NEWS HEADLINES – All basically true.

- California’s reservoirs face dangerously low levels

- California faces worst drought in decades: ‘Economic disaster’

- Restore the Delta, others file protest over Temporary Urgency Change Petitions for the SWP and CVP

- 74% of California and 52% of the Western U.S. now in ‘exceptional’ drought

- A ‘megadrought’ in California is expected to lead to water shortages for production of everything from avocados to almonds, and could cause prices to rise.

- THE 2021 WESTERN DROUGHT: WHAT TO EXPECT AS CONDITIONS WORSEN

- The Drought In The Western U.S. Is Getting Bad. Climate Change Is Making It Worse

- TRULY AN EMERGENCY’: HOW DROUGHT RETURNED TO CALIFORNIA – AND WHAT LIES AHEAD

- Endangered-Sacramento-River-winter-Chinook-salmon-are-dying-before-spawning-below-Keswick-Dam

- Will California Save the Last Winter Run Salmon This Year?

- Conservationists say time running out to save endangered salmon in Sacramento River

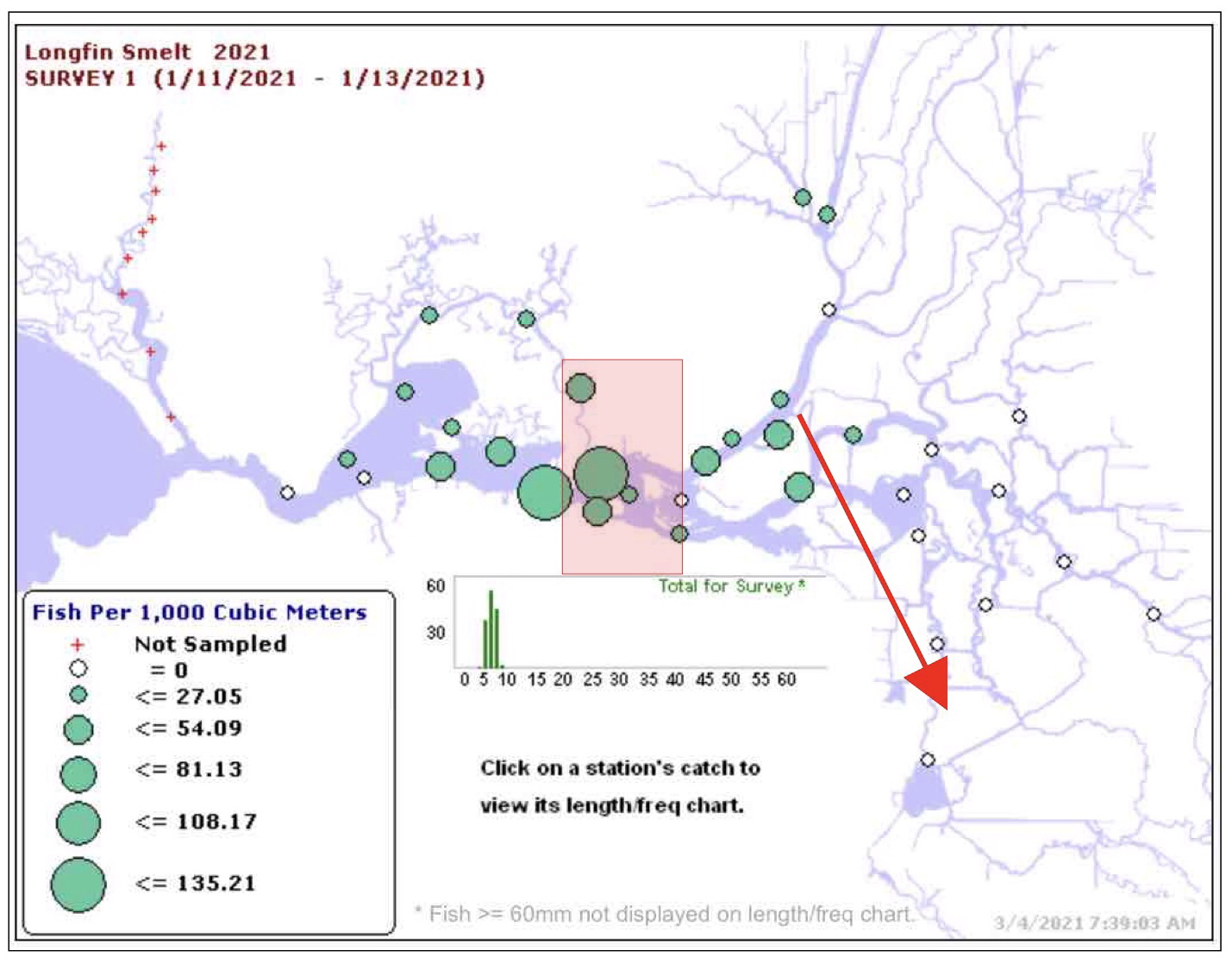

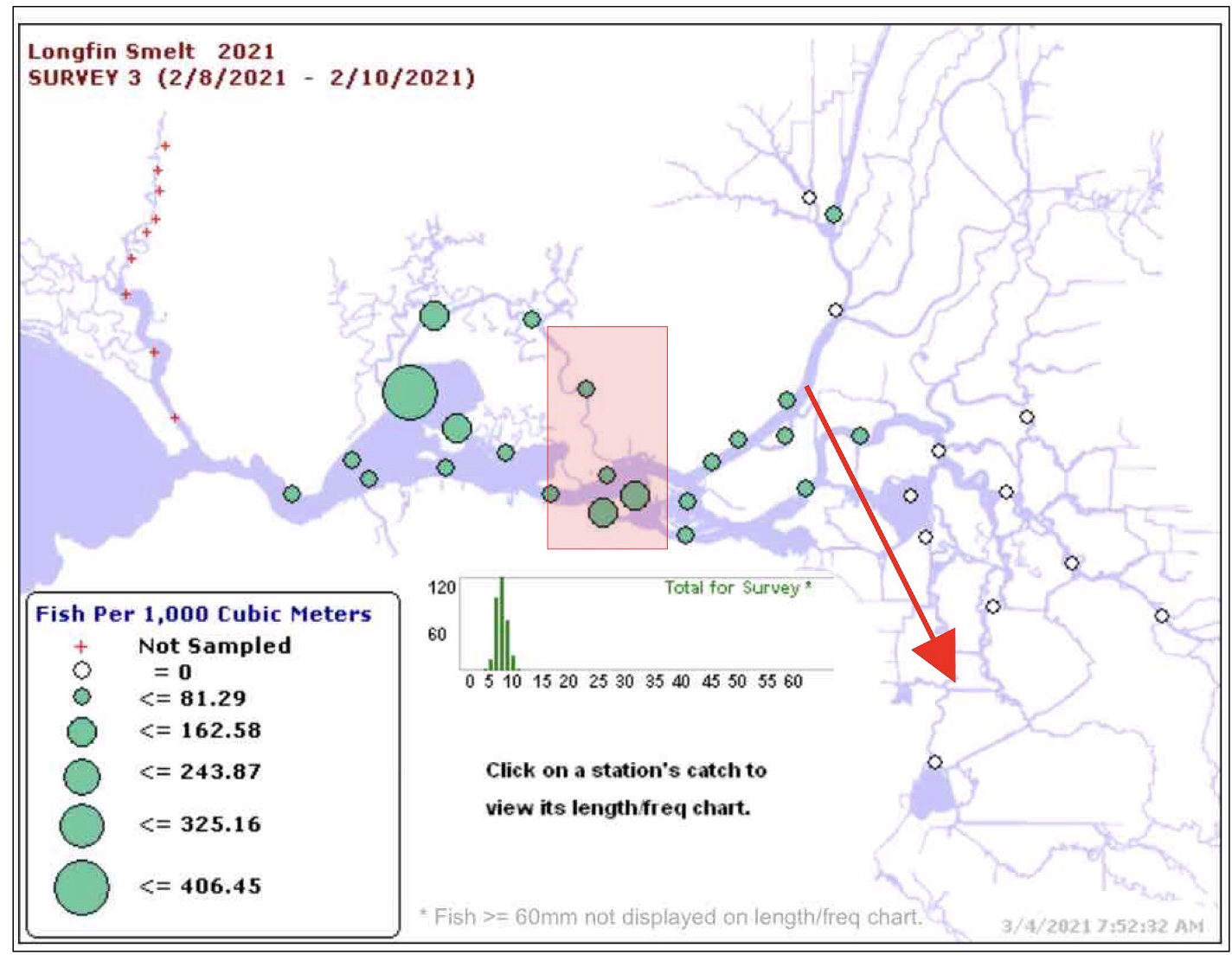

Where we stand now

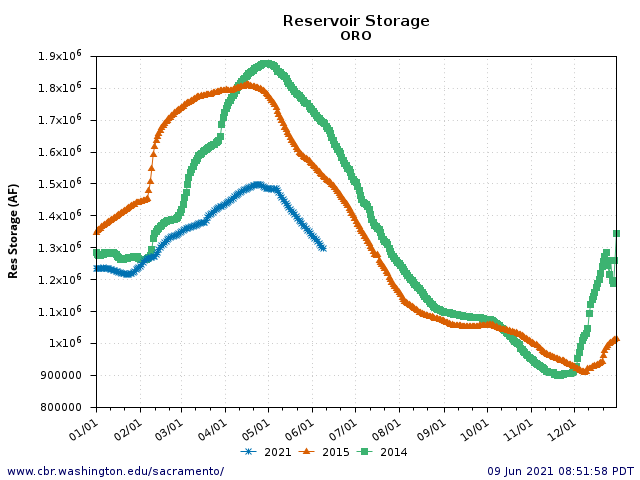

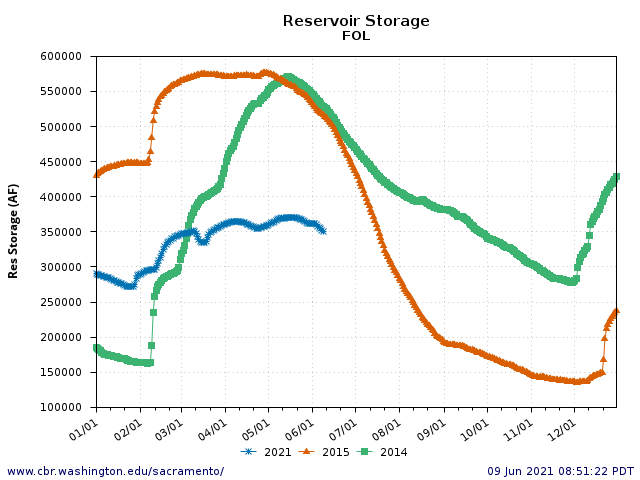

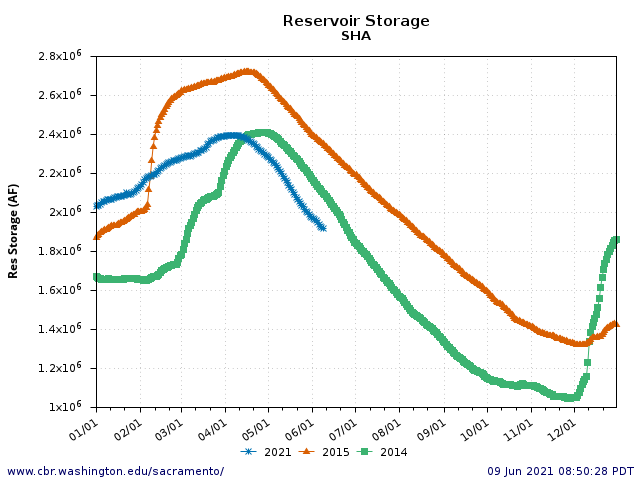

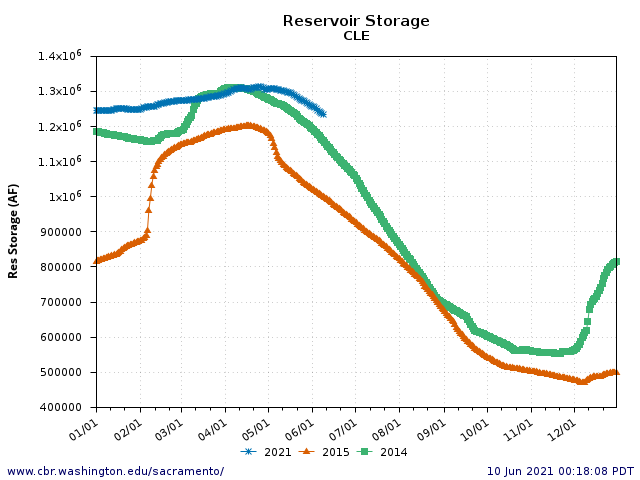

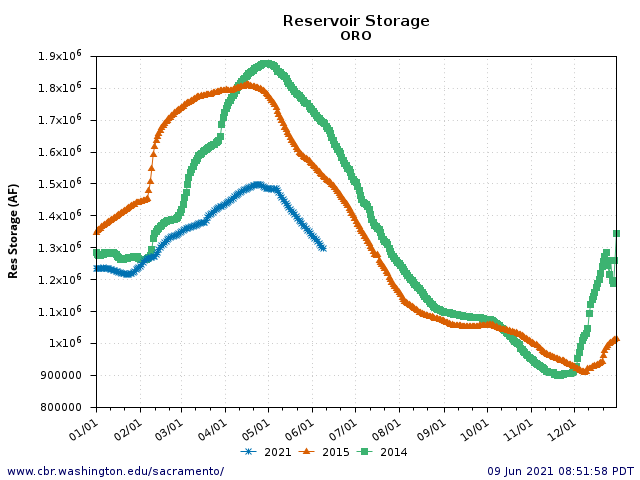

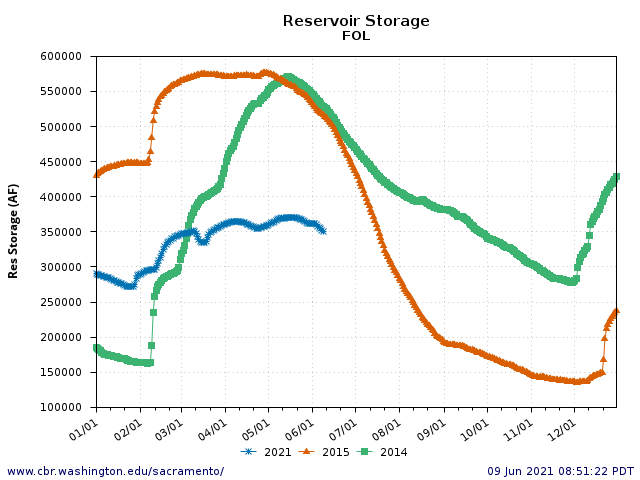

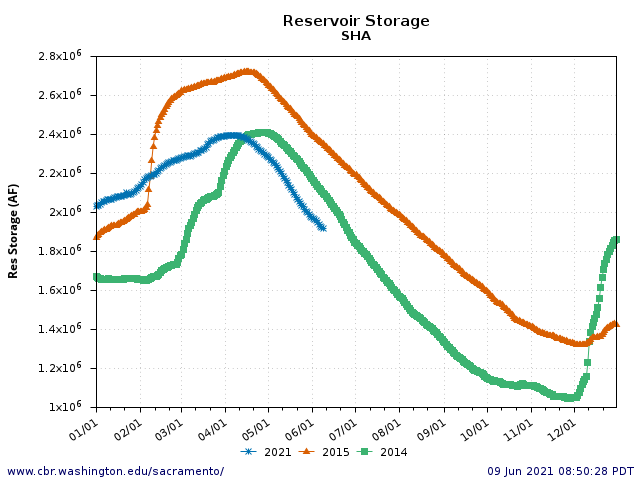

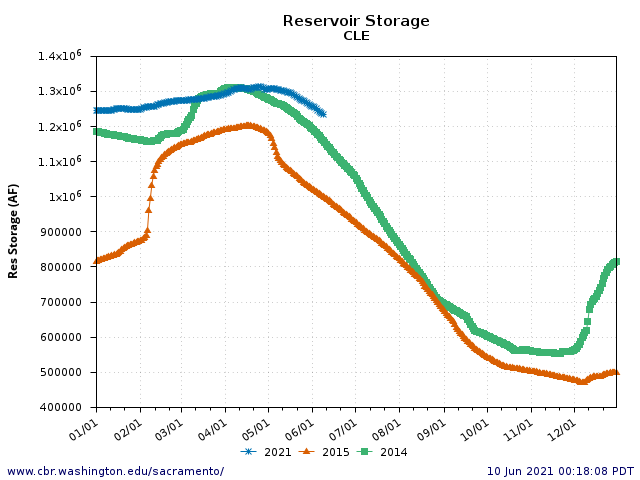

Water Storage – Water levels of the major reservoirs of the Sacramento Valley are low and getting lower, even lower than critical drought years 2014 and 2015 (Figures 1-3). Trinity Lake is slightly higher than 2014 and 2015 (Figure 4).

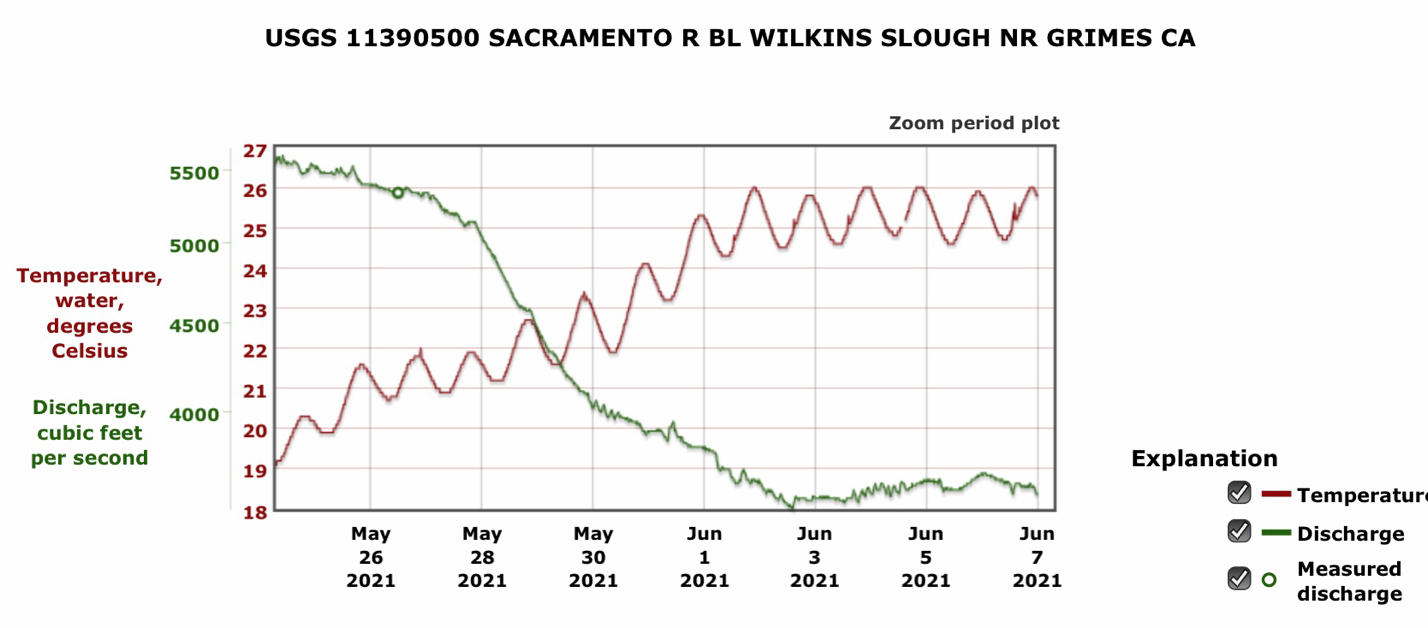

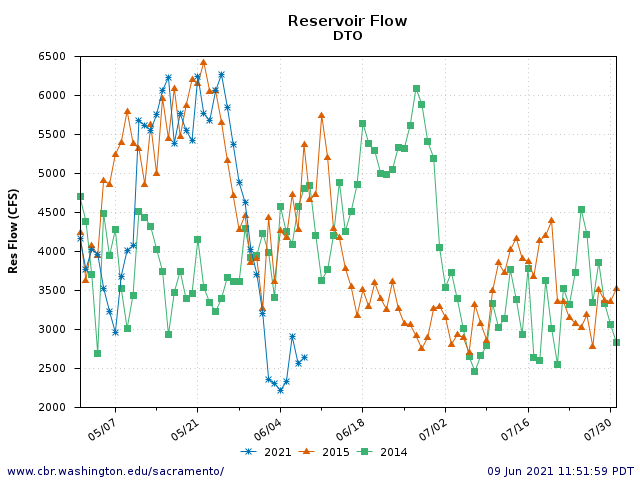

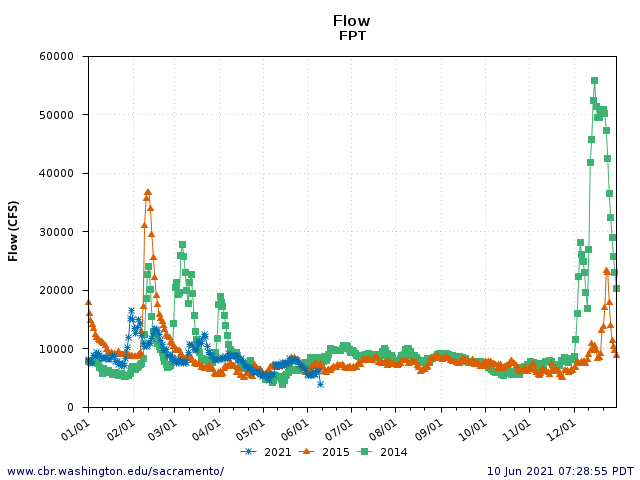

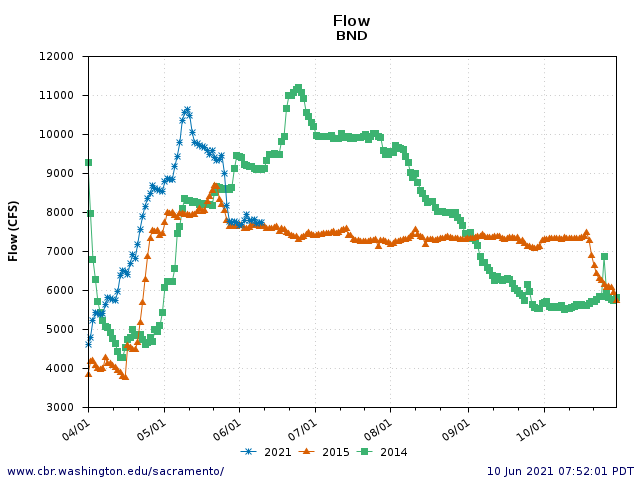

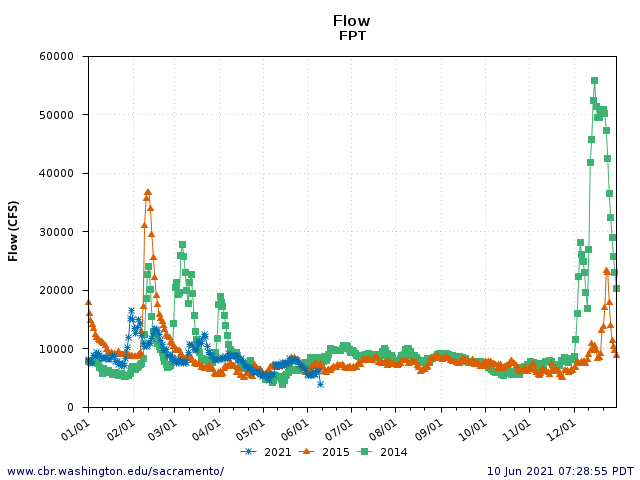

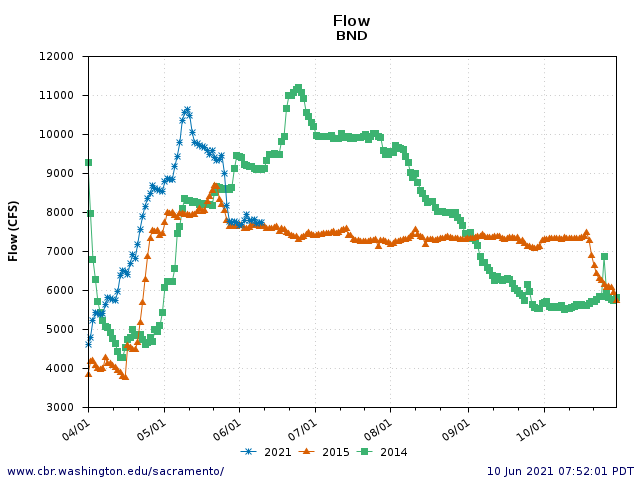

River Flows – Runoff from the Valley where the Sacramento River enters the Delta at Freeport has been lower than in 2014 or 2015 (Figure 5). Sacramento River flow where it enters the Valley below Shasta Reservoir at Bend Bridge near Red Bluff was higher in April-May 2021 than 2014 or 2015 (Figure 6), reflecting higher 2021 demand for Shasta storage.

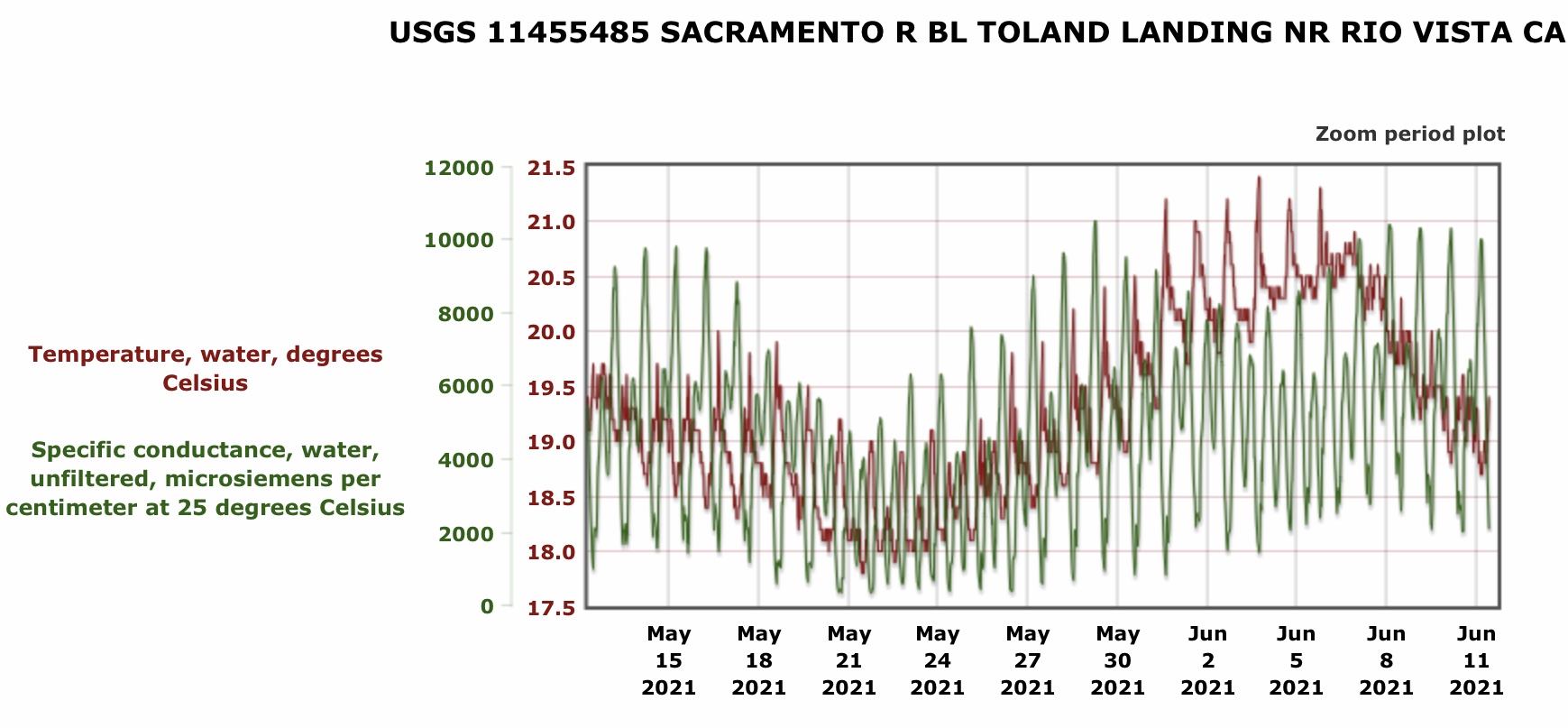

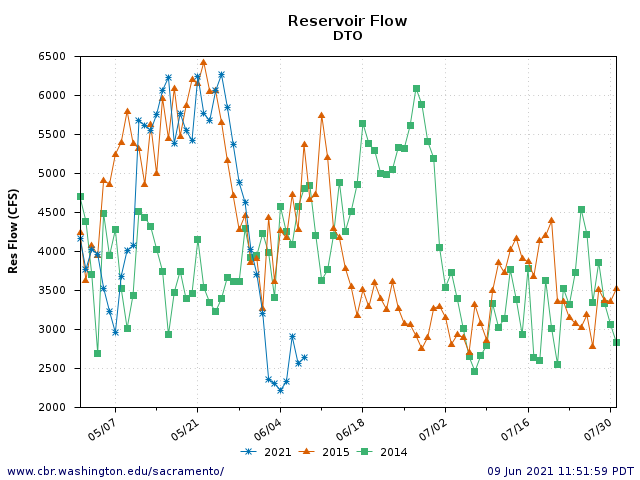

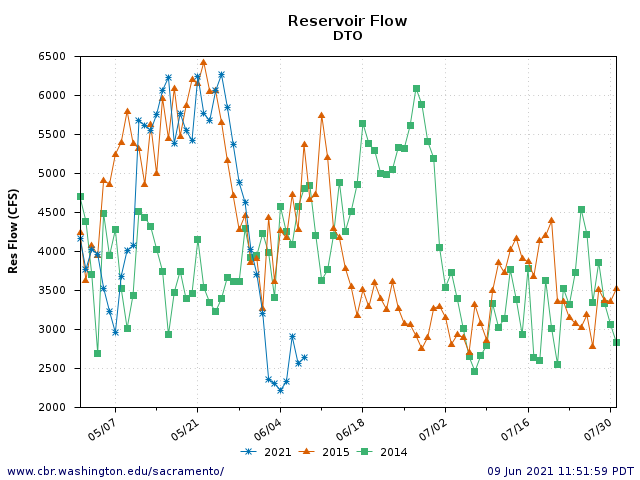

Delta Outflow – Delta outflow was at minimum levels of 4000-6000 cfs daily average in April-May 2021 to meet water quality standards for critical water years as in 2014 and 2015 (Figure 7). That changed in early June, when the State Water Board approved a Temporary Urgent Change Petition, and Delta Outflow dropped to a roughly calculated 2000-3000 cfs. Note total reservoir releases to Central Valley rivers at the beginning of June 2021 was approximately 18,000 cfs, and total water supply diversions was conservatively 15,000 cfs (83%). Of these diversions, there were about 5000 cfs diverted from the Sacramento River and its tributaries, 5000 cfs from the San Joaquin River and its tributaries, 3000 cfs diverted within the Delta, and 2000 cfs diverted through the Delta export pumps.

Shasta Choices and Tradeoffs

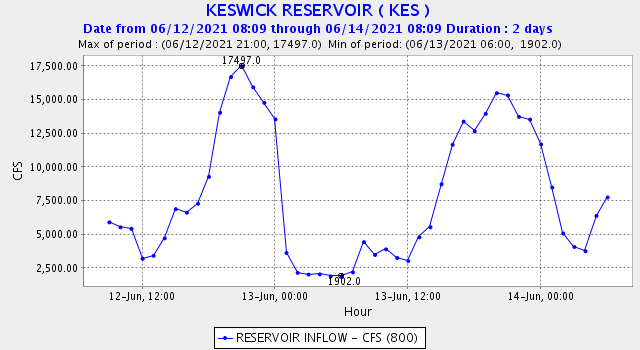

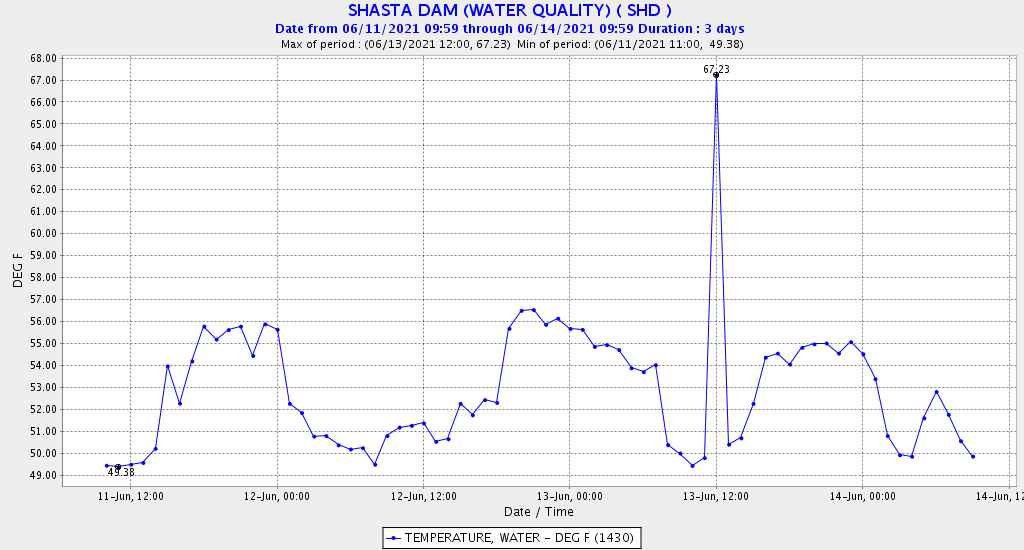

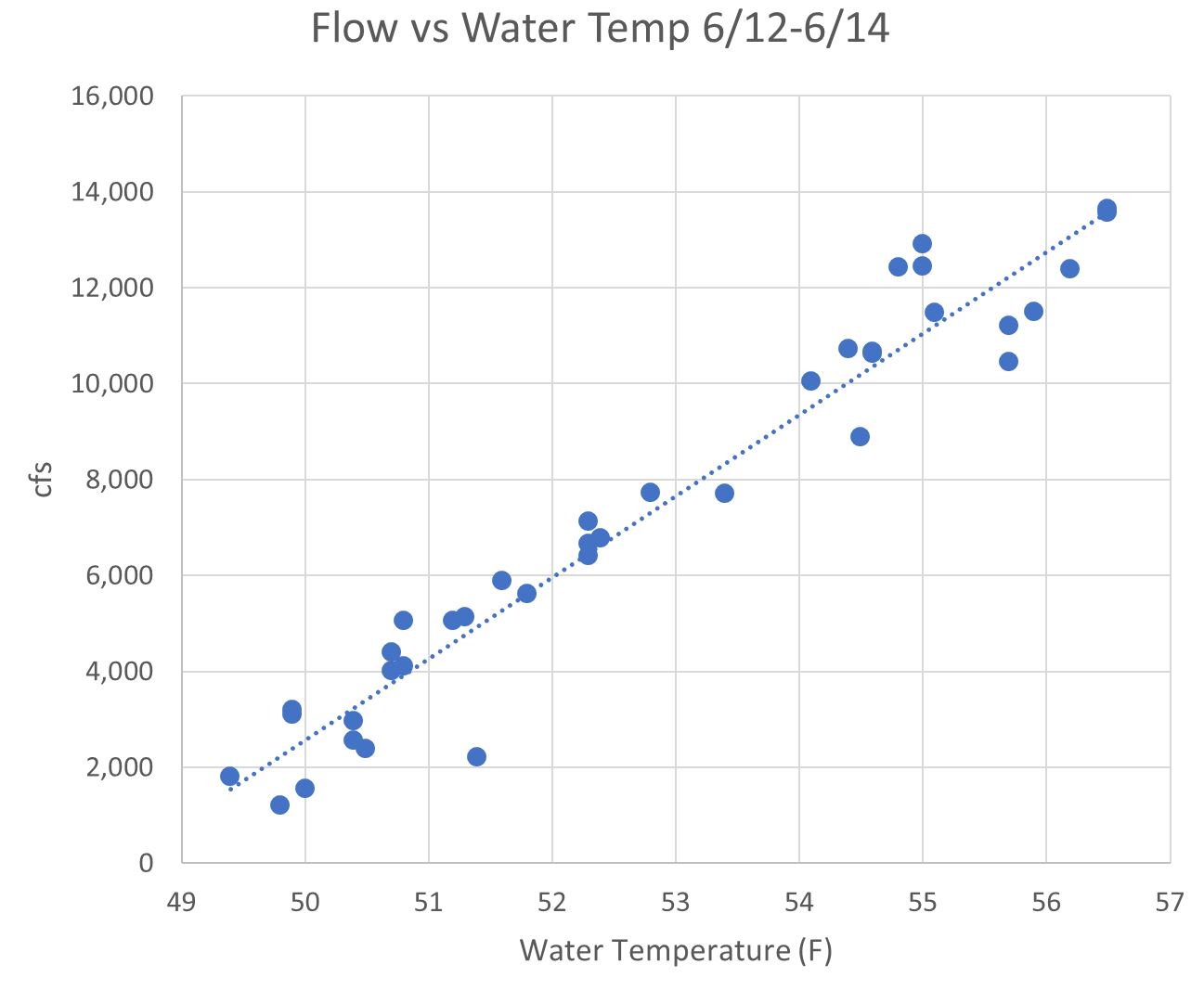

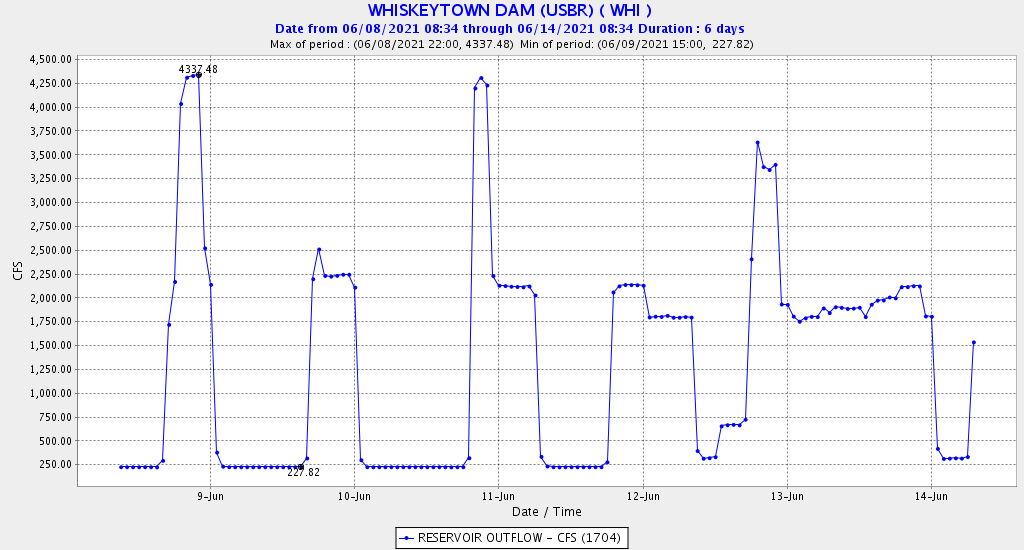

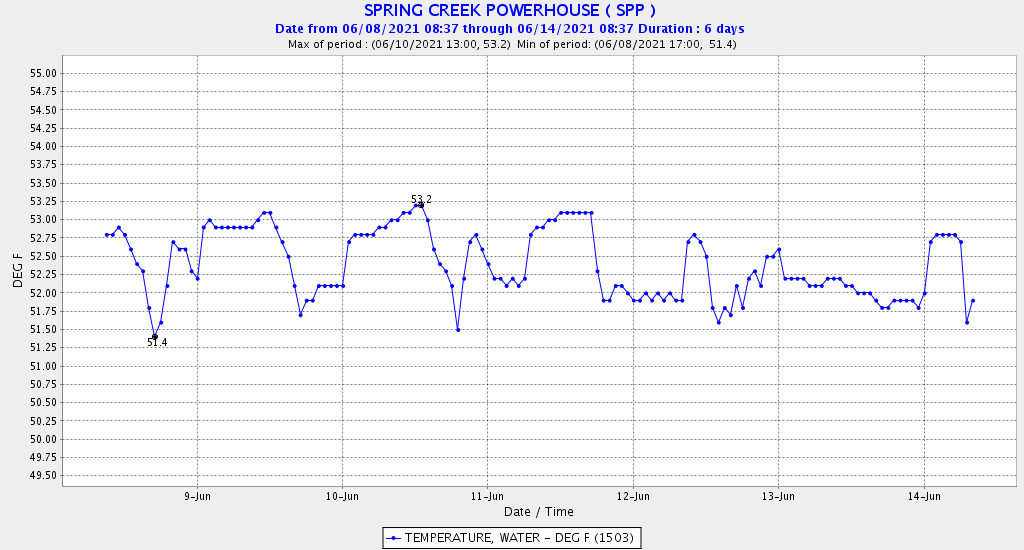

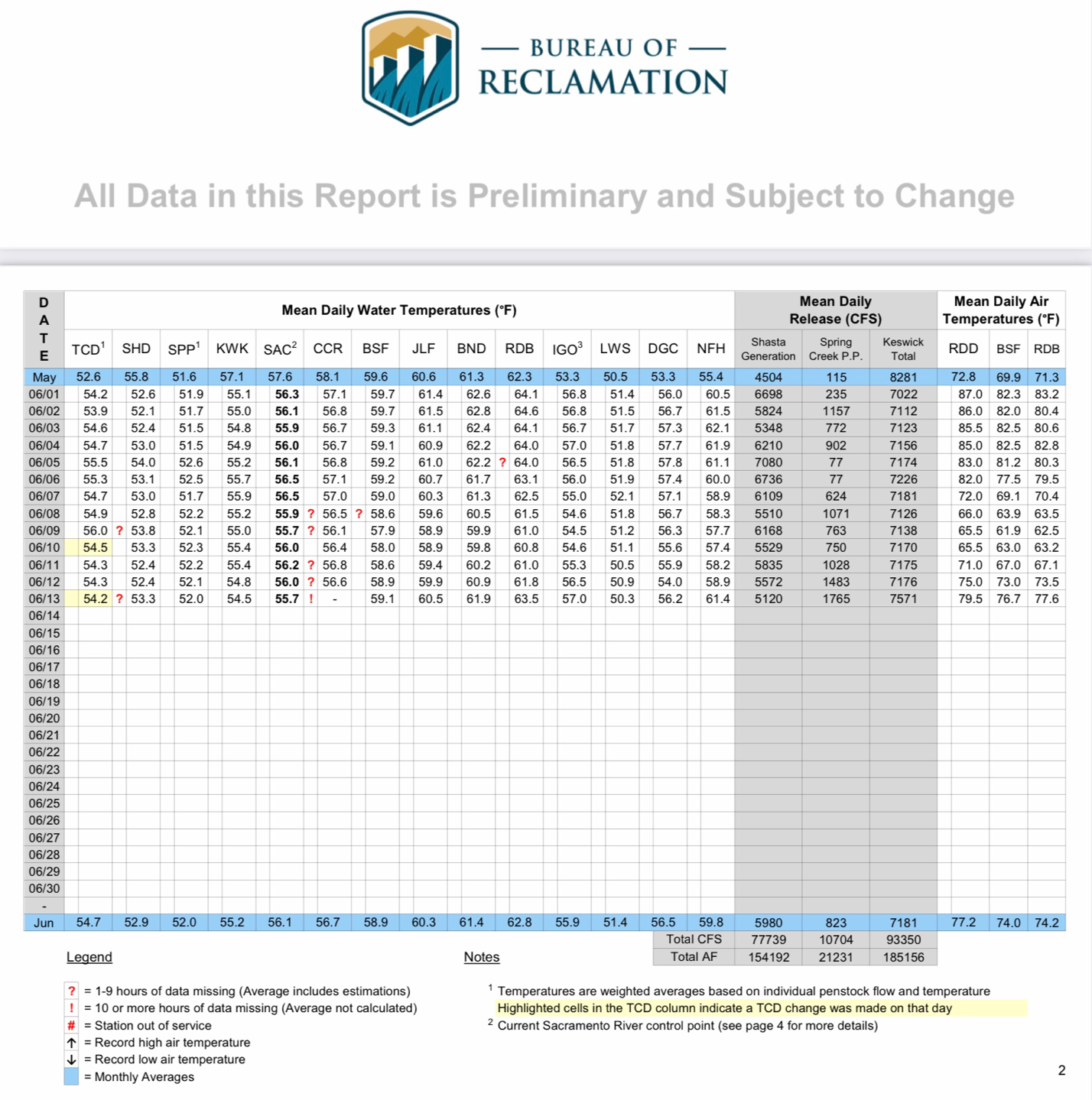

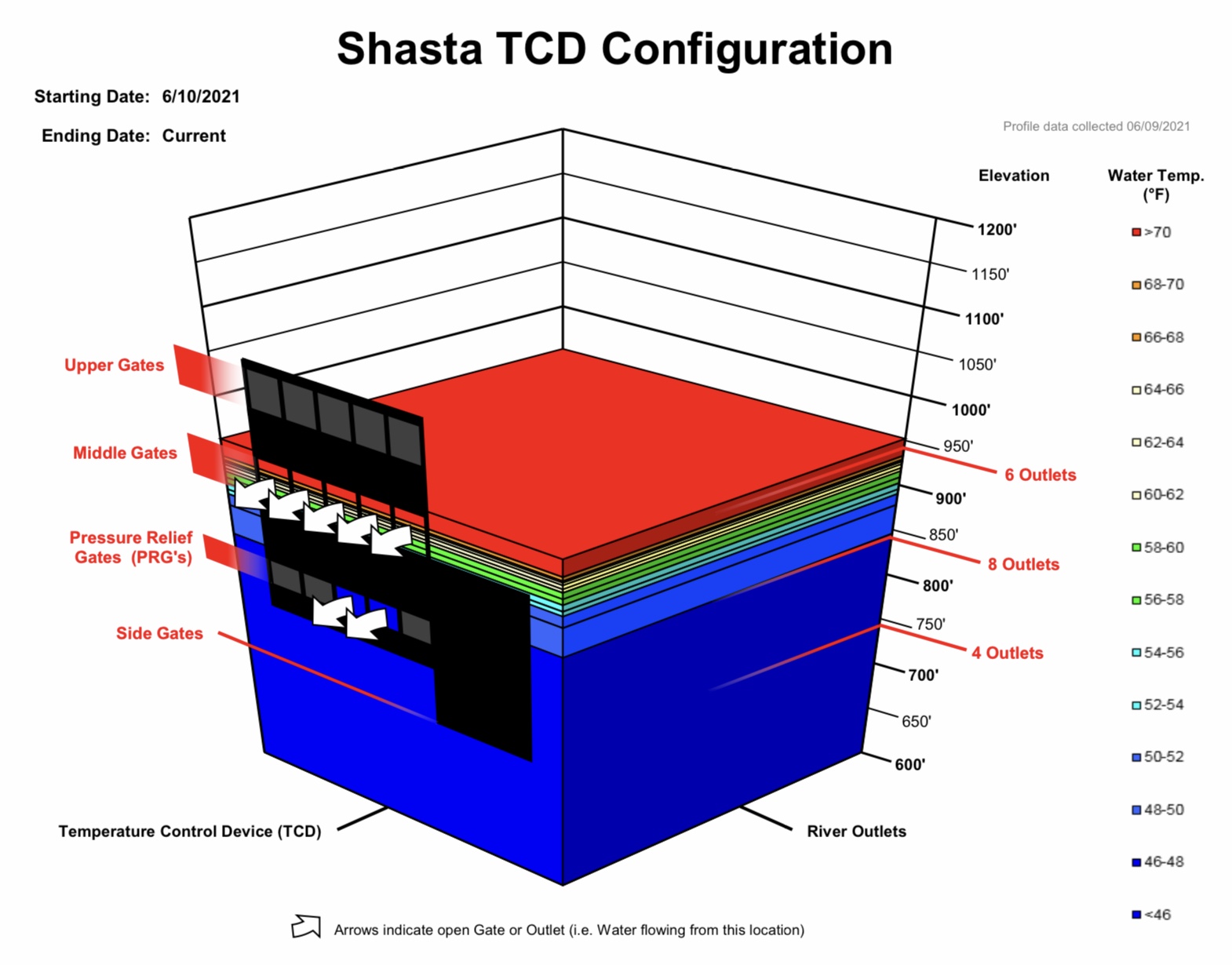

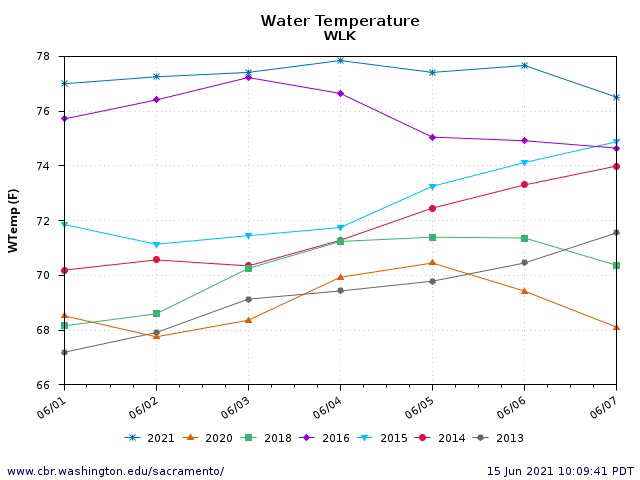

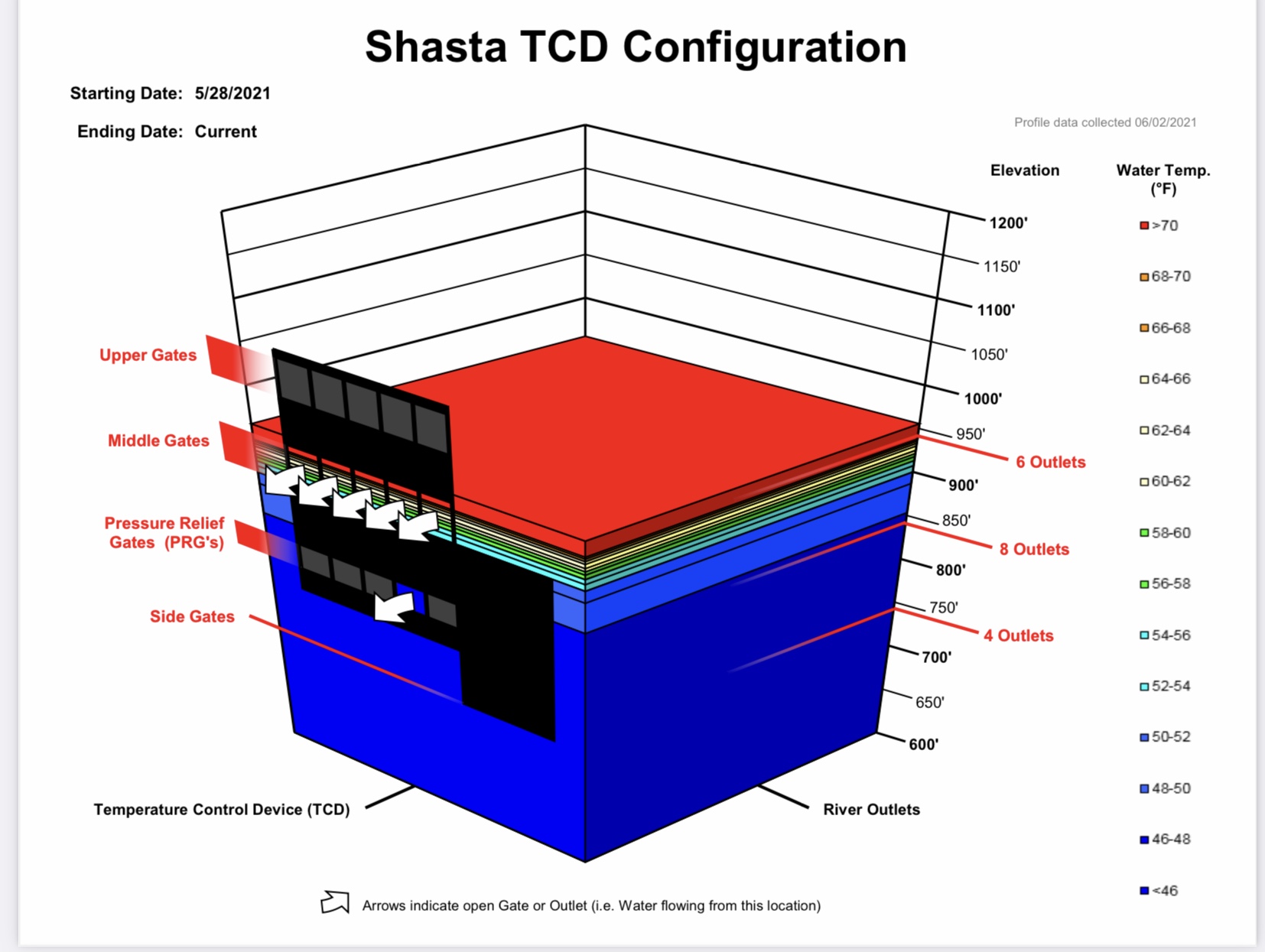

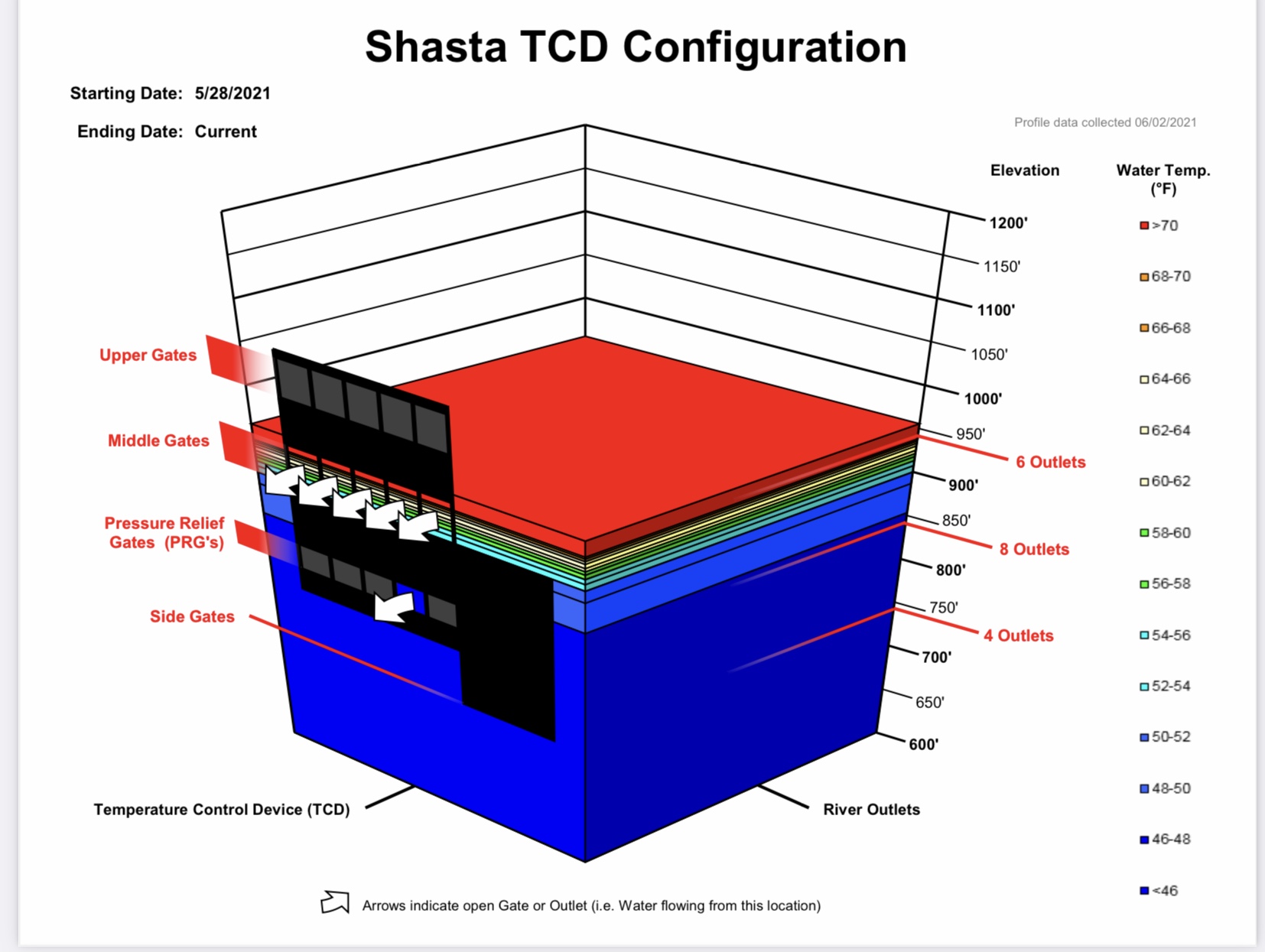

As of June 1, 2021, the Bureau of Reclamation’s summer plan for Shasta-Trinity-Keswick operation is to release 7000-8000 cfs of Shasta and Trinity water from Keswick Reservoir to the ten-mile salmon spawning reach of the upper Sacramento River near Redding. Target water temperatures are 56ºF for the Keswick release and 57ºF five miles downstream in Redding. The flow and water temperature targets are met by mixing Shasta reservoir (~6000 cfs) and Trinity releases (1000-2000 cfs via the Spring Creek powerhouse) in Keswick Reservoir. The Shasta release water temperature needs to be 54-56ºF to meet the Keswick release target temperature. This depends on the temperature of the Trinity water delivered into Keswick Reservoir through the Spring Creek Powerhouse. The water temperature of Spring Creek PH releases increases steadily over the summer, from 51-52ºF in early June to 56-57ºF later in summer. The Shasta release temperature is controlled by selecting specific outlet gate operations in Shasta Dam (Figure 8). The plan is to gradually use the Shasta cold-water pool through the summer via the pressure relief gates and to begin using side gates sometime in August as the reservoir (and cold-water-pool) volume and elevation drops.

The problem with this plan is that it leads to very poor survival (near zero) of winter-run salmon eggs in the ten-mile spawning reach downstream of Keswick Dam. It also virtually dooms reproductive survival of spring-run and fall-run salmon in the fall. The Keswick release needs to be less than 53ºF to ensure survival. Midsummer side gate use is also unreliable, often leading to loss of access to the cold-water pool.

The Alternative Temperature Management Plan (CSPA TMP) that CSPA and two other groups submitted to the State Water Board on May 23, 2021, would provide much better water temperatures from June through October. The CSPA TMP, comprised of a transmittal letter, descriptive elements and spreadsheet, proposes a release of just 5000 cfs of 52-53ºF water from Shasta Dam’s gates and minimal warmer water inputs from the Trinity. The CSPA TMP could provide a 5000 cfs release of 53-54ºF water from Keswick, with no side-gate deployment. Reclamation could also modify daily peaking power production to limit withdrawals of warm water from the surface of Shasta reservoir.

The CSPA TMP would save the salmon and save approximately 200,000 acre-feet of Shasta storage and 200,000 acre-feet of Trinity storage. After all, this is only the second year of drought. Power production from five system powerhouses would also be significantly reduced, though power generation capacity would still be available for periods of extreme power demand. Water supply deliveries would also be significantly reduced. Water saved in storage would be available for future power production and water deliveries. Therein are the trade-offs.

Summary and Conclusions

Saving the salmon is imperative because of the already poor state of salmon populations. Two of these populations have long been listed under federal and state endangered species acts. State and federal Laws and regulations require saving the salmon. Cities and agriculture will still take most of the water, if not now, then later.

Figure 1. Water storage in acre-feet in Oroville Reservoir in 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 2. Water storage in acre-feet in Folsom Reservoir in 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 3. Water storage in acre-feet in Shasta Reservoir in 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 4. Water storage in acre-feet in Trinity Reservoir in 2014, 2015, and 2021.

Figure 5. Sacramento River flow in cfs in 2014, 2015, and 2021, at the location where it leaves the Valley at Freeport near Sacramento. Note flow dropped to near 5000 cfs in early May and in June, 2021.

Figure 6. Sacramento River flow in cfs after April 1st in 2014, 2015, and 2021, at the location where it enters the Valley at Bend Bridge near Red Bluff. Note flow was higher in April and May, 2021, reflecting higher downstream demand for Shasta storage.

Figure 7. Delta outflow from the Central Valley May-July 2014, 2015, and 2021. Note sharp drop in Delta outflow at the end of May 2021, reflecting Temporary Urgent Change Petition.

Figure 8. Shasta Dam reservoir-release infrastructure, depicting operations at the beginning of June 2021. Note a combined 6000 cfs release with an overall temperature of 52-54ºF was achieved by releasing water from five upper gates and one PRG gate.