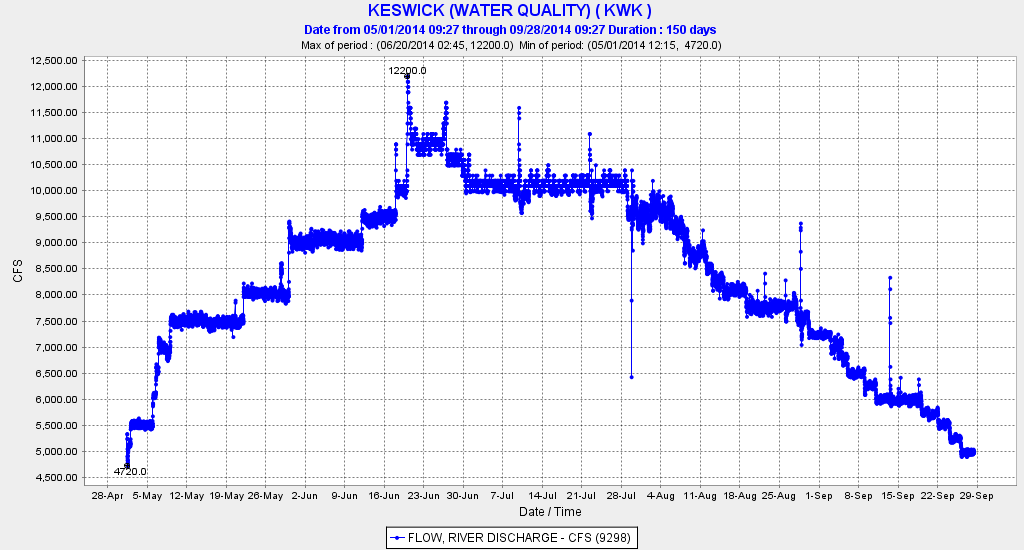

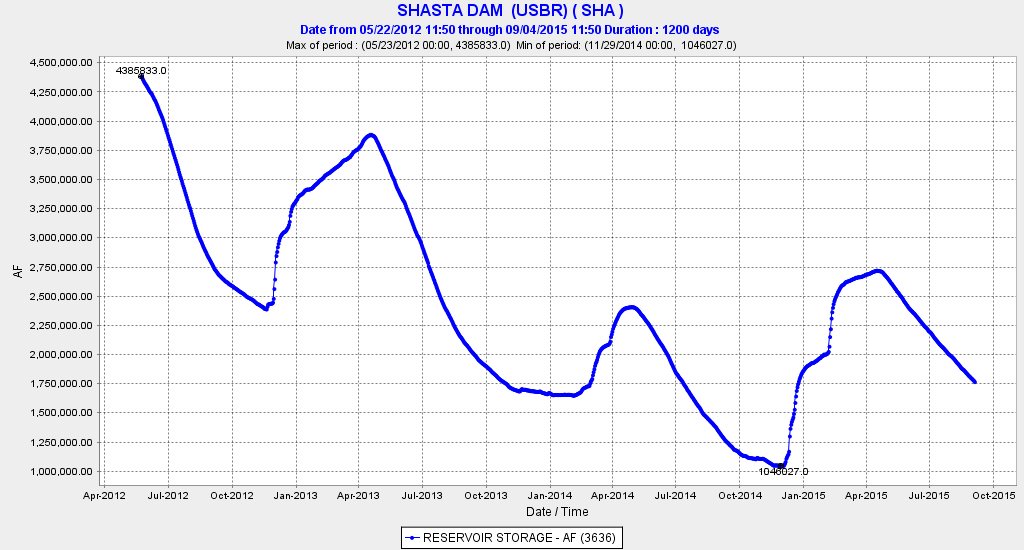

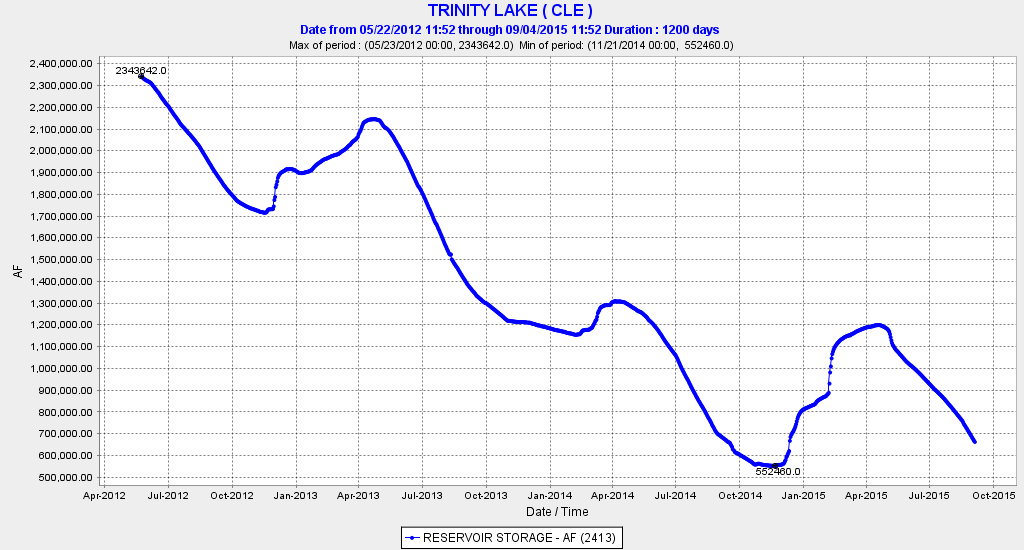

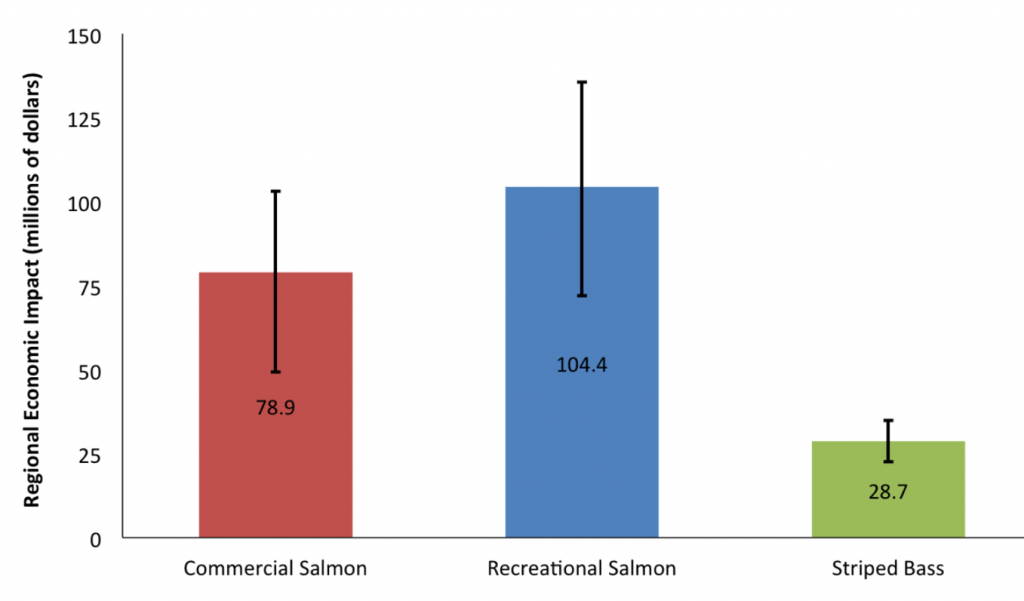

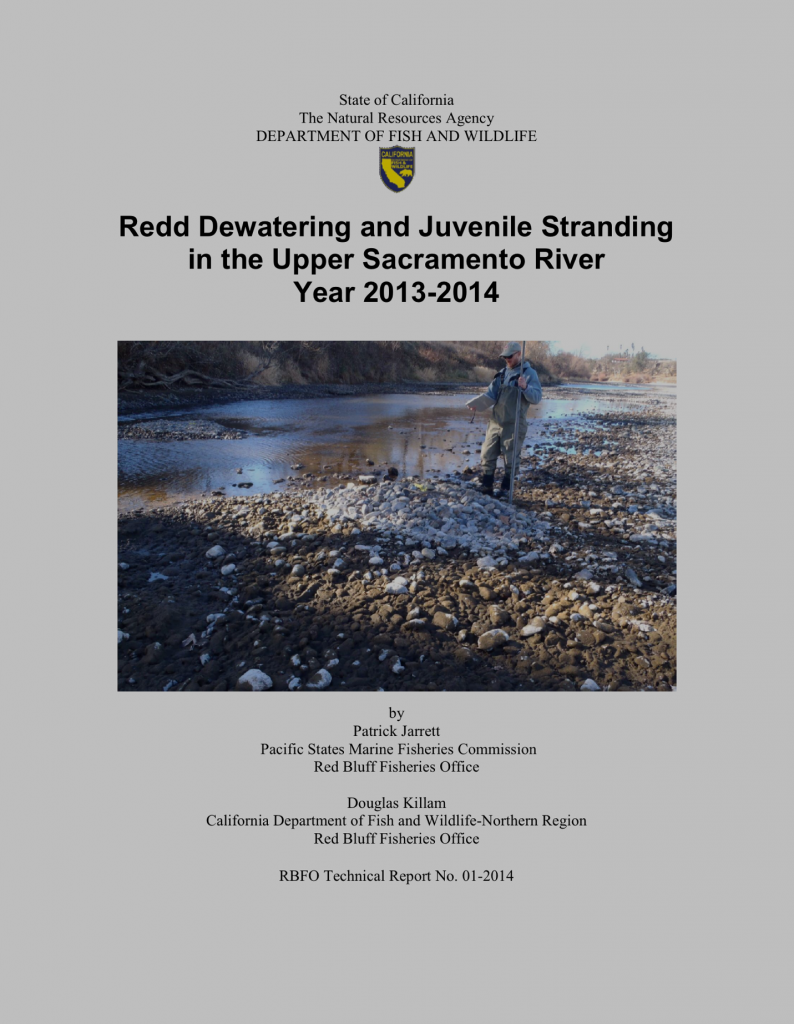

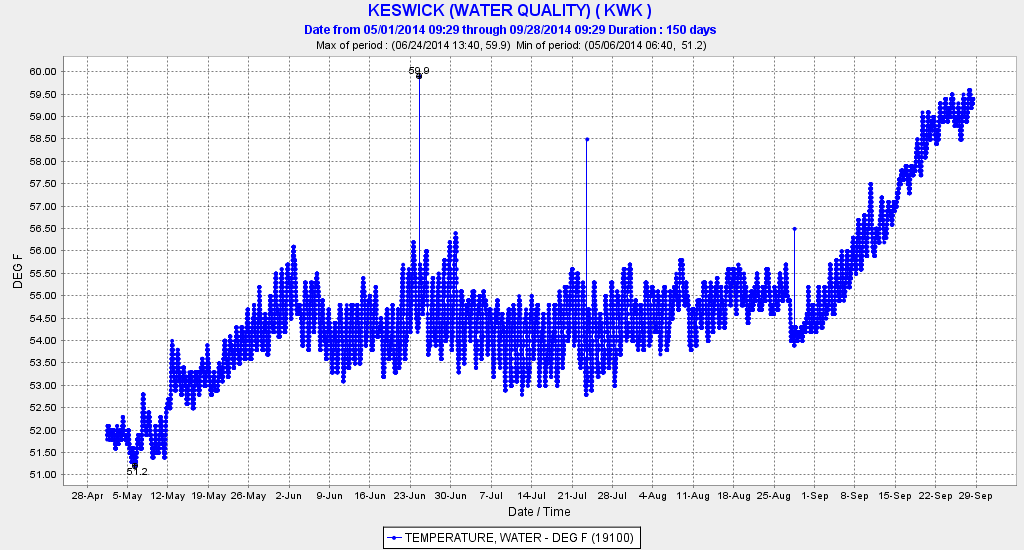

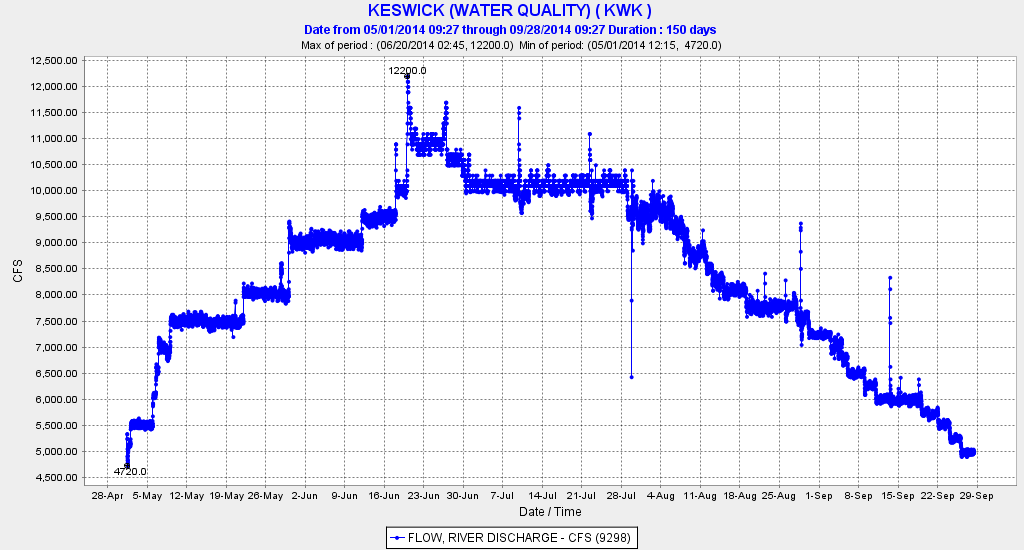

The basic problem in 2014 and 2015 was that the operation of the Shasta-Trinity Division resulted in elevated water temperatures that had lethal and sub-lethal effects on egg incubation and juvenile emergence in the upper Sacramento River. Their excuse: “The immediate operational cause was lack of sufficient cold water in storage to allow for cold water releases to reduce downstream temperatures at critical times and meet other project demands.” The real problem was defective forecasting tools and over-allocation of water to contractors during the third and fourth years of the drought. The lethal outcome was also not only the result of high water temperatures, but also of redd stranding from flow reductions (see figure below).

CDFW Report on stranding mortality of salmon eggs and alevins in the Sacramento River in late summer 2014. It is obvious from the report’s cover photo that the problem was not just water temperature.

NMFS’s “Reasonable and Prudent Alternative (RPA)” in its Biological Opinion

“NMFS made many attempts through the iterative consultation process to avoid developing RPA actions that would result in high water costs, while still providing for the survival and recovery of listed species. … We will seek to incorporate this new science as it becomes available through the adaptive management processes embedded in the RPA.” The RPA requires Reclamation to seek higher water costs (more water for salmon) from the State Water Resources Control Board in extreme conditions. But in 2014 and 2015, Reclamation instead asked the State Board for the opposite: contracted deliveries to senior water contractors at the expense of the fish, with a simultaneous weakening of water quality standards for flow and water temperature. The Board granted Reclamation’s request, with NMFS’s “concurrence.” In both its Biological Opinion and in real time decision making, NMFS limited water costs but failed to protect the species. A Biological Opinion can only work when a regulated entity follows it and a regulator enforces it.

RPA Action 1.1.4

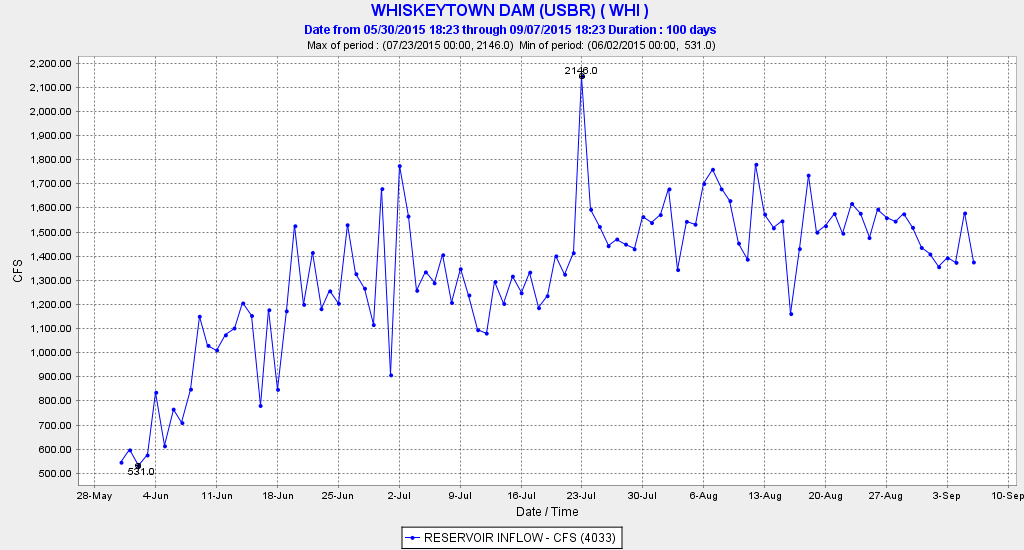

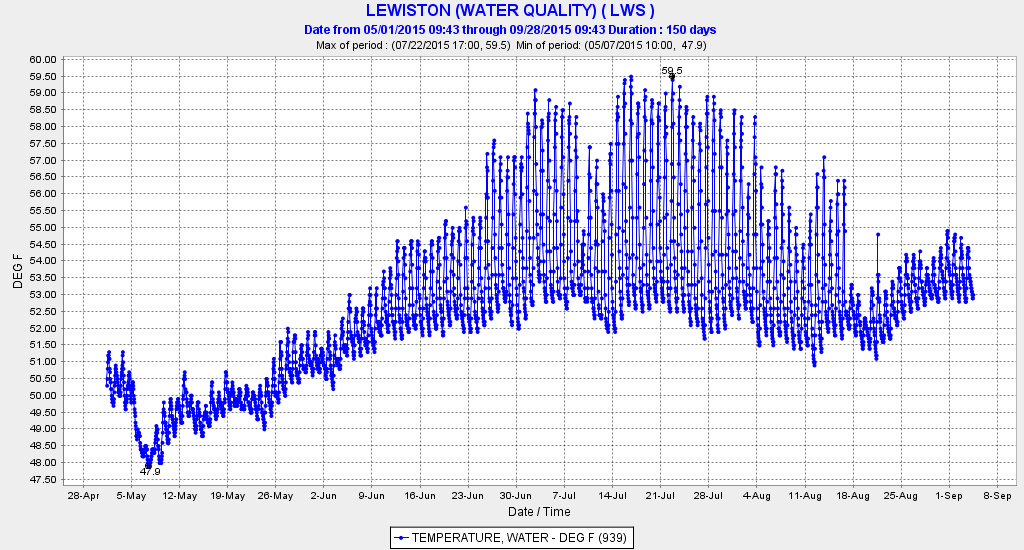

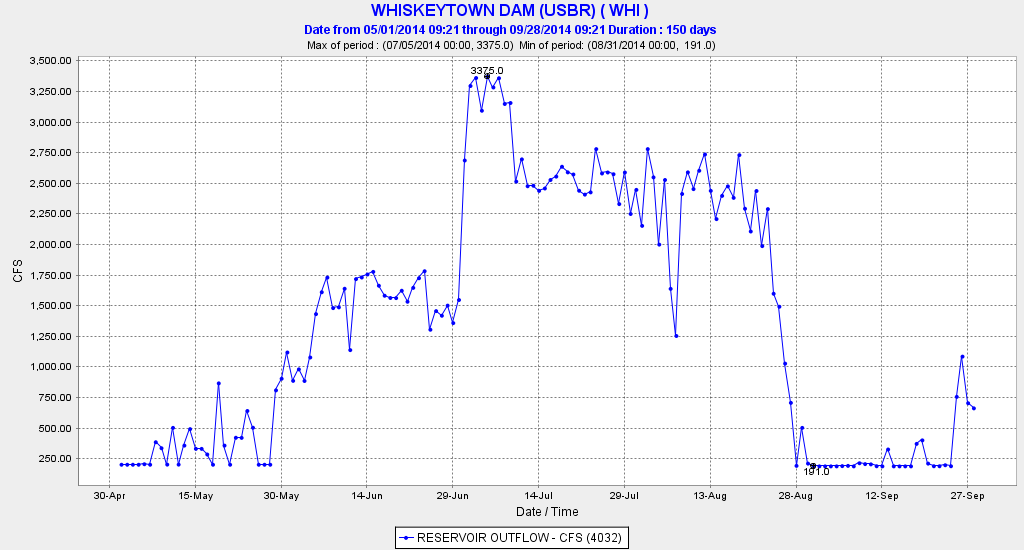

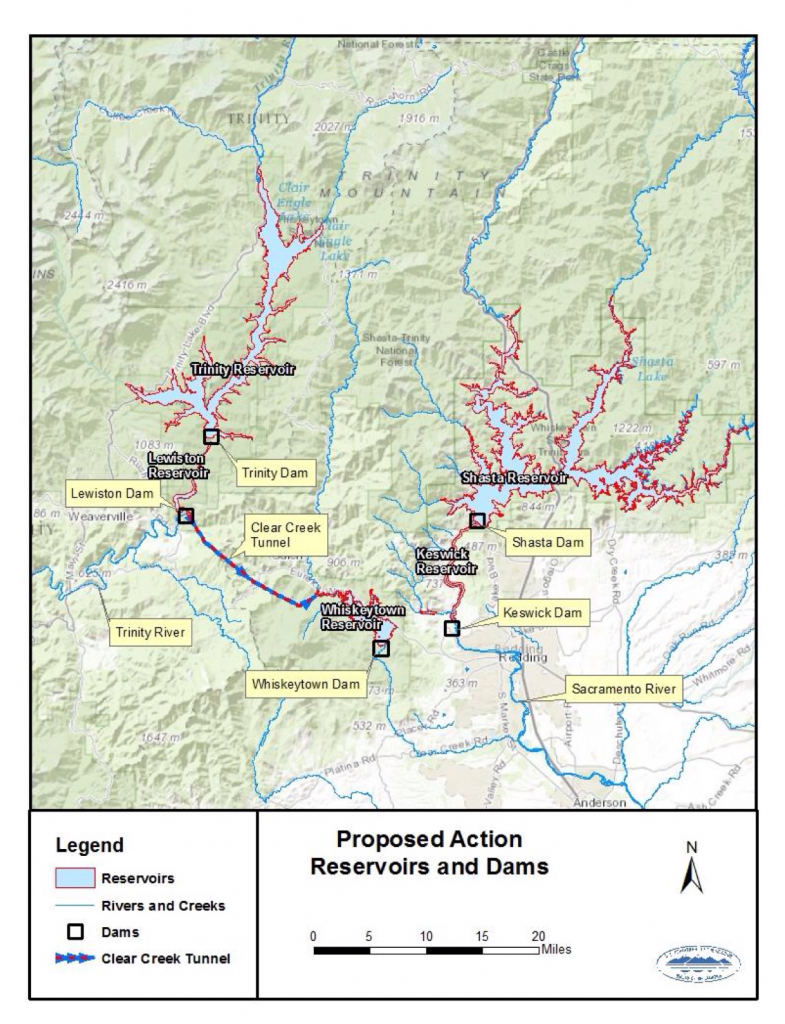

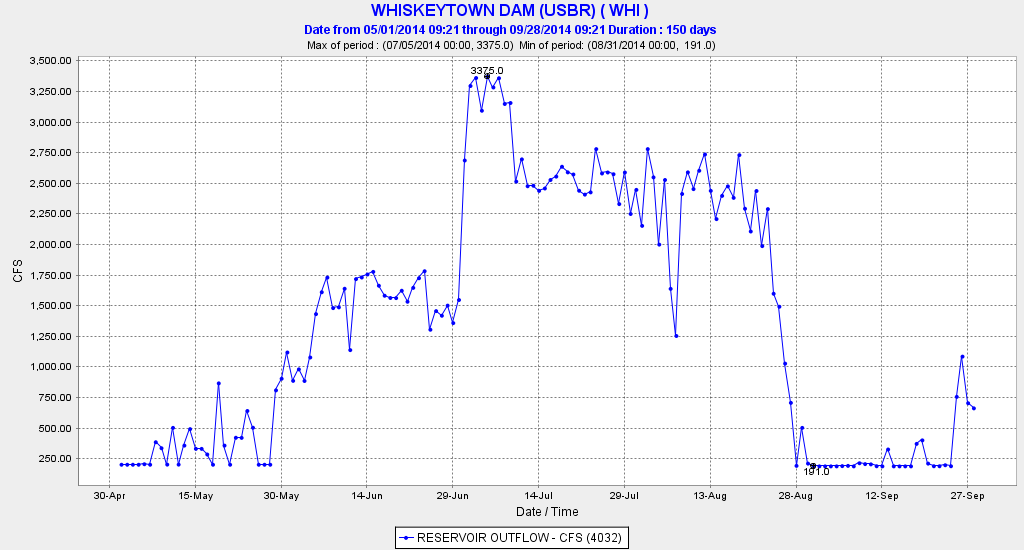

The RPA included Action I.1.4, Spring Creek Temperature Control Curtain Replacement. The curtain in Whiskeytown Reservoir at the inlet to the Spring Creek Powerhouse on Keswick Reservoir was replaced in 2011; however, the curtain was minimally effective in cooling water transferred to the Sacramento River from Trinity Reservoir. Large volumes of Shasta cold-water pool (50°F) had to be released into Keswick Reservoir to cool warmer (58-59°F) Spring Creek Powerhouse releases to keep releases to the Sacramento River at the required 54-56°F.

RPA Action Suite 1

The RPA also includes a suite of actions for operating the Shasta-Trinity Division.

- “Ensure a sufficient cold water pool to provide suitable temperatures for winter-run spawning between Balls Ferry and Bend Bridge in most years, without sacrificing the potential for cold water management in a subsequent year. Additional actions to those in the 2004 CVP/SWP operations Opinion are needed, due to increased vulnerability of the population to temperature effects attributable to changes in Trinity River ROD operations, projected climate change hydrology, and increased water demands in the Sacramento River system.” In 2014 and 2015 water temperatures downstream of Redding, including the reach between Balls Ferry and Bend Bridge, were lethal to Winter Run eggs and alevins. The NMFS BO and in particular this RPA action suite were simply not followed. Instead, NMFS “concurred” with relaxing the water quality standards that resulted in objectives not being met.

- “Ensure suitable spring-run temperature regimes, especially in September and October. Suitable spring-run temperatures will also partially minimize temperature effects to naturally-spawning, non-listed Sacramento River fall-run.” Fall temperatures in the Sacramento River for Spring Run salmon were also lethal in 2014. It is unclear at present whether sufficient cold-water pool will be available in the fall of 2015 to prevent a repeat of 2014.

RPA Action 1.2.4

May 15 through October Keswick Release Schedule (Summer Action)

- “Reclamation shall develop and implement an annual Temperature Management Plan by May 15 to manage the cold water supply within Shasta Reservoir and make cold water releases from Shasta Reservoir and Spring Creek to provide suitable temperatures for listed species, and, when feasible, fall-run.” The 2014 and 2015 plans proved faulty in their forecasts for sustaining the cold water pool in Shasta, and thus this requirement was not met even in the 9 mile reach of the Sacramento River immediately downstream of Keswick Reservoir.

- “Reclamation shall manage operations to achieve daily average water temperatures in the Sacramento River between Keswick Dam and Bend Bridge as follows: Not in excess of 56°F at compliance locations between Balls Ferry and Bend Bridge from May 15 through September 30 for protection of winter-run, and not in excess of 56°F at the same compliance locations between Balls Ferry and Bend Bridge from October 1 through October 31 for protection of mainstem spring run, whenever possible.” Reclamation, the State Board, and NMFS found maintaining these objectives impossible in 2014 and 2015.

Unable to meet temperature requirements, Reclamation and NMFS are seeking “other solutions”:

- Expansion of the Livingston Stone National Fish Hatchery production for Winter-Run from the typical broodstock of 120 adults to accommodate up to 400 adults.

- Restrictions on recreational and commercial fishing to benefit of Winter-Run salmon.

- The agencies will continue to actively investigate other project elements that make sense, including:

- applying reflective paint or other shading on the penstocks into Whiskeytown Reservoir

- accelerating acquisitions related to the installation of the Oak Bottom Temperature Curtain in Whiskeytown Reservoir,

- decreasing the exposure of cold water from Trinity to sunlight as it travels through the powerhouse and exposed pipes that to help ensure this cold water remains cold.

- continue to seek input from stakeholders to develop other non-flow actions that may help minimize overall impacts (e.g. , predation control strategies and/or restoration, hatchery, etc.)

The demise of 2014 Winter Run brood year has been attributed to high water temperature in the Sacramento River below Keswick Reservoir in late summer 2014.

Another contributing factor to the 2014 brood year demise was high flows during spawning (June-July) followed by low flows at emergence (September).

The reduction in inflow from the Trinity in 2014 contributed to Winter Run redd dewatering and higher water temperatures in the Sacramento River near Redding in 2014.