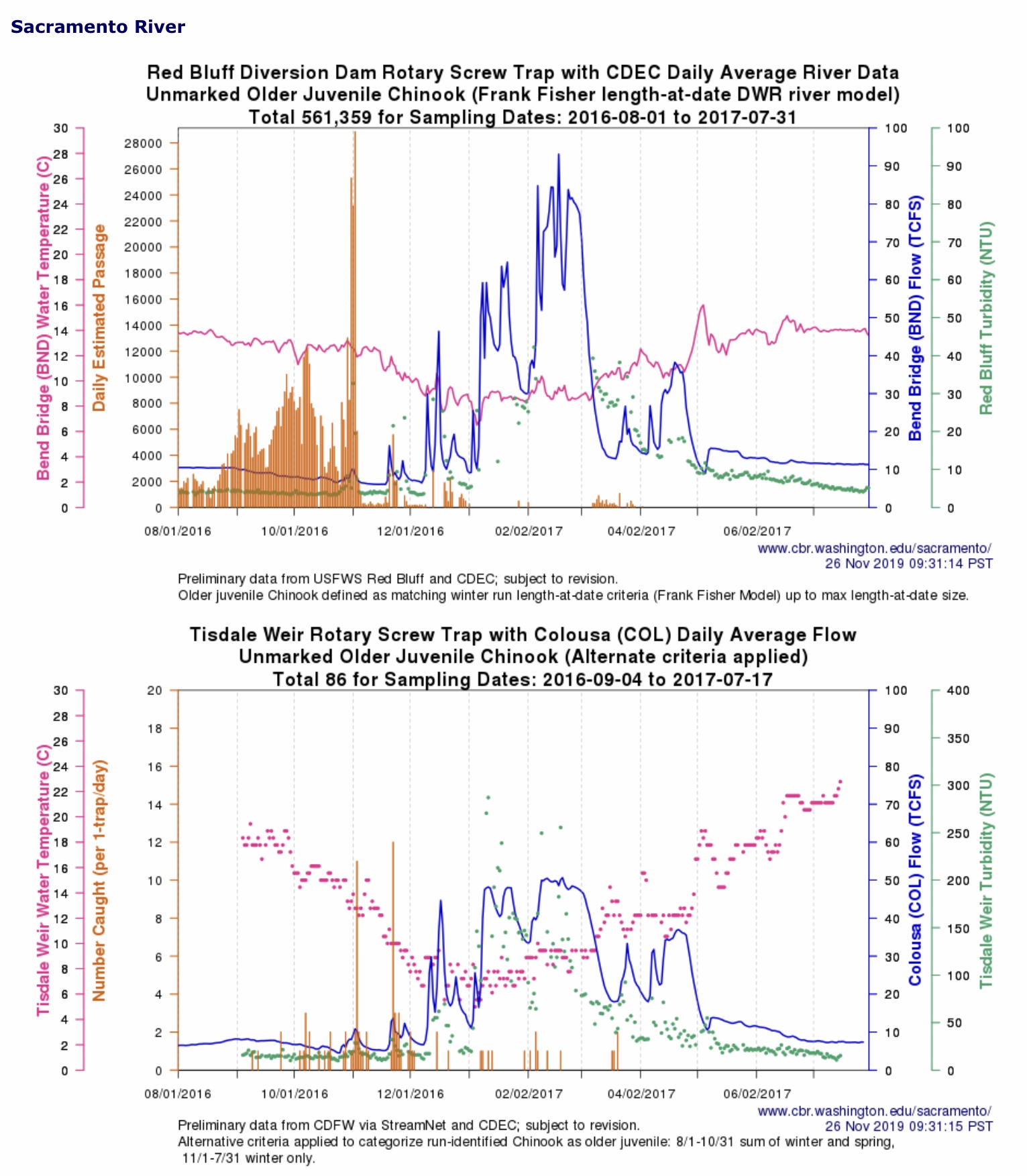

In my last posts on longfin smelt, I expressed some optimism about their recovery from the 2013-2015 drought based on 2017 and 2018 population data (Figure 1).1 I have changed my mind. In this wet water year 2019, the longfin have again crashed.

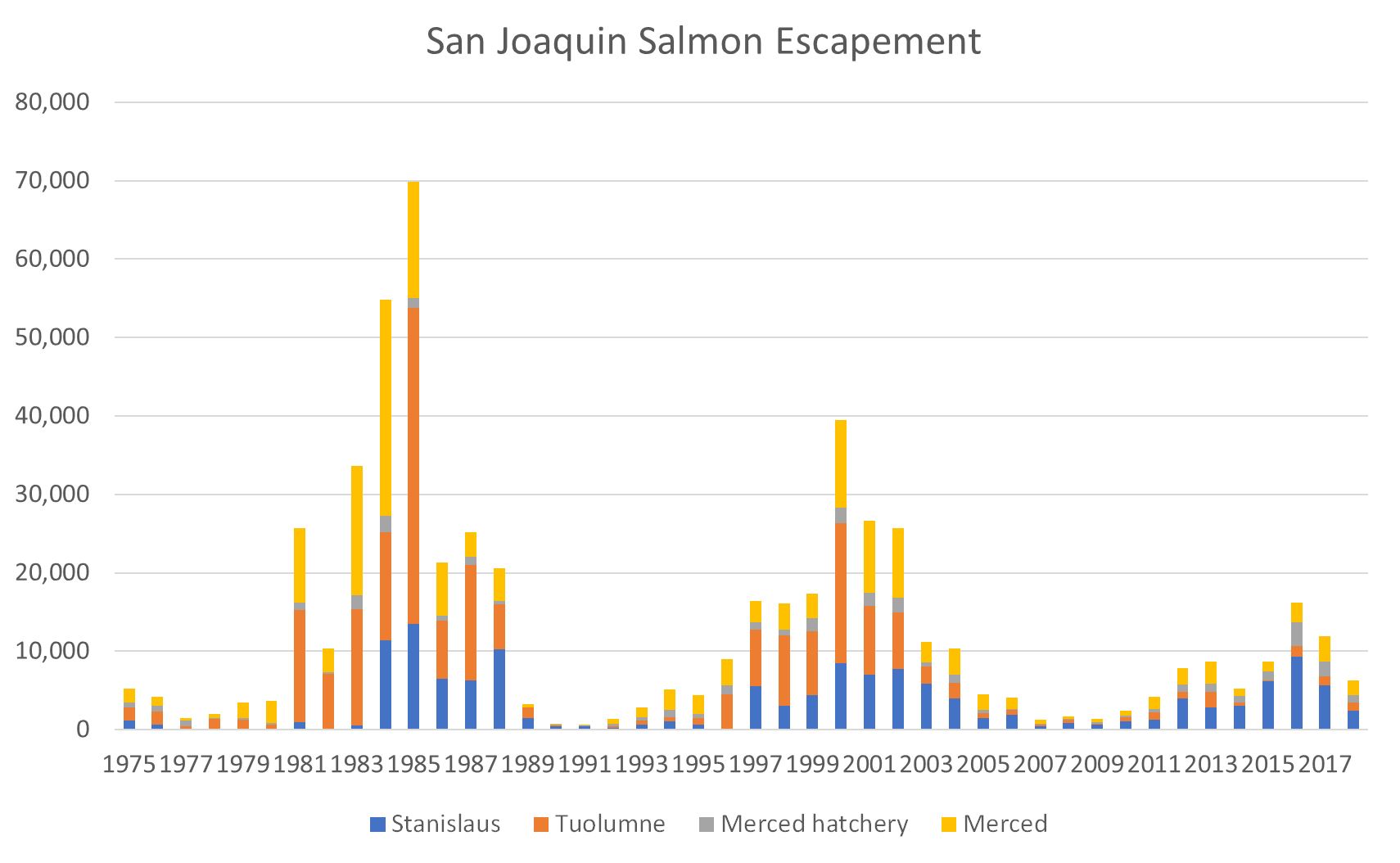

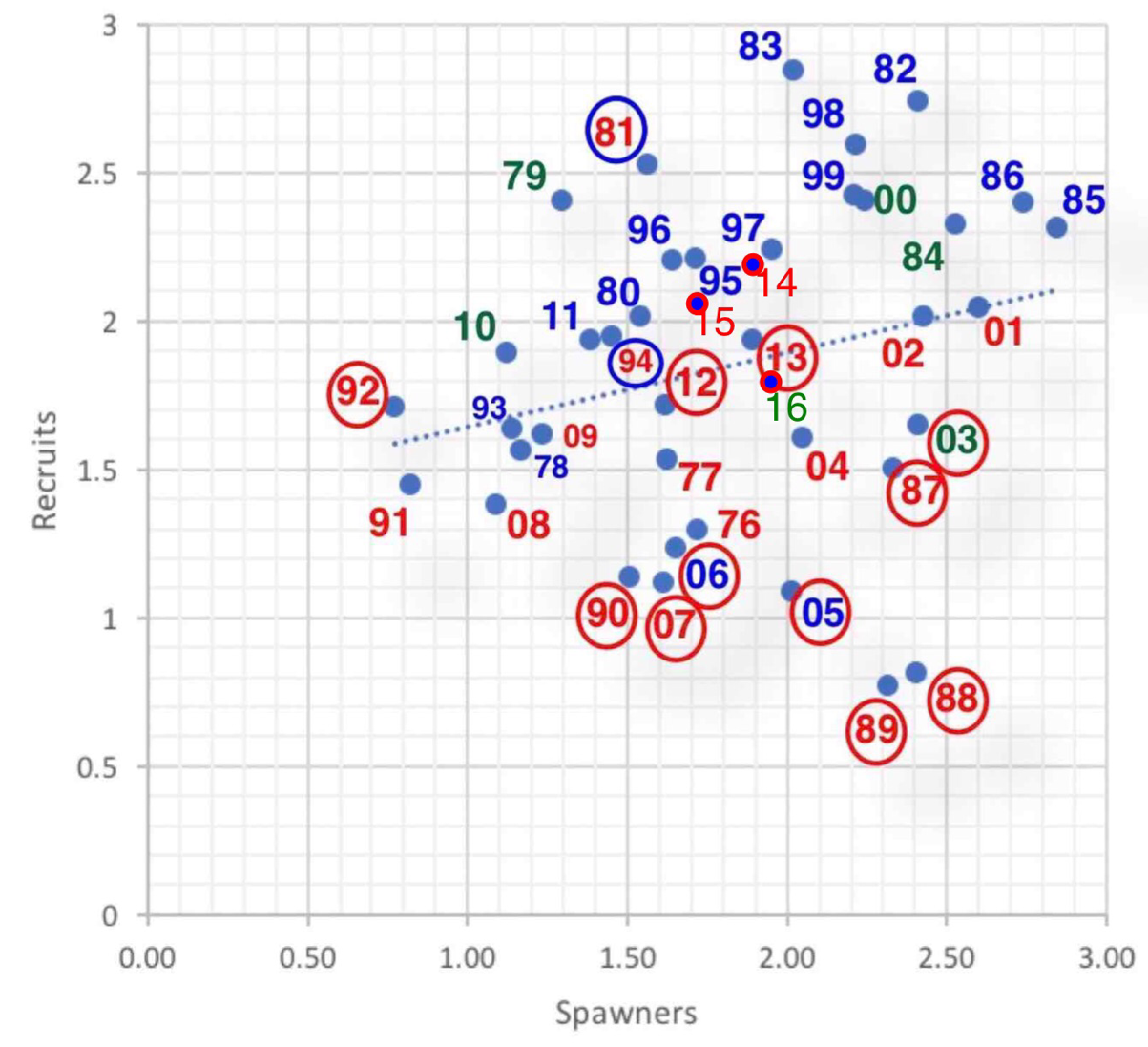

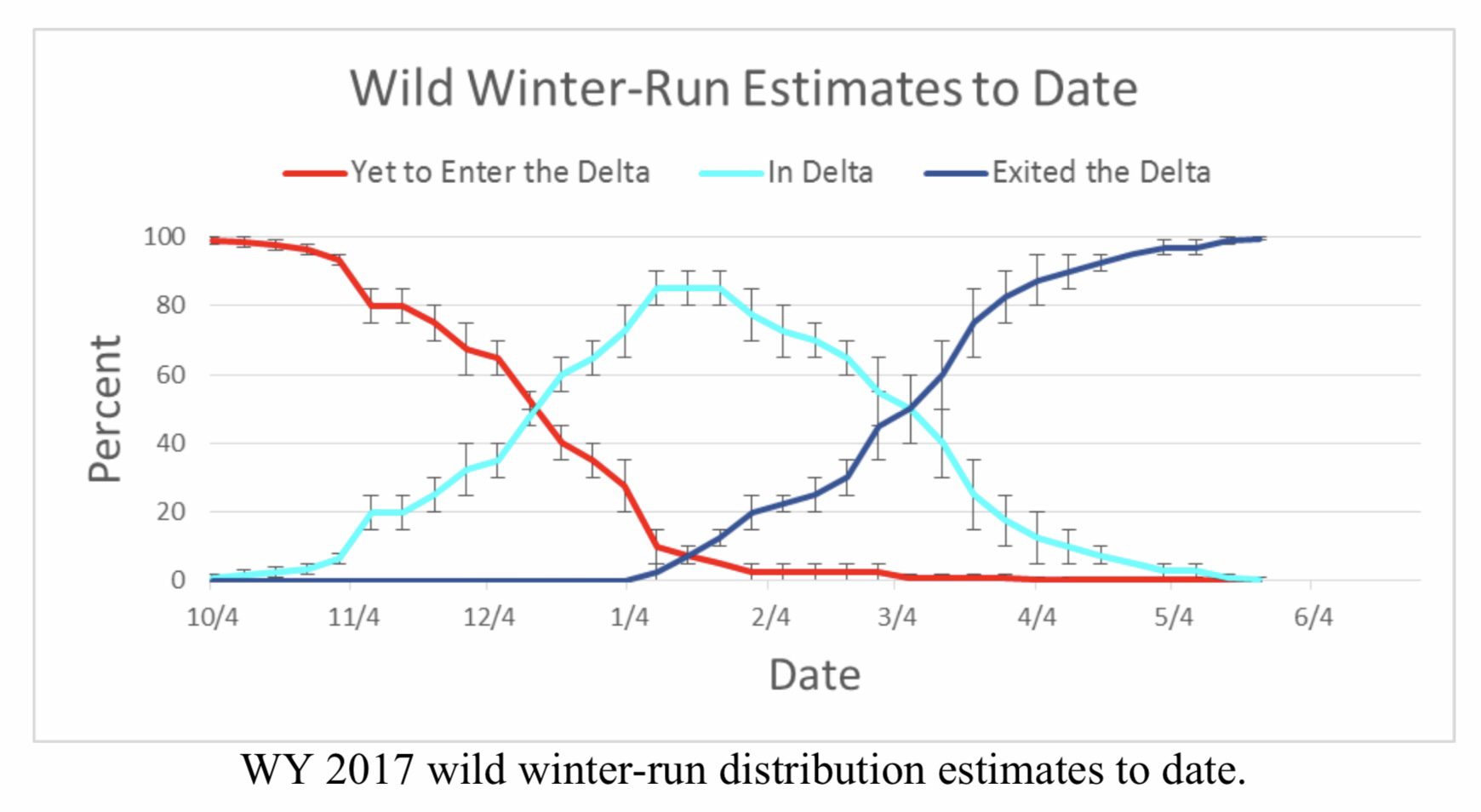

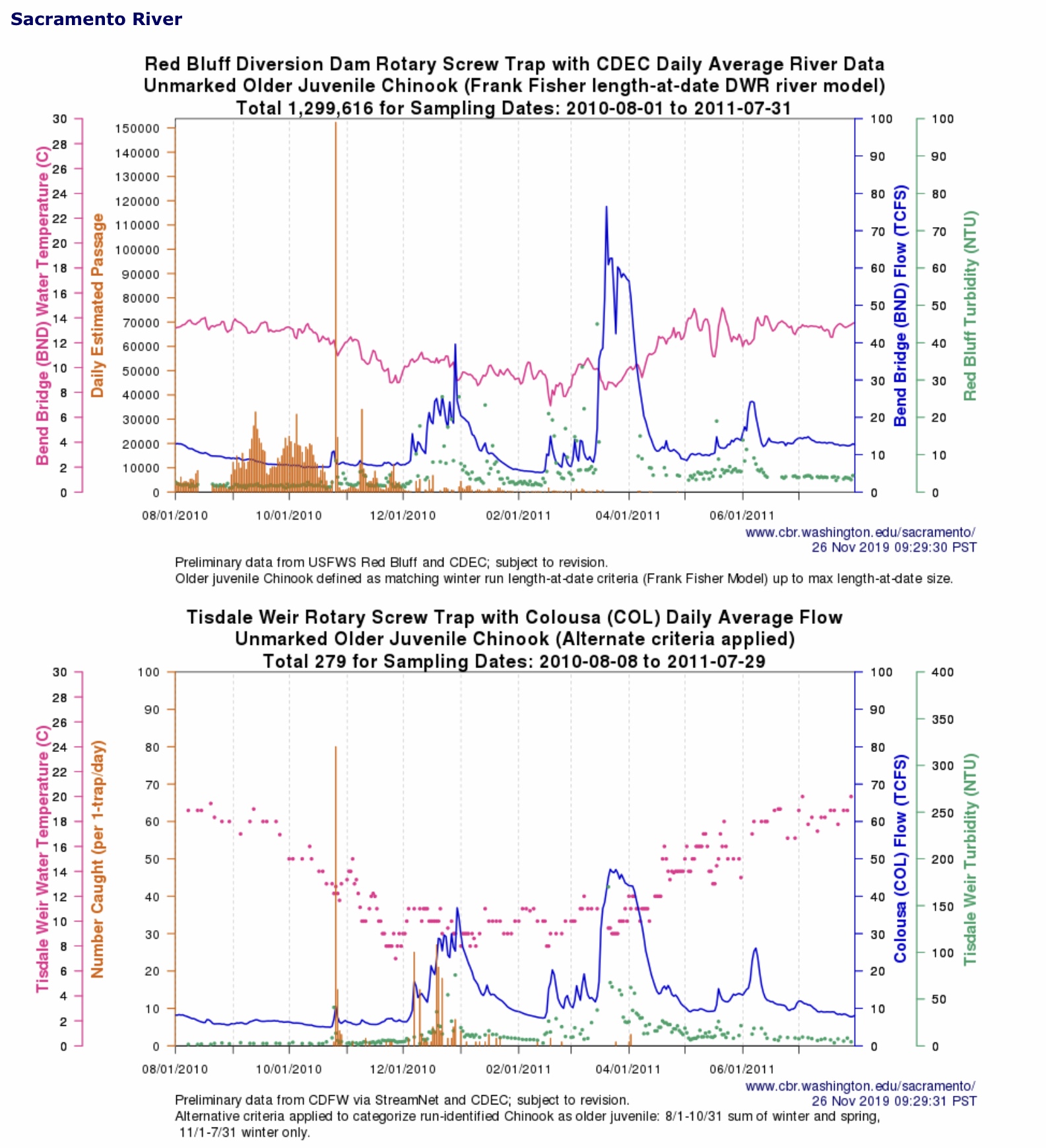

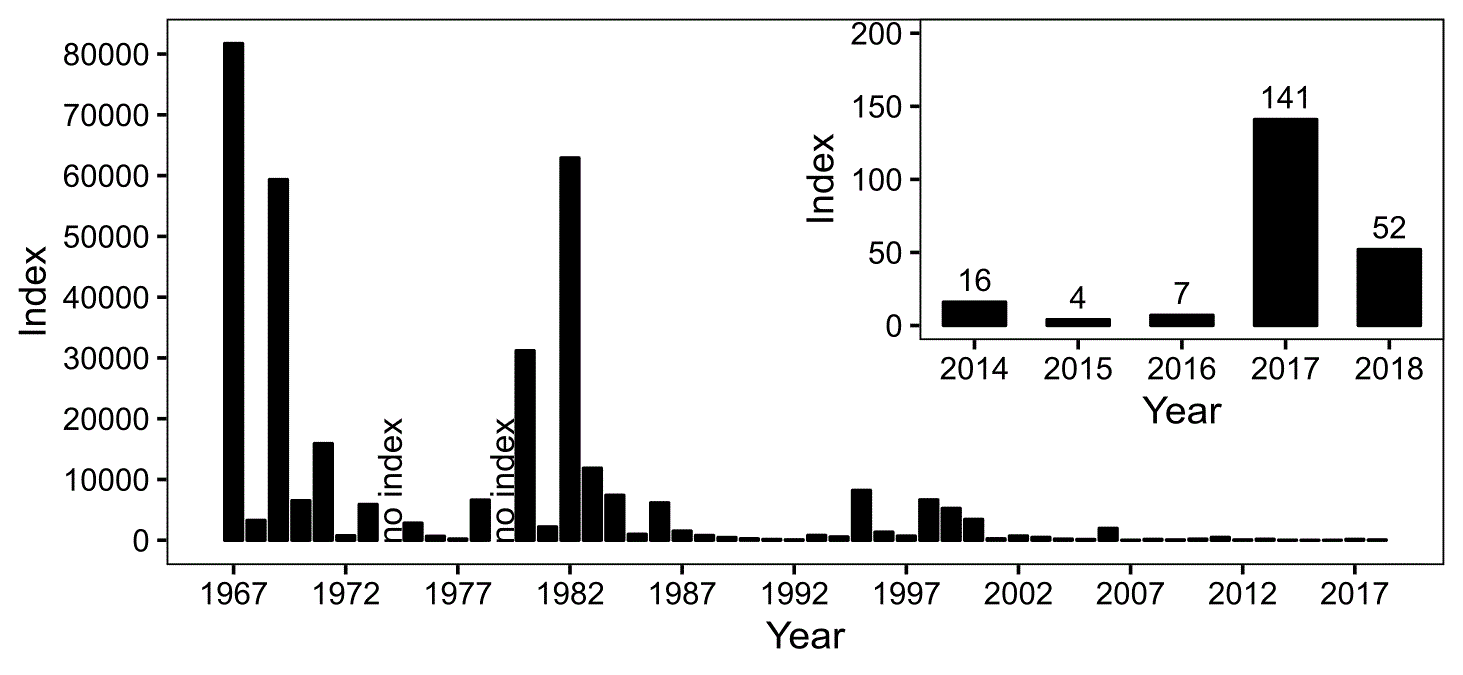

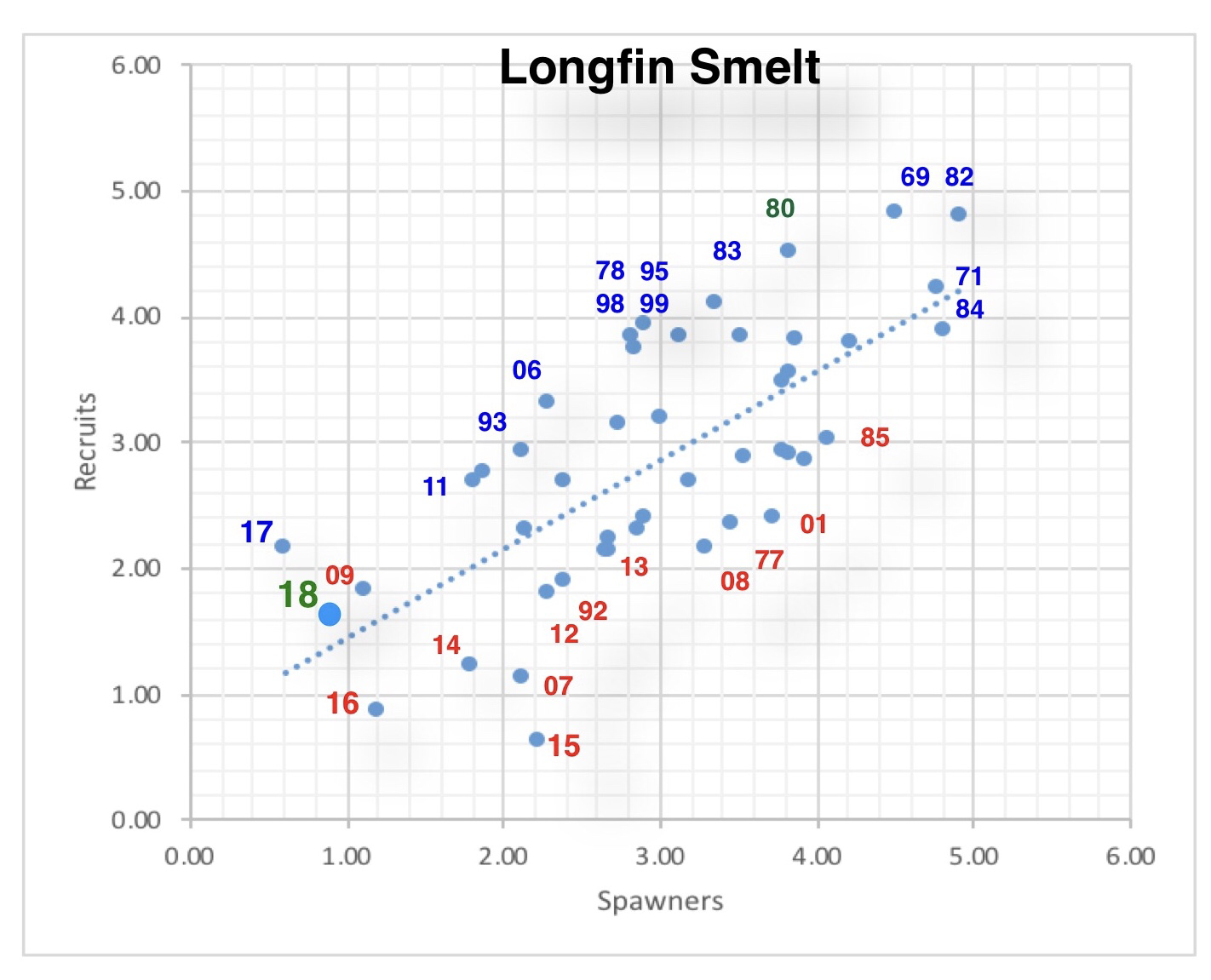

The long-term trend over four wet-year November adult trawl surveys, including this year (2019), continues downward (Figures 2-5). The trend portrays the underlying strong spawner-recruit relationship: the number of spawners (eggs) is the key factor that determines recruits. On top of that, poor recruitment in drier years (Figure 6) is driving recruitment-per-spawner down. There is 10-100 times higher recruitment from wetter years.

What is it about both dry years and wetter years like 2019 that is so bad? It is low Delta outflow and high exports in the November-December period.

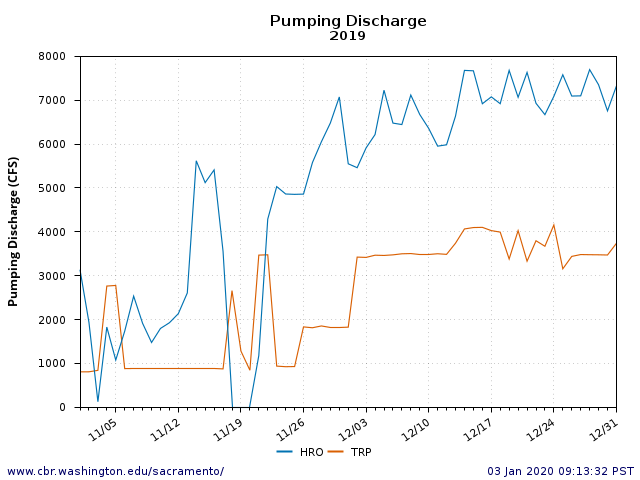

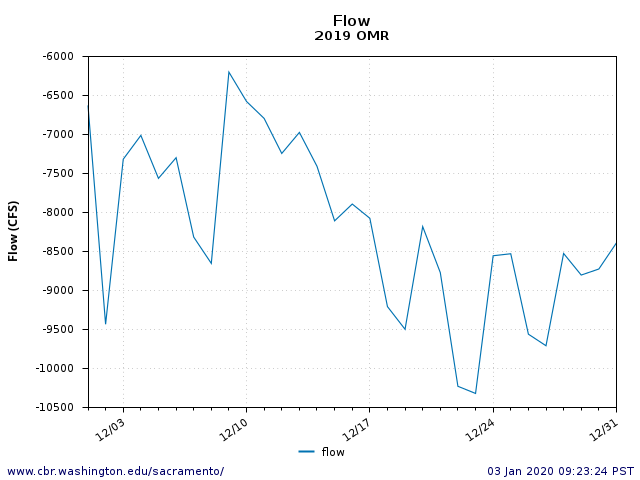

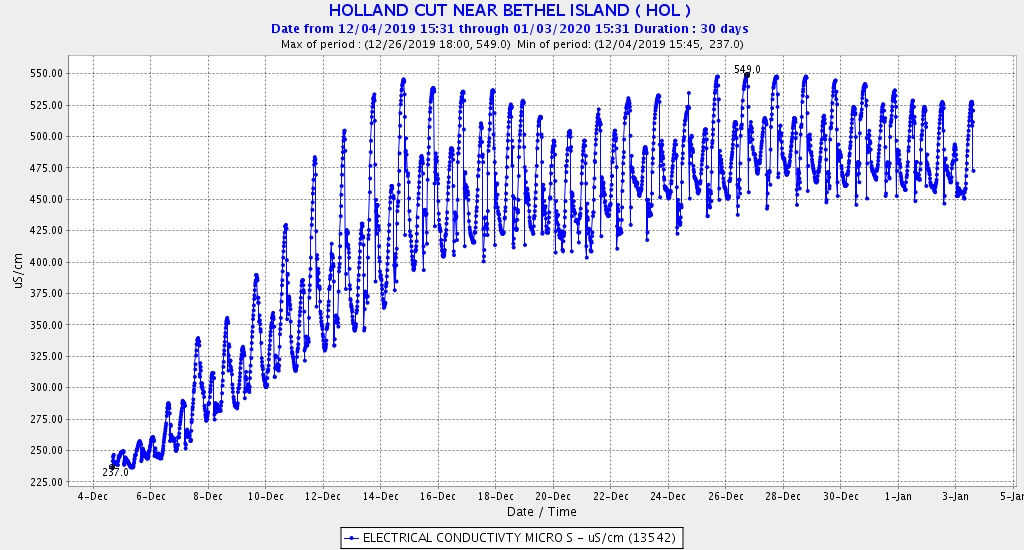

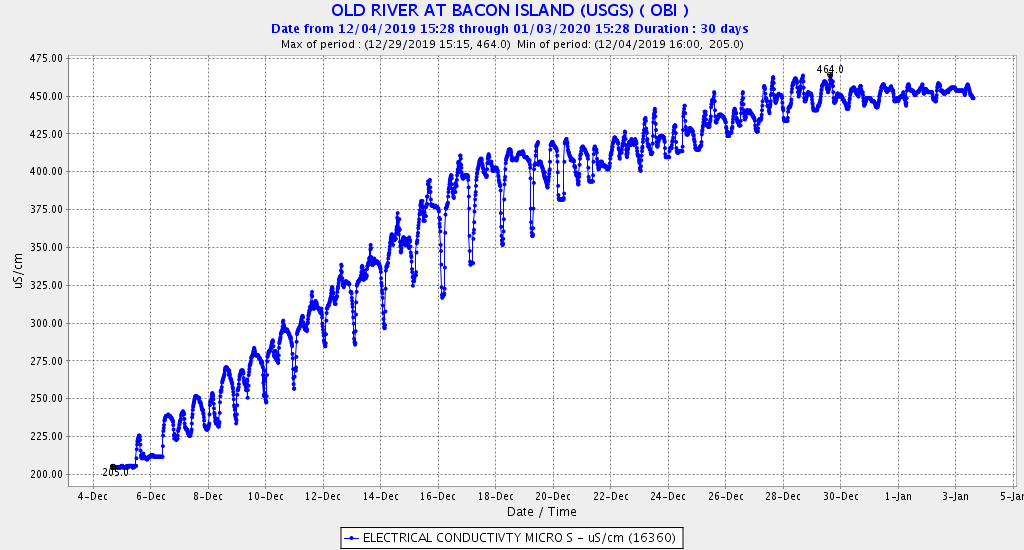

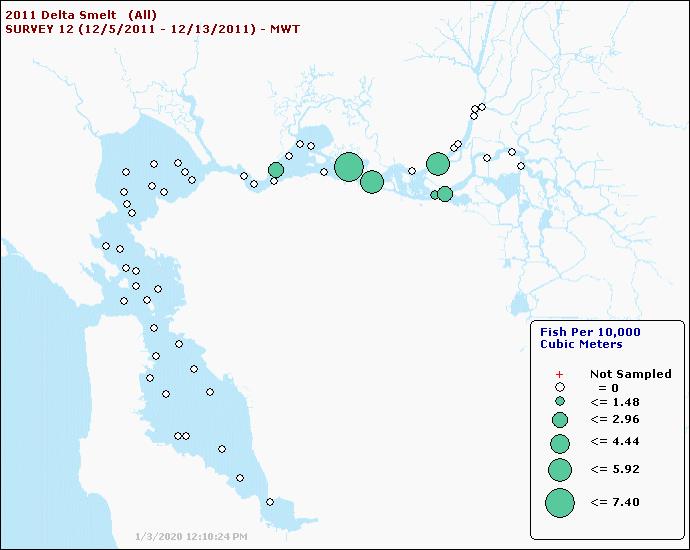

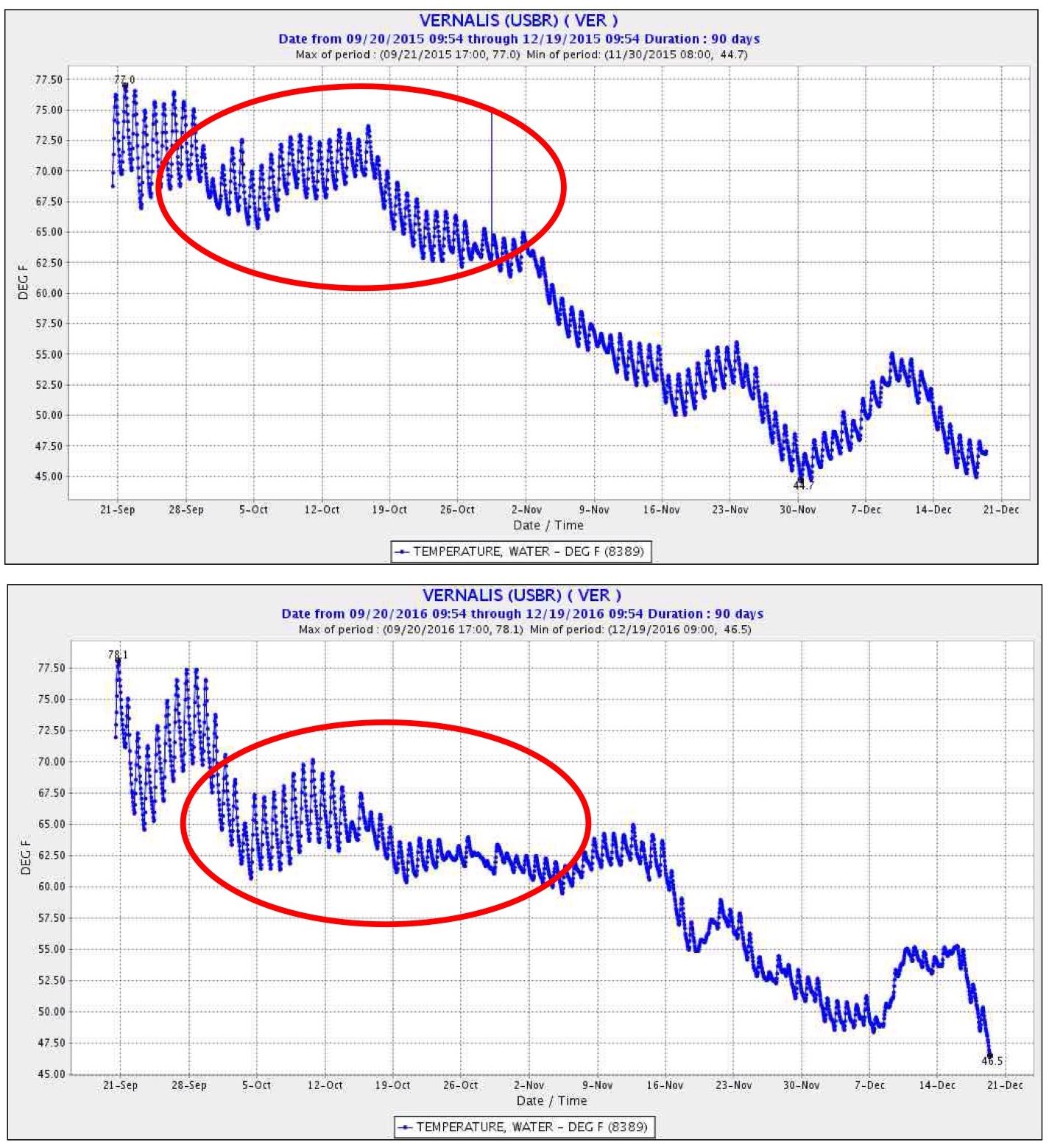

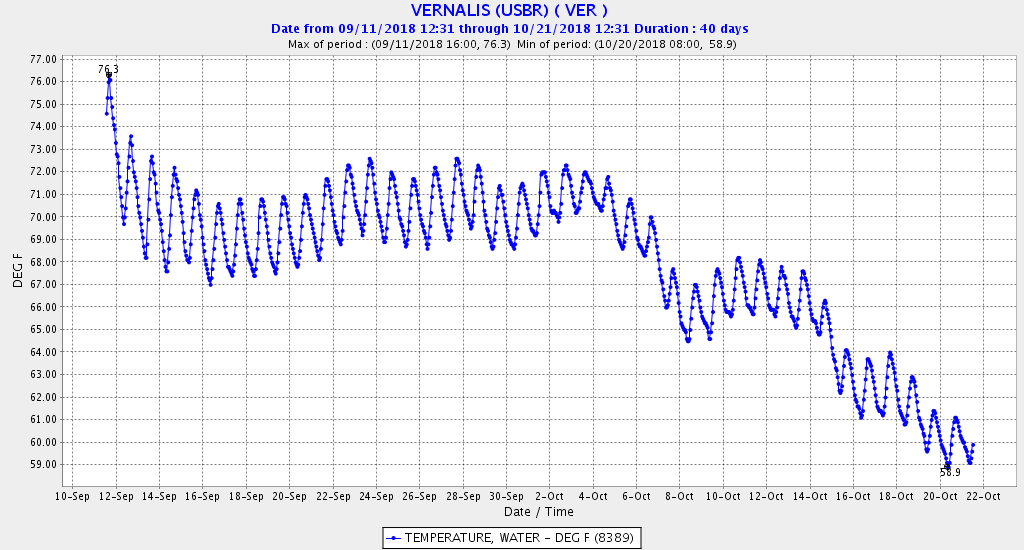

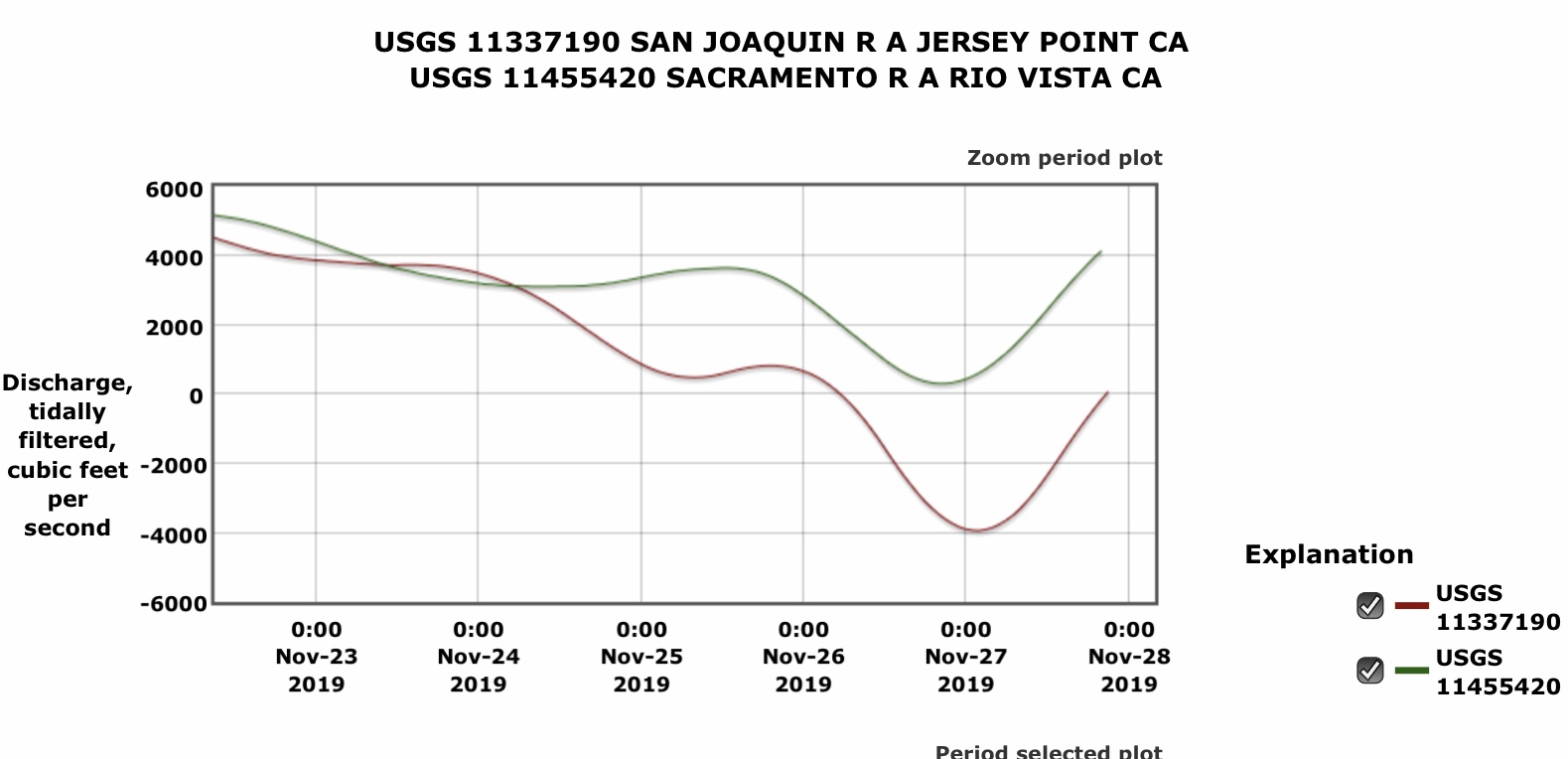

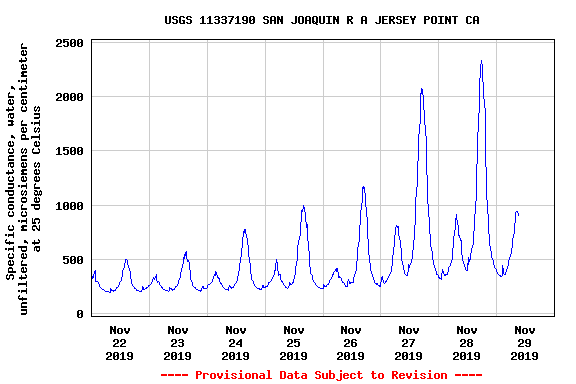

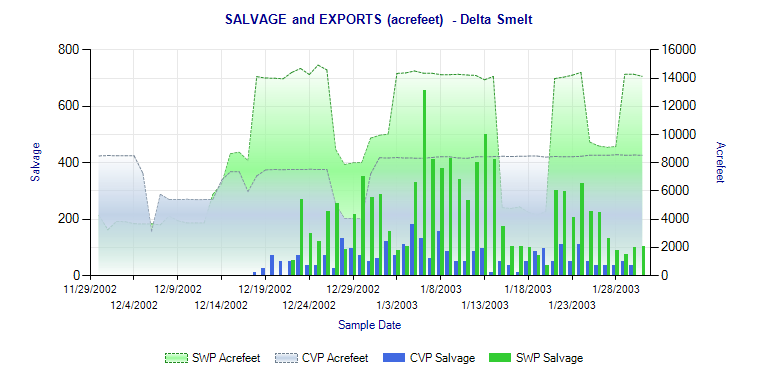

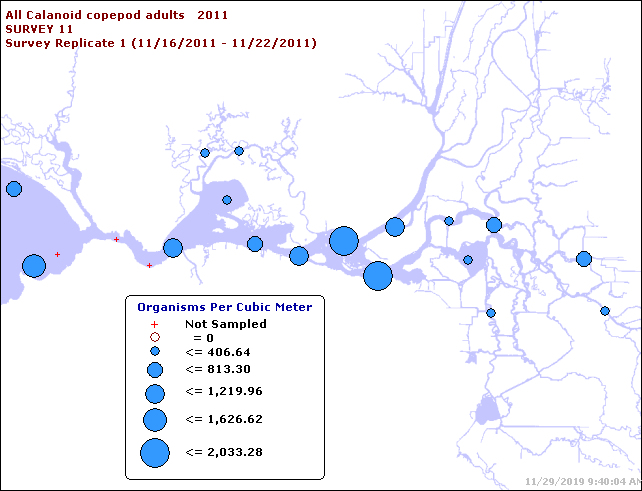

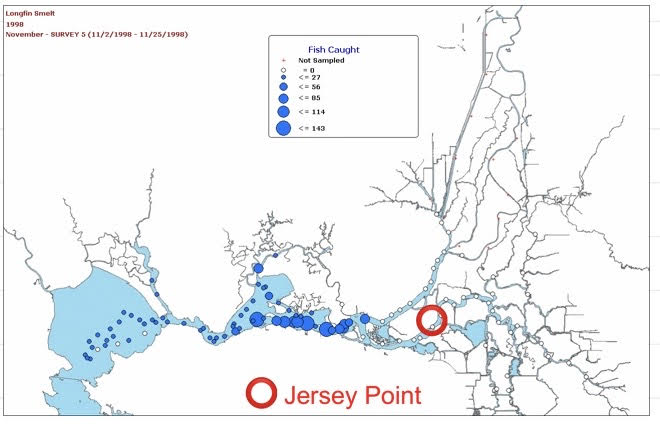

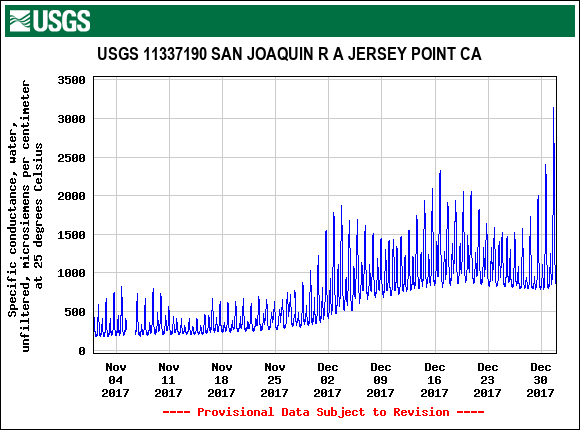

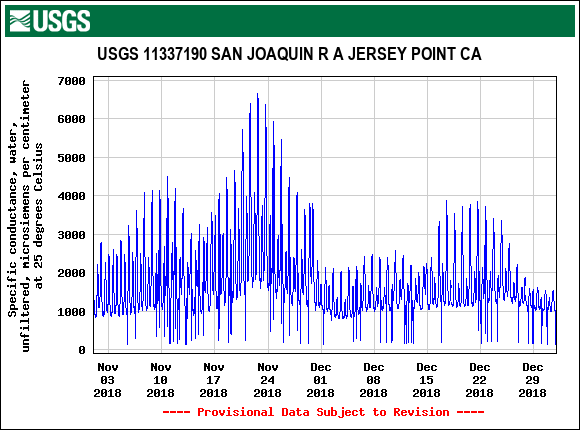

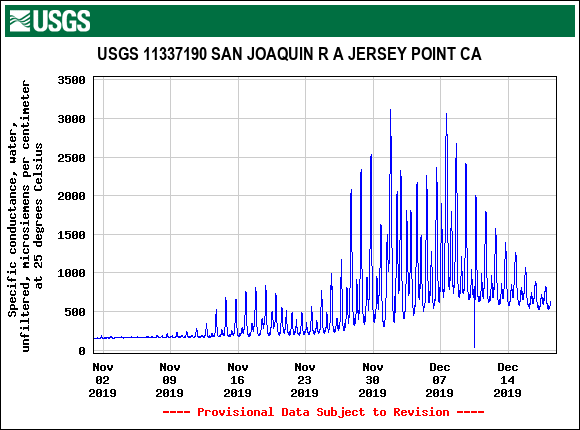

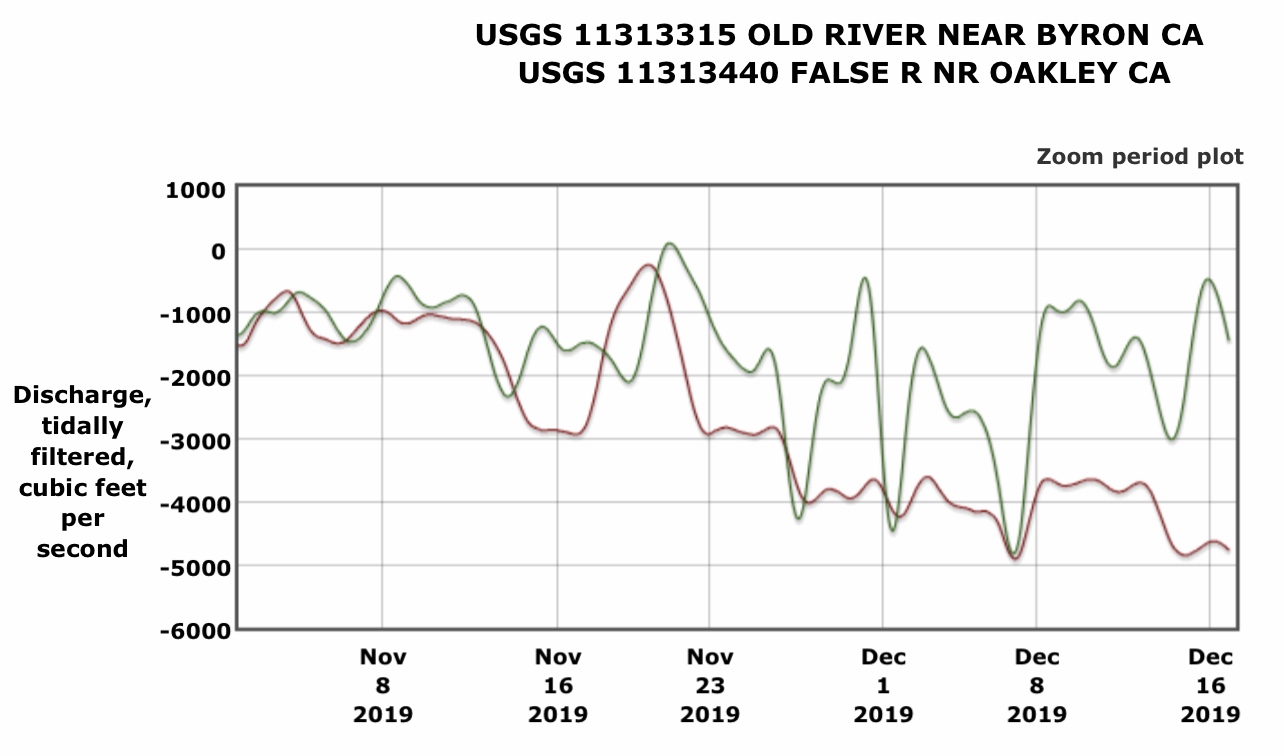

Longfin smelt spawn in November-December in fresh water.2 When their freshwater habitat is in the San Joaquin channel in the central Delta upstream of Jersey Point (See location in Figure 2, Figures 7 and 8), the newly hatched larvae are highly susceptible to unlimited November and December exports. Although 2019 was a wet year, these conditions were present in November and December (Figures 9 and 10).

The prognosis for longfin smelt under current and planned water operations in the Delta is grim. The state and federal water projects need to increase Delta outflow and reduce exports in November and December to reduce spawning of longfin smelt in the central and south Delta.

Figure 1. Fall Midwater Trawl Index for longfin smelt, 1967-2018. Source: http://www.dfg.ca.gov/delta/data/fmwt/indices.asp

Figure 2. Catch distribution of longfin smelt adults in the November 1998 fall midwater trawl survey.

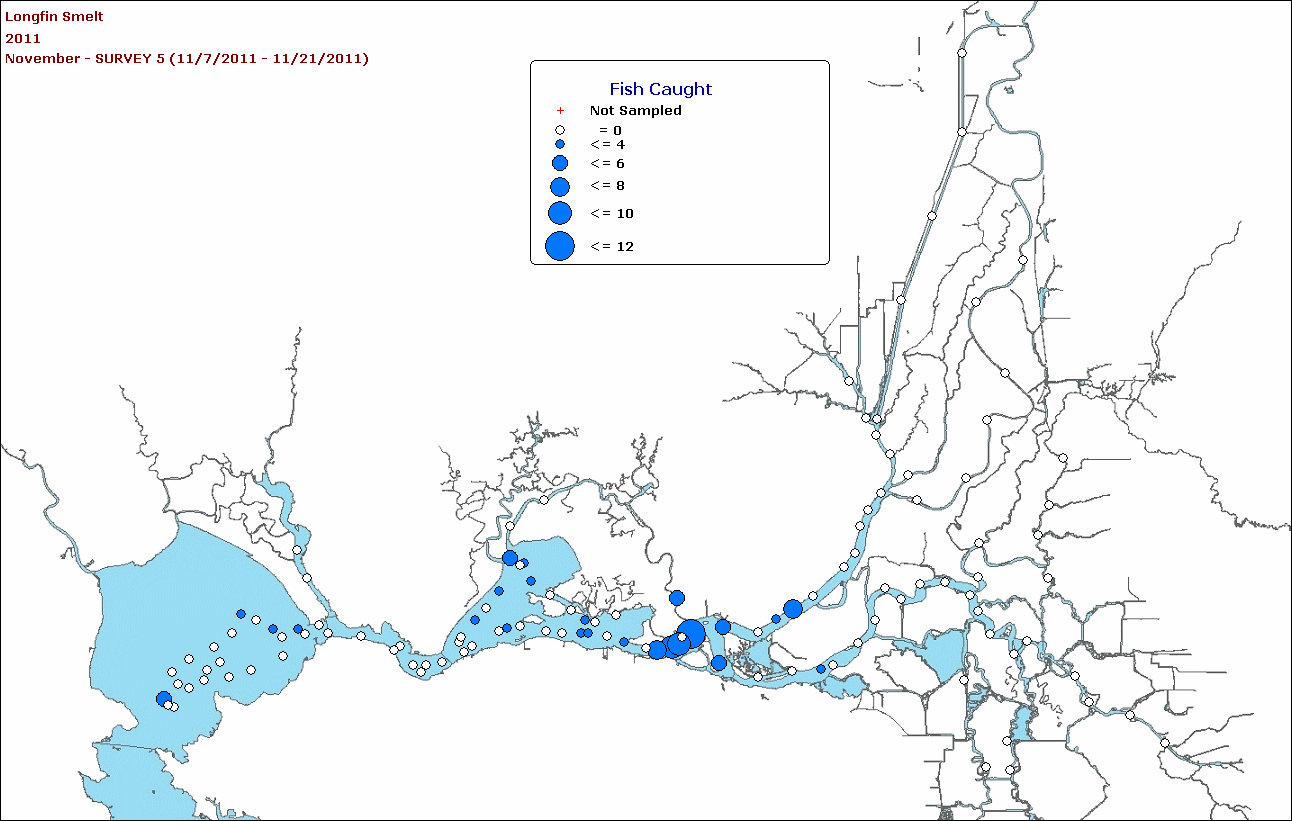

Figure 3. Catch distribution of longfin smelt adults in the November 2011 fall midwater trawl survey.

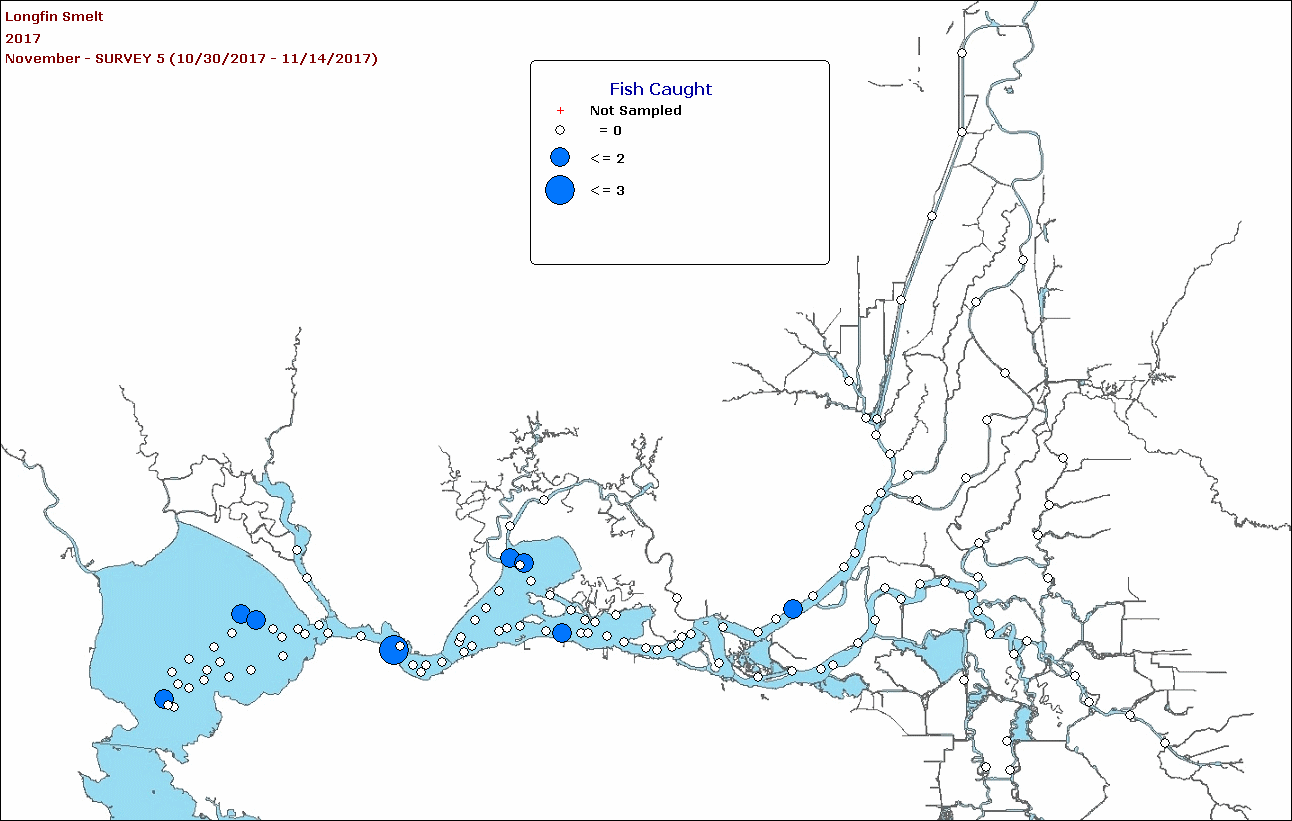

Figure 4. Catch distribution of longfin smelt adults in the November 2017 fall midwater trawl survey.

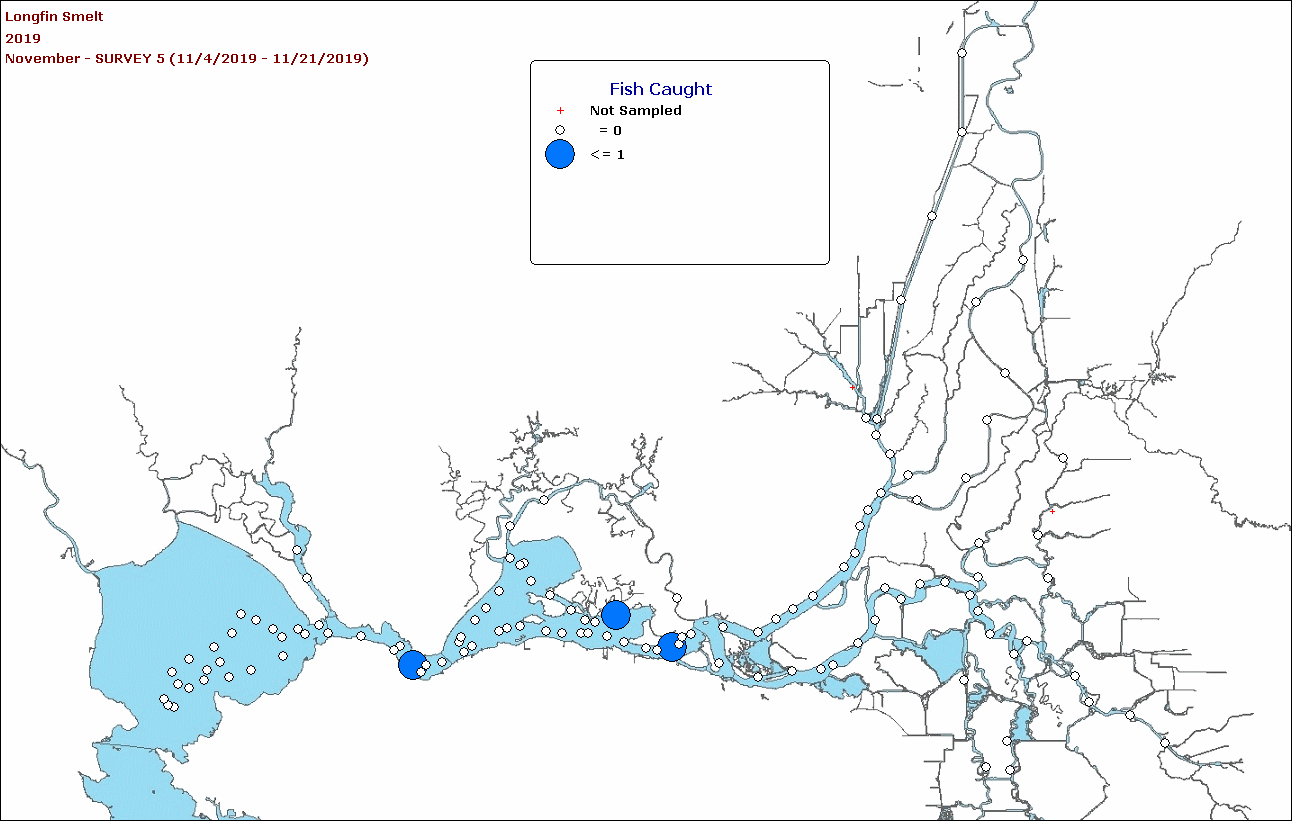

Figure 5. Catch distribution of longfin smelt adults in the November 2019 fall midwater trawl survey.

Figure 6. Longfin Recruits (Fall Midwater Trawl Index) vs Spawners (Index from two years prior) in Log10 scale. The relationship is very strong and highly statistically significant. Adding Delta outflow in winter-spring as a factor makes the relationship even stronger. Recruits per spawner are dramatically lower in drier, lower-outflow years (red years). Spawners in 2017 and 2018 were at record low levels. Recruits in 2011 and 2017 were relatively high because the Fall X2 provision in the 2008 Biological Opinion was implemented. Source: http://calsport.org/fisheriesblog/?p=2513.

Figure 7. Salinity (EC) in November and December 2017 at Jersey Point in the lower San Joaquin River channel of the west Delta. Spawning would occur in fresh water (below 500 EC).

Figure 8. Salinity (EC) in November and December 2018 at Jersey Point in the lower San Joaquin River channel of the west Delta. Spawning would occur in freshwater (below 500 EC), which occurred upstream of Jersey Point.

Figure 9. Salinity (EC) in November and December 2019 at Jersey Point in the lower San Joaquin River channel of the west Delta. Spawning would occur in freshwater (below 500 EC), which occurred upstream of Jersey Point.

Figure 10. Tidally filtered flow in two channels in the lower San Joaquin River upstream of Jersey Point, portraying net flows toward to the south Delta export pumps.