The Bureau of Reclamation’s standard fall operation of Shasta Reservoir and Keswick Reservoir dewaters the redds of fall-run Chinook salmon in the upper Sacramento River near Redding. The peak in fall-run Chinook salmon spawning is October-November. Eggs and alevin (hatched sac fry) remain buried one to two feet down in the gravel spawning bed (redd) for about three months. As I described in a November 2019 post and in prior posts, drops in flow and associated water levels cause varying degrees of redd stranding or dewatering, and the affected eggs and alevins die.

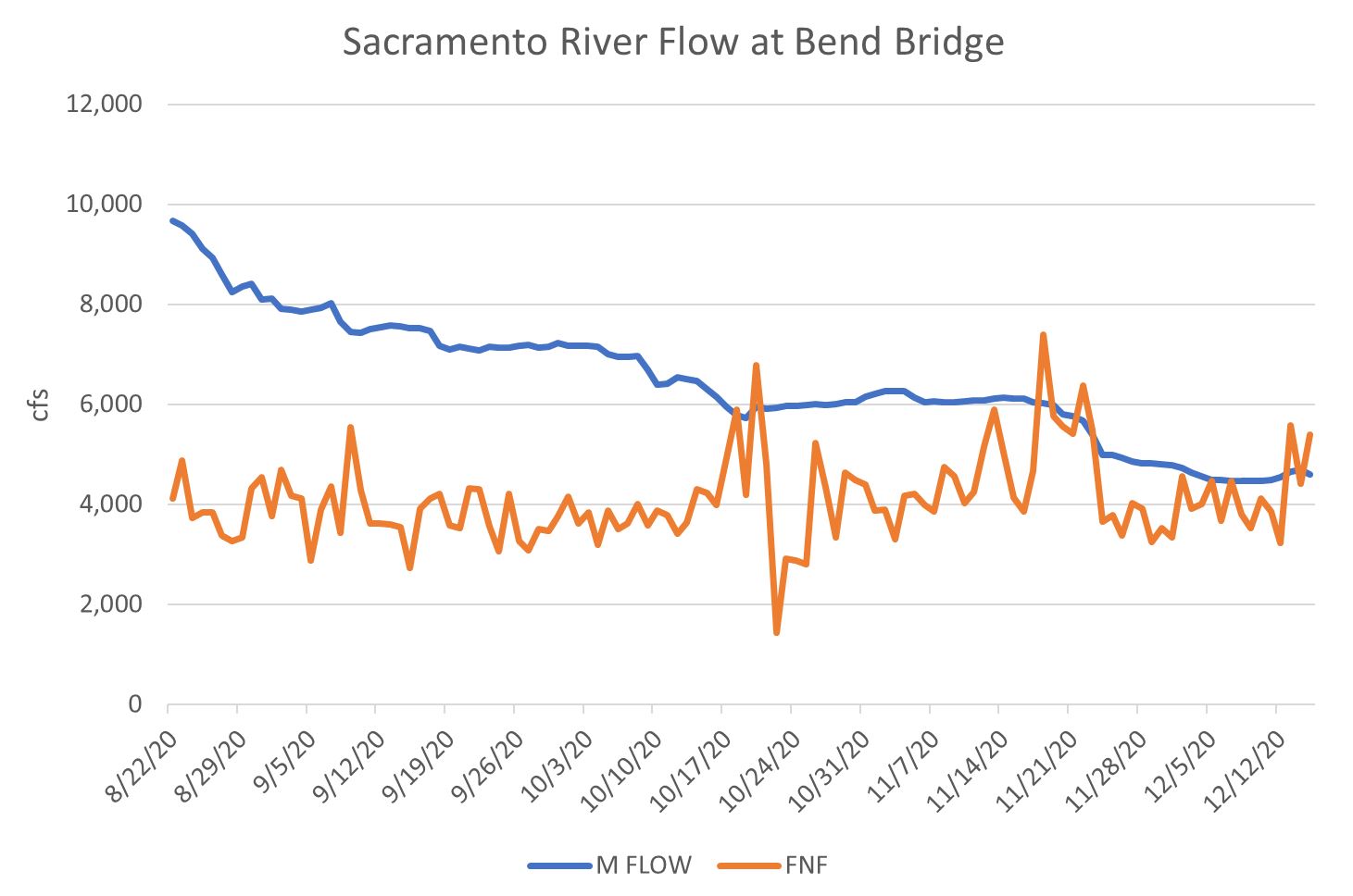

Fall-run salmon spawn from September to December, with a peak in October-November. It takes several months for eggs to hatch and fry to leave the gravel beds. Under unregulated conditions, fall-run salmon spawn in the generally stable flows of fall, and their young move toward the ocean with winter rains. The natural versus present managed flow patterns are compared in Figure 1.

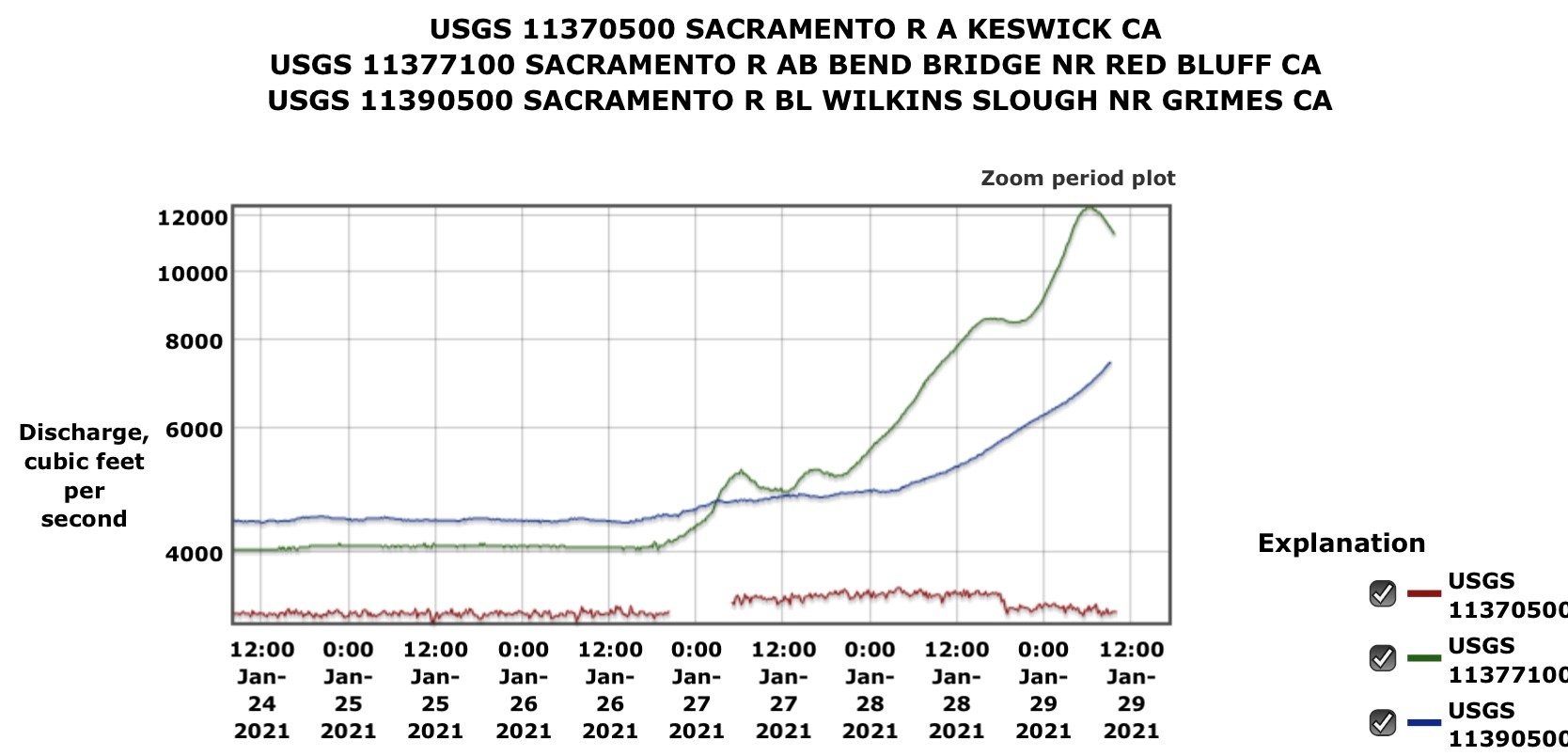

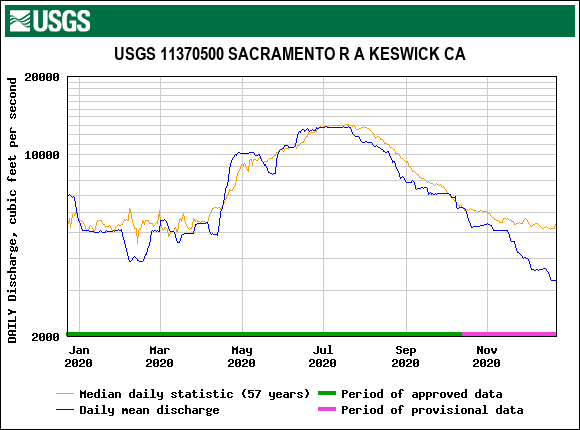

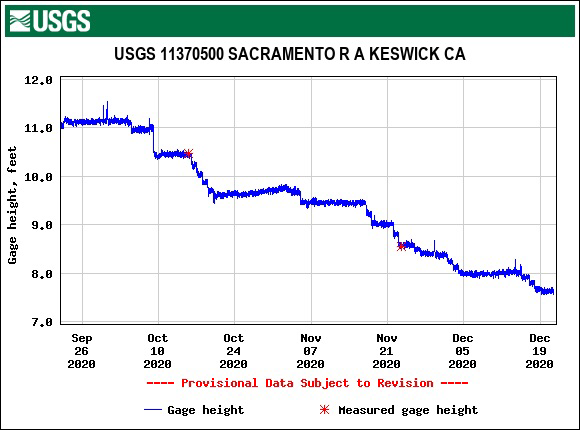

The problem has been getting worse in recent decades with the greater emphasis on water deliveries and on summer spawning conditions for winter-run salmon. Each fall, after the summer irrigation and the incubation period for winter-run Chinook salmon wind down, Reclamation reduces reservoir releases from Shasta and Keswick by 20-30%, especially in drier years like 2020 (Figure 2). Water levels in 2020 dropped about 3 ft over the fall (Figure 3), completely dewatering the earliest redds.

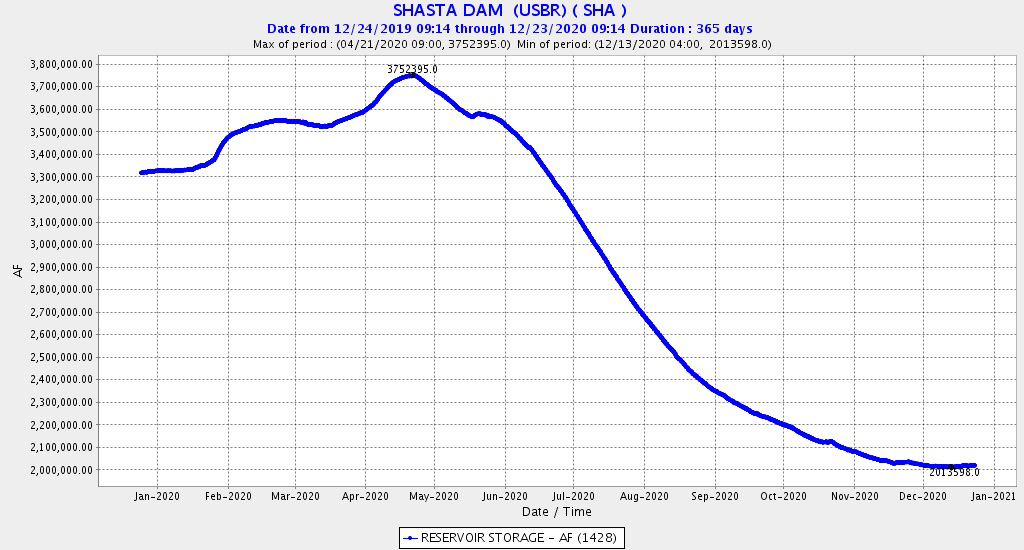

Reclamation should have averted the problem by maintaining fall releases from Shasta near 5000 cfs (Figure 3), at a cost of about 100,000 acre-ft of Shasta storage for the fall, or about 5% of Shasta dry-year minimum storage (Figure 4). The need would continue into early winter, but the effect on Shasta storage would depend on winter precipitation.

Figure 1. Managed vs full natural flow from Keswick Dam to the upper Sacramento River in fall 2020.

Figure 2. Keswick Dam water releases in 2020 and 57-year average.

Figure 3. Water levels in Sacramento River below Keswick Dam in 2020.

Figure 4. Shasta Reservoir storage in 2020. Note the reservoir had 1.3 million acre-ft of additional water stored at the beginning of the year than at the end. Water year 2019 was wet and 2020 was dry.